<Back to Index>

- Mughal Emperor of India Bahadur Shah II, 1775

- Philosopher and Freedom Fighter Fazl-e-Haq Khairabadi, 1797

- Imam of Nizari Ismailism Aga Khan I, 1804

PAGE SPONSOR

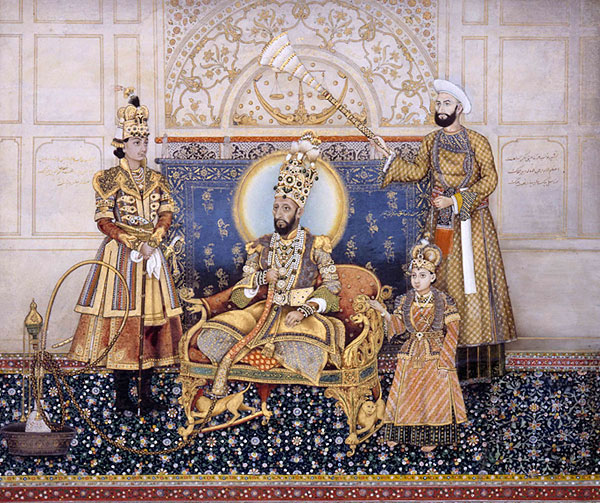

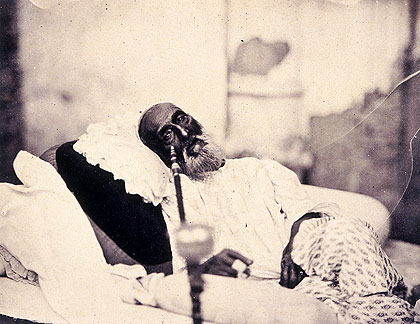

His Royal Highness Abu Zafar Sirajuddin Muhammad Bahadur Shah Zafar (Urdu: ابو ظفر سِراجُ الْدین محمد بُہادر شاہ ظفر), also known as Bahadur Shah or Bahadur Shah II (Urdu:بہادر شاہ دوم) (October 1775 – 7 November 1862) was the last of the Mughal emperors in India, as well as the last ruler of the Timurid Dynasty. He was the son of Akbar Shah II and Lalbai, who was a Hindu Rajput. He became the Mughal Emperor upon his father's death on 28 September 1837. Zafar (Urdu: ظفر), meaning “victory” was his nom de plume (takhallus) as an Urdu poet and was popularly also known as Bahadur Shah Zafar .

Zafar's father, Akbar Shah II, ruled over a rapidly disintegrating empire between 1806 to 1837. It was during his time that the East India Company dispensed with the illusion of ruling in the name of the Mughal monarch and removed his name from the Persian texts that appeared on the coins struck by the company in the areas under their control.

Bahadur

Shah Zafar who succeeded him was not Akbar Shah Saani’s choice as his

successor. Akbar Shah was, in fact, under great pressure by one of his

queens, Mumtaz Begum to declare her son Mirza Jahangir as the successor.

Akbar Shah would have probably accepted this demand but Mirza Jahangir

had fallen afoul of the British and they would have none of this.

Bahadur Shah Zafar presided over a Mughal empire that barely extended beyond Delhi's Red Fort. The British were the dominant political and military power in 19th century India. Outside British India, hundreds of kingdoms and principalities, from the large to the small, fragmented the land. The emperor in Delhi was paid some respect by the British and allowed a pension, the authority to collect some taxes, and to maintain a small military force in Delhi, but he posed no threat to any power in India. Bahadur Shah II himself did not take an interest in statecraft or possess any imperial ambitions. After the Sepoy Mutiny the British Administration exiled him from Delhi. This has been well documented in William Dalrymple's book The Last Mughal and is well corroborated from many other archival sources.

Bahadur Shah Zafar was a noted Urdu poet. He wrote a large number of Urdu ghazals. While some part of his opus was lost or destroyed during the Indian Rebellion of 1857 - 1858, a large collection did survive, and was later compiled into the Kulliyyat - i - Zafar. The

court that he maintained, although somewhat decadent and arguably

pretentious for someone who was effectively a pensioner of the British East India Company, was home to several Urdu writers of high standing, including Ghalib, Dagh, Mumin, and Zauq.

