<Back to Index>

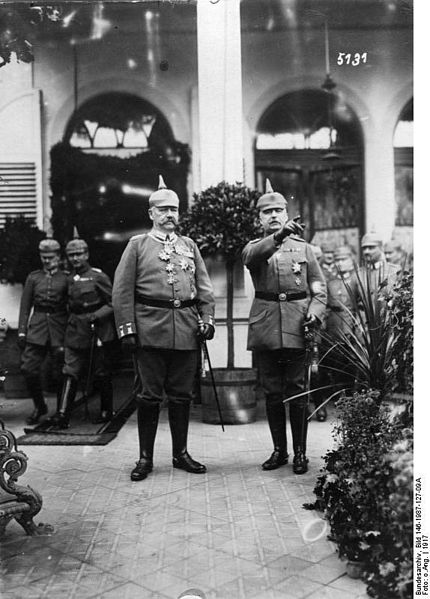

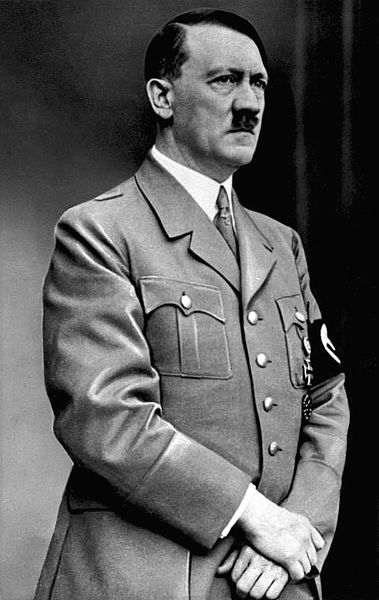

- Chancellor of Germany Adolf Hitler, 1889

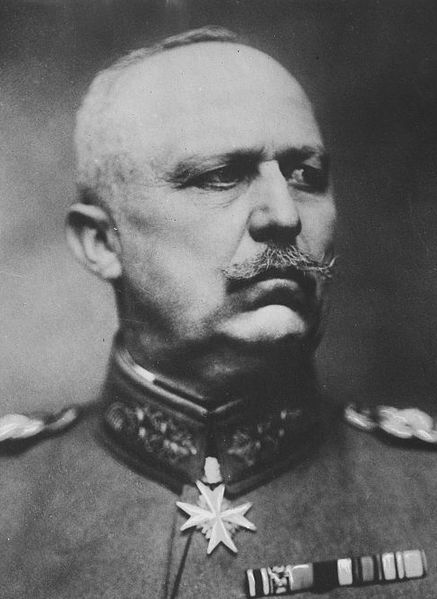

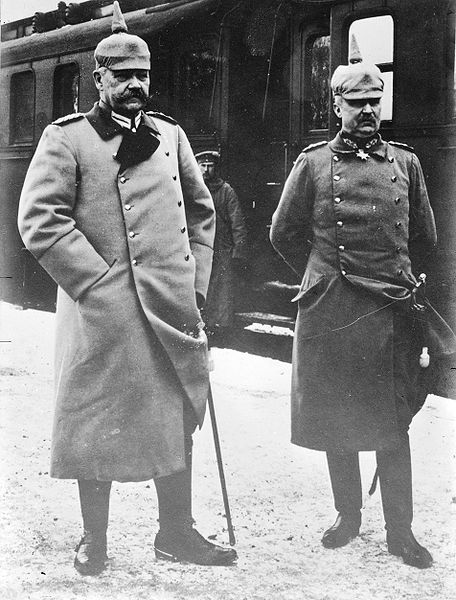

- General of the German Imperial Army Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff, 1865

PAGE SPONSOR

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party (German: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP), commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state (as Führer und Reichskanzler) from 1934 to 1945. Hitler is most commonly associated with the rise of fascism in Europe, World War II, and the Holocaust.

A decorated veteran of World War I, Hitler joined the German Workers' Party, precursor of the Nazi Party, in 1919, and became leader of the NSDAP in 1921. In 1923 Hitler attempted a coup d'état, known as the Beer Hall Putsch, at the Bürgerbräukeller beer hall in Munich. The failed coup resulted in Hitler's imprisonment, during which time he wrote his memoir, Mein Kampf (My Struggle). After his release in 1924, Hitler gained support by promoting Pan - Germanism, antisemitism, and anti - communism with charismatic oratory and propaganda. He was appointed chancellor in 1933 and transformed the Weimar Republic into the Third Reich, a single party dictatorship based on the totalitarian and autocratic ideology of Nazism.

Hitler's avowed aim was to establish a New Order of absolute Nazi German hegemony in continental Europe. His foreign and domestic policies had the goal of seizing Lebensraum (living space) for the Germanic people. He oversaw the rearmament of Germany and the invasion of Poland by the Wehrmacht in September 1939, which led to the outbreak of World War II in Europe.

Under Hitler's direction, in 1941 German forces and their European allies occupied most of Europe and North Africa. These gains were gradually reversed after 1941, and in 1945 the Allied armies defeated the German army. Hitler's racially motivated policies resulted in the deaths of as many as 17 million people, including an estimated six million Jews and between 500,000 and 1,500,000 Roma targeted in the Holocaust.

In the final days of the war, during the Battle of Berlin in 1945, Hitler married his long time mistress, Eva Braun. On 30 April 1945 — less than two days later — the two committed suicide to avoid capture by the Red Army, and their corpses were burned.

Hitler's father, Alois Hitler (1837 – 1903), was the illegitimate child of Maria Anna Schicklgruber. Alois's birth certificate did not list the name of the father, and the child bore his mother's surname. In 1842 Johann Georg Hiedler married Maria, and in 1876 Johann testified before a notary and three witnesses that he was the father of Alois. Nazi official Hans Frank suggested the existence of letters claiming that Alois' mother was employed as a housekeeper for a Jewish family in Graz and that the family's 19 year old son, Leopold Frankenberger, had fathered Alois. However, no Frankenberger, Jewish or otherwise, is registered in Graz for that period. Historians now doubt the claim that Alois' father was Jewish; all Jews had been expelled from Graz under Maximilian I in the 15th century, and were not allowed to settle in Styria until the Basic Laws were passed in 1849.

At age 39 Alois assumed the surname Hitler, also spelled as Hiedler, Hüttler, or Huettler;

the name was probably regularized to its final spelling by a clerk. The

origin of the name is either "one who lives in a hut" (Standard German Hütte), "shepherd" (Standard German hüten "to guard", English heed), or is from the Slavic words Hidlar and Hidlarcek.

Adolf Hitler was born on 20 April 1889 at around 6:30 pm at the Gasthof zum Pommer, an inn in Ranshofen, a village annexed in 1938 to the municipality of Braunau am Inn, Upper Austria. He was the third of five children to Alois Hitler and Klara Pölzl (1860 – 1907). Adolf's older siblings – Gustav and Ida – died in infancy. When Hitler was three, the family moved to Passau, Germany. There he would acquire the distinctive lower Bavarian dialect, rather than Austrian German, which marked his speech all of his life. In 1894, the family relocated to Leonding near Linz, and in June 1895, Alois retired to a small landholding at Hafeld near Lambach, where he tried his hand at farming and beekeeping. Adolf attended school in nearby Fischlham, and in his free time, he played "Cowboys and Indians". Hitler became fixated on warfare after finding a picture book about the Franco - Prussian War among his father's belongings.

