<Back to Index>

- Physician Zabdiel Boylston, 1679

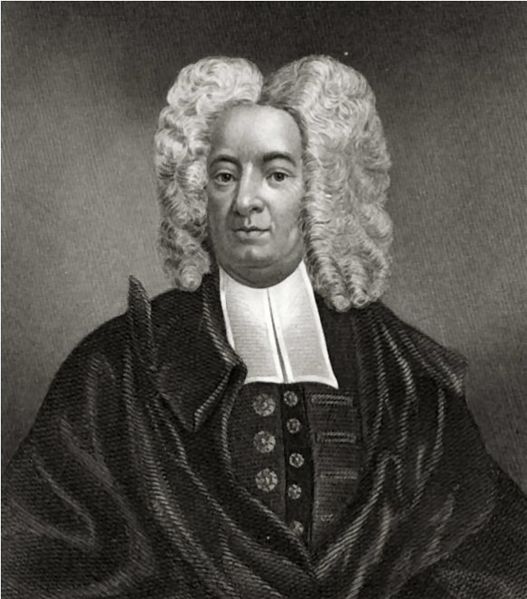

- Minister and Author Cotton Mather, 1663

PAGE SPONSOR

Zabdiel Boylston, FRS (1679 in Brookline, Massachusetts – March 2, 1766) was a physician in the Boston area.

He apprenticed with his father, an English surgeon named Thomas

Boylston. He also studied under the Boston physician Dr. Cutler, never

attending a formal medical school (the first medical school in North America was not founded until 1765).

Boylston is known for holding several "firsts" for an American born physician: He performed the first surgical operation by an American physician, the first removal of gall bladder stones in 1710, and was the first to remove a breast tumor in 1718.

He was a great uncle of both president John Adams, and philanthropist Ward Nicholas Boylston.

During a smallpox outbreak in 1721 in Boston, he inoculated about 248 people by applying pus from a smallpox sore to a small wound on the subjects, a method said to have been previously used in Africa. Initially, he used the method on two slaves and his own son. This was the first introduction of inoculations to the United States. An African slave named Onesimus taught the idea to Cotton Mather, the influential New England Puritan minister.

His

method was initially met by hostility and outright violence from some

religious groups and most other physicians, and he was arrested for a

short period of time for it (he was later released with the promise not

to inoculate without government permission). In 1724, Boylston traveled

to London, where he published his results as Historical Account of the Small - Pox Inoculated in New England, and became a fellow of the Royal Society two years later. Afterward, he returned to Boston.

Cotton Mather, FRS (February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728; A.B. 1678, Harvard College; A.M. 1681, honorary doctorate 1710, University of Glasgow) was a socially and politically influential New England Puritan minister, prolific author and pamphleteer; he is often remembered for his role in the Salem witch trials. He was the son of Increase Mather, and grandson of both John Cotton and Richard Mather, all also prominent Puritan ministers.

Mather was named after his maternal grandfather, John Cotton. He attended Boston Latin School, where his name was posthumously added to its Hall of Fame, and graduated from Harvard in 1678 at age 15. After completing his post - graduate work, he joined his father as assistant pastor of Boston's original North Church. In 1685 Mather assumed full responsibilities as pastor at the Church.

Cotton Mather wrote more than 450 books and pamphlets, and his ubiquitous literary works made him one of the most influential religious leaders in America. Mather set the moral tone in the colonies, and sounded the call for second and third generation Puritans, whose parents had left England for the New England colonies of North America, to return to the theological roots of Puritanism.

The most important of these, Magnalia Christi Americana (1702), comprises seven distinct books, many of which depict biographical and historical narratives to which later American writers, such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Elizabeth Drew Stoddard, and Harriet Beecher Stowe, would look in describing the cultural significance of New England for later generations after the American Revolution. Mather's text thus is one of the more important documents in American history, because it reflects a particular tradition of seeing and understanding the significance of place. Mather, as a Puritan thinker and social conservative, drew on the language of the Bible to speak to contemporary audiences. In particular, Mather's review of the American experiment sought to explain signs of his time and the types of individuals drawn to the colonies as predicting the success of the venture. From his religious training, Mather viewed the importance of texts for elaborating meaning and for bridging different moments of history — linking, for instance, the Biblical stories of Noah and Abraham with the arrival of such eminent leaders as John Eliot; John Winthrop; and his own father, Increase Mather.