“ As long as there remains the scent of faith in the hearts of our Ghazis, so long shall the sword of Hindustan flash before the throne of London ”

Emperor Bahadur Shah is seen as a freedom fighter (he was Commander - In - Chief of the mutiny army), fighting for India's independence from the British. As the last ruling member of the imperial Timurid Dynasty he was surprisingly composed and calm when Major Hodson presented decapitated heads of his own sons to him as Nowruz gifts. He is famously remembered to have said.

| “ | Thanks to Allah, the descendents of Timur always come in front of their fathers in this way. | ” |

On May 11th the regiments that had rebelled at Lucknow the previous day reached Delhi and asked for a formal audience. On the 12th, it was granted, and he was petitioned. While it is questionable that he did so unforced, and eyewitness described how the mutineers treated him with contempt, he nevertheless gave his assent issuing the following decree, a Shahi Firman (King's decree), on May 12, 1857:

To all the Hindus and Muslims of India, taking my duty by the people into consideration at this hour, I have decided to stand by my people. Whoever shows cowardice at this delicate hour, or whoever in innocence will help the cunning English, believing in their promises, he would stand disillusioned very soon. He should remember that the English will pay him for his faithfulness to them in the same manner as they have paid the rulers of Oudh. It is the imperative duty of Hindus and Mussalmans (Muslims) to join the revolt against the English. They should work and be guided by their leaders in their towns and should take steps to restore order in the country. It is the bounden duty of all people that they should, as far as possible, copy out this Firman and display it at all important places in the towns. But before doing so, they should get themselves armed and declare war on the English.

Bahadur Shah Zafar was a devout Sufi. Zafar was himself regarded as a Sufi Pir and used to accept murids or pupils. The loyalist newspaper Delhi Urdu Akhbaar once called him one of the leading saints of the age, approved of by the divine court. Prior to his accession, in his youth he made it a point to live and look like a poor scholar and dervish, in stark contrast to his three well dressed dandy brothers, Mirza Jahangir, Salim and Babur. In 1828, when Zafar was 53 and a decade before he succeeded the throne, Major Archer reported, "Zafar is a man of spare figure and stature, plainly apparelled, almost approaching to meanness. His appearance is that of an indigent munshi or teacher of languages".

As a poet and dervish, Zafar imbibed the highest subtleties of mystical Sufi teachings. At the same time, he was deeply susceptible to the magical and superstitious side of Orthodox Sufism. Like many of his followers, he believed that his position as both a Sufi pir and emperor gave him tangible spiritual powers. In an incident in which one of his followers was bitten by a snake, Zafar attempted to cure him by sending a "seal of Bezoar" (a stone antidote to poison) and some water on which he had breathed, and giving it to the man to drink.

The emperor also had a staunch belief in ta'aviz or charms, especially as a palliative for his constant complaint of piles, or to ward off evil spells. During one period of illness, he gathered a group of Sufi pirs and told them that several of his wives suspected that some party or the other had cast a spell over him. Therefore, he requested them to take some steps to remedy this so as to remove all apprehension on this account. They replied that they would write off some charms for him. They were to be mixed in water which when drunk would protect him from the evil eye. A coterie of pirs, miracle workers and Hindu astrologers were in constant attendance to the emperor. On their advice, he regularly sacrificed buffaloes and camels, buried eggs and arrested alleged black magicians, in addition to wearing a special ring that cured indigestion. On their advice, he also regularly donated cows to the poor, elephants to the sufi shrines and a horse to the khadims or clergy of Jama Masjid.