The move to Hafeld appears to have coincided with the onset of intense father - son conflicts, caused by Adolf's refusal to conform to the strict discipline of his school. Alois Hitler's farming efforts at Hafeld ended in failure, and in 1897 the family moved to Lambach. Hitler attended a Catholic school in an 11th century Benedictine cloister, the walls of which bore engravings and crests that contained the symbol of the swastika. In Lambach the eight year old Hitler took singing lessons, sang in the church choir, and even entertained thoughts of becoming a priest. In 1898 the family returned permanently to Leonding. The death of his younger brother Edmund from measles on 2 February 1900 deeply affected Hitler. He changed from being confident and outgoing and an excellent student, to a morose, detached, and sullen boy who constantly fought with his father and his teachers.

Alois had made a successful career in the customs bureau and wanted his son to follow in his footsteps. Hitler later dramatized an episode from this period when his father took him to visit a customs office, depicting it as an event that gave rise to an unforgiving antagonism between father and son who were both equally strong - willed. Ignoring his son's desire to attend a classical high school and become an artist, in September 1900 Alois sent Adolf to the Realschule in Linz, a technical high school of about 300 students. (This was the same high school that Adolf Eichmann would attend some 17 years later.) Hitler rebelled against this decision, and in Mein Kampf revealed that he did poorly in school, hoping that once his father saw "what little progress I was making at the technical school he would let me devote myself to my dream."

Hitler became obsessed with German nationalism from a young age as a way of rebelling against his father, who was proudly serving the Austrian government. Although many Austrians considered themselves Germans, they were loyal to Austria. Hitler expressed loyalty only to Germany, despising the declining Habsburg Monarchy and its rule over an ethnically variegated empire. Hitler and his friends used the German greeting "Heil", and sang the German anthem "Deutschland Über Alles" instead of the Austrian Imperial anthem.

After

Alois' sudden death on 3 January 1903, Hitler's behavior at the

technical school became even more disruptive, and he was asked to leave

in 1904. He enrolled at the Realschule in Steyr in

September 1904, but upon completing his second year, he and his friends

went out for a night of celebration and drinking. While drunk, Hitler

tore up his school certificate and used the pieces as toilet paper. The

stained certificate was brought to the attention of the school's

principal, who "... gave him such a dressing - down that the boy was

reduced to shivering jelly. It was probably the most painful and

humiliating experience of his life." Hitler was expelled, never to return to school again.

From 1905, Hitler lived a bohemian life in Vienna financed by orphan's benefits and support from his mother. The Academy of Fine Arts Vienna rejected him twice, in 1907 and 1908, because of his "unfitness for painting", and the director recommended that he study architecture. However, he lacked the academic credentials required for architecture school. He would later write:

In a few days I myself knew that I should some day become an architect. To be sure, it was an incredibly hard road; for the studies I had neglected out of spite at the Realschule were sorely needed. One could not attend the Academy's architectural school without having attended the building school at the Technik, and the latter required a high school degree. I had none of all this. The fulfillment of my artistic dream seemed physically impossible.

On 21 December 1907, Hitler's mother died at age 47. He worked as a casual laborer and eventually as a painter, selling watercolors. After being rejected a second time by the Academy of Arts, Hitler ran out of money. In 1909, he lived in a shelter for the homeless, and by 1910, he had settled into a house for poor working men on Meldemannstraße.

Hitler stated that he first became an anti - semite in Vienna, which had a large Jewish community, including Orthodox Jews who had fled the pogroms in Russia.

There were few Jews in Linz. In the course of centuries their outward appearance had become Europeanized and had taken on a human look; in fact, I even took them for Germans. The absurdity of this idea did not dawn on me because I saw no distinguishing feature but the strange religion. The fact that they had, as I believed, been persecuted on this account sometimes almost turned my distaste at unfavorable remarks about them into horror. Thus far I did not so much as suspect the existence of an organized opposition to the Jews. Then I came to Vienna.

Once, as I was strolling through the Inner City, I suddenly encountered an apparition in a black caftan and black hair locks. Is this a Jew? was my first thought. For, to be sure, they had not looked like that in Linz. I observed the man furtively and cautiously, but the longer I stared at this foreign face, scrutinizing feature for feature, the more my first question assumed a new form: Is this a German?

Hitler's account has been questioned by his childhood friend, August Kubizek, who suggested that Hitler was already a "confirmed anti - semite" before he left Linz for Vienna. Brigitte Hamann has challenged Kubizek's account, writing that "of all those early witnesses who can be taken seriously Kubizek is the only one to portray young Hitler as an anti - Semite and precisely in this respect he is not trustworthy." If Hitler was an anti - semite even before settling in Vienna, apparently he did not act on his views. He was a frequent dinner guest in a wealthy Jewish home; he interacted well with Jewish merchants, and sold his paintings almost exclusively to Jewish dealers.

At the time Hitler lived there, Vienna was a hotbed of traditional religious prejudice and 19th century racism. Fears of being overrun by immigrants from the East were widespread, and the populist mayor, Karl Lueger, was adept at exploiting the rhetoric of virulent antisemitism for political effect. Georg Schönerer's pangermanic ethnic antisemitism had a strong following and base in the Mariahilf district, where Hitler lived. Local newspapers such as the Deutsches Volksblatt, which Hitler read, fanned prejudices, as did Rudolf Vrba's writings, which played on Christian fears of being swamped by an influx of eastern Jews. He probably read occult writings, such as the antisemitic magazine Ostara, published by Lanz von Liebenfels. Hostile to what he saw as Catholic "Germanophobia", he developed a strong admiration for Martin Luther. Luther's foundational antisemitic writings were to play an important role in later Nazi propaganda.

Hitler received the final part of his father's estate in May 1913 and moved to Munich. He wrote in Mein Kampf that he had always longed to live in a "real" German city. In Munich, he further pursued his interest in architecture and studied the writings of Houston Stewart Chamberlain, who, a decade later, was to become the first person of national — and even international — repute to align himself with Hitler and the Nazi movement. Hitler also may have left Vienna to avoid conscription into the Austrian army; he was disinclined to serve the Habsburg state and was repulsed by what he perceived as a mixture of "races" in the Austrian army. After a physical exam on 5 February 1914, he was deemed unfit for service and returned to Munich. When Germany entered World War I in August 1914, he successfully petitioned King Ludwig III of Bavaria for permission to serve in a Bavarian regiment.

Hitler served as a runner on the Western Front in France and Belgium in the Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 16. He experienced major combat, including the First Battle of Ypres, the Battle of the Somme, the Battle of Arras, and the Battle of Passchendaele.

