<Back to Index>

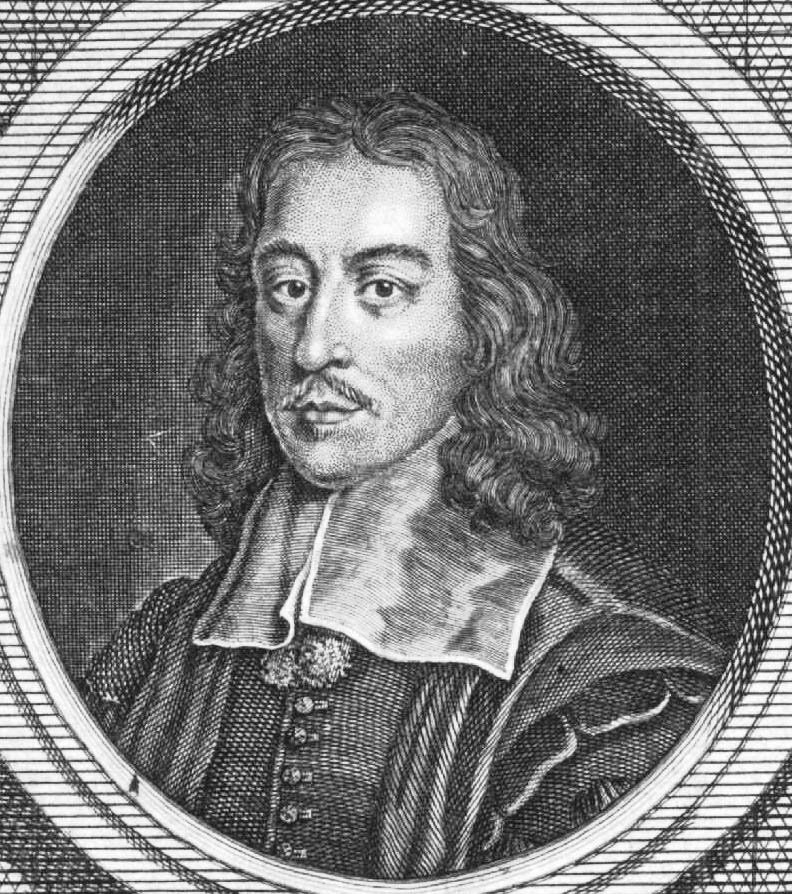

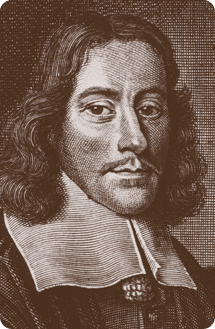

- Anatomist and Neurologist Thomas Willis, 1621

PAGE SPONSOR

Thomas Willis (27 January 1621 – 11 November 1675) was an English doctor who played an important part in the history of anatomy, neurology and psychiatry. He was a founding member of the Royal Society.

Willis was born on his parents' farm in Great Bedwyn, Wiltshire, where his father held the stewardship of the Manor. He was a kinsman of the Willys Baronets of Fen Ditton, Cambridgeshire. He graduated M.A. from Christ Church, Oxford, in 1642. In the Civil War years he was a royalist, dispossessed of the family farm at North Hinksey by Parliamentary forces. In the 1640s Willis was one of the royal physicians to Charles I of England. Less grandly, once qualified B. Med. in 1646, he began as an active physician by regularly attending the market at Abingdon.

He maintained an Anglican position; an Anglican congregation met at his lodgings in the 1650s, including John Fell, John Dolben, and Richard Allestree. Fell's father Samuel Fell had been expelled as Dean of Christ Church, in 1647; Willis married Samuel Fell's daughter Mary, and brother - in - law John Fell would later be his biographer. He employed Robert Hooke as an assistant, in the period 1656-8; this probably was another Fell family connection, since Samuel Fell knew Hooke's father in Freshwater, Isle of Wight.