Zafar consciously saw his role as a protector of his Hindu subjects, and a

moderator of extreme Muslim demands and the intense puritanism of many of the Orthodox Muslim sheikhs of the Ulema. In one of his verses, Zafar explicitly stated that both Hinduism and Islam shared

the same essence. This syncretic philosophy was implemented by his

court which came to cherish and embody a multicultural composite

Hindu - Islamic Mughal culture. For instance, the Hindu elite used to

frequently visit the dargah or tomb of the great Sufi pir, Nizam - ud - din Auliya. They could quote Hafiz and

were very fond of Persian poetry. Their children, especially those

belonging to the administrative Khatri and Kayasth castes studied under

maulvis and attended the more liberal madrasas,

bringing food offerings for their teachers on Hindu festivals. On the

other hand, the emperor's Muslim subjects emulated him in honoring the

Hindu holy men, while many in court, including Zafar himself, followed

the old Mughal custom, originally borrowed from high class Hindus, of

only drinking the water from the Ganges.

Zafar and his court used to celebrate Hindu festivals. During the spring festival of Holi, he would spray his courtiers, wives and concubines with different colored paints, initiating the celebrations by bathing in the water of seven wells. The autumn Hindu festival of Dusshera was celebrated in the palace by the distribution of nazrs or presents to Zafar's Hindu officers and the coloring of the horses in the royal stud. In the evening, Zafar would then watch the Ram Lila processions annually celebrated in Delhi with the burning of giant effigies of Ravana and his brothers. He even went to the extent of demanding that the route of the procession be changed so that it would skirt the entire flank of the palace, allowing it to be enjoyed in all its glory. On Diwali, Zafar would weigh himself against seven kinds of grain, gold, coral, etc., and directed their distribution among the city's poor.

He

was reputedly known to have profound sensitivities to the feelings of

his Hindu subjects. One evening, when Zafar was riding out across the

river for an airing, a Hindu waited on the king and disclosed his wish

to become a Muslim. Hakim Ahsanullah Khan, Zafar's prime minister flatly

denied this request and the emperor had him removed from his presence.

During the Phulwalon ki Sair or Flower sellers fair held annually at the ancient Jog Maya Temple and the Sufi dargah of Qutb Sahib, Qutbuddin Bakhtiar Kaki in Mehrauli, Zafar declared that he would not accompany the pankah into the shrine as he could not accompany it into the temple.

Closely woven into the history of the last remains of Mughal rule is the history of Zafar Mahal in Mehrauli, a locality of Delhi. Zafar Mahal was originally built by Akbar II, but it was his son, Bahadur Shah Zafar, who constructed the gateway and added to the palace in the mid 19th century. Mehrauli was then a popular venue for hunting parties, picnics and jaunts, and the dargah was an added attraction. The emperor visited often with his retinue - and stayed in royal style at Zafar Mahal. Another interesting feature of Zafar Mahal is that it literally spans centuries. A plastered dome near the gate is probably 15th century; other sections are relatively newer and show definite signs of Western influences. There is, for instance, a fireplace in one of the walls that stands near the Moti Masjid. And the staircase to the balcony is a wide one with low steps - very unlike the steep, narrow staircases of most Indian Islamic architecture.

The balcony, with its 'jharokha’ windows, is where the emperor and his family could look out over the road. In Bahadur Shah’s time, the main Mehrauli - Gurgaon road passed in front of Zafar Mahal, and all passersby were expected to dismount as a sign of respect for the emperor. When the British refused to comply, Bahadur Shah solved the problem creatively - he bought the surrounding land and diverted the road so that it would pass well away from Zafar Mahal! The Phool Walon Ki Sair gradually turned into a major three day celebration during the time when Bahadur Shah Zafar, son and successor to Akbar Shah Saani ruled from Delhi.

Zafar used to move his court to a building adjacent to the Shrine of Khwaja Bakhtiyar Kaki and stayed at Mehrauli for a week during the celebrations. The building where he stayed during the period was originally built by his father and Zafar added an impressive gate and a Baaraadari to the structure and renamed it Zafar Mahal.

The celebrations spread out in different parts of Mehrauli with the Jahaz Mahal, (a Lodhi period structure, that was once in the middle of the Hauz - e - Shamsi but is now at one end of the much depleted Hauz, becoming a center where Qawwali mehfils would be organized while the Jharna, built by Firoz Shah Tughlaq and later added to by Akbar Shah II became a place where the women of the court relaxed.