He was decorated for bravery, receiving the Iron Cross, Second Class, in 1914. Recommended by Hugo Gutmann, he received the Iron Cross, First Class, on 4 August 1918, a decoration rarely awarded to one of Hitler's rank (Gefreiter).

Hitler's post at regimental headquarters, where he had frequent

interactions with senior officers, may have helped him receive this

decoration. The regimental staff, however, thought Hitler lacked leadership skills, and he was never promoted. He also received the Wound Badge on 18 May 1918.

While serving at regimental headquarters Hitler pursued his artwork, drawing cartoons and instructions for an army newspaper. In October 1916 he was wounded either in the groin area or the left thigh when a shell exploded in the dispatch runners' dugout during the Battle of the Somme. Hitler spent almost two months in the Red Cross hospital at Beelitz. He returned to his regiment on 5 March 1917. On 15 October 1918, Hitler was temporarily blinded by a mustard gas attack. It has been suggested that his blindness may have been an hysterical symptom brought on by the shock at the rapid reversal of Germany's war fortunes. He was hospitalized in Pasewalk.

Hitler became embittered over the collapse of the war effort. It was during this time that his ideological development began to firmly take shape. He described the war as "the greatest of all experiences", and was praised by his commanding officers for his bravery. The experience made Hitler a passionate German patriot, and he was shocked by Germany's capitulation in November 1918. Like many other German nationalists, he believed in the Dolchstoßlegende (Stab - in - the - back legend), which claimed that the German army, "undefeated in the field," had been "stabbed in the back" on the home front by civilian leaders and Marxists, later dubbed the November Criminals.

The Treaty of Versailles stipulated that Germany must relinquish several of its territories and demilitarize the Rhineland. The treaty imposed economic sanctions and levied reparations on the country. Many Germans perceived the treaty — especially Article 231, which declared Germany responsible for the war — as a humiliation. The economic, social, and political conditions in Germany effected by the war and the Versailles treaty were later exploited by Hitler for political gains.

After World War I, Hitler remained in the army and returned to Munich. In July 1919 he was appointed Verbindungsmann (intelligence agent) of an Aufklärungskommando (reconnaissance commando) of the Reichswehr, both to influence other soldiers and to infiltrate the German Workers' Party (DAP). While he studied the activities of the DAP, Hitler became impressed with founder Anton Drexler's antisemitic, nationalist, anti - capitalist, and anti - Marxist ideas. Drexler favored a strong active government, a "non - Jewish" version of socialism,

and solidarity among all members of society. Impressed with Hitler's

oratory skills, Drexler invited him to join the DAP. Hitler accepted on

12 September 1919, becoming the party's 55th member.

At the DAP, Hitler met Dietrich Eckart, one of its early founders and a member of the occult Thule Society. Eckart became Hitler's mentor, exchanging ideas with him and introducing him to a wide range of people in Munich society. Hitler thanked Eckart and paid tribute to him in the second volume of Mein Kampf. To increase the party's appeal, the party changed its name to the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Workers Party – NSDAP). Hitler designed the party's banner of a swastika in a white circle on a red background.

After his discharge from the army in March 1920, Hitler began working full time for the party. In February 1921 — already highly effective at speaking to large audiences — he spoke to a crowd of over six thousand in Munich. To publicize the meeting, two truckloads of party supporters drove around town waving swastika flags and throwing leaflets. Hitler soon gained notoriety for his rowdy, polemic speeches against the Treaty of Versailles, rival politicians, and especially against Marxists and Jews. At the time, the NSDAP was centered in Munich, a major hotbed of anti - government German nationalists determined to crush Marxism and undermine the Weimar Republic.

In June 1921, while Hitler and Eckart were on a fundraising trip to Berlin, a mutiny broke out within the DAP in Munich. Members of the DAP's executive committee, some of whom considered Hitler to be too overbearing, wanted to merge with the rival German Socialist Party (DSP). Hitler returned to Munich on 11 July 1921 and angrily tendered his resignation from the DAP. The committee members realized that his resignation would mean the end of the party. Hitler announced he would rejoin on the condition that he would replace Drexler as party chairman, and that the party headquarters would remain in Munich. The committee agreed; he rejoined the party as member 3,680. He still faced some opposition within the DAP: Hermann Esser and his allies printed 3,000 copies of a pamphlet attacking Hitler as a traitor to the party. In the following days, Hitler spoke to several packed houses and defended himself to thunderous applause. His strategy proved successful: at a general DAP membership meeting, he was granted absolute powers as party chairman, with only one nay vote cast.

Hitler's vitriolic beer hall speeches began attracting regular audiences. Early followers included Rudolf Hess, the former air force pilot Hermann Göring, and the army captain Ernst Röhm. The latter became head of the Nazis' paramilitary organization, the Sturmabteilung (SA,

"Storm Division"), which protected meetings and frequently attacked

political opponents. A critical influence on his thinking during this

period was the Aufbau Vereinigung, a conspiratorial group formed of White Russian exiles and early National Socialists. The group, financed with funds channeled from wealthy industrialists like Henry Ford, introduced him to the idea of a Jewish conspiracy, linking international finance with Bolshevism.

Hitler enlisted the help of World War I General Erich Ludendorff for an attempted coup known as the "Beer Hall Putsch" (also known as the "Hitler Putsch" or "Munich Putsch"). The Nazi Party had used Italian Fascism as a model for their appearance and policies, and in 1923, Hitler wanted to emulate Benito Mussolini's "March on Rome" by staging his own "Campaign in Berlin". Hitler and Ludendorff sought the support of Staatskommissar (state commissioner) Gustav von Kahr, Bavaria's de facto ruler. However, Kahr, along with Police Chief Hans Ritter von Seisser (Seißer) and Reichswehr General Otto von Lossow, wanted to install a nationalist dictatorship without Hitler.

Hitler wanted to seize a critical moment for successful popular agitation and support. On 8 November 1923, he and the SA stormed a public meeting of 3,000 people that had been organized by Kahr in the Bürgerbräukeller, a large beer hall in Munich. Hitler interrupted Kahr's speech and announced that the national revolution had begun, declaring the formation of a new government with Ludendorff. With his handgun drawn, Hitler demanded and got the support of Kahr, Seisser, and Lossow. Hitler's forces initially succeeded in occupying the local Reichswehr and police headquarters; however, neither the army nor the state police joined forces with him. Kahr and his consorts quickly withdrew their support and fled to join Hitler's opposition. The next day, Hitler and his followers marched from the beer hall to the Bavarian War Ministry to overthrow the Bavarian government on their "March on Berlin", but the police dispersed them. Sixteen NSDAP members and four police officers were killed in the failed coup.

Hitler fled to the home of Ernst Hanfstaengl, and by some accounts he contemplated suicide. He was depressed but calm when he was arrested on 11 November 1923 for high treason. His trial began in February 1924 before the special People's Court in Munich, and Alfred Rosenberg became temporary leader of the NSDAP. On 1 April Hitler was sentenced to five years' imprisonment at Landsberg Prison. He received friendly treatment from the guards and a lot of mail from supporters. The Bavarian Supreme Court issued a pardon and he was released from jail on 20 December 1924, against the state prosecutor's objections. Including time on remand, Hitler had served just over one year in prison.

