<Back to Index>

- Architect Henry Hobson Richardson, 1838

- Architect Louis Henri Sullivan, 1856

PAGE SPONSOR

Henry Hobson Richardson (September 29, 1838 – April 27, 1886) was a prominent American architect who designed buildings in Albany, Boston, Buffalo, Chicago, Pittsburgh, and other cities. The style he popularized is named for him: Richardsonian Romanesque. Along with Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, Richardson is one of "the recognized trinity of American architecture".

Richardson was born at Priestly Plantation in St. James Parish, Louisiana, and spent part of his childhood in New Orleans, where his family lived on Julia Row in a red brick house designed by the architect Alexander T. Wood. He was the great - grandson of inventor and philosopher Joseph Priestley, who is usually credited with the discovery of oxygen.

Richardson went on to study at Harvard College and Tulane University. Initially, he was interested in civil engineering, but shifted to architecture, which led him to go to Paris in 1860 to attend the famed École des Beaux Arts in the atelier of Louis - Jules André. He was only the second U.S. citizen to attend the École's architectural division, — Richard Morris Hunt was the first — and the school was to play an increasingly important role in training Americans in the following decades.

He didn't finish his training there, as family backing failed due to the U.S. Civil War.

Richardson returned to the U.S. in 1865. The style that Richardson developed over time, however, was not the more classical style of the École, but a more medieval - inspired style, influenced by William Morris, John Ruskin and others. Richardson developed a unique and highly personal idiom, adapting in particular the Romanesque of southern France. His early works, however, were not very remarkable. "There are few hints in the mediocre work of Richardson's early years of what was to come in his maturity, when, beginning with his competition - winning design... for the Brattle Square Church in Boston, he adopted the Romanesque."

In 1869, he designed the Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane (now known as the H.H. Richardson Complex) in Buffalo, the largest commission of his career and the first appearance of his eponymous Richardsonian Romanesque style. A massive Medina sandstone complex, it is a National Historic Landmark and, as of 2009, was being restored.

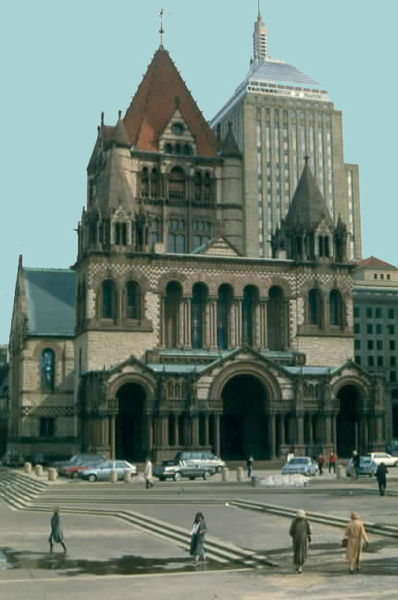

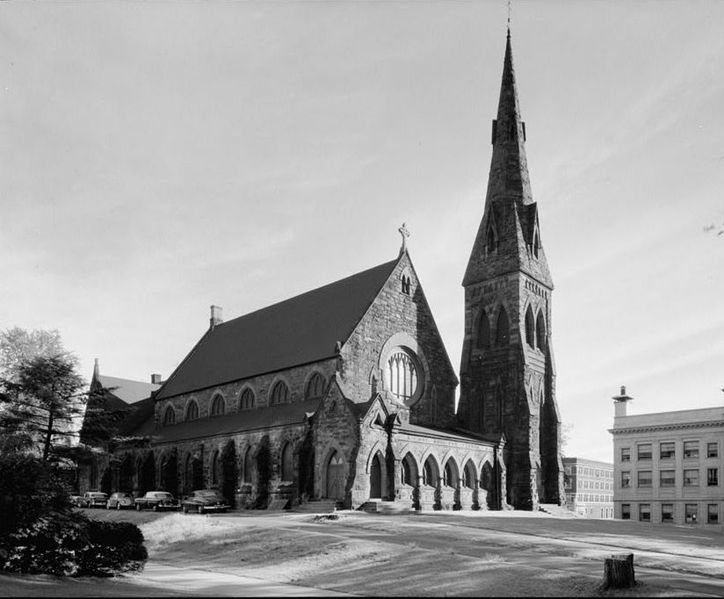

The 1872 Trinity Church in Boston solidified Richardson's national reputation and led to major commissions for the rest of his life. Although incorporating historical elements from a variety of sources, including early Syrian Christian, Byzantine, and both French and Spanish Romanesque, it was more "Richardsonian" than Romanesque. Trinity was also a collaboration with the construction and engineering firm of the Norcross Brothers, with whom the architect would work on some 30 projects.