One of several Oxford cliques of those interested in science grew up around Willis and Christ Church. Besides Hooke, others in the group were Nathaniel Hodges, John Locke, Richard Lower, Henry Stubbe and John Ward. (Locke went on to study with Thomas Sydenham, who would become Willis's leading rival, and who both politically and medically held some incompatible views.) In the broader Oxford scene, he was a colleague in the 'Oxford club' of experimentalists with Ralph Bathurst, Robert Boyle, William Petty, John Wilkins and Christopher Wren. Willis was on close terms with Wren's sister Susan Holder, skilled in the healing of wounds.

Willis lived on Merton Street, Oxford, from 1657 to 1667. In 1656 and 1659 he published two significant medical works, De Fermentatione and De Febribus. These were followed by the 1664 volume on the brain, which was a record of collaborative experimental work. From 1660 until his death, he was Sedleian Professor of Natural Philosophy at Oxford. At the time of the formation of the Royal Society of London, he was on the 1660 list of priority candidates, and became a Fellow in 1661. Henry Stubbe became a polemical opponent of the Society, and used his knowledge of Willis's earlier work before 1660 to belittle some of the claims made by its proponents.

Willis later worked as a physician in Westminster, London, this coming about after he treated Gilbert Sheldon in 1666. He had a successful medical practice, in which he applied both his understanding of anatomy and known remedies, attempting to integrate the two; he mixed both iatrochemical and mechanical views. According to Noga Arikha

| “ | Willis combined the physician's expert anatomical sophistication with the fluent use of an interpretive apparatus that see - sawed between novelty and tradition, Galenism and Gassendist atomism, iatrochemistry and mechanism. | ” |

Among his patients was the philosopher Anne Conway, but although he was consulted, Willis failed to relieve her headaches.

Willis is mentioned in John Aubrey's Brief Lives; their families became linked generations later through the marriage of Aubrey's distant cousin Sir John Aubrey, 6th Baronet of Llantrithyd to Martha Catherine Carter, the grand - niece of Sir William Willys, 6th Baronet of Fen Ditton.

He was a pioneer in research into the anatomy of the brain, nervous system and muscles. The "circle of Willis", a part of the brain, was his discovery.

His anatomy of the brain and nerves, as described in his Cerebri anatome of 1664, is minute and elaborate. This work coined the term neurology, and was not the result of his own personal and unaided exertions; he acknowledged his debt to Christopher Wren, who provided drawings, Thomas Millington, and his fellow anatomist Richard Lower. It abounds in new information, and presents an enormous contrast with the vaguer efforts of his predecessors.

In 1667 he published Pathologicae cerebri, et nervosi generis specimen, an important work on the pathology and neurophysiology of the brain. In it he developed a new theory of the cause of epilepsy and other convulsive diseases, and contributed to the development of psychiatry. In 1672 he published the earliest English work on medical psychology, 'Two Discourses concerning The Soul of Brutes, Which is that of the Vital and Sensitive of Man'.

Willis was the first to number the cranial nerves in the order in which they are now usually enumerated by anatomists. His observation of the connexion of the eighth pair with the slender nerve which issues from the beginning of the spinal cord is known to all. He remarked the parallel lines of the mesolobe (corpus callosum), afterwards minutely described by Félix Vicq - d'Azyr. He seems to have recognized the communication of the convoluted surface of the brain and that between the lateral cavities beneath the fornix. He described the corpora striata and optic thalami; the four orbicular eminences, with the bridge, which he first named annular protuberance; and the white mammillary eminences, behind the infundibulum. In the cerebellum he remarks the arborescent arrangement of the white and grey matter, and gives a good account of the internal carotids, and the communications which they make with the branches of the basilar artery.

He coined the term mellitus in diabetes mellitus. An old name for the condition is "Willis's disease". He observed what had been known for many centuries elsewhere, that the urine is sweet in patients (glycosuria). His observations on diabetes formed a chapter of Pharmaceutice rationalis (1674). Further research came from Johann Conrad Brunner, who had met Willis in London.

Willis's work gained currency in France through the writings of Daniel Duncan. The philosopher Richard Cumberland quickly applied the findings on brain anatomy to argue a case against Thomas Hobbes's view of the primacy of the passions.