While at Landsberg, Hitler dictated most of the first volume of Mein Kampf (My Struggle; originally entitled Four and a Half Years of Struggle against Lies, Stupidity, and Cowardice) to his deputy, Rudolf Hess. The book, dedicated to Thule Society member Dietrich Eckart, was an autobiography and an exposition of his ideology. Mein Kampf was influenced by The Passing of the Great Race by Madison Grant, which Hitler called "my Bible". Published

in two volumes in 1925 and 1926, it sold 228,000 copies between 1925

and 1932. One million copies were sold in 1933, Hitler's first year in

office.

At the time of Hitler's release from prison, politics in Germany had become less combative, and the economy had improved. This limited Hitler's opportunities for political agitation. As a result of the failed Beer Hall Putsch, the NSDAP and its affiliated organizations were banned in Bavaria. In a meeting with Prime Minister of Bavaria Heinrich Held on 4 January 1925, Hitler agreed to respect the authority of the state: he would only seek political power through the democratic process. The meeting paved the way for the ban on the NSDAP to be lifted. However, Hitler was barred from public speaking, a ban that remained in place until 1927. To advance his political ambitions in spite of the ban, Hitler appointed Gregor Strasser, Otto Strasser, and Joseph Goebbels to organize and grow the NSDAP in northern Germany. A superb organizer, Gregor Strasser steered a more independent political course, emphasizing the socialist element of the party's program.

Hitler ruled the NSDAP autocratically by asserting the Führerprinzip ("Leader principle"). Rank in the party was not determined by elections — positions were filled through appointment by those of higher rank, who demanded unquestioning obedience to the will of the leader.

The

stock market in the United States crashed on 24 October 1929. The

impact in Germany was dire: millions were thrown out of work and several

major banks collapsed. Hitler and the NSDAP prepared to take advantage

of the emergency to gain support for their party. They promised to

repudiate the Versailles treaty, strengthen the economy, and provide

jobs.

The Great Depression in Germany in 1930 provided a political opportunity for Hitler. Germans were ambivalent to the parliamentary republic, which faced strong challenges from right and left wing extremists. The moderate political parties were increasingly unable to stem the tide of extremism, and the German referendum of 1929 had helped to elevate Nazi ideology. The elections of September 1930 resulted in the break up of a grand coalition and its replacement by a minority cabinet. Its leader, chancellor Heinrich Brüning of the Center Party, governed through emergency decrees from the president, Paul von Hindenburg. Governance by decree would become the new norm and paved the way for authoritarian forms of government. The NSDAP rose from obscurity to win 18.3% of the vote and 107 parliamentary seats in the 1930 election, becoming the second largest party in parliament.

Hitler made a prominent appearance at the trial of two Reichswehr officers, Lieutenants Richard Scheringer and Hans Ludin, in the autumn of 1930. Both were charged with membership of the NSDAP, at that time illegal for Reichswehr personnel. The prosecution argued that the NSDAP was an extremist party, prompting defense lawyer Hans Frank to call on Hitler to testify in court. While testifying on 25 September 1930, Hitler stated that his party would pursue political power solely through democratic elections. Hitler's testimony won him many supporters in the officer corps.

Brüning's austerity measures brought little economic improvement and were extremely unpopular. Hitler exploited this weakness by targeting his political messages specifically to the segments of the population that had been affected by the inflation of the 1920s and the Depression, such as farmers, war veterans, and the middle class.

Hitler formally renounced his Austrian citizenship on 7 April 1925, but at the time did not acquire German citizenship. For almost seven years Hitler was stateless, unable to run for public office and faced the risk of deportation. On 25 February 1932 the interior minister of Brunswick, who was a member of the NSDAP, appointed Hitler as administrator for the state's delegation to the Reichsrat in Berlin, making Hitler a citizen of Brunswick, and thus of Germany.

In 1932 Hitler ran against von Hindenburg in the presidential elections. The viability of his candidacy was underscored by a 27 January 1932 speech to the Industry Club in Düsseldorf, which won him support from many of Germany's most powerful industrialists. However, Hindenburg had support from various nationalist, monarchist, Catholic, and republican parties and some social democrats. Hitler used the campaign slogan "Hitler über Deutschland" ("Hitler over Germany"), a reference to both his political ambitions and to his campaigning by aircraft. Hitler came in second in both rounds of the election, garnering more than 35% of the vote in the final election. Although he lost to Hindenburg, this election established Hitler as a strong force in German politics.

The absence of an effective government prompted two influential politicians, Franz von Papen and Alfred Hugenberg,

along with several other industrialists and businessmen, to write a

letter to von Hindenburg. The signers urged Hindenburg to appoint Hitler

as leader of a government "independent from parliamentary parties",

which could turn into a movement that would "enrapture millions of

people".

Hindenburg eventually and reluctantly agreed to appoint Hitler as chancellor after

two further parliamentary elections — in July and November 1932 — had not

resulted in the formation of a majority government. Hitler was to head a

short lived coalition government formed by the NSDAP and Hugenberg's

party, the German National People's Party (DNVP).

On 30 January 1933 the new cabinet was sworn in during a brief and

simple ceremony in Hindenburg's office. The NSDAP held three of the

eleven posts: Hitler was named chancellor, Hermann Göring was named minister without portfolio, and Wilhelm Frick was appointed minister of the interior.

As chancellor, Hitler worked against attempts by the NSDAP's opponents to build a majority government. Because of the political stalemate, Hitler asked President Hindenburg to dissolve the Reichstag again, and elections were scheduled for early March. On 27 February 1933, the Reichstag building was set on fire. Göring blamed a communist plot, because Dutch communist Marinus van der Lubbe was found in incriminating circumstances inside the burning building. At Hitler's urging, Hindenburg responded with the Reichstag Fire Decree of 28 February, which suspended basic rights, including habeas corpus. Activities of the German Communist Party were suppressed, and some 4,000 communist party members were arrested. Researchers, including Shirer and Bullock, are of the opinion that the NSDAP itself was responsible for starting the fire.

In

addition to political campaigning, the NSDAP engaged in paramilitary

violence and the spread of anti - communist propaganda in the days

preceding the election. On election day, 6 March 1933, the NSDAP's share

of the vote increased to 43.9%, and the party acquired the largest

number of seats in parliament. However, Hitler's party failed to secure

an absolute majority, necessitating another coalition with the DNVP.

On 21 March 1933 the new Reichstag was constituted with an opening ceremony held at the Garrison Church in Potsdam. This "Day of Potsdam" was staged to demonstrate reconciliation and unity between the revolutionary Nazi movement and old Prussia with its elites and perceived military virtues. Hitler appeared in a morning coat and humbly greeted the aged President Hindenburg.