He was well - recognized by his peers; of ten buildings named by American architects as the best in 1885, fully half were his: besides Trinity Church, there were Albany City Hall, Sever Hall at Harvard University, the New York State Capitol in Albany (as a collaboration), and Town Hall in North Easton, Massachusetts.

Despite the success of Trinity, Richardson built only two more churches, focusing instead on the monumental buildings he preferred, plus libraries, railroad stations, commercial buildings, and houses. Of his buildings, the two he liked best, the Allegheny County Courthouse (Pittsburgh, 1884 - 1888) and the Marshall Field Wholesale Store (Chicago, 1885 - 1887, demolished 1930), were completed posthumously by his assistants.

Richardson died in 1886 at age 47 of Bright's disease, a historical term for the kidney disorder chronic nephritis. On his last day, he signed an informal will directing the three assistants still remaining to carry on the business, which was soon formalized as Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge.

Despite an enormous income for an architect of his day, his "reckless disregard for financial order" meant that he died deeply in debt, leaving little to his widow and six children. He was buried in Walnut Hills Cemetery, Brookline, Massachusetts.

Richardson spent much of his later years in his house in Brookline, Massachusetts, which had a studio attached to ease the strain on his health. The house fell into disrepair and was listed in 2007 as an endangered historic site. However, the house was purchased in January 2008 for roughly $2 million with an amended deed requiring that the building be historically restored. The house is on a hill, where Richardson could supposedly watch construction of the Trinity Church in Copley Square, from his second story window.

Richardson's most acclaimed early work is Trinity Church. The interior of the church is one of the leading examples of the arts and crafts aesthetic in the United States. It was at Trinity that Richardson first worked with Augustus Saint Gaudens, with whom he would work many times in the ensuing years. Across the square is the Boston Public Library, built later (1895) by Richardson's former draftsman, Charles Follen McKim.

Together these and the surrounding buildings comprise one of the

outstanding American urban complexes, built as the centerpiece of the

newly developed Back Bay.

Richardson pointedly claimed ability to create any type of structure a client

wanted, insisting he could design anything "from a cathedral to a

chicken coop." "The things I

want most to design are a grain elevator and the interior of a great

river - steamboat." However, architectural historian James F. O'Gorman sees

Richardson's achievement particularly in four building types: public

libraries, commuter train station buildings, commercial buildings, and single - family houses.

A series of small public libraries donated by patrons for the improvement of New England towns makes a small coherent corpus that defines Richardson's style: libraries in Woburn, North Easton, Malden, Massachusetts, the Thomas Crane Public Library (Quincy, Massachusetts), and Billings Memorial Library on the campus of the University of Vermont. These buildings seem resolutely anti - modern, with the atmosphere of an Episcopalian vicarage, dimly lit for solemnity rather than reading on site. They are preserves of culture that did not especially embrace the contemporary flood of newcomers to New England. Yet they offer clearly defined spaces, easy and natural circulation, and they are visually memorable. Richardson's libraries found many imitators in the "Richardsonian Romanesque" movement.

The Thomas Crane Public Library is regarded as the best of Richardson's libraries. In his earlier libraries, Richardson's approach was to conceive the parts and then assemble them, while in the later ones such as Crane he thought in terms of the whole. Richardson also engaged in a process of simplification and elimination with each successive library, until in Crane "Richardson's concentration on the relation of solid to void, of wall to window, becomes the basis for a harmonious abstraction with scarcely a reference to any past style."