Through his writings the intellectual and physical struggles of first through third generation Puritans created an elevated appraisal in the minds of Americans about its appointed place among other nations. The unease and self - deception that characterized that period of colonial history would be revisited in many forms at political and social moments of crisis (such as the Salem witch trials, which coincided with frontier warfare and economic competition among Indians and French and other European settlers) and during lengthy periods of cultural definition (such as the American Renaissance of the late 18th and early 19th century literary, visual, and architectural movements, which sought to capitalize on unique American identities).

Highly

influential because of his prolific writing, Mather was a force to be

reckoned with in secular, as well as in spiritual, matters. After the

fall of James II of England, in 1688, Mather was among the leaders of the successful revolt against James's governor of the consolidated Dominion of New England, Sir Edmund Andros.

Mather also influenced early American science. In 1716, because of observations of corn varieties, he conducted one of the first recorded experiments with plant hybridization. This observation was memorialized in a letter to a friend:

- My friend planted a row of Indian corn that was colored red and blue; the rest of the field being planted with yellow, which is the most usual color. To the windward side this red and blue so infected three or four rows as to communicate the same color unto them; and part of ye fifth and some of ye sixth. But to the leeward side, no less than seven or eight rows had ye same color communicated unto them; and some small impressions were made on those that were yet further off.

Of Mather's three wives and 15 children, only his last wife and two children survived him. Mather was buried on Copp's Hill, near Old North Church.

Cotton Mather was not known for writing in a neutral, unbiased perspective. Many, if not all, of his writings had bits and pieces of his own personal life in them or were written for personal reasons. According to literary historian Sacvan Bercovitch:

"Few puritans more loudly decried the bosom serpent of egotism than did Cotton Mather; none more clearly exemplified it. Explicitly or implicitly, he projects himself everywhere in his writings. In the most direct compensatory sense, he does so by using literature as a means of personal redress. He tells us that he composed his discussions of the family to bless his own, his essays on the riches of Christ to repay his benefactors, his tracts on morality to convert his enemies, his funeral discourses to console himself for the loss of a child, wife, or friend".

A huge influence throughout Mather’s career was Robert Boyle.

While coming to terms with who he was, Mather read Robert Boyle’s book

“The Usefulness of Experimental Natural Philosophy.” Mather read Boyle’s

work closely throughout the 1680s and his early works on science and

religion borrowed greatly from it. He even uses almost identical

language to Boyle.

Cotton

Mather's relationship with his well known father, Increase Mather, was

often a strained and difficult one. Increase Mather was a pastor of the

Old North Church and led an accomplished life that Cotton was determined

to live up to. Despite Cotton Mather's efforts, he never became quite

as well known and successful in politics as his father. He did surpass

his father's talents as a writer, writing over 400 books. One of the

most public displays of their strained relationship appeared during the

Salem Witch Trials. Despite the fact that Increase Mather did not

support the trials, Cotton Mather documented them.

The practice of smallpox inoculation (as opposed to the later practice of vaccination) was developed possibly in 8th century India or 10th Century China. Spreading its reach in seventeenth century Turkey, inoculation or, rather, variolation, involved infecting a person through a cut in the skin with exudate from a patient with a relatively mild case of smallpox (variola), in order to bring about a manageable and recoverable infection that will provide later immunity.

By

the beginning of the eighteenth century, the Royal Society in England

was discussing the practice of inoculation, and the smallpox epidemic in

1713 spurred further interest. It was not until 1721, however, that England recorded its first case of inoculation.

Smallpox was a serious threat in colonial America, most devastating to Native Americans, but also to Anglo - American settlers. New England suffered smallpox epidemics in 1677, 1689 – 90, and 1702. It was highly contagious, and mortality could reach as high as 30 percent or more.

Boston

had been plagued by smallpox outbreaks in 1690 and 1702. During this

era, public authorities in Massachusetts dealt with the threat primarily

by means of quarantine. Incoming ships were quarantined in Boston

harbor, and any smallpox patients in town were held under guard or in a

"pesthouse."

