<Back to Index>

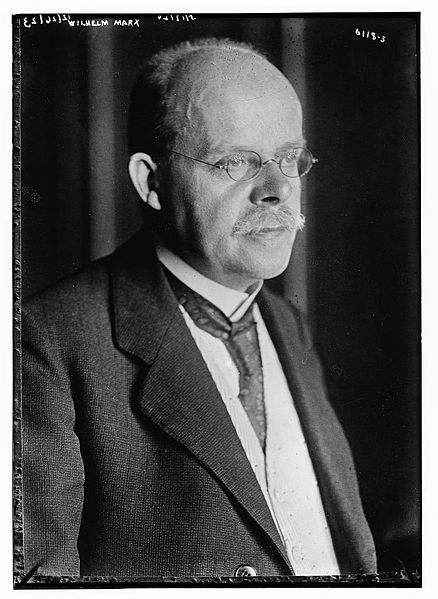

- Chancellor of Germany Gustav Stresemann, 1878

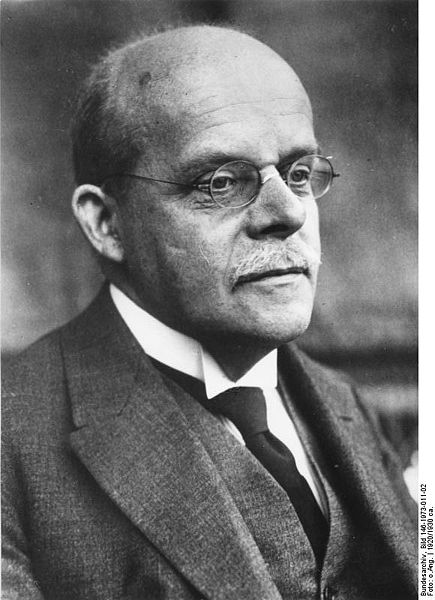

- Chancellor of Germany Wilhelm Marx, 1863

PAGE SPONSOR

Gustav Stresemann (May 10, 1878 – October 3, 1929) was a German politician and statesman who served as Chancellor and Foreign Minister during the Weimar Republic. He was co-laureate of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1926.

Stresemann's

politics defy easy categorization. Arguably, his most notable

achievement was reconciliation between Germany and France, for which he

and Aristide Briand received the Peace Prize.

Stresemann was born on May 10, 1878 in the Köpenicker Straße area of southeast Berlin, the youngest of seven children. His father worked as a beer bottler and distributor, and also ran a small bar out of the family home, as well as renting rooms for extra money. The family was lower middle class, but relatively well off for the neighborhood, and had sufficient funds to provide Gustav with a high quality education. Stresemann was an excellent student, particularly excelling in German literature and poetry. In an essay written when he left school, he noted that he would have enjoyed becoming a teacher, but he would only have been qualified to teach languages or the natural sciences, which were not his primary areas of interest. Thus, he entered the University of Berlin in 1897 to study political economy. Through this course of studies, Stresemann was exposed to the principal ideological arguments of his day, particularly the German debate about socialism.

During his university years, Stresemann also became active in Burschenschaften movement of student fraternities, and became editor, in April 1898, of the Allgemeine Deutsche Universitäts - Zeitung, a newspaper run by Konrad Kuster, a leader in the liberal portion of the Burschenschaften. His editorials for the paper were often political, and dismissed most of the contemporary political parties as broken in one way or another. In these early writings, he set out views that combined liberalism with strident nationalism, a combination that would dominate his views for the rest of his life. In 1898, Stresemann left the University of Berlin, transferring to the University of Leipzig so that he could pursue a doctorate. He completed his studies in January 1901, submitting a thesis on the bottled beer industry in Berlin, which received a relatively high grade.

In 1902 he founded the Saxon Manufacturers' Association. In 1903 he married Käte Kleefeld (1885 – 1970), daughter of a wealthy Jewish Berlin businessman. At that time he was also a member of Friedrich Naumann's National - Social Association. In 1906 he was elected to the Dresden town council. Though he had initially worked in trade associations, Stresemann soon became a leader of the National Liberal Party in Saxony. In 1907, he was elected to the Reichstag, where he soon became a close associate of party chairman Ernst Bassermann. However, his support of expanded social welfare programs did not sit well with some of the party's more conservative members, and he lost his post in the party's executive committee in 1912. Later that year he lost both his Reichstag and town council seats. He returned to business and founded the German - American Economic Association. In 1914 he returned to the Reichstag. He was exempted from war service due to poor health. With Bassermann kept away from the Reichstag by either illness or military service, Stresemann soon became the National Liberals' de facto leader. After Bassermann's death in 1917, Stresemann succeeded him as party leader.