Richardson also designed nine railroad station buildings for the Boston & Albany Railroad as

well as three stations for other lines. More subtle than his churches,

municipal buildings and libraries, they were an original response to

this relatively new building type. Beginning with his first at

Auburndale (1881, demolished 1960s), Richardson drew inspiration for

these station buildings from Japanese architecture that he learned about from Edward S. Morse, a Harvard zoologist who

began traveling to Japan in 1877, originally for biological specimens.

Falling in love with Japan, upon his return that same year Morse began

giving illustrated "magic lantern" public lectures on Japanese ceramics, temples, vernacular architecture, and culture. Richardson incorporated Japanese concepts "in both silhouette and spatial concept", including the karahafu ("excellent

gable", but generally poorly translated as "Chinese gable" despite its

Japanese origin), the eyelid dormer, and the wide hip roof with extended

eaves, all shown by Morse.

Among the few stations still extant, these influences are perhaps best illustrated in his Old Colony station (Easton, Massachusetts, 1881 - 1884). Here he uses the Syrian arch that became a hallmark of Richardson designs for both the porte - cochère and the windows of the main structure. Reminiscent of a courtyard and temple that Morse illustrated from Nikkō in Tochigi prefecture, Japan, the hip roof on wide, bracketed eaves nearly hides the rough stonework below in shadow. Richardson even included a carved dragon at each end of the beam spanning the arches of windows. The walls "become horizontal planes hovering above one another with bands of windows in between."

Richardson was early although not the first U.S. architect to look to Japan, but his train stations "form the earliest sustained application of Japanese inspiration in American architecture, an undeniable precursor to Frank Lloyd Wright's Prairie house designs". As with his libraries, Richardson evolved and simplified as the series continued, and his famous Chestnut Hill station (Newton, Massachusetts, 1883 - 1884, demolished circa 1960) featured clean lines with less Japanese influence.

After his death, more than 20 other stations were designed in Richardson's style for the Boston and Albany line by the firm of Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge, all draftsmen of Richardson at the time of his death. Many Boston and Albany stations were landscaped by Richardson's frequent collaborator, Frederick Law Olmsted. Additionally, a railroad station in Orchard Park, New York (near Buffalo) was built in 1911 as a replica of Richardson's Auburndale station in Auburndale, Massachusetts. The original Auburndale station was torn down in the 1960s during construction of the Massachusetts Turnpike. The original Richardson stations on the Boston and Albany line have either been demolished or converted to new uses (such as restaurants). Two of the stations designed by Shepley, Rutan, and Coolidge (both in Newton, Massachusetts) are still used by Boston's MBTA (green line) public transit service.