As the Indian rebellion of 1857 spread, Sepoy regiments seized Delhi. Seeking a figure that could unite all Indians, Hindu and Muslim alike, most rebelling Indian kings and the Indian regiments accepted Zafar as the Emperor of India, under whom the smaller Indian kingdoms would unite until the British were defeated. Zafar was the least threatening and least ambitious of monarchs, and the legacy of the Mughal Empire was more acceptable as a uniting force to most allied kings than the domination of any other Indian kingdom.

When the victory of the British became certain, Zafar took refuge at Humayun's Tomb, in an area that was then at the outskirts of Delhi, and hid there. British forces led by Major William Hodson surrounded

the tomb and compelled his surrender on 20 September 1857. The next day

Hodson shot his sons Mirza Mughal, Mirza Khizr Sultan, and grandson

Mirza Abu Bakr under his own authority at the Khooni Darwaza (the bloody gate) near Delhi Gate. On hearing the news Zafar reacted with shocked silence while his wife Zeenat Mahal was content as she believed her son was now Zafar's heir.

Numerous male members of his family were killed by British forces, who imprisoned or exiled the surviving members of the Mughal dynasty. After a show trial, Zafar himself was exiled to Rangoon, Burma (now Yangon, Union of Myanmar) in 1858 along with his wife Zeenat Mahal and some of the remaining members of the family. His departure as Emperor marked the end of more than three centuries of Mughal rule in India.

Bahadur Shah died in exile on 7 November 1862. He was buried near the Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon, at the site that later became known as Bahadur Shah Zafar Dargah. His wife Zeenat Mahal died in 1886.

In a marble enclosure adjoining the dargah of Sufi saint, Qutbuddin Bakhtiar Kaki at Mehrauli, an empty grave or Sardgah marks the site where he had willed to be buried along with some of his Mughal predecessors, Akbar Shah II, Bahadur Shah I (also known as Shah Alam I) and Shah Alam II.

In

1959, the All India Bahadur Shah Zafar Academy was founded expressly to

spread awareness of his contribution to the first major anti - British

movement in India. Several movies in Hindi or Urdu have depicted his role during the rebellion of 1857. Roads bearing his name are found in New Delhi, Lahore, Varanasi, and other cities. A statue of Bahadur Shah Zafar has been erected at the Vijayanagaram palace in Varanasi. In Bangladesh, the Victoria Park in old Dhaka has been renamed "Bahadur Shah Zafar Park". And in several Pakistani cities, avenues, roads, shopping centers, and other landmarks carry the name of the last Mughal emperor.

Zafar was an accomplished Urdu poet and calligrapher. While

he was denied paper and pen in captivity, he was known to have written

on the walls of his room with a burnt stick. He wrote the following Ghazal as his own epitaph.

| Original Urdu | Devanagari transliteration | Roman transliteration | English Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

لگتا نہیں ہے جی مِرا اُجڑے دیار میں

|

|

|

|

In his book, The Last Mughal, William Dalrymple states that, according to Lahore scholar Imran Khan, the verse beginning umr-e-darāz māńg ke ("I asked for a long life") is probably not by Zafar, and does not appear

in any of the works published during Zafar's lifetime. The verse appears

to be by Simab Akbarabadi.

Fazl-e-Haq Khairabadi (1797–1861) was one of the main figures of the Indian Rebellion of 1857. He was a philosopher, a poet, a religious scholar, but is most remembered for his role as a freedom fighter. It was he who issued the fatwa in favor of Jihad against the English in 1857.

Khairabadi had been a chief judge in Lucknow. After the First War of Independence failed, he was arrested on 30 January 1859 at Khairabad, was found guilty of "revolt" against the Government and sentenced for life to the prison at Kalapani (Cellular Jail) with confiscation of his property by the Judicial Commissioner, Awadh Court. He reached Andaman on 8 October 1859 aboard the Steam Frigate “Fire Queen”.

His son, Abdul-ul-Haq, somehow managed to obtain the release order of his father. He reached Port Blair on 13 February 1861, but was too late — Khairabadi had been hanged on February 12.

