<Back to Index>

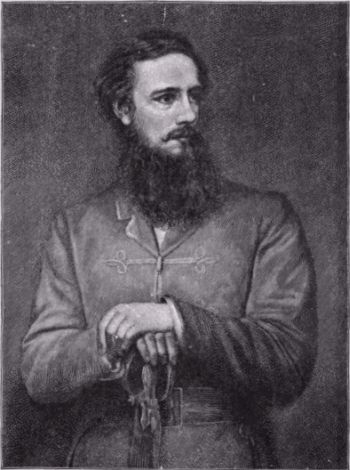

- Brigadier General of the British Army John Nicholson, 1822

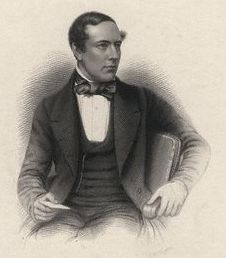

- Brevet Major of the British Army William Stephen Raikes Hodson, 1821

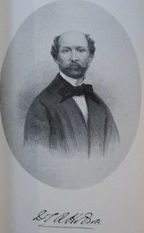

- Major General of the British Army Hugh Massy Wheeler, 1789

PAGE SPONSOR

Brigadier - General John Nicholson (11 December 1822 – 23 September 1857) was a Victorian era military officer known for his role in British India. A charismatic and authoritarian figure, Nicholson created a legend for himself as a political officer under Henry Lawrence in the frontier provinces of the British Empire in India. He was instrumental in the settlement of the North - West Frontier and played a legendary part in the Indian Mutiny.

Nicholson was born in Lisburn, Ireland, UK, the eldest son of Dr Alexander Jaffray Nicholson (who died when J.N. was eight) and Clara Hogg. He was privately educated in Delgany and later attended the Royal School Dungannon.

Nicholson's uncle obtained a cadetship for him in the Bengal Infantry of the British East India Company. He obtained his commission as Ensign on 24 February 1839 and landed at Calcutta in July the same year, from where he joined the 41st Native Infantry at Benares, being transferred 6 months later in December to the 27th Native Infantry at Ferozepore. He served in the First Anglo - Afghan War, during which he was taken prisoner by the Afghans and held for some time.

Involved in the First Anglo - Sikh War as a junior officer, he was taken under the wing of Henry Montgomery Lawrence along with several other similarly aged officers such as Herbert Edwardes, James Abbott, Neville Chamberlain, Frederick Mackeson, Patrick Alexander Vans Agnew, William Hodson, Reynell Taylor, Harry Burnett Lumsden, Henry Daly, John Coke, a group that was known as Henry Lawrence's young men, and was given much power as a political officer, and later a District Commissioner. He was feared for his foul temper and authoritarian manner, but also gained the respect of the Afghan tribes in the area for his fair - handedness and sense of honor. He inspired the short lived cult of Nikal Seyn.

Nicholson was best known for his role in the Indian Mutiny of 1857, planning and leading the Storming of Delhi. Famously dismissive of the incompetence of his superiors, he said, upon hearing of General Wilson's hesitancy, "Thank God I have yet the strength to shoot him, if necessary". One famous story recounted by Charles Allen in Soldier Sahibs is of a night during the Mutiny when Nicholson strode into the British mess tent at Jullunder, coughed to attract the attention of the officers, then said, "I am sorry, gentlemen, to have kept you waiting for your dinner, but I have been hanging your cooks." He had been told that the regimental chefs had poisoned the soup with aconite. When they refused to taste it for him, he force fed it to a monkey - and when it expired on the spot, he proceeded to hang the cooks from a nearby tree without a trial.

Nicholson never married, the most significant people in his life being his brother and Punjab administrators Sir Henry Lawrence and Herbert Edwardes. At Bannu, Nicholson used to ride one hundred and twenty miles every weekend to spend a few hours with Edwardes, and lived in his beloved friend's house for some time when Edwardes' wife Emma was in England. At his deathbed he dictated a message to Edwardes saying, "Tell him that, if at this moment a good fairy were to grant me a wish, my wish would be sleeping next to my Love, Edwardes." The love between him and Edwardes made them, as Edwardes' wife latter described it "more than brothers in the tenderness of their whole lives".

