<Back to Index>

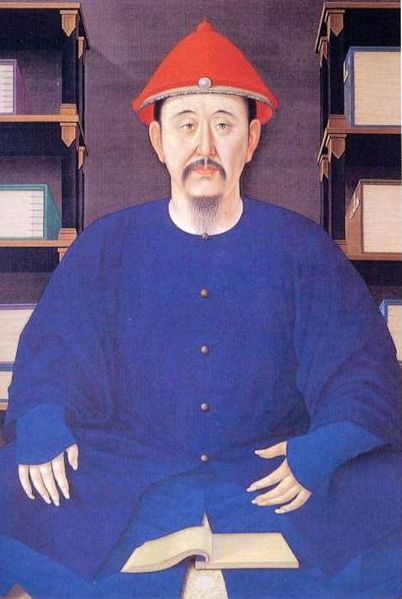

- Emperor of the Qing Dynasty Kangxi, 1654

PAGE SPONSOR

The Kangxi Emperor (Chinese: 康熙帝; temple name: Qīng Shèngzǔ (清聖祖); Manchu: ᡝᠯᡥᡝ ᡨᠠᡳᡶᡳᠨ elhe taifin hūwangdi; Mongolian: Энх-Амгалан хаан, 4 May 1654 – 20 December 1722) was the fourth emperor of the Qing Dynasty, the first to be born on Chinese soil south of the Pass (Beijing) and the second Qing emperor to rule over China proper, from 1661 to 1722.

Kangxi's reign of 61 years makes him the longest reigning Chinese emperor in history (although his grandson, the Qianlong Emperor, had the longest period of de facto power) and one of the longest reigning rulers in the world. However, having ascended the throne at the age of seven, he was not the effective ruler until later, with that role temporarily fulfilled for six years by four regents and his grandmother, the Grand Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang.

Kangxi is considered one of China's greatest emperors. He suppressed the Revolt of the Three Feudatories, forced the Kingdom of Tungning on Taiwan to submit to Qing rule, blocked Tzarist Russia on the Amur River and expanded the empire in the northwest. He also accomplished such literary feats as the compilation of the Kangxi Dictionary.

Kangxi's

reign brought about long term stability and relative wealth after years

of war and chaos. He initiated the period known as the "Prosperous Era

of Kangxi and Qianlong", which lasted for generations after his own

lifetime. By the end of his reign, the Qing Empire controlled all of China proper, Taiwan, Manchuria, part of the Russian Far East (Outer Manchuria), both Inner and Outer Mongolia, Tibet proper, and Joseon Korea as a protectorate.

Born on 4 May 1654 to the Shunzhi Emperor and Empress Xiaokangzhang, Kangxi was originally given the personal name Xuanye (Chinese: 玄燁; Manchu language: ᡥᡳᠣᠸᠠᠨ ᠶᡝᡳ). He was enthroned at the age of seven (or eight by East Asian age reckoning), on 7 February 1661, 12 days after his father's death, although his reign formally began on 18 February 1662, the first day of the following lunar year.

According to some accounts, Shunzhi gave up the throne to Kangxi and became a monk. Several alternative explanations are given for this: one is that it was due to the death of his favorite concubine; another is that he was under the influence of a Buddhist monk. The story goes that Shunzhi did indeed become a monk, but the empress dowager ordered the deletion of the incident from official history records, and replacement with the claim that he died from smallpox.

Before Kangxi came to the throne, Shunzhi had appointed Sonin, Suksaha, Ebilun, and Oboi as regents. Sonin died after his granddaughter became Empress Xiaochengren, leaving Suksaha at odds with Oboi in politics. In a fierce power struggle, Oboi had Suksaha put to death and seized absolute power as sole regent. Kangxi and the rest of the imperial court acquiesced in this arrangement.

In 1669, Kangxi had Oboi arrested with the help of Grand Dowager Empress Xiaozhuang, who had raised him and began taking personal control of the empire. He listed three issues of concern: flood control of the Yellow River; repair of the Grand Canal; the Revolt of the Three Feudatories in

south China. The Grand Empress Dowager influenced him greatly and he

took care of her himself in the months leading up to her death in 1688.

The main army of the Qing Empire, the Eight Banners Army, was in decline under Kangxi. It was smaller than it had been at its peak under Hong Taiji and in the early reign of the Shunzhi Emperor; however, it was larger than in the Yongzheng and Qianlong emperors' reigns. In addition, the Green Standard Army was still powerful with generals such as Tuhai, Fei Yanggu, Zhang Yong, Zhou Peigong, Shi Lang, Mu Zhan, Shun Shike and Wang Jingbao.