In the Nazis' quest for full political control — they had failed to gain an absolute majority in the prior parliamentary election — Hitler's government brought the Ermächtigungsgesetz (Enabling Act) to a vote in the newly elected Reichstag. The legislation gave Hitler's cabinet full legislative powers for a period of four years, and allowed deviations from the constitution. Since the bill required a two - thirds majority to pass, the government needed the support of other parties. The position of the Center Party, the third largest party in the Reichstag, turned out to be decisive: under the leadership of Ludwig Kaas, the party decided to vote for the Enabling Act. It did so in return for Hitler's oral guarantees that President Hindenburg would retain his power of veto.

On

23 March, the Reichstag assembled in a replacement building under

turbulent circumstances. Ranks of SA men served as guards inside the

building, while large groups outside shouted slogans and threats toward

the arriving members of parliament. At

the end of the day, all parties except the Social Democrats voted in

favor of the bill — the Communists, as well as several Social Democrats,

were barred from attending the vote. The Enabling Act, along with the

Reichstag Fire Decree, transformed Hitler's government into a de facto dictatorship.

At the risk of appearing to talk nonsense I tell you that the National Socialist movement will go on for 1,000 years! ... Don't forget how people laughed at me 15 years ago when I declared that one day I would govern Germany. They laugh now, just as foolishly, when I declare that I shall remain in power!

— Adolf Hitler to a British correspondent in Berlin, June 1934

Having achieved full control over the legislative and executive branches of government, Hitler and his political allies embarked on systematic suppression of the remaining political opposition. After the dissolution of the Communist Party, the Social Democratic Party was also banned and all its assets seized. Many trade union delegates were flown to Berlin for May Day activities, and while they were there, Sturmabteilung (SA) stormtroopers demolished trade union offices around the country. On 2

May 1933 all trade unions were forced to dissolve, and their leaders

were arrested, with some sent to concentration camps. A

new union organization was formed, representing all workers,

administrators, and company owners together as one group. This new trade

union reflected the concept of national socialism in the spirit of

Hitler's "Volksgemeinschaft" (community of all German people).

On 14 July 1933 Hitler's Nazi Party was declared the only legal party in Germany. Hitler used the SA to pressure Hugenberg into resigning. The demands of the SA for more political and military power caused much anxiety among military, industrial, and political leaders. Hitler was prompted to purge the entire SA leadership, including Ernst Röhm, and other political adversaries (such as Gregor Strasser and former chancellor Kurt von Schleicher). These actions took place from 30 June to 2 July 1934, in what became known as the Night of the Long Knives. While some Germans were shocked by the killing, many others saw Hitler as the one who restored order to the country.

On 2 August 1934 President von Hindenburg died. In contravention to the Weimar Constitution, which called for presidential elections, Hitler's cabinet had enacted a law the previous day combining the offices of chancellor and president. The office of president was eliminated, and Hitler became head of state, styled as Führer und Reichskanzler (leader and chancellor). On 19 August, the merger of the presidency with the chancellorship was approved by a plebiscite with support of 84.6% of the electorate.

As head of state, Hitler now became Supreme Commander of the armed forces. The traditional loyalty oath of soldiers and sailors was altered to affirm loyalty directly to Hitler rather than to the office of commander - in - chief.

In early 1938, Hitler brought the armed forces under his direct control by forcing the resignation of his War Minister (formerly Defense Minister), Werner von Blomberg, on evidence that Blomberg's new wife had a police record for prostitution. Hitler also removed army commander Colonel - General Werner von Fritsch after the SS provided false allegations he had taken part in a homosexual relationship, which had led to blackmail. The episode became known as the Blomberg – Fritsch Affair. Hitler replaced the Ministry of War with the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (High Command of the Armed Forces, or OKW), headed by General Wilhelm Keitel. By early February 1938, twelve generals (apart from Blomberg and Fritsch) were also removed.

Having consolidated his political powers, Hitler suppressed or eliminated his opposition by a process termed Gleichschaltung ("bringing

into line"). He attempted to gain additional public support by vowing

to reverse the effects of the Depression and the Versailles treaty.

In 1935 Hitler appointed Hjalmar Schacht as Plenipotentiary for War Economy, in charge of preparing the economy for war. Reconstruction and rearmament were financed with currency manipulations, including credits through Mefo bills, printing money, and seizing the assets of people arrested as enemies of the State, including Jews. The unemployment rate fell substantially, from six million in 1932 to one million in 1936.

Nazi policies strongly encouraged women to bear children and stay at home. In a September 1934 speech to the NS - Frauenschaft (National Socialist Women's League), Hitler argued that for the German woman, her "world is her husband, her family, her children, and her home." The Cross of Honor of the German Mother was bestowed on women bearing four or more children.

Hitler oversaw one of the largest infrastructure improvement campaigns in German history, leading to the construction of dams, autobahns, railroads, and other civil works. Wages were slightly reduced in the pre – World War II years over those of the Weimar Republic, while the cost of living increased by 25%. From 1933 to 1934 wages suffered a 5% cut.

Hitler's government sponsored architecture on an immense scale. Albert Speer, instrumental in implementing Hitler's classicist reinterpretation of German culture, became the first architect of the Reich. In 1936 Hitler opened the summer Olympic games in Berlin. Hitler made some contributions to the design of the Volkswagen Beetle and charged Ferdinand Porsche with its design and construction.

On 20 April 1939 a lavish celebration was held for Hitler's 50th birthday, featuring military parades, visits from foreign dignitaries, Nazi banners, and thousands of flaming torches.

Historians such as David Schoenbaum and Henry Ashby Turner argue that Hitler's social and economic policies were modernization that had anti - modern goals. Others, including Rainer Zitelmann, have contended that Hitler had the deliberate strategy of pursuing a revolutionary modernization of German society.

In a meeting with German military leaders on 3 February 1933, Hitler spoke of "conquest for Lebensraum in the East and its ruthless Germanization" as his ultimate foreign policy objectives. In March 1933 State Secretary at the Auswärtiges Amt (Foreign Office) Prince Bernhard Wilhelm von Bülow issued a major statement of German foreign policy aims. The statement advocated Anschluss with Austria, the restoration of Germany's national borders of 1914, rejection of Part V of the Treaty of Versailles, the return of the former German colonies in Africa, and a German zone of influence in Eastern Europe. Hitler found Bülow's goals to be too modest.

In

his "peace speeches" of the mid 1930s, Hitler stressed the peaceful

goals of his policies and willingness to work within international

agreements. At the first meeting of his Cabinet in 1933, Hitler prioritized military spending over unemployment relief. In October 1933 Hitler withdrew Germany from the League of Nations and the World Disarmament Conference, and his Foreign Minister Baron Konstantin von Neurath stated that the French demand for sécurité was a principal stumbling block.

In March 1935 Hitler rejected Part V of the Versailles treaty by announcing an expansion of the German army to 600,000 members (six times the number stipulated in the Treaty of Versailles), including development of an Air Force (Luftwaffe) and increasing the size of the Navy (Kriegsmarine). Britain, France, Italy, and the League of Nations condemned these plans.