He

died on 23 September 1857, in a small bungalow in the cantonments of

Delhi, as a result of wounds received in the taking of the city nine

days previously. He was 34, not as the tombstone gives it, 35.

He became the Victorian "Hero of Delhi" inspiring books, ballads and generations of young boys to join the army. Nicholson is referenced in numerous literary works, including Rudyard Kipling's Kim, in which the protagonist, Kim, meets an aged Rissaldar - Major (a native NCO of Cavalry). The man turns out to be a veteran of the Great Uprising of 1857, and in his interaction with Kim, he is said to sing the old song of Nikal Seyn before Delhi.

Nicholson

features in a number of novels about this period in history. He is

mentioned by George MacDonald Frazier in his book Flashman and the Great

Game, in which Flashman meets Nicholson on the road between Bombay and

Jansi just before the mutiny, he describes Nicholson as "The downiest

bird in all India and could be trusted with anything, money even." This

from Flashman is a rare compliment. He also appears as one of the main

characters in James Leasor's novel about the Indian Mutiny, 'Follow the Drum', which describes his death in some detail.

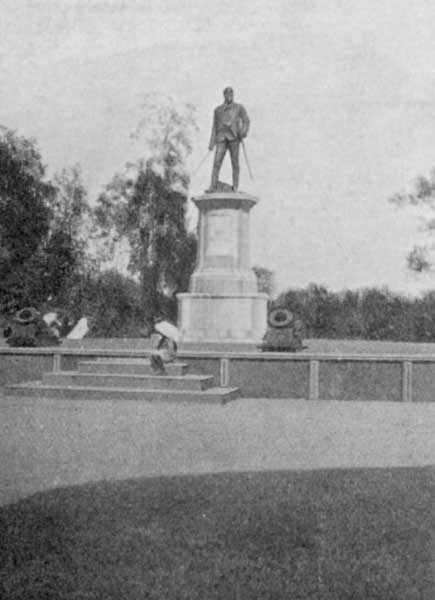

Brigadier - General John Nicholson's tombstone, made from a white marble slab near Delhi’s Kashmir gate, was a former garden seat of the Mughals. His gallant service and untimely death are commemorated on a white marble memorial plaque at the Mutiny Memorial, on the Ridge in New Delhi. A large statue of Nicholson showing him with a naked sword in hand and surrounded by mortars was erected in his honor in Delhi, but was taken down when India became independent and later removed to the Royal School Dungannon, his old school.

A granite obelisk (Nicholson's obelisk) was erected in 1868 at Margalla hills near Rawalpindi as a monument to pay tribute to his valor.

A tablet in the church at Bannu where Nicholson served as Deputy Commissioner from 1852 - 1854 carries the following inscription: “Gifted in mind and body, he was as brilliant in government as in arms. The snows of Ghazni attest his youthful fortitude; the songs of the Punjab his manly deeds; the peace of this frontier his strong rule. The enemies of his country know how terrible he was in battle, and we his friends have to recall how gentle, generous, and true he was.”

One

of the four Houses of the Royal School Dungannon is named after him,

having yellow as its colors. It is the youngest House at the school.

Brevet Major William Stephen Raikes Hodson (10 March 1821 – 11 March 1858) was a British leader of irregular light cavalry during the Indian Rebellion of 1857(also known as India's First War of Independence or the Indian Mutiny). He was known as "Hodson of Hodson's Horse."

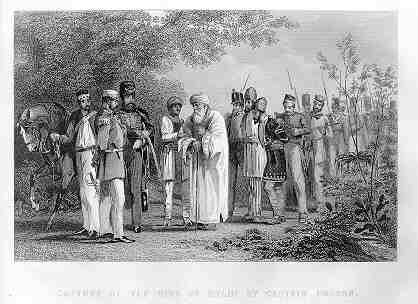

His most notable action was to apprehend the Emperor of India. The following day he rode to the enemy camp, heavily outnumbered by the rebels and demanded the surrender of the Mughal princes who were leading the rebellion around Delhi and killed them.