The main reason for this decline was a change in system between Kangxi and Qianlong's reigns. Kangxi continued using the traditional military system implemented by his predecessors, which was more efficient and stricter. According to the system, a commander who returned from a battle alone (with all his men dead) would be put to death, and likewise for a foot soldier. This was meant to motivate both commanders and soldiers alike to fight valiantly in war because there was no benefit for the sole survivor in a battle.

By

Qianlong's reign, military commanders had become lax and the training

of the army was deemed less important as compared to during the previous

emperors' reigns. This was because commanders' statuses had become

hereditary; a general gained his position based on the contributions of

his forefathers.

In the spring of 1662, the regents ordered a Great Clearance in southern China to counter a resistance movement started by Ming loyalists under the leadership of Koxinga. This involved the forced migration of entire populations in the coastal regions of inland southern China.

In 1673, the Revolt of the Three Feudatories broke out. Wu Sangui's forces overran most of southwest China and he tried to ally himself with local generals such as Wang Fuchen. Kangxi employed generals such as Zhou Peigong and Tuhai to suppress the rebellion, and also granted clemency to the common people who were caught up in the war. He intended to personally lead the armies to crush the rebels but his subjects advised him against it. The revolt ended with victory for Qing forces in 1681.

In 1683, the Kingdom of Tungning was defeated by Qing naval forces under the command of admiral Shi Lang at the Battle of Penghu. Zheng Keshuang, ruler of Tungning, surrendered a few days later, and Taiwan was annexed by the Qing Empire. Soon afterwards, the coastal regions of southern China were ordered to be repopulated. In addition, to encourage settlers, the Qing government granted financial incentives to families that settled there.

In 1673, Kangxi's government helped to mediate a truce in the Trịnh – Nguyễn War in Vietnam,

which had been ongoing for 45 years since 1627. The peace treaty that

was signed between the conflicting parties lasted for 101 years until

1774.

In the 1650s, the Qing Empire engaged the Russian Empire in a series of border conflicts along the Amur River region, which concluded with victory for the Qing side. After the Siege of Albazin, he gained control of the area.

The Russians invaded the northern frontier again in the 1680s. After a series of battles and negotiations, both sides signed the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689, in which a border was fixed, and the Amur River valley given to the Qing Empire.

In 1675, Burni of the Chahar Mongols started a rebellion against the Qing Empire. The revolt was crushed within two months and the Chahars were incorporated in the Manchu Eight Banners.

The Khalkha Mongols had preserved their independence, and only paid tribute to the Qing Empire. However, a conflict between the houses of Tümen Jasagtu Khan and Tösheetü Khan led to a dispute between the Khalkha and the Dzungars over the influence of Tibetan Buddhism. In 1688, as the Khalkhas were fighting wars with Russian Cossacks in the north of their territory, the Dzungar chief, Galdan Boshugtu Khan, attacked the Khalkha from the west and invaded their territory. The Khalkha royal families and the first Jebtsundamba Khutuktu crossed the Gobi Desert and

sought help from the Qing Empire in return for submission to Qing

authority. In 1690, the Dzungars and Qing forces clashed at the Battle

of Ulaan Butun in Inner Mongolia, in which the Qing eventually emerged as the victor.

In 1696, Kangxi personally led three armies, totaling 80,000 in strength, in a campaign against the Dzungars. The western section of the Qing army defeated Galdan's forces at the Battle of Jao Modo and Galdan died in the following year.

The Dzungars continued to threaten the Qing Empire and invaded Tibet in 1717. In response to the deposition of the Dalai Lama and his replacement with Lha-bzang Khan in 1706, they took control of Lhasa with

a 6,000 strong army and removed Lha-bzang from power. They held on to

the city for two years and defeated a Qing army in 1718. Lhasa was not

retaken by the Qing Empire until 1720.

The contents of the national treasury during Kangxi's reign were:

- 1668 (7th year of Kangxi): 14,930,000 taels

- 1692: 27,385,631 taels

- 1702-1709: approximately 50,000,000 taels with little variation during this period

- 1710: 45,880,000 taels

- 1718: 44,319,033 taels

- 1720: 39,317,103 taels

- 1721 (60th year of Kangxi, second last of his reign): 32,622,421 taels

The

reasons for the declining trend in the later years of Kangxi's reign

were a huge expenditure on military campaigns and an increase in

corruption. To fix the problem, Kangxi gave Prince Yong (the future Yongzheng Emperor) advice on how to make the economy more efficient.