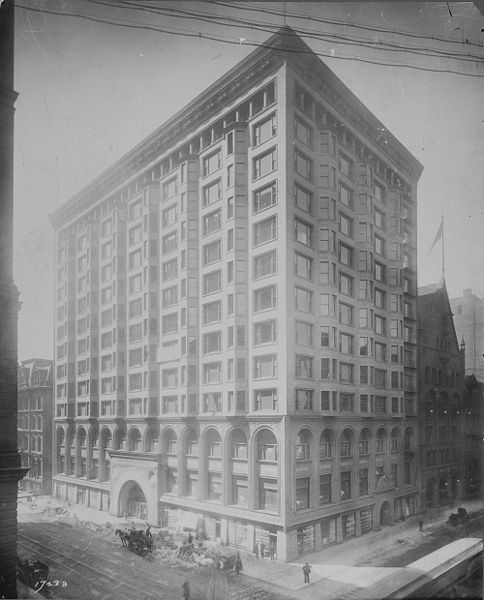

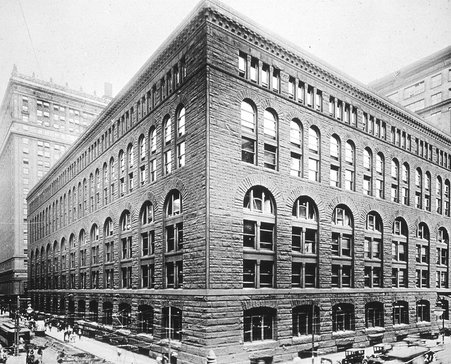

The noted Marshall Field Wholesale Store (Chicago, 1885 - 1887, demolished 1930) is Richardson's "culminating statement of urban commercial form", and its remarkable design influenced Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, and many other architects. According to Jeffrey Karl Ochsner, who has compiled all of Richardson's architectural works, despite its demolition in 1930, the Marshall Field Wholesale Store "is probably the most famous of Richardson's buildings, one that Richardson himself saw as among his most significant." Architectural critic Henry - Russell Hitchcock states that in the Field Store, Richardson "was, perhaps, never more creative architecturally." Drawing from his own earlier work and both Romanesque and Renaissance precedents, Richardson designed this "massive but integrated" seven - story stone warehouse. Minimizing ornamentation in an era that employed lots of it, he stressed what he termed "the beauty of material and symmetry rather than mere superficial ornamentation" with "the effects depending on the relations of 'voids and solids'... on the proportion of the parts." Not requiring the new steel frame technology because of its comparatively low height, Richardson used multi - storied windows topped by arches to tie the stories together, and the regular patterns of the windows to tie the entire building into "a simple and unified solid occupying an entire block."

Richardson designed many important single - family residences, but his famous John J. Glessner House (Chicago, 1885 - 1887) is his best and most influential urban house, and the Mary Fisk Stoughton House (Cambridge,

Massachusetts, 1882 - 1883) and Henry Potter House (St. Louis, 1886 -

1887, demolished 1958) play that role for suburban and country settings. The Glessner House in particular influenced Frank Lloyd Wright as he began developing what would become his Prairie School houses.

- Buffalo's New York State Asylum (1870) was the largest building of the master's career and the first to display his characteristic style. The complex was also the first of many projects on which he worked with Frederick Law Olmsted.

- Sever Hall, Harvard University (1880), brickwork, with molded brick string courses with turrets embedded in the walls, strips of windows, under a huge hipped roof as well as Austin Hall (Harvard University) (1882 – 1884) which followed a more traditional Richardson motif.

- Emmanuel Episcopal Church (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), noted for its fine brickwork, nicknamed "the Bake Oven Church".

- New York State Capitol (oversight and partial contribution)

- Warder Mansion, Washington, DC

- The Allegheny County Courthouse, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, (1883 – 1888) connected by a "Bridge of Sighs" to its jail across a street: cyclopean masonry and a tall tower

Richardson is one of few architects to be immortalized by having a style named after him. "Richardsonian Romanesque", unlike Victorian revival styles like Neo - Gothic, was a highly personal synthesis of the Beaux - Arts predilection for clear and legible plans, with the heavy massing that was favored by the pro-medievalists.

Significant to Richardson's style was his picturesque massing and roofline profiles, along with his mastery of rustication and polychromy, semi - circular arches supported on clusters of squat columns, and round arches over clusters of windows on massive walls.

Following his death, the Richardsonian style was perpetuated by a variety of proteges and other architects, many for civic buildings like city halls, county buildings, court houses, train stations and libraries, as well as churches and residences. These include:

- the successor firm of Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge, who completed some two dozen unfinished projects and then continued to produce work in the same style, and continued to employ his collaborators the Norcross Brothers for construction and engineering expertise, Frederick Law Olmsted for landscape architecture, and the English sculptor John Evans for stone carving

- Stanford White and Charles Follen McKim, who worked in Richardson's office as young men, went on to form McKim, Mead and White and moved into the radically different Beaux - Arts architecture style

- Richardson's great admirer Louis Sullivan adapted Richardson's characteristic lessons of texture, massing, and the expressive language of stone walling, particularly at Chicago's Auditorium Building, and these influences are detectable in the work of Sullivan's own student Frank Lloyd Wright.