On 18 June 1935 the Anglo - German Naval Agreement (AGNA) was signed, allowing German tonnage to increase to 35% of that of the British navy. Hitler called the signing of the AGNA "the happiest day of his life" as he believed the agreement marked the beginning of the Anglo - German alliance he had predicted in Mein Kampf. France and Italy were not consulted before the signing, directly undermining the League of Nations and putting the Treaty of Versailles on the path towards irrelevance.

On

13 September 1935 Hitler ordered Dr. Bernhard Lösener and Franz

Albrecht Medicus of the Interior Ministry to start drafting antisemitic

laws for Hitler to bring to the floor of the Reichstag. On 15 September, Hitler presented two laws — known as the Nuremberg Laws — before the Reichstag. The laws banned marriage between non - Jewish and Jewish Germans, and

forbade the employment of non - Jewish women under the age of 45 in Jewish

households. The laws deprived so-called "non - Aryans" of the benefits of

German citizenship.

In March 1936 Hitler reoccupied the demilitarized zone in the Rhineland, in violation the Versailles treaty. Hitler sent troops to Spain to support General Franco after receiving an appeal for help in July 1936. At the same time, Hitler continued his efforts to create an Anglo - German alliance.

In August 1936, in response to a growing economic crisis caused by his rearmament efforts, Hitler issued a memorandum ordering Hermann Göring to carry out a Four Year Plan to have Germany ready for war within the next four years. The "Four - Year Plan Memorandum" laid out an imminent all-out struggle between "Judeo - Bolshevism" and German National Socialism, which in Hitler's view required a committed effort of rearmament regardless of the economic costs.

On 25 October 1936 Count Galeazzo Ciano, foreign minister of Benito Mussolini's government, declared an axis between Germany and Italy, and on 25 November, Germany signed the Anti - Comintern Pact with Japan. Britain, China, Italy, and Poland were also invited to join the Anti - Comintern Pact, but only Italy signed in 1937. By late 1937 Hitler had abandoned his dream of an Anglo - German alliance, blaming "inadequate" British leadership.

On 5 November 1937 Hitler held a secret meeting at the Reich Chancellery with his war and foreign ministers and military chiefs. As recorded in the Hossbach Memorandum, Hitler stated his intention of acquiring Lebensraum ("living space") for the German people, and ordered preparations for war in the east, which would commence no later than 1943. Hitler stated that the conference minutes were to be regarded as his "political testament" in the event of his death. Hitler said that the crisis of the German economy had reached a point that a severe decline in living standards in Germany could only be stopped by a policy of military aggression — seizing Austria and Czechoslovakia. Hitler urged quick action, before Britain and France obtained a permanent lead in the arms race.

In early 1938, in the wake of the Blomberg – Fritsch Affair,

Hitler asserted control of the military - foreign policy apparatus and

the abolition of the War Ministry and its replacement by the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW). He dismissed Neurath as Foreign Minister on 4 February 1938, and assumed the role and title of the Oberster Befehlshaber der Wehrmacht (supreme commander of the armed forces). From early 1938 onwards, Hitler was carrying out a foreign policy that had war as its ultimate aim.

One of Hitler's central and most controversial ideologies was the concept of what he and his followers termed racial hygiene. Hitler's eugenic policies initially targeted children with physical and developmental disabilities in a program dubbed Action T4.

Hitler's idea of Lebensraum, espoused in Mein Kampf, focused on acquiring new territory for German settlement in Eastern Europe. The Generalplan Ost ("General Plan for the East") called for the population of occupied Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union to be deported to West Siberia, used as slave labor, or murdered; the conquered territories were to be colonized by German or "Germanized" settlers. American historian Timothy D. Snyder wrote that:

Hitler imagined a colonial demodernization of the Soviet Union and Poland that would take tens of millions of lives. The Nazi leadership envisioned an eastern frontier to be depopulated and deindustrialized, and then remade as the agrarian domain of German masters. This vision had four parts. First, the Soviet state was to collapse after a lightning victory in summer 1941, just as the Polish state had in summer 1939, leaving the Germans with complete control over Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, western Russia, and the Caucasus. Second, a Hunger Plan would starve to death some thirty million inhabitants of these lands in winter 1941 – 1942, as food was diverted to Germany and western Europe. Third, the Jews of the Soviet Union who survived the starvation, along with Polish Jews and other Jews under German control, were to be eliminated from Europe in a Final Solution. Fourth, a Generalplan Ost foresaw the deportation, murder, enslavement, or assimilation of remaining populations, and the resettlement of eastern Europe by German colonists in the years after the victory. ... As it became clear in the second half of 1941 that the war was not going according to plan, Hitler made clear that he wanted a Final Solution to be effected immediately.

Between 1939 and 1945, the Schutzstaffel (SS), assisted by collaborationist governments and recruits from occupied countries, were responsible for the deaths of eleven to fourteen million people, including about six million Jews, representing two - thirds of the Jewish population in Europe. Deaths took place in concentration camps, ghettos, and through mass executions. Many victims of the Holocaust were gassed to death, whereas others died of starvation or disease while working as slave laborers.

Hitler's policies also resulted in the killings of Poles and Soviet prisoners of war, communists and other political opponents, homosexuals, Roma, the physically and mentally disabled, Jehovah's Witnesses, Adventists, and trade unionists. One of the largest centers of mass killing was the extermination camp complex of Auschwitz - Birkenau. Hitler never appeared to have visited the concentration camps and did not speak publicly about the killings.

The Holocaust (the "Endlösung der jüdischen Frage" or "Final Solution of the Jewish Question") was organized and executed by Heinrich Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich. The records of the Wannsee Conference — held on 20 January 1942 and led by Reinhard Heydrich, with fifteen senior Nazi officials (including Adolf Eichmann) participating — provide the clearest evidence of the systematic planning for the Holocaust. On 22 February Hitler was recorded saying to his associates, "we shall regain our health only by eliminating the Jews".

Although no specific order from Hitler authorizing the mass killings has surfaced, he approved the Einsatzgruppen, killing squads that followed the German army through Poland and Russia, and he was well informed about their activities. During interrogations by Soviet intelligence officers declassified over fifty years later, Hitler's valet, Heinz Linge, and his adjutant, Otto Günsche, stated that Hitler had a direct interest in the development of gas chambers.

In February 1938, on the advice of his newly appointed Foreign Minister, the strongly pro - Japanese Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler ended the Sino - German alliance with the Republic of China to instead enter into an alliance with the more modern and powerful Japan. Hitler announced German recognition of Manchukuo, the Japanese occupied state in Manchuria, and renounced German claims to their former colonies in the Pacific held by Japan. Hitler ordered an end to arms shipments to China, and recalled all German officers working with the Chinese Army. In retaliation, Chinese General Chiang Kai-shek cancelled

all Sino - German economic agreements, depriving the Germans of many

Chinese raw materials, though they did continue to ship tungsten, a key metal in armaments production, through to 1939.

On 12 March 1938 Hitler declared unification of Austria with Nazi Germany in the Anschluss. Hitler then turned his attention to the ethnic German population of the Sudetenland district of Czechoslovakia.