In 1706 a slave, Onesimus, explained to Cotton Mather how he had been inoculated as a child in Africa. Mather was fascinated by the idea. By July 1716, Mather had read an endorsement of inoculation by Dr. Emanuel Timonius of Constantinople in the Philosophical Transactions. Mather then declared, in a letter to Dr. John Woodward of Gresham College in London, that he planned to press Boston's doctors to adopt the practice of inoculation should smallpox reach the colony again.

By 1721, a whole generation of young Bostonians was vulnerable and memories of the last epidemic's horrors had by and large disappeared. On April 22 of that year, the HMS Seahorse arrived from the West Indies carrying smallpox on board. Despite attempts to protect the town through quarantine, eight known cases of smallpox appeared in Boston by May 27, and by mid June, the disease was spreading at an alarming rate. As a new wave of smallpox hit the area and continued to spread, many residents fled to outlying rural settlements. The combination of exodus, quarantine, and outside traders' fears disrupted business in the capital of the Bay Colony for weeks. Guards were stationed at the House of Representatives to keep Bostonians from entering without special permission. The death toll reached 101 in September, and the Selectmen, powerless to stop it, "severely limited the length of time funeral bells could toll." As one response, legislators delegated a thousand pounds from the treasury to help the people who, under these conditions, could no longer support their families.

On June 6, 1721, Mather sent an abstract of reports on inoculation by Timonius and Jacobus Pylarinus to local physicians, urging them to consult about the matter. He received no response. Next, Mather pleaded his case to Dr. Zabdiel Boylston, who tried the procedure on his only son and two slaves — one grown and one a boy. All recovered in about a week. Boylston inoculated seven more people by mid July.

The

epidemic peaked in October 1721, with 411 deaths; by February 26, 1722,

Boston was, once again, free of smallpox. The total number of cases

since April 1721 came to 5,889, with 844 deaths — more than three

quarters

of all the deaths in Boston during 1721. Meanwhile, Dr. Boylston had inoculated 242 people, with only six resulting in death.

Boylston and Mather's inoculation crusade "raised a horrid Clamour" amongst the people of Boston. Both Boylston and Mather were "Object[s] of their Fury; their furious Obloquies and Invectives," which Mather acknowledges in his diary. Boston's Selectmen, consulting a doctor who claimed that the practice caused many deaths and only spread the infection, forbade Boylston from performing it again.

The New England Courant published writers who opposed the practice. The editorial stance was that the Boston populace feared that inoculation spread, rather than prevented, the disease; however, some historians, notably H.W. Brands, have argued that this position was a result of editor - in - chief James Franklin's (Benjamin Franklin's brother) contrarian positions.

Public

discourse ranged in tone from organized arguments by tobacconist and

medical practitioner John Williams, who posited that "several arguments

proving that inoculating the smallpox is not contained in the law of

Physick, either natural or divine, and therefore unlawful," to more slanderous attacks, such as those put forth in a pamphlet by Dr. William Douglass of Boston entitled The Abuses and Scandals of Some Late Pamphlets in Favour of Inoculation of the Small Pox (1721),

on the qualifications of inoculation's proponents. (Douglass was

exceptional at the time for holding a medical degree from Europe.) At

the extreme, in November 1721, someone hurled a lighted grenade into

Cotton Mather's house.

Several opponents of smallpox inoculation, among them John Williams, stated that there were only two laws of physick (medicine): sympathy and antipathy. In his estimation, inoculation was neither a sympathy toward a wound or a disease, or an antipathy toward one, but the creation of one. For this reason, its practice violated the natural laws of medicine, transforming health care practitioners into those who harm rather than heal.

As with many colonists, Williams' Puritan beliefs were enmeshed in every aspect of his life, and he used the Bible to state his case. He quoted Matthew 9:12 when Jesus said: "It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick."

In contrast, Dr. William Douglass proposed a more secular argument against inoculation, stressing the importance of reason over passion and urging the public to be pragmatic in their choices. In addition, he demanded that ministers leave the practice of medicine to physicians, and not meddle in areas where they lacked expertise. According to Douglass, smallpox inoculation was "a medical experiment of consequence," one not to be undertaken lightly. He believed that not all learned individuals were qualified to doctor others, and while ministers took on several roles in the early years of the colony, including that of caring for the sick, they were now expected to stay out of state and civil affairs.