Hodson is credited with being jointly responsible for the introduction of the khaki uniform.

William Hodson was born on 9 March 1821 at Maisemore Court, near Gloucester, third son of the Rev. George Hodson. He was educated at Rugby School under Dr Arnold and at Trinity College, Cambridge. He accepted a cadetship in the Indian Army at the age of twenty - three; joining the 2nd Bengal Grenadiers, he went through the First Anglo - Sikh War.

Unusually among officers of the time, William Hodson was a Cambridge graduate and keen linguist. A contemporary described him as tall man with yellow hair, a pale, smooth face, heavy moustache, and large, restless, rather unforgiving eyes… a perfect swordsman, nerves like iron, and a quick, intelligent eye. Hodson delighted in fighting and his favorite weapon was the hog spear. He was a brilliant horseman with the capacity to sleep in the saddle. He was described as 'the finest swordsman in the army'.

The initial assistance he gave in organizing the newly formed Corps of Guides in December 1846 had been one of Sir Henry Lawrence's projects in which Hodson excelled. The Guides Corps had Lt Harry Burnett Lumsden as its commandant and Lt Hodson as adjutant. Significantly, among the duties assigned to Hodson was responsibility for equipping the new regiment which necessitated his choosing the regiment's uniform. Accordingly in May 1848 he liaised with his brother Rev. George Hodson, in England, to send all the cloth, rifles and Prussian style helmets required. With Lumsden's approval, Hodson decided upon a lightweight uniform of Khaki color - or 'drab' as it was then referred to. This would be comfortable to wear and 'make them invisible in a land of dust'. As a result Hodson and Lumsden had the joint distinction of being the first officers to equip a regiment dressed in Khaki which many view it as the precursor of modern camouflage uniform. Within a short time he was not only commanding the regiment but had established himself as one of the foremost intelligence authority in India.

He was transferred to the Civil Department as Assistant Commissioner in 1849 and stationed at Amritsar; from there he traveled in Kashmir and Tibet. In 1852 he was appointed Commandant of the Guide Corps.

At the outset of the Indian Mutiny he made his name by riding with dispatches from General Anson from Karnal to Meerut and back again, a distance of 152 miles in seventy - two hours, through country full of hostile cavalry. Following this feat, the commander - in - chief empowered him to raise and command a new regiment of 2000 irregular horse, which became famed as "Hodson's Horse", and placed him at the head of the Intelligence Department.

In his double role of cavalry leader and intelligence officer, Hodson played a large part in the reduction of Delhi.

His major achievement was the capture of the Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Shah II and the execution of the three Mughal princes: Bahadur's sons Mirza Mughal and Mirza Khizr Sultan and his grandson Mirza Abu Bakr.

The

British knew that the old Emperor (or "King of Delhi") was proving to

be a focus for the uprising and the mutineers, and that he, his sons and

their army were camped just outside Delhi at Humayun's Tomb.

The General in command said he could not spare a single European.

Hodson volunteered to go with 50 of his irregular horsemen, this request

was turned down but after some persuasion Hodson obtained from General Wilson permission

to ride out to where the enemy were encamped. Hodson rode 6 miles

through enemy territory into their camp, containing some 6000+ armed

mutineers, who are said to have laid their arms to grounds when he

ordered them to. This was highly symbolic of the decline of the Turks

and Mughals which started after Aurangzeb.

Here he accepted the surrender of Bahadur Shah II, the last of the Moghul Emperors of India, promising him that his life would be spared. The capture of the Emperor in the face of a threatening crowd dealt the mutineers a heavy blow. As a sign of surrender the Emperor handed over his arms, which included two magnificent swords, one with the name ‘Nadir Shah’ and the other with the seal of Jahangir engraved upon it, which Hodson intended to present to Queen Victoria. The swords he took from the Emperor were given to the Queen as a symbol of the Emperor's surrender and are still held in the Queen's Collection.

