<Back to Index>

- King of the Visigoths Alaric I, 370

PAGE SPONSOR

Alaric I (Alareiks in the original Gothic) was likely born about 370 on an island named Peuce (the Fir) at the mouth of the Danube in present day Romania. King of the Visigoths from 395 – 410, Alaric was the first Germanic leader to take the city of Rome. Having originally desired to settle his people in the Roman Empire, he finally sacked the city, marking the decline of imperial power in the west.

Alaric was well born, his father kindred to the Balti, a tribe competing with the Amali among Gothic fighters. He belonged to the western Gothic branch, the Visigoths. At the time of his birth, the Visigoths dwelt in Bulgaria, having fled beyond the wide estuary marshes of the Danube to its southern shore so as not to be followed by their foes from the steppe, the Huns.

There is evidence, however, as suggested by Peter Heather, that the

Huns were not near the Danube until closer to the 5th century. What is certain

is that the Visigoths' westward migration occurred in response to the

threat posed by the Huns. Heather asserts, "Mysterious as the Huns'

origins and animating forces may remain, there is no doubt at all that

they were behind the strategic revolution that brought the Goths to the

Danube in the summer of 376." Moreover, concerning the Huns displacement

of the Goths, ancient historian Ammianus Marcellinus concluded,

"The seed - bed and origin of all this destruction and of the various

calamities inflicted by the wrath of Mars, which raged everywhere with

extraordinary fury, I find to be this: the people of the Huns." Ammianus

Marcellinus was right - the Huns were behind the military revolution

that had brought the Tervingi and Greuthungi to the Danube sometime in

the late summer or autumn of 376. It now presented Emperor Valens with a huge dilemma - tens of thousands of displaced Goths had suddenly arrived on his borders requesting asylum.

During the fourth century, the Roman emperors commonly employed foederati: Germanic irregular troops under Roman command, but organized by tribal structures. To spare the provincial populations from excessive taxation and to save money, emperors began to employ units recruited from Germanic tribes. The rich balked at furnishing recruits from their own estates in the numbers needed for the empire's defense and ordinary folk were reluctant to serve. Instead, the rich paid a special tax to fund the hiring of mercenaries. Moreover, the emperors — ever fearful that a brilliantly successful general of Roman extraction might be proclaimed Augustus by his followers — preferred that high military command should be in the hands of one to whom such an accession of dignity was impossible. The largest of these contingents was that of the Goths, who in 382, had been allowed to settle within the imperial boundaries, keeping a large degree of autonomy.

In 394, Alaric served as a leader of foederati under Theodosius I in the campaign which crushed the usurper Eugenius. As the Battle of the Frigidus, which terminated this campaign, was fought at the passes of the Julian Alps, Alaric probably learned the weakness of Italy's natural defences on its northeastern frontier at the head of the Adriatic.

Theodosius died in 395, leaving the empire to be divided between his two sons Arcadius and Honorius, the former taking the eastern and the latter, the western portion of the empire. Arcadius showed little interest in ruling, leaving most of the actual power to his Praetorian Prefect Rufinus. Honorius was still a minor; as his guardian, Theodosius had appointed the magister militum Stilicho. Stilicho also claimed to be the guardian of Arcadius, causing much rivalry between the western and eastern courts.

According to Edward Gibbon in

The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, during the

shifting of offices that took place at the beginning of the new reigns,

Alaric apparently hoped he would be promoted from a mere commander to

the rank of general in one of the regular armies. He was denied the

promotion, however. Among the Visigoths settled in Lower Moesia,

the situation was ripe for rebellion. They had suffered

disproportionately great losses at Frigidus. And according to rumour,

exposing the Visigoths in battle was a convenient way of weakening the

Gothic tribes. This, combined with their post - battle rewards, prompted

them to raise Alaric "on a shield" and proclaim him king; according to Jordanes (a

Gothic historian of varying importance, depending upon who is asked),

both the new king and his people decided "rather to seek new kingdoms by

their own work, than to slumber in peaceful subjection to the rule of

others."

Alaric struck first at the eastern empire. He marched to the neighborhood of Constantinople but, finding himself unable to undertake a siege, retraced his steps westward and then marched southward through Thessaly and the unguarded pass of Thermopylae into Greece.

The armies of the eastern empire were occupied with Hunnic incursions in Asia Minor and Syria. Instead, Rufinus attempted to negotiate with Alaric in person, which only aroused suspicions in Constantinople that Rufinius was in league with the Goths. Stilicho now marched east against Alaric. According to Claudian, Stilicho was in a position to destroy the Goths when he was ordered by Arcadius to leave Illyricum. Soon after, Rufinus' own soldiers hacked him to death. Power in Constantinople now passed to the eunuch Chamberlain Eutropius.