Douglass also felt that inoculation caused more deaths than it prevented. The only reason Cotton Mather had success in it, he said, was because Mather had used it on children, who are naturally more resilient. Douglass vowed to always speak out against "the wickedness of spreading infection."

Speak

out he did: "The battle between these two prestigious adversaries

[Douglass and Mather] lasted far longer than the epidemic itself, and

the literature accompanying the controversy was both vast and venomous." In the end, Douglass grew to accept inoculation, but he stood his ground on the need for professional standards.

Puritan principles were core to the religious arguments against inoculation. They believed that they were "elected" by God to establish a godly nation in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. As such, the notion of God’s will being evident in their daily life was paramount, and they strove to accept every affliction as proof of God's special interest in their affairs.

God's authority was absolute, and Williams questioned whether the smallpox "is not one of the strange works of God; and whether inoculation of it be not a fighting with the most High." He also asked his readers if the smallpox epidemic may have been given to them by God as "punishment for sin," and warned that attempting to shield themselves from God's fury (via inoculation), would only serve to "provoke him more." The Puritans found meaning in affliction, and they did not yet know why God was showing them disfavor through smallpox. Not to address their errant ways before attempting a cure could set them back in their "errand."

Many Puritans believed that creating a wound and inserting poison was doing violence and therefore was antithetical to the healing art. They grappled with adhering to the Ten Commandments, with being proper church members and good caring neighbors. The apparent contradiction between harming or murdering a neighbor through inoculation and the Sixth Commandment -- "thou shalt not kill" -- seemed insoluble and hence stood as one of thee main objections against the procedure.

Williams

maintained that because the subject of inoculation could not be found

in the Bible, it was not the will of God, and therefore "unlawful." He also explained that inoculation violated The Golden Rule,

because if one neighbor voluntarily infected another with disease, he

was not doing unto others as he would have done to him. With the Bible

as the Puritans’ source for all decision making, lack of scriptural

evidence concerned many, and Williams vocally scorned Rev. Mather for

not being able to reference an inoculation edict directly from the

Bible.

With the smallpox epidemic catching speed and racking up a staggering death toll, a solution to the crisis was becoming more urgently needed by the day. The use of quarantine and various other efforts, such as balancing the body's humors, did not slow the disease's spread. As news rolled in from town to town and correspondence arrived from overseas, reports of horrific stories of suffering and loss due to smallpox stirred mass panic among the people. "By circa 1700, smallpox had become among the most devastating of epidemic diseases circulating in the Atlantic world."

Cotton Mather strongly challenged the perception that inoculation was against the will of God and argued that the procedure was not outside of Puritan principles. He wrote that "whether a Christian may not employ this Medicine (let the matter of it be what it will) and humbly give Thanks to God’s good Providence in discovering of it to a miserable World; and humbly look up to His Good Providence (as we do in the use of any other Medicine) It may seem strange, that any wise Christian cannot answer it. And how strangely do Men that call themselves Physicians betray their Anatomy, and their Philosophy, as well as their Divinity in their invectives against this Practice?" The Puritan minister began to embrace the sentiment that smallpox was an inevitability for anyone, both the good and the wicked, yet God had provided them with the means to save themselves. Mather reported that, from his view, "none that have used it ever died of the Small Pox, tho at the same time, it were so malignant, that at least half the People died, that were infected With it in the Common way."

The practice of smallpox inoculation was eventually accepted by the general population due to first hand experiences and personal relationships. Although many were initially wary of the concept, it was because people were able to witness the procedure's consistently positive results, within their own community of ordinary citizens, that it became widely utilized and supported. One important change in the practice after 1721 was regulated quarantine of inoculees.

Inoculation visibly and directly aided man's control of the disease, the level of infection, mortality rates and the spreading of the epidemic. Planned inoculation led to better observation of the body's responses and allowed people the ability to time the onset of the pox and control the disease's intensity. For example, by inoculating in the months of milder climate, one had a better chance of fighting the infection and becoming immune instead of the alternative: natural exposure to the disease during harsher weather, when the body's defenses were already challenged.