The sons of the king, the princes had refused to surrender and on the following day with few horsemen Hodson went back and demanded the princes' unconditional surrender. Again a crowd of thousands of mutineers gathered, and Hodson ordered them to disarm, which they did. He sent the princes on with an escort of ten men, while with the remaining ninety he collected the arms of the crowd. On going after the princes, Hodson found the crowd was again pressing towards the escort. The princes were mounted on a bullock - cart and driven towards the city of Delhi. As they approached the city gate, Hodson ordered the three princes to get off the cart and to strip naked. He then shot them dead before stripping the princes of their signet rings, turquoise arm bands and bejeweled swords. Their bodies were thrown in front of a kotwali, or police station, and left there to be seen by all. The gate near where they were killed is called the Khooni Darwaza, or Bloody Gate.

This action was controversial at the time, the future Frederick Roberts, 1st Earl Roberts,

then a junior officer serving in the Delhi campaign would later call it

a "blot" and criticized "an otherwise brilliant officer" for exposing

himself to criticism. Other first hand accounts, such as William Ireland also

called into question the exigency of the execution. His service record

showed that he had often behaved in arbitrary fashion before, and he had

previously been removed from civil duties by the then Governor General

of India, Lord Dalhousie, a man not himself noted for restraint or strict adherence to legal nuance.

In 1855, two separate charges were brought against Hodson. The first was that he had arbitrarily imprisoned a Pathan chief named Khadar Khan, on suspicion of being concerned in the murder of Colonel Mackeson. The man was acquitted, and Lord Dalhousie removed Hodson from his civil functions and remanded him to his regiment on account of his lack of judgment.

The second charge was more serious, amounting to an accusation of misappropriation of the funds of his regiment. He was tried by a court of inquiry, who found that his conduct to natives had been unjustifiable and oppressive, that he had used abusive language to his native officers and personal violence to his men, and that his system of accounts was calculated to screen peculation and fraud. However, a subsequent inquiry was carried out by Major Reynell Taylor, which dealt simply with Hodson's accounts and found them to be an honest and correct record irregularly kept.

During a tour through Kashmir with

Sir Henry Lawrence he kept the purse and Sir Henry could never obtain

an account from him; subsequently, Sir Henry's younger brother Sir George Lawrence accused him of embezzling the funds of the Lawrence Asylum at Kasauli; while Sir Neville Chamberlain in

a published letter says of the third brother, Lord Lawrence, "I am

bound to say that Lord Lawrence had no opinion of Hodson's integrity in

money matters. He has often discussed Hodson's character in talking to

me, and it was to him a regret that a man possessing so many fine gifts

should have been wanting in a moral quality which made him

untrustworthy." Finally, on one occasion Hodson spent £500 of the

pay due to Lieutenant Godby, and under threat of exposure was obliged to

borrow the money from a local banker named Bisharat Ali through one of

his officers.

On 11 March 1858 Hodson's regiment was in Lucknow and while storming the Begam's palace (Begum Kothi) he was shot mistakenly. His last words were ‘I hope I have done my duty’.

On the evening of 12 March 1858, his body was buried in the garden of La Martiniere Lucknow.

His grave and memorial is still located within the grounds of La

Martiniere College. His grave bears the inscription 'Here lies all that

could die of William Stephen Raikes Hodson'.

Though the British Empire looked upon Hodson as somewhat of a hero, he is remembered in India mostly for his excesses while trying to curb the 1857 Revolt. He is also remembered for a number of notable achievements in his lifetime. His military career won him respect and praise from many quarters; this included recognition from the Secretary of State for India, the Prime Minister and Queen Victoria.