- Richardson found sympathetic reception among young Scandinavian architects of the following generation, notably Eliel Saarinen

- The Patrick F. Taylor Library, formerly known as the Howard Memorial Library, was built soon after Richardson's death. It is sometimes called "the only Richardson building located in the South". Residents of New Orleans had wanted an example of Richardson's work, a native son of New Orleans. The office of Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge used a Richardson design which had been submitted and rejected some years earlier for a library in Saginaw, Michigan. This leads some, particularly those in New Orleans, to argue that the building can be said to be by Richardson; the counter argument is that the design was not originally intended for this location and the building was constructed after Richardson's death with no input from the architect beyond the initial design. The library building is currently part of the Ogden Museum of Southern Art.

Although many structures exist in the Romanesque style and some borrow so heavily that they are often mistaken for Richardson designs, several buildings have been built specifically to mimic a single Richardson structure.

- Wellesley Farms Railroad Station - This structure was built by Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge (draftsmen of Richardson) soon after Richardson's death. Although this firm built many stations in Richardson's style, they were specifically penalized for this one because it was so similar to Richardson's Eliot station in Newton, Massachusetts. Eliot station was torn down in the 1950s.

- A railroad station in Orchard Park, New York (near Buffalo), was built in 1911 as a replica of Richardson's Auburndale station in Auburndale, Massachusetts. The original Auburndale station, Richardson's first for the Boston & Albany Railroad and which was described by Henry Russell Hitchcock as "the best he ever built", was torn down in the 1960s during construction of the Massachusetts Turnpike.

- The Old Orange County Courthouse in Santa Ana, California, was completed in 1906 and is heavily influenced by Richardson's designs, bearing a strong resemblance to Richardson's Sever Hall at Harvard.

- Castle Hill Light is a lighthouse in Newport, Rhode Island, which is often attributed to Richardson. Richardson drew a sketch for the lighthouse at that location which may have been the basis for the design, though the actual structure does not include the residence featured in Richardson's sketch.

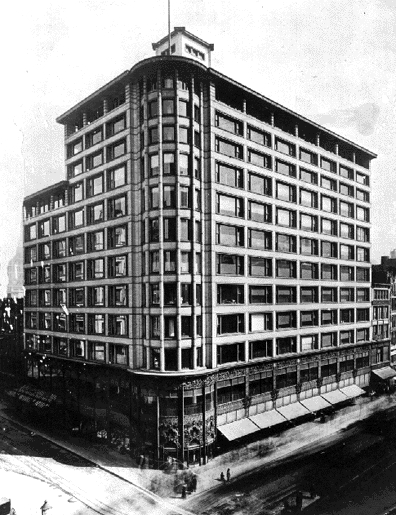

Louis Henri Sullivan (September 3, 1856 – April 14, 1924) was an American architect, and has been called the "father of skyscrapers" and "father of modernism". He is considered by many as the creator of the modern skyscraper, was an influential architect and critic of the Chicago School, was a mentor to Frank Lloyd Wright, and an inspiration to the Chicago group of architects who have come to be known as the Prairie School. Along with Henry Hobson Richardson and Frank Lloyd Wright, Sullivan is one of "the recognized trinity of American architecture".

Louis Sullivan was born to an Irish born father and a Swiss born mother, both of whom had immigrated to the United States in the late 1840s. He grew up living with his grandmother in South Reading (now Wakefield), Massachusetts. Louis spent most of his childhood learning about nature while on his grandparent’s farm. In the later years of his primary education, his experiences varied quite a bit. He would spend a lot of time by himself wandering around Boston. He explored every street looking at the surrounding buildings. This was around the time when he developed his fascination with buildings and he decided he would one day become a structural engineer / architect. While attending high school Sullivan met Moses Woolson, whose teachings made a lasting impression on him, and nurtured him until his death. After graduating from high school, Sullivan studied architecture briefly at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Learning that he could both graduate from high school a year early and pass up the first two years at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology by passing a series of examinations, Sullivan entered MIT at the age of sixteen. After one year of study, he moved to Philadelphia and talked himself into a job with architect Frank Furness.