Additionally,

by the 1750s, innovations and experience with inoculation focused on

better insertion of pox fluid and preparation of body to withstand the

disease. By controlling the point and time of infection, bodies could be

conditioned to optimal state before contracting smallpox, therefore

providing a better opportunity to fight and achieve immunity. Dependent

upon a person's constitution, by adhering to a specific diet or purging,

one could physically handle the infection more successfully. It was

also discovered that inoculation produced less scarring and physical

defects than a common, naturally contracted case.

Although Cotton Mather and Dr. Boylston were able to demonstrate the efficacy of the practice, the debate over inoculation would continue even beyond the epidemic of 1721 - 22. After overcoming considerable difficulty and achieving notable success, Boylston traveled to London in 1724 where he published his results and was elected to the Royal Society in 1726.

The responses of the Boston clergymen to the reproaches put forth by the anti - inoculation camp highlighted seminal changes the Puritan church was undergoing at the time. By prescribing recent advances in medicine, the Boston ministers modified the doctrine of theological pathogenesis in an attempt to maintain the old order according to which it was the clergy’s duty and privilege to interpret illnesses and their cures. However, the contradiction of simultaneously upholding tradition and embracing innovations was impossible to resolve and, as a consequence, the clergy continued to lose influence over secular affairs in eighteenth century New England.

In

the end, lives were saved by inoculation, and the epidemic was halted.

Even today, the procedure is credited with ending the devastation caused

by the early epidemics, and vaccination, in many ways an updated and

modernized form of the procedure, continues to be recommended by the Centers for Disease Control for

at - risk populations, such as potential victims of bioterrorism, and

research scientists who work with surviving strains of the virus.

A friend of a number of the judges charged with hearing the Salem witch trials, Mather admitted the use of spectral evidence ("The Devil in New England") but warned that, though it might serve as evidence to begin investigations, it should not be heard in court as evidence to decide a case. Despite this, he later wrote in defense of those conducting the trials, stating:

- "If in the midst of the many Dissatisfaction among us, the publication of these Trials may promote such a pious Thankfulness unto God, for Justice being so far executed among us, I shall Re-joyce that God is Glorified..." - Wonders of the Invisible World.

17th century New Englanders perceived themselves abnormally susceptible to the Devil’s influence. The idea that New Englanders now occupied the Devil’s land established this fear. In their mind it would only be natural for the Devil to fight back against the pious invaders. Cotton Mather shared this general concern; and combined with New England’s lack of piety, Mather feared divine retribution. English writers, who shared Mather’s fears, cited evidence of divine actions to restore the flock.

In 1681 a conference of ministers met to discuss how to rectify the lack of faith. In an effort to combat the lack of piety, Cotton Mather considered it his duty to observe and record illustrious providences. Cotton Mather’s first action related to the Salem Witch Trials was the publication of his 1684 essay Illustrious Providences. Mather, being an ecclesiastical man, believed in the spiritual side of the world and attempted to prove its existence with stories of sea rescues, strange apparitions and witchcraft. Mather aimed to combat materialism in New England.

Such was the social climate of New England when the Goodwin children received a strange illness. Mather, seeing an opportunity to explore the spiritual world, attempted to treat the children with fasting and prayer. After treating the children of the Goodwin family, Mather wrote Memorable Providences, a detailed account of the illness. In January 1692 Abigail Williams and Betty Parris had a similar illness to the Goodwin children; and Mather emerged as an important figure in the Salem Witch trials. Even though Mather never presided in the jury, he exhibited great influence over the witch trials. On May 31, 1692, Mather sent a letter Return of the Several Ministers,to the trial. This article advised the judges to limit the use of Spectral evidence, and recommended the release of confessed criminals.

Wonders of the Invisible World, describing

the Salem Witch Trials, is one of Cotton Mather's best known books, and

the witch trials themselves are what Mather is well known for. One of

the main reasons that Mather wrote about the witch trials was that he

believed it would "encourage a spiritual awakening in the face of

widespread religious complacency".