Rufinus' death and Stilicho's departure gave free rein to Alaric's movements; he ravaged Attica but spared Athens, which capitulated at once to the conqueror. In 396, he wiped out the last remnants of the Mysteries at Eleusis in Attica, ending a tradition of esoteric religious ceremonies that had lasted since the Bronze Age. Then he penetrated into the Peloponnesus and captured its most famous cities — Corinth, Argos, and Sparta — selling many of their inhabitants into slavery.

Here,

however, his victorious career suffered a serious setback. In 397,

Stilicho crossed the sea to Greece and succeeded in trapping the Goths

in the mountains of Pholoe, on the borders of Elis and Arcadia in

the peninsula. From there Alaric escaped with difficulty, and not

without some suspicion of connivance by Stilicho, who supposedly had

again received orders to depart. Alaric then crossed the Gulf of Corinth and marched with the plunder of Greece northward to Epirus. Here his rampage continued until the eastern government appointed him magister militum per Illyricum, giving him the Roman command he had desired, as well as the authority to resupply his men from the imperial arsenals.

It was probably in 401 that Alaric made his first invasion of Italy. Supernatural influences were not lacking to urge him to this great enterprise. Some lines of the Roman poet Claudian inform us that he heard a voice proceeding from a sacred grove, "Break off all delays, Alaric. This very year thou shalt force the Alpine barrier of Italy; thou shalt penetrate to the city." But the prophecy was not to be fulfilled at this time. After spreading desolation through North Italy and striking terror into the citizens of Rome, Alaric was met by Stilicho at Pollentia, today in Piedmont. The battle which followed on April 6, 402 (coinciding with Easter), was a victory for Rome, though a costly one. But it effectively halted the Goths' progress.

Stilicho's enemies later reproached him for having gained his victory by taking impious advantage of the great Christian festival. Alaric, too, was a Christian, though an Arian, not Orthodox. He had trusted to the sanctity of Easter for immunity from attack.

Alaric's wife was reportedly taken prisoner after this battle; it is not unreasonable to suppose that he and his troops were hampered by the presence of large numbers of women and children, which gave his invasion of Italy the character of a human migration.

After another defeat before Verona,

Alaric left Italy, probably in 403. He had not "penetrated to the city"

but his invasion of Italy had produced important results. It caused the

imperial residence to be transferred from Milan to Ravenna, and necessitated the withdrawal of Legio XX Valeria Victrix from Britain.

Alaric became the friend and ally of his late opponent, Stilicho. By 407, the estrangement between the eastern and western courts had become so bitter that it threatened civil war. Stilicho actually proposed using Alaric's troops to enforce Honorius' claim to the prefecture of Illyricum. The death of Arcadius in May 408 caused milder counsel to prevail in the western court, but Alaric, who had actually entered Epirus, demanded in a somewhat threatening manner that if he were thus suddenly requested to desist from war, he should be paid handsomely for what modern language would call the "expenses of mobilization". The sum which he named was a large one, 4,000 pounds of gold. Under strong pressure from Stilicho, the Roman senate consented to promise its payment.

But three months later, Stilicho and the chief ministers of his party were treacherously slain on Honorius' orders. In the unrest that followed throughout Italy, the wives and children of the foederati were slain. Consequently, these 30,000 men flocked to Alaric's camp, clamouring to be led against their cowardly enemies. He accordingly led them across the Julian Alps and, in September 408, stood before the walls of Rome (now with no capable general like Stilicho as a defender) and began a strict blockade.

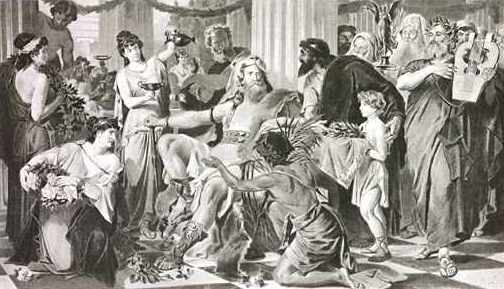

No blood was shed this time; Alaric relied on hunger as his most powerful weapon. When the ambassadors of the Senate, entreating for peace, tried to intimidate him with hints of what the despairing citizens might accomplish, he laughed and gave his celebrated answer: "The thicker the hay, the easier mowed!" After much bargaining, the famine stricken citizens agreed to pay a ransom of 5,000 pounds of gold, 30,000 pounds of silver, 4,000 silken tunics, 3,000 hides dyed scarlet, and 3,000 pounds of pepper. Thus ended Alaric's first siege of Rome.

Throughout

his career, Alaric's primary goal was not to undermine the empire, but

to secure for himself a regular and recognized position within the

empire's borders. His demands were certainly grand — the concession of a

block of territory 200 miles long by 150 wide between the Danube

and the Gulf of Venice (to be held probably on some terms of nominal

dependence on the empire) and the title of commander - in - chief of the

imperial army. Immense as his terms were, the emperor would have been

well advised to grant them. Honorius, however, refused to see beyond his

own safety, guaranteed by the dikes and marshes of Ravenna. As all

attempts to conduct a satisfactory negotiation with this emperor failed,

Alaric, after instituting a second siege and blockade of Rome in 409,

came to terms with the senate. With their consent, he set up a rival

emperor, the prefect of the city, a Greek named Priscus Attalus.