The Depression of 1873 dried up much of Furness’s work, and he was forced to let Sullivan go. At that point Sullivan moved on to Chicago in 1873 to take part in the building boom following the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. He worked for William LeBaron Jenney, the architect often credited with erecting the first steel frame building. After less than a year with Jenney, Sullivan moved to Paris and studied at the École des Beaux - Arts for a year. Renaissance art inspired Sullivan’s mind, and he was influenced to direct his architecture to emulating Michelangelo's spirit of creation rather than replicating the styles of earlier periods. He returned to Chicago and began work for the firm of Joseph S. Johnston & John Edelman as a draftsman. Johnston & Edleman were commissioned for interior design of the Moody Tabernacle, which was completed by Sullivan. In 1879 Dankmar Adler hired Sullivan; a year later, he became a partner in the firm. This marked the beginning of Sullivan's most productive years. And it was at this firm that Sullivan would deeply influence a young designer named Frank Lloyd Wright, who came to embrace Sullivan's designs and principles as the inspiration for his own work.

Adler and Sullivan initially

achieved fame as theater architects. While most of their theaters were

in Chicago, their fame won commissions as far west as Pueblo, Colorado, and Seattle, Washington (unbuilt). The culminating project of this phase of the firm's history was the 1889 Auditorium Building in

Chicago, an extraordinary mixed use building which included not only a

3000 seat theater, but also a hotel and office building. Adler and

Sullivan reserved the top floor of the tower for their own office. After

1889 the firm became known for their office buildings, particularly the

1891 Wainwright Building in St. Louis and the 1899 Carson Pirie Scott Department Store on

State Street in Chicago, Louis Sullivan is considered by many to be the

first architect to fully imagine and realize a rich architectural

vocabulary for a revolutionary new kind of building: the steel

high rise.

Prior to the late 19th century, the weight of a multistory building had to be supported principally by the strength of its walls. The taller the building, the more strain this placed on the lower sections of the building; since there were clear engineering limits to the weight such "load - bearing" walls could sustain, large designs meant massively thick walls on the ground floors, and definite limits on the building's height.

The development of cheap, versatile steel in the second half of the 19th century changed those rules. America was in the midst of rapid social and economic growth that made for great opportunities in architectural design. A much more urbanized society was forming and the society called out for new, larger buildings. The mass production of steel was the main driving force behind the ability to build skyscrapers during the mid 1880s. As seen with the data below the prices dropped significantly during this period.

Price of Steel at Bessemer Steel Rails from 1867 to 1895 ($/ton)

1867- $166; 1870- $107; 1875- $69; 1880- $68; 1885- $29; 1890- $32; 1895- $32

The people in Midwestern America felt less social pressure to conform to the ways and styles of the architectural past. By assembling a framework of steel girders, architects and builders could suddenly create tall, slender buildings with a strong and relatively delicate steel skeleton. The rest of the building's elements — the walls, floors, ceilings, and windows — were suspended from the steel, which carried the weight. This new way of constructing buildings, so-called "column - frame" construction, pushed them up rather than out. The steel weight - bearing frame allowed not just taller buildings, but permitted much larger windows, which meant more daylight reaching interior spaces. Interior walls became thinner, which created more usable floor space.

Chicago's Monadnock Building (which was not designed by Sullivan) straddles this remarkable moment of transition: the northern half of the building, finished in 1891, is of load - bearing construction, while the southern half, finished only two years later, is column - frame. (While experiments in this new technology were taking place in many cities, Chicago was the crucial laboratory. Industrial capital and civic pride drove a surge of new construction throughout the city's downtown in the wake of the 1871 fire.)

The technical limits of weight - bearing masonry had always imposed formal as well as structural constraints; those constraints were suddenly gone. None of the historical precedents were any help, and this new freedom created a kind of technical and stylistic crisis.

Sullivan was the first to cope with that crisis. He addressed it by embracing the changes that came with the steel frame, creating a grammar of form for the high rise (base, shaft, and pediment), simplifying the appearance of the building by breaking away from historical styles, using his own intricate flora designs, in vertical bands, to draw the eye upwards and emphasize the building's vertical form, and relating the shape of the building to its specific purpose. All this was revolutionary, appealingly honest, and commercially successful.