Besides

being a scholar of Islamic studies and theology, he was also a literary

personage, especially Arabic and Persian literature. He edited the

first diwan of Mirza Ghalib on his request. On account of his deep knowledge and erudition he was called Allamah and later was venerated as a great Sufi.

Khairabadi writes:

| “ | The English prepared a scheme to Christianize all the Indian inhabitants. It was their belief that the Indians would not be able to find any helper and cooperator, and therefore save submit and obey, they would not have the nerve to defy them. The English had thoroughly realized that the ruler’s variance from the ruled on the basis of religion would be a great stumbling block in the way of domination and possession. Hence they began to indulge in all sorts of wiles and chicanery with complete diligence and assiduity, in their willful attempt to obliterate religion and the sense of nationhood. To teach small children and the ignorant and to inculcate their language and religion, they established schools in towns and villages and made an all out effort to wipe out the old sciences and academic attainments. | ” |

His grandson is Muztar Khairabadi, Jan Nisar Akhtar is his great - grandson, and Javed Akhtar and Salman Akhtar are his great - great - grandsons.

Aga Khan I (Persian: آغا خان اوّل; Āghā Khān-i Awwal or, less commonly but more correctly (Persian: آقا خان اوّل; Āqā Khān-i Awwal), was the title accorded to Hasan Ali Shah (Persian:حسن علی شاه; Ḥasan ‘Alī Shāh; 1804 in Kahak, Iran – 1881 in Bombay, India), the governor of Kirman, 46th Imam of the Nizari Ismaili Muslims, and prominent Muslim leader in Iran and later in the Indian Subcontinent.

The Imam Hasan Ali Shah was born in 1804 in Kahak, Iran, to Shah Khalil Allah, the 45th Ismaili Imam, and Bibi Sarkara, the daughter of Muhammad Sadiq Mahallati (d. 1815), a poet and a Ni‘mat Allahi Sufi. Shah Khalil Allah moved to Yazd in 1815, probably out of concern for his Indian followers, who used to travel to Persia to see their Imam and for whom Yazd was a much closer and safer destination than Kahak. Meanwhile, his wife and children continued to live in Kahak off the revenues obtained from the family holdings in the Mahallat (Maḥallāt) region. Two years later, in 1817, Shah Khalil Allah was killed during a conflict between some of his followers and local shopkeepers. He was succeeded by his eldest son Hasan Ali Shah, also known as Muhammad Hasan, who became the 46th Imam.

Unfortunately,

the family was left unprovided for after a conflict between the local

Nizaris and Imani Khan Farahani, who had been married to one of the late

Imam's daughters Shah Bibi and who had been in charge of the Imam's land holdings. The

young Imam and his mother moved to Qumm, but their financial situation

worsened. The Imam Hasan Ali Shah's mother decided to go to the Qajar

court in Tehran to obtain justice for her husband's death and was

eventually successful. Those who had been involved in the Shah Khalil

Allah's murder were punished and the Persian king Fath Ali Shah increased

Hasan Ali Shah's land holdings in the Mahallat region and gave him one

of his daughters, Sarv-i Jahan Khanum, in marriage. Fath Ali Shah also

appointed Hasan Ali Shah as governor of Qumm and

bestowed upon him the honorific of Aga Khan. Hasan Ali Shah thus become

known as Aga Khan Mahallati, and the title of Aga Khan was inherited by

his successors. Aga Khan I's mother later moved to India where she died

in 1851. Until Fath Ali Shah's death in 1834, the Imam Hasan Ali Shah

enjoyed a quiet life and was held in high esteem at the Qajar court.