The evolution of his political ideas appears somewhat erratic. Initially, in the German Empire, Stresemann was associated with the left wing of the National Liberals. During World War I, he gradually moved to the right, expressing his support of the monarchy and Germany's expansionist goals. He was a vocal proponent of unrestricted submarine warfare. However, he still favored an expansion of the social welfare program, and also supported an end to the restrictive Prussian franchise.

When the Allies' peace terms became known, Constantin Fehrenbach denounced them and claimed "the will to break the chains of slavery would be implanted" into a generation of Germans. Stresemann said of this speech: "He was inspired in that hour by God to say what was felt by the German people. His words, spoken under Fichte's portrait, the final words of which merged into “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles”, made it an unforgettably solemn hour. There was in that sense a kind of uplifting grandeur. The impression left on all was tremendous".

Stresemann briefly joined the German Democratic Party after the war, but was expelled for his association with the right wing. He then gathered most of the right wing of the old National Liberal Party into the German People's Party (German: Deutsche Volkspartei, DVP), with himself as chairman. Most of its support came from middle class and upper class Protestants. The DVP platform promoted Christian family values, secular education, lower tariffs, opposition to welfare spending and agrarian subsides and hostility to "Marxism" (that is, the Communists, and also the Social Democrats).

The DVP was initially seen, along with the German National People's Party,

as part of the "national opposition" to the Weimar Republic,

particularly for its grudging acceptance of democracy and its ambivalent

attitude towards the Freikorps and the Kapp Putsch in

1920. By late 1920, Stresemann gradually moved to cooperation with the

parties of the left and center — possibly in reaction to political

murders like that of Walther Rathenau. However, he remained a monarchist at heart.

On August 13, 1923, in the midst of the Ruhr Crisis, he was appointed Chancellor and Foreign Minister of a grand coalition government. As Chancellor, Stresemann went a long way towards resolving the crisis through the Dawes plan which involved a 800 million mark loan from USA. In the so-called year of crises (1923) he showed strength by calling off the popular passive resistance at the Ruhr. Since Germany was no longer able to pay the striking workers, more and more money was printed, which finally led to hyperinflation. Hans Luther, who was the current finance minister, ended this disastrous process by introducing a new currency, the Rentenmark, which reassured the people that the democratic system was willing and able to solve urgent problems.

Stresemann's decision to end passive resistance was motivated by his view that making a good faith effort to fulfill the terms of Versailles was the only way to win relief from the treaty's harsher provisions. He, like virtually every German, felt Versailles was an onerous Diktat that sullied the nation's honor. However, he felt that trying to fulfill the treaty's terms was the only way Germany could demonstrate that the reparations bill was truly beyond its capacity. He also wished to recover the Rhineland, as he wrote to the Crown Prince on 23 July 1923: "The most important objective of German politics is the liberation of German territory from foreign occupation. First, we must remove the strangler from our throat".

However, some of his moves - like his refusal to deal firmly with culprits of the Beer Hall Putsch - alienated the Social Democrats. They left the coalition and arguably caused its collapse on November 23, 1923.

Stresemann remained as Foreign Minister in the government of his successor, Centrist Wilhelm Marx. He remained foreign minister for the rest of his life in eight successive governments ranging from the center right to the center left.

As Foreign Minister, Stresemann had numerous achievements. His first notable achievement was the Dawes Plan of 1924, which reduced Germany's overall reparations commitment and reorganized the Reichsbank.