During his reign, Kangxi ordered the compilation of a dictionary of Chinese characters, which became known as the Kangxi Dictionary. This was seen as an attempt by Kangxi to gain support from the Han Chinese scholar - bureaucrats, as many of them initially refused to serve him and remained loyal to the Ming Dynasty. However, by persuading the scholars to work on the dictionary without asking them to formally serve the Qing imperial court, Kangxi led them to gradually taking on greater responsibilities until they were assuming the duties of state officials.

In 1705, on Kangxi's order, a compilation of Tang poetry, the Quantangshi, was produced.

Kangxi also was interested in Western technology and wanted to import them to China. This was done through Jesuit missionaries, such as Ferdinand Verbiest, whom Kangxi frequently summoned for meetings, or Karel Slavíček, who made the first precise map of Beijing on Kangxi's order.

From 1711 to 1723, Matteo Ripa, an Italian priest sent to China by the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples, worked as a painter and copper engraver at the Qing court. In 1723, he returned to Naples from China with four young Chinese Christians, in order to groom them to become priests and send them back to China as missionaries. This marked the beginning of the Collegio dei Cinesi, sanctioned by Pope Clement XII to help the propagation of Christianity in China. This Chinese Institute was the first school of Sinology in Europe, which would later develop to become the Instituto Orientale and the present day Naples Eastern University.

Kangxi was also the first Chinese emperor to play a western musical instrument. He employed Karel Slavíček as court musician. Slavíček was playing Spinet; later Kangxi would play on it himself. He also invented a Chinese calendar.

In the early decades of Kangxi's reign, Jesuits played a large role in the imperial court. With their knowledge of astronomy, they ran the imperial observatory. Jean - François Gerbillon and Thomas Pereira served as translators for the negotiations of the Treaty of Nerchinsk. Kangxi was grateful to the Jesuits for their contributions, the many languages they could interpret, and the innovations they offered his military in gun manufacturing and artillery, the latter of which enabled the Qing Empire to conquer the Kingdom of Tungning.

Kangxi was also fond of the Jesuits' respectful and unobtrusive manner; they spoke the Chinese language well, and wore the silk robes of the elite. In 1692, when Fr. Thomas Pereira requested tolerance for Christianity, Kangxi was willing to oblige, and issued the Edict of Toleration, which recognized Catholicism, barred attacks on their churches, and legalized their missions and the practice of Christianity by the Chinese people.

However, controversy arose over whether Chinese Christians could still take part in traditional Confucian ceremonies and ancestor worship, with the Jesuits arguing for tolerance and the Dominicans taking a hard line against foreign "idolatry". The Dominican position won the support of Pope Clement XI, who in 1705 sent Charles - Thomas Maillard De Tournon as his representative to Kangxi, to communicate the ban on Chinese rites. On 19 March 1715, Pope Clement XI issued the papal bull Ex illa die, which officially condemned Chinese rites.

In response, Kangxi officially forbade Christian missions in China, as they were "causing trouble".

The matter of Kangxi's will is one of the "Four Greatest Mysteries of the Qing Dynasty". To this day, whom Kangxi chose as his successor is still a topic of debate amongst historians: on the face of things, he chose Yinzhen, the fourth prince, who later became the Yongzheng Emperor, and indeed there is strong evidence that this is correct. However many have claimed that Yinzhen forged the will, and that in reality the 14th prince Yinti, had been chosen as the successor.

Kangxi's first spouse, Empress Xiaochengren, gave birth to his second surviving son Yinreng, who at the age of two was named crown prince, a Han Chinese custom, to ensure stability during a time of chaos in the south. Although Kangxi left the education of several of his sons to others, he personally oversaw the upbringing of Yinreng, intending to groom him into a perfect heir. Yinreng was tutored by the mandarin Wang Shan, who remained devoted to him, and spent the later years of his life trying to persuade Kangxi to restore Yinreng as the crown prince.

Yinreng did not prove himself to be worthy of the succession despite his father showing favoritism towards him. He was said to have beaten and killed his subordinates, and was alleged to have had sexual relations with one of his father's concubines, which was deemed as incest and a capital offence. Yinreng also purchased young children from Jiangsu to satisfy his pedophiliac pleasure. In addition, Yinreng's supporters, led by Songgotu, gradually formed a "Crown Prince Party" (太子黨), that aimed to help Yinreng get the throne as soon as possible, even if it meant using unlawful methods.