Soon after the accession of Muhammad Shah Qajar to the throne of his grandfather, Fath Ali Shah, the Imam Hasan Ali Shah was appointed governor of Kerman in 1835. At the time, Kerman was held by the rebellious sons of Shuja al-Saltana, a pretender to the Qajar throne. The area was also frequently raided by the Afghans. Hasan Ali Shah managed to restore order in Kerman, as well as in Bam and Narmishair, which were also held by rebellious groups. Hasan Ali Shah sent a report of his success to Tehran, but did not receive any compensation for his achievements. Despite the service he rendered to the Qajar government, Hasan Ali Shah was dismissed from the governorship of Kerman in 1837, less than two years after his arrival there, and was replaced by Firuz Mirza Nusrat al-Dawla, a younger brother of Muhammad Shah Qajar. Refusing to accept his dismissal, Hasan Ali Shah withdrew with his forces to the citadel at Bam. Along with his two brothers, he made preparations to resist the government forces that were sent against him. He was besieged at Bam for some fourteen months. When it was clear that continuing the resistance was of little use, Hasan Ali Shah sent one of his brothers to Shiraz in order to speak to the governor of Fars to intervene on his behalf and arrange for safe passage out of Kerman. With the governor having interceded, Hasan Ali Shah surrendered and emerged from the citadel of Bam only to be double - crossed. He was seized and his possessions were plundered by the government troops. Hasan Ali Shah and his dependents were sent to Kerman and remained as prisoners there for eight months. He was eventually allowed to go to Tehran near the end of 1838 - 39 where he was able to present his case before the Shah. The Shah pardoned him on the condition that he return peacefully to Mahallat. Hasan Ali Shah remained in Mahallat for about two years. He managed to gather an army in Mahallat which alarmed Muhammad Shah, who travelled to Delijan near Mahallat to determine the truth of the reports about Hasan Ali Shah. Hasan Ali Shah was on a hunting trip at the time, but he sent a messenger to request permission of the monarch to go to Mecca for the hajj pilgrimage. Permission was given, and Hasan Ali Shah's mother and a few relatives were sent to Najaf and other holy cities in Iraq in which the shrines of his ancestors, the Shiite Imams are found.

Prior to leaving Mahallat, Hasan Ali Shah equipped himself with letters appointing him to the governorship of Kerman. Accompanied by his brothers, nephews and other relatives, as well as many followers, he left for Yazd, where he intended to meet some of his local followers. Hasan Ali Shah sent the documents reinstating him to the position of governor of Kerman to Bahman Mirza Baha al-Dawla, the governor of Yazd. Bahman Mirza offered Hasan Ali Shah lodging in the city, but Hasan Ali Shah declined, indicating that he wished to visit his followers living around Yazd. Hajji Mirza Aqasi sent a messenger to Bahman Mirza to inform him of the spuriousness of Hasan Ali Shah's documents and a battle between Bahman Mīrzā and Hasan Ali Shah broke out in which Bahman Mirza was defeated. Other minor battles were won by Hasan Ali Shah before he arrived in Shahr-i Babak, which he intended to use as his base for capturing Kerman. At the time of his arrival in Shahr-i Babak, a formal local governor was engaged in a campaign to drive out the Afghans from the city's citadel, and Hasan Ali Shah joined him in forcing the Afghans to surrender.

Soon after March 1841, Hasan Ali Shah set out for Kerman. He managed to defeat a government force consisting of 4,000 men near Dashtab, and continued to win a number of victories before stopping at Bam for a time. Soon, a government force of 24,000 men forced Hasan Ali Shah to flee from Bam to Rigan on the border of Baluchistan, where he suffered a decisive defeat. Hasan Ali Shah decided to escape to Afghanistan, accompanied by his brothers and many soldiers and servants.

After

arriving in Afghanistan in 1841, Hasan Ali Shah proceeded to Kandahar

which had been occupied by an Anglo - Indian army in 1839. A close

relationship developed between Hasan Ali Shah and the British, which

coincided with the final years of the First Anglo - Afghan War

(1838 – 1842). After his arrival, Hasan Ali Shah wrote to Sir William

Macnaghten, discussing his plans to seize and govern Harat on behalf of

the British. Although the proposal seemed to have been approved, the

plans of the British were thwarted by the uprising of Dost Muhammad's

son Muhammad Akbar Khan, who defeated the British - Indian garrison on its

retreat from Kabul in January 1842. The uprising spread to Kandahar

where the Afghans were in active hunt of the "infidel" Hasan Ali Shah.