In parliamentary speeches made on 14 April 1859 the Prime Minister Earl of Derby, and the Minister for India Lord Stanley, singled out Major Hodson for his unique services to the country. Lord Stanley is quoted as saying:

"Major Hodson, of the Guides, who, in his short but brilliant military career, displayed every quality which a cavalry officer should possess. Nothing is more remarkable in glancing over the biography of Major Hodson that has just appeared than the variety of services in which he was engaged, unless it be the energy and versatility with which he turned from one to the other. At one time displaying his personal courage and skill as a swordsman in conflict with the Sikh fanatics; then transferred to the Civil Service, the duties of which he performed as though he had passed his whole life at the desk; afterwards recruiting and commanding the corps of Guides, and, lastly, taking part in the operations before Delhi, volunteering for every enterprise in which life could be hazarded or glory could be won; he crowded into the brief space of twelve eventful years the services and adventures of a long life. He died before the reward which he had earned could be received, but he attained that reward which doubtless he most coveted — the consciousness of duty nobly done, and the assurance of enduring military renown."

The Prime Minister said of him

"Doubtless many have fallen who, if they had been spared, might have risen to greatest eminence and have held the highest stations in public service. I allude to Hodson a model of chiefs of irregular forces. By his valour, his rigid discipline, and careful attention to his men's real wants, comforts, desires, and even prejudices, he had obtained an influence which was all but marvellous. This enabled him to lead his troops so formed and disciplined into any danger and into any conflict as if they had been British soldiers. He has met a soldier's death. It will be long before the people lose the memory of Hodson".

General Hugh Gough said of him,

"A finer or more gallant soldier never breathed. He had the true instincts of a leader of men; as a cavalry soldier he was perfection; a strong seat, a perfect swordsman, quick and intelligent"

This recognition of Hodson by the Prime Minister was reflected in the special pension granted his widow by the Secretary of State for India in Council, who declared it was 'testimony of the high sense entertained of the gallant and distinguished services of the late Brevet - Major W.S.R. Hodson' and Her Majesty Queen Victoria honored Major Hodson posthumously by granting his widow private apartments at Hampton Court Palace "in consideration of the distinguished service of your late husband in India".

He features as one of the main characters in James Leasor's novel about the Indian Mutiny, 'Follow the Drum', which describes his part in these events and his death in some detail.

The following verses by Sir Mortimer Durand appeared in India shortly after Hodson's death:

I rode to Delhi with Hodson: there were three of my Father's sons;

Two of them died at the foot of the ridge, in the line of the Mori's guns.

I followed him on when the great town fell; he was cruel and cold they said:

The men were sobbing around the day that I saw him dead.

It is not soft words that a soldier wants; we know what he was in fight;

And we love the man that can lead us, ay, though his face be white.

And when the time shall come, sahib, as come full well it may,

When all things are not fair and bright, as all things seem today,

When foes are rising round you fast, and friends are few and cold

And half a yard of trusty steel is worth a prince's gold

Remember Hodson trusted us, and trust the old blood too,

And as we followed him - to death - our sons will follow you.

Sir Hugh Massy Wheeler KCB (30 June 1789 – 1857) was a Major General in

the British Army stationed in India, who successfully commanded a

military force of 4,500 British and Indian soldiers (known as Sepoys), in the First Anglo - Sikh War, as well as the battles of Mudki (Moodkee), Ferozeshah, and Aliwal.

In 1850, Wheeler took command of Cawnpore (now Kanpur) in India. While the command of the government and military forces fell under the rule of the British, 96 percent of Wheeler's army of 300,000 soldiers consisted of men that were native to India. In 1857, India asserted their First War of Independence, during which Wheeler, as Major General, notably led British forces at the Siege of Cawnpore.

Hugh Wheeler was born 30 June 1789 at Ballywire, County Limerick, Ireland. He was the son of Captain Hugh Wheeler of the Indian army and Hon Margaret Massy. He was schooled at Richmond, Surrey and at Bath Grammar. He married Francis Oliver née Marsden 1842. Together, they had nine children.

In 1803, Wheeler joined the military branch of the East India Company and received his first commission in the Bengal Infantry. The following year, he marched under the leadership of Lord Gerard Lake, 1st Viscount Lake, against Delhi. Having risen steadily through the ranks, he became colonel of the 48th Bengal Native Infantry,

which was part of the organization of the British Colonial Army. He was

appointed first - class brigadier, in command of the field forces.