After Sir Austen Chamberlain became British Foreign Secretary, he wanted a British guarantee to France and Belgium as the Anglo - American guarantee had fallen due to the United States' refusal to ratify the Treaty of Versailles. Stresemann later wrote: "Chamberlain had never been our friend. His first act was to attempt to restore the old Entente through a three power alliance of England, France and Belgium, directed against Germany. German diplomacy faced a catastrophic situation". Stresemann conceived the idea that Germany would guarantee her western borders and pledged never to invade Belgium and France again, along with a guarantee from Britain that they would come to Germany's aid if attacked by France. Germany was in no position at the time to attack, as Stresemann wrote to the Crown Prince: "The renunciation of a military conflict with France has only a theoretical significance, in so far as there is no possibility of a war with France". Stresemann negotiated the Locarno Treaties with Britain, France, Italy, and Belgium. On the third day of negotiations Stresemann explained Germany's demands to the French Foreign Secretary, Aristide Briand. As Stresemann recorded, Briand "almost fell off his sofa, when he heard my explanations". Stresemann said that Germany alone should not make sacrifices for peace; European countries should cede colonies to Germany; the disarmament control commission should leave Germany; the Anglo - French occupation of the Rhineland should be ended; and Britain and France should disarm as Germany had done. The Treaties were signed in October 1925 at Locarno. Germany officially recognized the post World War I western border for the first time, and was guaranteed peace with France, and promised admission to the League of Nations and evacuation of the last Allied occupation troops from the Rhineland. Germany's eastern borders were guaranteed to Poland only by France, not by a general agreement.

Stresemann was not willing to conclude a similar treaty with Poland: "There will be no Locarno of the east" he said. Moreover he never excluded the use of force to regain the eastern territories of Germany which had come under Polish control as a consequence of the Treaty of Versailles.

After this reconciliation with the Versailles powers, Stresemann moved to allay the growing suspicion of the Soviet Union. He said to Nikolay Krestinsky in June 1925, as recorded in his diary: "I had said I would not come to conclude a treaty with Russia so long as our political situation in the other direction was not cleared up, as I wanted to answer the question whether we had a treaty with Russia in the negative". The Treaty of Berlin signed in April 1926 reaffirmed and strengthened the Rapallo Treaty of 1922. In September 1926, Germany was admitted to the League of Nations as permanent member of the Security Council. This was a sign that Germany was quickly becoming a "normal" state and assured the Soviet Union of Germany's sincerity in the Treaty of Berlin. Stresemann wrote to the Crown Prince: "All the questions which to-day preoccupy the German people can be transformed into as many vexations for the Entente by a skilful orator before the League of Nations". As Germany now had a veto on League resolutions, she could gain concessions from other countries on modifications on the Polish border or Anschluss with Austria, as other countries needed her vote. Germany could now act as "the spokesman of the whole German cultural community" and thereby provoke the German minorities in Czechoslovakia and Poland.

Stresemann was co-winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1926 for these achievements.

Germany signed the Kellogg - Briand Pact in August 1928. It renounced the use of violence to resolve international conflicts. Although Stresemann did not propose the pact, Germany's adherence convinced many people that Weimar Germany was a Germany that could be reasoned with. This new insight was instrumental in the Young Plan of February 1929 which led to more reductions in German reparations payment.

Gustav Stresemann's success owed much to his friendly personal character and his willingness to be pragmatic. He was close personal friends with many influential foreigners. The most noted was Briand, with whom he shared the Peace Prize.

Stresemann was not, however, in any sense pro - French. His main preoccupation was how to free Germany from the burden of reparations payments to Britain and France, imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. His

strategy for this was to forge an economic alliance with the United States.

The U.S. was Germany's main source of food and raw materials, and one

of Germany's largest export markets for manufactured goods. Germany's

economic recovery was thus in the interests of the U.S., and gave the

U.S. an incentive to help Germany escape from the reparations burden.

The Dawes and Young plans were the result of this strategy. Stresemann

had a close relationship with Herbert Hoover, who was Secretary of Commerce in 1921 - 28 and President from 1929. This strategy worked remarkably well until it was derailed by the Great Depression after Stresemann's death.

During his period in the foreign ministry, Stresemann came more and more to accept the Republic, which he had at first rejected. By the mid 1920s, having contributed much to a (temporary) consolidation of the feeble democratic order, Stresemann was regarded as a Vernunftrepublikaner (republican by reason) - someone who accepted the Republic as the least of all evils, but was in their heart still loyal to the monarchy. The conservative opposition criticized him for his supporting the republic and fulfilling too willingly the demands of the Western powers. Along with Matthias Erzberger and others, he was attacked as a Erfüllungspolitiker ("fulfillment politician").