Hasan Ali Shah managed to escape and helped to evacuate the British

forces from Kandahar in July 1842. The Afghans in Kandahar claimed that

they would not rest until they had captured the "traitor of the Ahl ul

Beit."

Hasan Ali Shah soon proceeded to Sind, where he rendered further services to the British. The British were able to annex Sind and for his services, Hasan Ali Shah received an annual pension of £2,000 from General Charles Napier, the British conqueror of Sind with whom he had a good relationship.

Hasan Ali Shah also aided the British militarily and diplomatically in their attempts to subjugate Baluchistan. He became the target of a Baluchi raid, likely in retaliation for his helping the British and to whom they considered a traitor and a "kufar" or infidel; however, Hasan Ali Shah continued to aid the British, hoping that they would arrange for his safe return to his ancestral lands in Persia, where many members of his family remained.

In October 1844, Hasan Ali Shah left Sind for Bombay, passing through Cutch (modern day Kutch) and Kathiawar where

he spent some time visiting the communities of his followers in the

area. After arriving in Bombay in February 1846, the Persian government

demanded his extradition from India. The British refused and only agreed

to transfer Hasan Ali Shah’s residence to Calcutta, where it would be

more difficult for him to launch new attacks against the Persian

government. The British also negotiated the safe return of Hasan Ali

Shah to Persia, which was in accordance with his own wish. The

government agreed to Hasan Ali Shah's return provided that he would

avoid passing through Baluchistan and Kirman and that he was to settle

peacefully in Mahallat. Hasan Ali Shah was eventually forced to leave

for Calcutta in April 1847, where he remained until he received news of

the death of Muhammad Shah Qajar. Hasan Ali Shah left for Bombay and the

British attempted to obtain permission for his return to Persia.

Although some of his lands were restored to the control of his

relatives, his safe return could not be arranged, and Hasan Ali Shah was

forced to remain a permanent resident of India. While in India, Hasan

Ali Shah continued his close relationship with the British, and was even

visited by the Prince of Wales when the future King Edward VII was on a

state visit to India. The British came to address Hasan Ali Shah as His

Highness. Hasan Ali Shah received protection from the British

government in British India as the spiritual head of an important Muslim

community.

The vast majority of his Khoja Ismaili followers in India welcomed him warmly, but some dissident members, sensing their loss of prestige with the arrival of the Imam, wished to maintain control over communal properties. Because of this, Hasan Ali Shah decided to secure a pledge of loyalty from the members of the community to himself and to the Ismaili form of Islam. Although most of the members of the community signed a document issued by Hasan Ali Shah summarizing the practices of the Ismailis, a group of dissenting Khojas surprisingly asserted that the community had always been Sunni. This group was outcast by the unanimous vote of all the Khojas assembled in Bombay. In 1866, these dissenters filed a suit in the Bombay High Court against Hasan Ali Shah, claiming that the Khojas had been Sunni Muslims from the very beginning. The case, commonly referred to as the Aga Khan Case, was heard by Sir Joseph Arnould. The hearing lasted several weeks, and included testimony from Hasan Ali Shah himself. After reviewing the history of the community, Justice Arnould gave a definitive and detailed judgement against the plaintiffs and in favour of Hasan Ali Shah and other defendants. The judgement was significant in that it legally established the status of the Khojas as a community referred to as Shia Imami Ismailis, and of Hasan Ali Shah as the spiritual head of that community. Hasan Ali Shah's authority thereafter was not seriously challenged again.

There is some evidence that the first Aga Khan was not initially well accepted by the Khoja community, a community that the British justice, Sir Joseph Arnould, gave him almost total control over. A. Meherally noted that that reports of the Aga Khan's drinking and womanizing may have contributed the Aga Khan's initial questionable acceptance:

| “ | Ismaili historians have recorded that until as late as 1874 (34 years after his arrival in India), the Aga Khan's authority as a religious leader was sharply opposed by some influential wealthy members of the community. His followers in Bombay objected to "his too great predilection for drinking and intriguing with females," according to Sir Richard Burton. | ” |