In early December 1845, previous to the hard fought Mudki (Moodkee) and the Battle of Ferozeshah, Wheeler commanded a military force of 4,500 men and 21 guns during the First Anglo - Sikh War. The majority of the men under his rule were Indian soldiers, or Sepoys. Wheeler commanded and protected the village of Bussean, where the military depot storehouse had been established for the armies under the command of Sir Henry Hardinge, 1st Viscount Hardinge; Sir Hugh Gough, 1st Viscount Gough; and Sir Harry Smith, 1st Baronet of Aliwal. The successful containment at Bussean contributed to the victory overall, resulting in temporarily driving the Sikhs from the rest of their fortifications.

Over the months of December 1845 and January 1846, the Sikh and British Armies rallied and retreated numerous times, culminating in the Battle of Aliwal on 28 January 1846, during which, Brigadier - General Wheeler commanded a distinguished part in the battle. This victory effectively broke the Sikh army.

In October 1848, Wheeler successfully conquered the Sikh armies at the fortress of Rungur Nuggul (modern name: Rangar Nangal),

which was a small village of Punjab, India. The defeat of the Punjabi

resulted in the loss of one soldier under Wheeler's command. Wheeler's

military prowess and expertise as evidenced through this conquest earned

the respect and approval of Lord Gough, then Commander - in - Chief of the

British forces, who formally congratulated Wheeler. Gough's official

statement confirmed that, in his opinion, the military success of the

operations under the command of Wheeler was "entirely to be ascribed to

the soldier - like and judicious arrangements of that gallant officer."

For his service at Rungur Nuggul, Wheeler received the Order of the Dooranee Empire and was appointed one of the personal assistants to Her Majesty, Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. In November 1848, a military directive addressed to the Governor - General, Lord Gough stated that he "has directed the Adjutant - General to convey to Brigadier - General Wheeler his hearty thanks for the important services which he and the brave troops under his command have rendered in the reduction of the fortress of Kullalwalhah," again with the loss of only one man killed and five wounded.

On 30 January 1849, a dispatch was received from the Adjutant - General at the Camp before Chillianwallah, to the Governor - General stated that "Brigadier Wheeler, in command of the Punjab division and of the Jullundur field force, assaulted and captured the heights of Dulla in the course of his operations against the rebel Ram Singh, in spite of the utmost difficulties."

In the general military order issued by Sir Walter Gilbert, KCB, upon receiving the announcement of the end of hostilities in the Punjab, the Governor - General expressed high praise of Wheeler stating, "Brigadier - General Wheeler, C.B., has executed the several duties which have been committed to him with great skill and success, and the Governor - General has been happy in being able to convey to him his thanks thus publicly."

In

1850, after having received widespread recognition and appreciation by

the Governor - General and Commander - in - Chief for his valuable service in

the Sikh campaigns and in the conquest of the Punjab, he was made a Knight Commander in the Order of the Bath (KCB).

The Indian action seen during the war in the Punjab clearly confirm

that the honors conferred upon Wheeler were valiantly deserved. In

1854, he attained the rank of Major General. From that point forward, he

held command of the district of Cawnpore.

When Wheeler took command of Cawnpore (now Kanpur) in India, the country had been divided, consisted of hundreds of independent states, with the British ruling less than half of the country, leaving the British East India Company in charge. While the command of the government and military forces fell under the rule of the British, 96 percent of Wheeler's army of 300,000 soldiers (or Sepoys), consisted of men that were native to India. The Indian soldiers were crucial in securing the subcontinent for the British East India Company.

India's government and military rule was motivated by commerce. Great Britain's manufacturers were receiving raw cotton from India, while the British were exporting manufactured goods in return. One tenth of Britain's exported manufactured goods were being shipped to India. The British East India Company, acting as the government in India, was paying the expense of troops to defend their commercial interests, saving the budget conscious British government this expense.

The commercial monopoly and absolute rule of the British East India Company effectively rendered India's historical royal house and princely rulers to mere puppets of the East India Company. If an Indian prince or member of the royal house failed to cooperate with the company, the absolute rule could arbitrarily dispose of him and annex his territory, removing him from power using the Indian troops (Sepoys) employed by Major General Wheeler. For many years, bitterness and resentment of continued British encroachment festered among the native citizens of India.