In

1925, when he first proposed an agreement with France, he made it clear

that in doing so he intended to "gain a free hand to secure a peaceful

change of the borders in the East and [...] concentrate on a later

incorporation of German territories in the East". In the same year, while Poland was in a state of political and economic crisis, Stresemann began a trade war against

the country. Stresemann hoped for an escalation of the Polish crisis,

which would enable Germany to regain territories ceded to Poland after

World War I, and he wanted Germany to gain a larger market for its

products there. So Stresemann refused to engage in any international

cooperation that would have "prematurely" restabilized the Polish

economy. In response to a British proposal, Stresemann wrote to the

German ambassador in London: "[A] final and lasting recapitalization of

Poland must be delayed until the country is ripe for a settlement of the

border according to our wishes and until our own position is

sufficiently strong". According to Stresemann's letter, there should be

no settlement "until [Poland's] economic and financial distress has

reached an extreme stage and reduced the entire Polish body politic to a

state of powerlessness".

Gustav Stresemann died of a stroke in October 1929 at the age of 51. His massive gravesite is situated on the Luisenstadt Cemetery at Südstern in Berlin Kreuzberg, and includes work by the German sculptor Hugo Lederer. Stresemann's sudden and premature death, as well as the death of his "pragmatic moderate" French counterpart Aristide Briand in 1932, and the assassination of Briand's successor Louis Barthou in 1934, left a vacuum in European statesmanship that further tilted the slippery slope towards World War II.

Gustav and Käthe had two sons, Wolfgang and Joachim Stresemann.

Wilhelm Marx (January 15, 1863– August 5, 1946) was a German lawyer, Catholic politician and a member of the Center Party. He was Chancellor of the German Reich twice, from 1923 to 1925 and again from 1926 to 1928, and also served briefly as minister president of Prussia in 1925, during the Weimar Republic.

Born in Cologne to a teacher, Marx passed his Abitur at the Marzellengymnasium in 1881. He then studied jurisprudence at the University of Bonn. As student he became a member of K.St.V. Arminia. After his degree in law, he worked as an assessor in both Cologne and Waldbröl and later in the land registry in Simmern. From 1894 Marx worked as a judge in Elberfeld. Ten years later, he returned to Cologne and Düsseldorf, where he had the highest rank possible in Prussia for a Catholic who was also active in the Center Party.

Marx married Johanna Verkoyen in 1891 and they had four children.

He served as Chancellor of Germany from 1923 to 1925 and again from 1926 to 1928, and was the Center Party's (and, in the second round, the entire Weimar Coalition's) candidate in the1925 presidential election. But in the runoff he was defeated by Paul von Hindenburg, as Ernst Thälmann the Communist candidate also stood and split the vote.

Marx took an active part in the Catholic Center Party. In 1899, he presided the Zentrums - Vereinin Elberfeld; in 1908 he became chairman of the Center Party in Düsseldorf.

From 1899 to 1918 Marx was a member of the Landtag of Prussia. From 1910 he was a member of the Reichstag, where he became a member of the executive committee of the Center Party faction. There, he specialized in the field of school and culture politics.

During World War I he expressed his opinion against annexation and for a peace resolution. Thus, he was elected into the Nationalversammlung of Weimar. He supported the Treaty of Versailles during the occupation of the Rhineland in 1923 because he thought that if Germany did not accept it, the Rhineland would be separated from Prussia. Marx also tried to unify the Center Party and to support the government, using his style of politics and an appeal to Catholicism.

When the cabinet of Gustav Stresemann failed in 1923, Marx became chancellor, leading the tenth German cabinet since 1919. His first term lasted 13 months, his second term lasted 25 months. In this time, he presided over four cabinets, the first two being civic minority governments, later joined by the DNVP. His foreign minister was Gustav Stresemann, whose politics led to a toleration by the SPD. During Marx's terms, he managed to stabilize the German economy after the hyperinflation of 1923 by introducing a new currency. By the end of 1924, the state of emergency could be repealed. The cabinets led by Marx also accepted the Dawes Plan. In his second term, Germany joined the League of Nations, and Marx managed to unseat General Hans von Seeckt, who wanted to make the army a "state within the state". On the other hand, during his terms the Reichswehr secretly cooperated with the Soviet Russian army to circumvent the Treaty of Versailles.

In 1925 Marx also became minister president of Prussia, and in 1926 he was minister of justice in the cabinet of his successor, Hans Luther. He was a member of the Reichstag up to 1932. During the Nazi period, and after World War II, he lived in Bonn, where he died.