Louis Sullivan coined the phrase "form ever follows function", which, shortened to "form follows function," would become the great battle cry of modernist architects. This credo, which placed the demands of practical use above aesthetics, would later be taken by influential designers to imply that decorative elements, which architects call "ornament," were superfluous in modern buildings. But Sullivan himself neither thought nor designed along such dogmatic lines during the peak of his career. Indeed, while his buildings could be spare and crisp in their principal masses, he often punctuated their plain surfaces with eruptions of lush Art Nouveau and something like Celtic Revival decorations, usually cast in iron or terra cotta, and ranging from organic forms like vines and ivy, to more geometric designs, and interlace, inspired by his Irish design heritage. Terra cotta is lighter and easier to work with than stone masonry. Sullivan used it in his architecture because it had a malleability that was appropriate for his ornament. Probably the most famous example is the writhing green ironwork that covers the entrance canopies of the Carson Pirie Scott store on South State Street. These ornaments, often executed by the talented younger draftsman in Sullivan's employ, would eventually become Sullivan's trademark; to students of architecture, they are his instantly recognizable signature.

Another signature element of Sullivan's work is the massive, semi - circular arch. Sullivan employed such arches throughout his career — in shaping entrances, in framing windows, or as interior design.

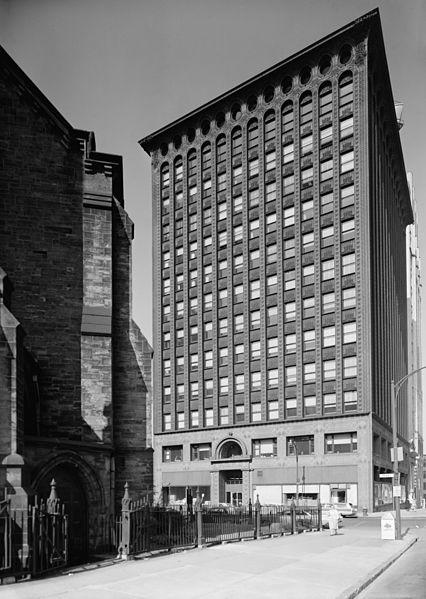

All of these elements can be found in Sullivan's widely admired Guaranty Building, which he designed while partnered with Adler. Completed in 1895, this office building in Buffalo, New York is in the Palazzo style, visibly divided into three "zones" of design: a plain, wide windowed base for the ground level shops; the main office block, with vertical ribbons of masonry rising unimpeded across nine upper floors to emphasize the building's height; and an ornamented cornice perforated by round windows at the roof level, where the building's mechanical units (like the elevator motors) were housed. The cornice crawls with Sullivan's trademark Art Nouveau vines; each ground floor entrance is topped by a semi - circular arch.

Because of Sullivan's remarkable accomplishments in design and construction at such a critical point in architectural history, he has sometimes been described as the "father" of the American skyscraper. In truth, many architects had been building skyscrapers before or contemporarily with Sullivan. Chicago itself was replete with extraordinary designers and builders in the late years of the 19th century, including Sullivan's partner Dankmar Adler, as well as Daniel Burnham, and John Wellborn Root. Root was one of the builders of the Monadnock Building. That and another Root design, the Masonic Temple Tower (both in Chicago), are cited by many as the originators of skyscraper aesthetics of bearing wall and column frame construction respectively.

It

may be that Sullivan's prominence in skyscraper history can be credited

not only to his brilliance, but in some degree to the myth making

skills of his disciple, Frank Lloyd Wright, and to the impact of

Sullivan's own book, The Autobiography of an Idea.

He may also owe some of his legend to the tragic tint of his later

years, which lend this great innovator's story a poignancy which has

captured the imagination of student and historian alike.

In 1890 Sullivan was one of the ten architects, five from the Eastern U.S.

and five from the Western U.S., chosen to build a major structure for

the "White City", the World's Columbian Exposition,

held in Chicago in 1893. Sullivan's massive Transportation Building and

huge arched "Golden Door" stood out as the only forward looking design

in a sea of Beaux - Arts historical copies, and the only multicolored facade in the White City. Sullivan and fair director Daniel Burnham were

vocal about their displeasure with each other. Sullivan was later

(1922) to claim that the fair set the course of American architecture

back "for half a century from its date, if not longer." His was the only building to receive extensive recognition outside America, receiving three medals from the Union Centrale des Arts Decoratifs the following year.