On 10 May 1857, there was widespread mutiny among the Indian soldiers of the Bengal Army, resulting in the Indian Rebellion of 1857. The rebellion is known as India's First War of Independence.

When the mutiny of the Indian soldiers had spread over the country around the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, Major General Wheeler, with a small body of soldiers, some civilians, with their wives and children, fortified themselves against the ensuing Indian rebels. Wheeler tried to lessen the possibility of an Indian Rebellion at Cawnpore by sending his Sepoys away from his men "on missions" to the cantonment town of Fatehgarh in the state of Uttar Pradesh, India. This failed, and the rebellion started.

On 5 June 1857, Wheeler received a message from Nana Sahib,

who was the leader of the Rebels, that announced an anticipated attack

from Sahib's men the following day at 10:00 a.m. The message

received from Sahib came as a surprise. Wheeler was not expecting the

Sahib led rebels to attack him at Cawnpore. Wheeler rationalized that he

was not only a veteran and respected soldier, but also married to a

high caste Indian woman. He relied on his own prestige, and his friendly

relations with Sahib to

defer overt rebellion. Under these assumptions, Wheeler took

comparatively few measures to secure refuge for his family and the women

and children that relied on him for protection. Sahib's announcement

offered little time to prepare fortifications and gather sufficient

supplies and ammunition to survive the impending battle.

The Indians arrived at 10:30 a.m. on the expected day. Wheeler found himself under siege by 4,000 Rebels led by Sahib. The Indian soldiers that had previously been under the command of Major General Wheeler rebelled and overtook the European fort.

When the mutiny broke out, it was generally believed that, whoever else might fail, Wheeler would be equal to the occasion. Although he was considerably older than when he successfully commanded earlier military conquests, Wheeler maintained his physical strength and vigor, as well as his intellect and military instinct. He had proven himself on many hard fought fields to be a brave and determined soldier. He was known to be acquainted with the character and to possess the confidence of the Sepoys to a special degree. In one respect, he stood out from the crowd of British officers. He realized that while it would be desirous that his men remain faithful, in all likelihood, they would prove themselves as traitors.

Wheeler

led his men in a sharp defense for over three weeks. Even though

ill prepared, he managed to hold off several Indian assaults. They made a

valiant effort resisting the violent advances of their former comrades

turned traitors, who, under the command of Sahib, surrounded the town in

large numbers. By 21 June, the British lost one third of their army.

Wheeler kept in contact with Henry Lawrence in Lucknow, seeking military reinforcements. However, Lawrence was also under siege. Wheeler's men were demoralized.

Wheeler endured three weeks of the Siege of Cawnpore with little water or food, suffering continuous casualties to men, women, and children. On 25 June, Sahib made an offer of safe passage to Allahabad. With the provisions of the garrison exhausted, and no hope of relief or reinforcements, Sir Hugh Wheeler agreed to the proposal made by Sahib, by which the garrison and their helpless charges were to be permitted to leave in boats, and to pass down the Ganges to Benares.

Early in the morning of 27 June, with barely three days' food rations remaining, the European party left their fortress with their small arms and made their way to the Satichaura Ghat where boats provided by Sahib were waiting to take them to Allahabad. The actions of the mutineers during the attempt to leave, resulted in an all out bloody massacre. After hearing bugles from the banks, the Indians jumped off their boats into the river. As they jumped, gunfire opened up from concealed embankments, and flaming arrows were shot into the straw roof of the boats, setting some boats ablaze. The fugitives who survived death in the water were brought back on shore and summarily executed. Wheeler, along with all of his men, was killed on the river or re-captured and executed.

Several Indian soldiers who had remained loyal to Wheeler and the Company were removed by the mutineers and killed, for either their loyalty or their conversion to the Christian faith. A few injured British officers trailing the group of Europeans attempting to escape were apparently hacked to death by angry Sepoys.