On 28 – 29 March 1938 Hitler held a series of secret meetings in Berlin with Konrad Henlein of the Sudeten Heimfront (Home Front), the largest of the ethnic German parties of the Sudetenland. Both men agreed that Henlein would demand increased autonomy for Sudeten Germans from the Czechoslovakian government, thus providing a pretext for German military action against Czechoslovakia. In April 1938 Henlein told the foreign minister of Hungary that "whatever the Czech government might offer, he would always raise still higher demands ... he wanted to sabotage an understanding by all means because this was the only method to blow up Czechoslovakia quickly". In private, Hitler considered the Sudeten issue unimportant; his real intention was a war of conquest against Czechoslovakia.

In April 1938 Hitler ordered the OKW to prepare for Fall Grün ("Case Green"), the code name for an invasion of Czechoslovakia. As a result of intense French and British diplomatic pressure, on 5 September 1938 Czechoslovakian President Edvard Beneš unveiled

the "Fourth Plan" for constitutional reorganisation of his country,

which agreed to most of Henlein's demands for Sudeten autonomy. Henlein's Heimfront responded

to Beneš' offer with a series of violent clashes with the

Czechoslovakian police that led to the declaration of martial law in

certain Sudeten districts.

Germany was dependent on imported oil; a confrontation with Britain over the Czechoslovakian dispute could curtail Germany's oil supplies. Hitler called off Fall Grün, originally planned for 1 October 1938. On 29 September 1938 Hitler, Neville Chamberlain, Édouard Daladier, and Benito Mussolini attended a one day conference in Munich that led to the Munich Agreement, which handed over the Sudetenland districts to Germany.

Chamberlain was satisfied with the Munich conference, calling the outcome "peace for our time", while Hitler was angered about the missed opportunity for war in 1938. Hitler expressed his disappointment over the Munich Agreement in a speech on 9 October 1938 in Saarbrücken. In

Hitler's view, the British brokered peace, although favorable to the

ostensible German demands, was a diplomatic defeat which spurred

Hitler's intent of limiting British power to pave the way for the

eastern expansion of Germany. As a result of the summit, Hitler was selected Time magazine's Man of the Year for 1938.

In late 1938 and early 1939, the continuing economic crisis caused by the rearmament efforts forced Hitler to make major defence cuts. On 30 January 1939 Hitler made an "Export or die" speech, calling for a German economic offensive to increase German foreign exchange holdings to pay for raw materials such as high grade iron needed for military weapons.

One thing I should like to say on this day which may be memorable for others as well for us Germans: In the course of my life I have very often been a prophet, and I have usually been ridiculed for it. During the time of my struggle for power it was in the first instance the Jewish race which only received my prophecies with laughter when I said I would one day take over the leadership of the State, and that of the whole nation, and that I would then among many other things settle the Jewish problem. Their laughter was uproarious, but I think that for some time now they have been laughing on the other side of the face. Today I will be once more the prophet. If the international Jewish financiers outside Europe should succeed in plunging the nations once more into a world war, then the result will not be the bolshevisation of the earth, and thus the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe!

— Adolf Hitler, address to German parliament, 30 January 1939

On 15 March 1939, in violation of the Munich accord and possibly as a result of the deepening economic crisis requiring additional assets, Hitler ordered the Wehrmacht to invade Prague, and from Prague Castle proclaimed Bohemia and Moravia a German protectorate.

In private discussions in 1939, Hitler described Britain as the main enemy

that had to be defeated. In his view, Poland's obliteration as a

sovereign nation was a necessary prelude to that goal. The eastern flank

would be secured, and land would be added Germany's Lebensraum. Hitler wanted Poland to become either a German satellite state or be otherwise neutralized to secure the Reich's eastern flank, and to prevent a possible British blockade. Initially,

Hitler favored the idea of a satellite state; this was rejected by the

Polish government. Therefore, Hitler decided to invade Poland; he made

this the main German foreign policy goal of 1939. Hitler

was offended by the British "guarantee" of Polish independence issued

on 31 March 1939, and told his associates that "I shall brew them a

devil's drink". In a speech in Wilhelmshaven for the launch of the battleship Tirpitz on 1 April 1939, Hitler first threatened to denounce the Anglo - German Naval Agreement if the British persisted with their guarantee of Polish independence, which he perceived as an "encirclement" policy. On 3 April 1939 Hitler ordered the military to prepare for Fall Weiss (Case White), the plan for a German invasion on 25 August 1939. In a speech before the Reichstag on 28 April 1939 Hitler renounced both the Anglo - German Naval Agreement and the German – Polish Non - Aggression Pact.

In August 1939 Hitler told his generals that his original plan for 1939

was to "... establish an acceptable relationship with Poland in order

to fight against the West". Since Poland refused to become a German

satellite, Hitler believed his only option was the invasion of Poland.

Hitler was initially concerned that a military attack against Poland could result in a premature war with Britain. However, Hitler's foreign minister — and former Ambassador to London — Joachim von Ribbentrop assured him that neither Britain nor France would honor their commitments to Poland, and that a German – Polish war would only be a limited regional war. Ribbentrop claimed that in December 1938 the French foreign minister, Georges Bonnet, had stated that France considered Eastern Europe as Germany's exclusive sphere of influence; Ribbentrop showed Hitler diplomatic cables that supported his analysis. The German Ambassador in London, Herbert von Dirksen, supported Ribbentrop's analysis with a dispatch in August 1939, reporting that Chamberlain knew "the social structure of Britain, even the conception of the British Empire, would not survive the chaos of even a victorious war", and so would back down. Accordingly, on 21 August 1939 Hitler ordered a military mobilization against Poland.

Hitler's plans for a military campaign in Poland in late August or early September required tacit Soviet support. The non - aggression pact (the Molotov - Ribbentrop Pact) between Germany and the Soviet Union, led by Joseph Stalin, included secret protocols with an agreement to partition Poland between the two countries. In response to the German-Soviet Non - Aggression Pact — and contrary to the prediction of Ribbentrop that the newly formed pact would sever Anglo - Polish ties — Britain and Poland signed the Anglo - Polish alliance on 25 August 1939. This, along with news from Italy that Mussolini would not honor the Pact of Steel, caused Hitler to postpone the attack on Poland from 25 August to 1 September. In the days before the start of the war, Hitler tried to manoeuvre the British into neutrality by offering a non - aggression guarantee to the British Empire on 25 August 1939 and by having Ribbentrop present a last minute peace plan with an impossibly short time limit in an effort to then blame the war on British and Polish inaction.

As a pretext for a military aggression against Poland, Hitler claimed the Free City of Danzig and the right to extraterritorial roads across the Polish Corridor, which Germany had ceded under the Versailles treaty. Despite his concerns over a possible British intervention, Hitler was ultimately not deterred from his aim of invading Poland, and on 1 September 1939 Germany invaded western Poland. In response, Britain and France declared war on Germany on 3 September. This surprised Hitler, prompting him to turn to Ribbentrop and angrily ask "Now what?" France and Britain did not act on their declarations immediately, and on 17 September, Soviet forces invaded eastern Poland.