Over the years, Kangxi kept constant watch over Yinreng and became aware of his son's many flaws, while their relationship gradually deteriorated. In 1707, Kangxi decided that he could no longer tolerate Yinreng's behavior, which he partially mentioned in the imperial edict as "too embarrassing to be spoken of", and decided to strip Yinreng off his position as crown prince. Kangxi placed his oldest surviving son, Yinshi, in charge of overseeing Yinreng's house arrest. However, Yinshi attempted to sabotage Yinreng numerous times and requested for his father to order Yinreng's execution. Kangxi was enraged and stripped Yinshi of his titles. Kangxi advised his subjects to stop debating about the succession issue, and despite attempts to reduce rumors and speculation as to who the new crown prince might be, the imperial court's daily activities were disrupted. Apart from that, Yinshi's actions also caused Kangxi to suspect that Yinreng might have been framed, hence Kangxi restored Yinreng as crown prince in 1709, with the support of the 4th and 13th princes, and on the excuse that Yinreng had previously acted under the influence of mental illness.

In

1712, during Kangxi's last inspection tour to the south, Yinreng, who

was put in charge of state affairs during his father's absence, tried to

vie for power again with his supporters. He allowed an attempt at

forcing Kangxi to abdicate when his father returned to Beijing. However, Kangxi received news of the planned coup d'etat,

and was so angry that he deposed Yinreng and placed him under house

arrest again. After the incident, Kangxi announced that he would not

appoint any of his sons as crown prince for the remainder of his reign.

He stated that he would place his Imperial Valedictory Will inside a box

in the Palace of Heavenly Purity, which will only be opened after his death.

Following the deposition of the crown prince, Kangxi implemented groundbreaking changes in the political landscape. The 13th prince, Yinxiang, was placed under house arrest as well for cooperating with Yinreng. The eighth prince Yinsi was stripped off all his titles and only had them restored years later. The 14th prince Yinti, whom many considered to be the most likely candidate to succeed Kangxi, was sent on a military campaign during the political conflict. Yinsi, along with the ninth and tenth princes, Yintang and Yin'e, pledged their support to Yinti.

In

the evening of 20 December 1722 before his death, Kangxi called seven

of his sons to assemble at his bedside. They were the third, fourth,

eight, ninth, tenth, 16th and 17th princes. After Kangxi died, Longkodo announced

that Kangxi had selected the fourth prince, Yinzhen, as the new

emperor. Yinzhen ascended to the throne and became known as the Yongzheng Emperor. Kangxi was entombed at the Eastern Tombs in Zunhua, Hebei.

Kangxi was the great consolidator of the Qing Dynasty. The transition from the Ming Dynasty to the Qing was a cataclysm whose central event was the fall of the capital Beijing to the invading Manchus in 1644, and the installation of the five year old Shunzhi Emperor on their throne. By 1661, when Shunzhi died and was succeeded by Kangxi, the Qing conquest was almost complete and the leading Manchus were already adopting Chinese ways including Confucian ideology. Kangxi completed the conquest, suppressed all significant military threats and revived the ancient central government system with important modifications.

Kangxi was an inveterate workaholic, rising early and retiring late, reading and responding to numerous memorials every day, conferring with his councilors and giving audiences – and this was in normal times; in wartime, he might be reading memorials from the war front until after midnight or even, as with the Dzungar conflict, away on campaign in person.

Kangxi devised a system of communication that circumvented the scholar - bureaucrats, who had a tendency to usurp the power of the emperor. This Palace Memorial System involved the transfer of secret messages between him and trusted officials in the provinces, where the messages were contained in locked boxes that only he and the official had access to. This started as a system for receiving uncensored extreme weather reports, which the emperor regarded as divine comments on his rule. However, it soon evolved into a general purpose secret "news channel". Out of this emerged a Grand Council, which dealt with extraordinary, especially military, events. The council was chaired by the emperor and manned by his more elevated Han Chinese household staff. From this council, the mandarin civil servants were excluded – they were left only with routine administration.

Kangxi managed to seduce the Confucian intelligentsia into co-operating with the Qing government, despite their deep reservations about Manchu rule, by encouraging them to sit the traditional civil service examinations, become mandarins and subsequently to compose lavishly conceived works of literature such the History of Ming, the Kangxi Dictionary, a phrase dictionary, a vast encyclopedia and an even vaster compilation of Chinese literature. On a personal level, Kangxi was a cultivated man, steeped in Confucian learning.

In the one military campaign in which he actively participated, against the Dzungar Mongols, Kangxi showed himself an effective military commander. According to Finer, Kangxi's own written reflections allow one to experience "how intimate and caring was his communion with the rank - and - file, how discriminating and yet masterful his relationship with his generals".

As

a result of the scaling down of hostilities as peace returned to China

after the Manchu conquest, and also as a result of the ensuing rapid

increase of population, land cultivation and therefore tax revenues

based on agriculture, Kangxi was able first to make tax remissions, then

in 1712 to freeze the land tax and corvée altogether, without embarrassing the state treasury.