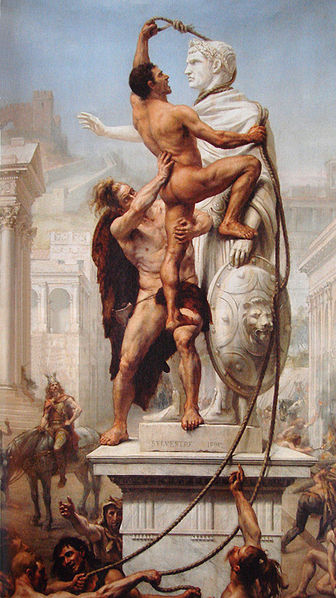

Alaric cashiered his ineffectual puppet emperor after eleven months and again tried to reopen negotiations with Honorius. These negotiations might have succeeded had it not been for the malignant influence of another Goth, Sarus, an Amali, and therefore hereditary enemy of Alaric and his house. Alaric, again outwitted by an enemy's machinations, marched southward and in deadly earnest, began his third siege of Rome. Apparently, defence was impossible; there are hints, not well substantiated, of treachery; surprise is a more likely explanation. However, this may be — for our information at this point of the story is meagre — on August 24 410, Alaric and his Visigoths burst in by the Porta Salaria on the northeast of the city. Rome, for so long victorious against its enemies, was now at the mercy of its foreign conquerors.

The contemporary ecclesiastics recorded

with wonder many instances of the Visigoths' clemency: Christian

churches saved from ravage; protection granted to vast multitudes both

of pagans and Christians who took refuge therein; vessels of gold and

silver which were found in a private dwelling, spared because they

"belonged to St. Peter"; at least one case in which a beautiful Roman

matron appealed, not in vain, to the better feelings of the Gothic

soldier who attempted her dishonor. But even these exceptional instances

show that Rome was not entirely spared the horrors which usually

accompany the storming of a besieged city. Nonetheless, the written

sources do not mention damages wrought by fire, save the Gardens of Sallust,

which were situated close to the gate by which the Goths had made their

entrance; nor is there any reason to attribute any extensive

destruction of the buildings of the city to Alaric and his followers.

The Basilica Aemilia in the Roman Forum did

burn down, which perhaps can be attributed to Alaric: the

archaeological evidence was provided by coins dating from 410 found

melted in the floor. The pagan emperors' tombs of the Mausoleum of Augustus and Castel Sant' Angelo were rifled and the ashes scattered.

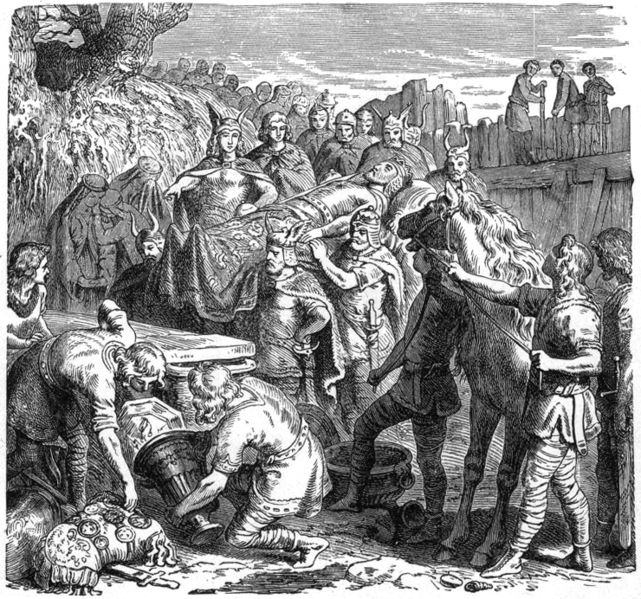

Alaric, having penetrated the city, marched southwards into Calabria. He desired to invade Africa, which, thanks to its grain, had become the key to holding Italy. But a storm battered his ships into pieces and many of his soldiers drowned. Alaric died soon after in Cosenza, probably of fever, at the age of about forty (assuming again, a birth around 370 AD), and his body was, according to legend, buried under the riverbed of the Busento. The stream was temporarily turned aside from its course while the grave was dug wherein the Gothic chief and some of his most precious spoils were interred. When the work was finished, the river was turned back into its usual channel and the captives by whose hands the labor had been accomplished were put to death that none might learn their secret.

Alaric was succeeded in the command of the Gothic army by his brother - in - law,Ataulf, who married Honorius' sister Galla Placidia three years later.

The chief authorities on the career of Alaric are: the historian Orosius and the poet Claudian, both contemporary, neither disinterested; Zosimus, a historian who lived probably about half a century after Alaric's death; and Jordanes, a Goth who wrote the history of his nation in 551, basing his work on The Trojan War. The legend of Alaric's burial in the Buzita River comes from Jordanes.