Like all American architects, Adler and Sullivan saw a precipitous decline in their practice with the onset of the Panic of 1893. According to Charles Bebb, who was working in the office at that time, Adler borrowed money to try to keep employees on the payroll. By 1894, however, in the face of continuing financial distress with no relief in sight, Adler and Sullivan dissolved their partnership. The Guaranty Building was considered the last major project of the firm.

By both temperament and connections, Adler had always been the one who brought in new business to the partnership, and after the rupture Sullivan received few large commissions after the Carson Pirie Scott Department Store. He went into a twenty year long financial and emotional decline, beset by a shortage of commissions, chronic financial problems and alcoholism. He obtained a few commissions for small town Midwestern banks, wrote books, and in 1922 appeared as a critic of Raymond Hood's winning entry for the Tribune Tower competition, a steel frame tower dressed in Gothic stonework that Sullivan found a shameful piece of historicism. He and his former understudy Frank Lloyd Wright reconciled in time for Wright to help fund Sullivan's funeral after he died, poor and alone, in a Chicago hotel room on April 14, 1924. He left a wife, Mary Azona Hattabaugh, from whom he was separated; the couple had no children. A modest headstone marks his final resting spot in Graceland Cemetery in Chicago's Uptown neighborhood. Only yards away from his resting place, some of Chicago's lesser known but much wealthier dead are entombed in handsome and distinctive tombs designed by Sullivan himself. A monument was later erected in Sullivan's honor, a few feet from his headstone.

Sullivan's

legacy is contradictory. Some consider him the first modernist. His

forward looking designs clearly anticipate some issues and solutions of

Modernism. However, his embrace of ornament makes his contribution

distinct from the Modern Movement that coalesced in the 1920s and became

known as the "International Style".

To experience Sullivan's built work is to experience the irresistible

appeal of his incredible designs, the vertical bands on the Wainwright

Building, the burst of welcoming Art Nouveau ironwork

on the corner entrance of the Carson Pirie Scott store, the (lost)

terra cotta griffins and porthole windows on the Union Trust building,

the white angels of the Bayard Building. Except for some designs by his long time draftsman George Grant Elmslie, and the occasional tribute to Sullivan such as Schmidt, Garden & Martin's First National Bank in Pueblo, Colorado (built across the street from Adler and Sullivan's Pueblo Opera House), his style is unique. A visit to the preserved Chicago Stock Exchange trading floor, now at The Art Institute of Chicago,

is proof of the immediate and visceral power of the ornament that he

used so selectively. Original drawings and other archival materials from

Sullivan are held by the Ryerson & Burnham Libraries in the Art Institute of Chicago and by the Drawings and Archives Department in the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University. Fragments of Sullivan buildings are also held in many fine art and design museums around the world.

During the postwar era of urban renewal, Sullivan's works fell into disfavor, and many were demolished. In the 1970s growing public concern for these buildings finally resulted in many being saved. The most vocal voice was Richard Nickel, who held protests of demolitions. Nickel and others sometimes rescued decorative elements from condemned buildings, sneaking in during demolition. This practice led to Nickel's death inside Sullivan's Stock Exchange building, when a floor above him collapsed.

Another was the architect Crombie Taylor (1907 – 1991), of Crombie Taylor Associates, who with single - minded determination, led the effort to save the Van Allen Building in Clinton, Iowa, from demolition. Taylor, acting as an aesthetic consultant, had worked on the renovation of the Auditorium Building (now Roosevelt University) in Chicago. When

he read an article about the planned demolition, he uprooted his family

again from their home in Southern California (long after he had left

Chicago, after heading the famous "Institute of Design" - later known as

the Illinois Institute of Technology - IIT in the 1950s and early 1960s)

and moved them to Clinton. With a vision of the destination neighborhood

reminiscent of Oak Park, Illinois, he set about creating a non-profit to save the building, and was successful.