Critics of Cotton Mather assert that he caused the trials because of his 1688 publication Remarkable Providences, and attempted to revive the trial with his 1692 book Wonders of the Invisible World, and in general encouraged witch hunting zeal. Others have stated, "His own reputation for veracity on the reality of witchcraft prayed, 'for a good issue.'" Charles Upham mentions Mather called accused witch Martha Carrier a rampant hag. The critical evidence of Mather’s zealous behavior comes later, during the trial execution of George Burroughs {Harvard Class of 1670}. Upham gives the Robert Calef account of the execution of Mr. Burroughs; it is this:

Mr. Burroughs was carried in a cart with others, through the streets of Salem, to execution. When he was upon the ladder, he made a speech for the clearing of his innocency, with such solemn and serious expressions as were to the admiration of all present. His prayer (which he concluded by repeating the Lord’s Prayer) was so well worded, and uttered with such composedness as such fervency of spirit, as was very affecting, and drew tears from many, so that if seemed to some that the spectators would hinder the execution. The accusers said the black man stood and dictated to him. As soon as he was turned off, Mr. Cotton Mather, being mounted upon a horse, addressed himself to the people, partly to declare that he (Mr. Burroughs) was no ordained minister, partly to possess the people of his guilt, saying that the devil often had been transformed into the angel of light… When he [Mr. Burroughs] was cut down, he was dragged by a halter to a hole, or grave, between the rocks, about two feet deep; his shirt and breeches being pulled off, and an old pair of trousers of one executed put on his lower parts: he was so put in, together with Willard and Carrier, that one of his hands, and his chin, and a foot of one of them, was left uncovered.

The second issue with Cotton Mather was his influence in construction of the court for the trials. Sir William Phips, governor of the newly chartered Province of Massachusetts Bay, appointed his lieutenant governor, William Stoughton, as head of a special witchcraft tribunal and then as chief justice of the colonial courts, where he presided over the witch trials. According to Bancroft, Mather had been influential in gaining politically unpopular Stoughton his appointment as lieutenant governor under Phips by appealing to his politically powerful father, Increase Mather. “Intercession had been made by Cotton Mather for the advancement of William Stoughton, a man of cold affections, proud, self - willed and covetous of distinction.” Apparently Mather saw in Stoughton an ally for church related matters. Bancroft quotes Mather’s reaction to Stoughton's appointment as follows:

“The time for a favor is come,” exulted Cotton Mather; “Yea, the set time is come.

Bancroft also noted that Mather considered witches "among the poor, and vile, and ragged beggars upon Earth," and Bancroft asserts that Mather considered the people against the witch trials to be witch advocates.

Chadwick Hansen’s Witchcraft at Salem, published in 1969, defined Mather as a positive influence on the Salem Trials. Hansen considered Mather's handling of the Goodwin Children to be sane and temperate. Hansen also noted that Mather was more concerned with helping the affected children than witch hunting. Mather treated the affected children through prayer and fasting.

Mather also tried to convert accused witch Goodwife Glover after she was accused of practicing witchcraft on the Goodwin children. Most interestingly, and out of character with the previous depictions of Mather, was Mather’s decision not to tell the community of the others whom Goodwife Clover claimed practiced witch craft. Lastly, Hansen claimed Mather acted as a moderating influence in the trials by opposing the death penalty for lesser criminals, such as Tituba and Dorcas Good. Hansen also notes that the negative impressions of Cotton Mather stem from his defense of the trials in Wonders of the Invisible World. Mather became the chief defender of the trial, which diminished accounts of his earlier actions as a moderate influence.

Some

historians who have examined the life of Cotton Mather after Chadwick

Hansen’s book share his view of Cotton Mather. For instance, Bernard

Rosenthal noted that Mather often gets portrayed as the rabid witch

hunter. Rosenthal also described Mather’s guilt about his inability to restrain the judges during the trial. Larry

Gregg highlights Mather’s sympathy for the possessed, when Mather

stated, “the devil have sometimes represented the shapes of persons not

only innocent, but also the very virtuous.” And John Demos considered Mather a moderating influence on the trial.

After the trial, Cotton Mather was unrepentant for his role. Of the principal actors in the trial, whose lives are recorded after it, only Cotton Mather and William Stoughton never admitted any guilt. Indeed, in the years after the trial Mather became an increasingly vehement defender of the trial. At the request of then Lt. Gov. William Stoughton, Mather wrote Wonders of the Invisible World in 1693. The book contained a few of Mather’s sermons, the conditions of the colony and a description of witch trials in Europe. Mather also contradicted his own advice, which he himself had given in Return of the Several Ministers, by defending the use of spectral evidence. Wonders of the Invisible World appeared at the same time as Increase Mather’s Case of Conscience, a book critical of the trials. Upon reading Wonders of the Invisible World, Increase Mather publicly burned the book in Harvard Yard. Also, Boston merchant Robert Calef began what became an eight year campaign of attacks on Cotton Mather.

The last event in Cotton Mather's involvement with witchcraft was his attempt to cure Mercy Short and Margaret Rule. Mather later wrote A Brand Pluck’d Out of the Burning and Another Brand Pluckt Out of the Burning about curing the women.

Magnalia Christi Americana,

considered Mather's greatest work, was published in 1702, when he was

39. The book, which was done through several biographies of saints, describes

the process of the New England settlement. It was

composed of seven total books. Despite being one of Mather's best known works, many have openly criticized it,

labeling it as hard to follow and understand, and poorly paced and

organized. However, other critics have praised Mather's works, believing

it to be one of the best efforts at properly documenting the

establishment of America and growth of the people.

When Cotton Mather died, he had an abundance of unfinished writings left behind, including one entitled The Biblia Americana. Mather believed that Biblia Americana was the best thing he had ever written, believing it to be his masterwork.

Biblia Americana contained Cotton Mather's thoughts and opinions on the Bible and how he interpreted it. Biblia Americana is

incredibly large and Mather worked on it from 1693 – 1728, when he died.

Mather tried to convince others that philosophy and science could work

together with religion instead of against it. People did not have to

choose one or the other and in Biblia Americana Mather looked at the Bible through a scientific perspective, the complete opposite of when he wrote The Christian Philosopher, in which he decided to approach science in a religious manner.

In 1721 The Christian Philosopher was published. Written by Mather, it was the first systematic book on science published in America. Mather attempted to show how Newtonian science and religion were in harmony. It was in part based on Robert Boyle's The Christian Virtuoso (1690).

Mather also took inspiration from Hayy ibn Yaqdhan, a philosophical novel by Abu Bakr Ibn Tufail (who he refers to as "Abubekar"), a 12th century Islamic philosopher. Despite condemning the 'Mahometans' as infidels, he viewed the protagonist of the novel, Hayy, as a model for his ideal Christian philosopher and monotheistic scientist'. Mather also viewed Hayy as a noble savage and applied this in the context of attempting to understand the Native American Indians in order to convert them to Puritan Christianity.

The Puritan execution sermon, preached on the occasion of a public hanging, then quickly printed up in pamphlet form and sold for a few pence, was an early form of true crime literature. Mather's first published sermon, which appeared in 1686, concerned the crime and punishment of James Morgan, a reprobate who in a drunken rage impaled a man with an iron spit. Thirteen years later, following the execution of a Boston woman named Sarah Threeneedles for killing her baby, Mather issued Pillars of Salt. This compilation of a dozen accounts (half of which, including the case of Morgan, had been previously published) stands as a landmark work, a Puritan precursor of the true crime miscellanies that, stripped of all religious intent, would become a staple of the genre in subsequent centuries. In 2008 The Library of America reprinted the entirety of Pillars of Salt in its two century retrospective of American True Crime.

The Boston Ephemeris was an almanac written by Mather in 1686. The content was similar to what is known today as the Farmer’s Almanac. This was particularly important because it shows that Cotton Mather had influence in mathematics during the time of Puritan New England. This almanac contained a significant amount of astronomy, celestial motions of the sun, planets, and stars, as did many almanacs of the time. It also included “information such as weather forecasts, farmers' planting dates, astronomical information, and tide tables, Astronomical data and various statistics, such as the times of the rising and setting of the sun and moon, eclipses, hours of full tide, stated festivals of churches, terms of courts, lists of all types, timelines, and more.” Mather had within the text of the Almanac the positions and motions of these celestial bodies, which he must have calculated by hand.