Poland never will rise again in the form of the Versailles treaty. That is guaranteed not only by Germany, but also ... Russia.

— Adolf Hitler, public speech in Danzig at the end of September 1939.

The fall of Poland was followed by what contemporary journalists dubbed the "Phoney War" or Sitzkrieg ("sitting war"). Hitler instructed the two newly appointed Gauleiters of north - western Poland, Albert Forster and Arthur Greiser, to "Germanize" the area, and promised them "There would be no questions asked" about how this "Germanization was accomplished. Forster had local Poles sign forms stating that they had German blood, and required no further documentation. Greiser carried out a brutal ethnic cleansing campaign on the Polish population in his purview. Greiser complained to Hitler that Forster was allowing thousands of Poles to be accepted as "racial" Germans thus, in Greiser's view, endangering German "racial purity". Hitler told Himmler and Greiser to take up their difficulties with Forster, and not to involve him. Hitler's handling of the Forster – Greiser dispute has been advanced as an example of Ian Kershaw's theory of "Working Towards the Führer": Hitler issued vague instructions and expected his subordinates to work out policies on their own.

Another

dispute broke out between different factions. One side, represented by

Himmler and Greiser championed carrying out ethnic cleansing in Poland,

and another side, represented by Göring and Hans Frank, called for

turning Poland into the "granary" of the Reich. At a conference held at Göring's Karinhall estate

on 12 February 1940, the dispute was initially settled in favor of the

Göring - Frank view of economic exploitation, which ended the

economically disruptive mass expulsions. On

15 May 1940, however, Himmler presented Hitler with a memo entitled

"Some Thoughts on the Treatment of Alien Population in the East", which

called for expulsion of the entire Jewish population of Europe into

Africa and reducing the remainder of the Polish population to a

"leaderless class of laborers". Hitler called Himmler's memo "good and correct"; he

scuttled the so-called Karinhall agreement and implemented the

Himmler – Greiser viewpoint as German policy for the Polish population.

Hitler commenced building up military forces on Germany's western border, and in April 1940, German forces invaded Denmark and Norway. In May 1940, Hitler's forces attacked France, and conquered Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Belgium. These victories prompted Mussolini to have Italy join forces with Hitler on 10 June 1940. France surrendered on 22 June 1940.

Britain, whose forces were forced to leave France by sea from Dunkirk, continued to fight alongside other British dominions in the Battle of the Atlantic. Hitler made peace overtures to the British, now led by Winston Churchill, and when these were rejected Hitler ordered bombing raids on the United Kingdom. Hitler's prelude to a planned invasion of the UK were widespread aerial attacks in the Battle of Britain on Royal Air Force airbases and radar stations in South - East England. However, the German Luftwaffe failed to defeat the Royal Air Force.

On 27 September 1940 the Tripartite Pact was signed in Berlin by Saburō Kurusu of Imperial Japan, Hitler, and Italian foreign minister Ciano. The agreement was later expanded to include Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria. They were collectively known as the Axis powers.

The purpose of the pact was to deter the United States from supporting

the British. By the end of October 1940, air superiority for the

invasion Operation Sea Lion could not be achieved, and Hitler ordered the nightly air raids of British cities, including London, Plymouth, and Coventry.

In the Spring of 1941, Hitler was distracted from his plans for the East by military activities in North Africa, the Balkans, and the Middle East. In February, German forces arrived in Libya to bolster the Italian presence. In April, Hitler launched the invasion of Yugoslavia, quickly followed by the invasion of Greece. In May, German forces were sent to support Iraqi rebel forces fighting against the British and to invade Crete. On 23 May, Hitler released Führer Directive No. 30.

A major historical debate about Hitler's foreign policy preceding the war in 1939 centers on two contrasting explanations: one, by the Marxist historian Timothy Mason, suggests that a structural economic crisis drove Hitler into a "flight into war", while another, by economic historian Richard Overy, explains Hitler's actions with non - economic motives. Historians such as William Carr, Gerhard Weinberg, and Kershaw have argued that a non - economic reason for Hitler's rush to war was Hitler's morbid and obsessive fear of an early death, and hence his feeling that he did not have long to accomplish his work.

On

22 June 1941, contravening the Hitler - Stalin non - aggression pact of

1939, three million German troops attacked the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa. The invasion seized a huge area, including the Baltic states, Belarus, and Ukraine. However, the German advance was stopped barely short of Moscow in December 1941 by the Russian Winter and fierce Soviet resistance.

Some historians, such as Andreas Hillgruber, have argued that Operation Barbarossa was merely one stage of Hitler's Stufenplan (stepwise plan) for world conquest, which Hitler may have formulated in the 1920s. Others, such as John Lukacs, suggest that Hitler did not have a Stufenplan, and that the invasion of the Soviet Union was an ad hoc move in response to Britain's refusal to surrender. Lukacs argues that Churchill had hoped that the Soviet Union might enter the war on the Allied side, and so to dash this hope and force a British surrender, Hitler had started Operation Barbarossa. On the other hand, Klaus Hildebrand has maintained that both Stalin and Hitler had planned to attack each other in 1941. Soviet troop concentrations on its western border in the spring of 1941 may have prompted Hitler to engage in a Flucht nach vorn ("flight forward"), to get in front of an inevitable conflict. Viktor Suvorov, Ernst Topitsch, Joachim Hoffmann, Ernst Nolte, and David Irving have argued that the official reason for Barbarossa given by the German military was the real reason — a preventive war to avert an impending Soviet attack scheduled for July 1941. This theory, however, has been faulted; American historian Gerhard Weinberg once compared the advocates of the preventive war theory to believers in "fairy tales".

The Wehrmacht invasion of the Soviet Union reached its peak on 2 December 1941, when the 258th Infantry Division advanced to within 15 miles (24 km) of Moscow, close enough to see the spires of the Kremlin. However, they were not prepared for the harsh conditions of the Russian winter, and Soviet forces drove back German troops over 320 kilometres (200 mi).

On 7 December 1941 Japan attacked Pearl Harbor,

Hawaii. Four days later, Hitler's formal declaration of war against the

United States officially engaged him in war against a coalition that

included the world's largest empire (the British Empire), the world's

greatest industrial and financial power (the United States), and the

world's largest army (the Soviet Union).

On 18 December 1941 Himmler met with Hitler, and in response to Himmler's question "What to do with the Jews of Russia?", Hitler replied "als Partisanen auszurotten" ("exterminate them as partisans"). Israeli historian Yehuda Bauer has commented that the remark is probably as close as historians will ever get to a definitive order from Hitler for the genocide carried out during the Holocaust.

In late 1942 German forces were defeated in the second battle of El Alamein, thwarting Hitler's plans to seize the Suez Canal and the Middle East. In February 1943 the Battle of Stalingrad ended with the destruction of the German 6th Army. Thereafter came the Battle of Kursk. Hitler's military judgment became increasingly erratic, and Germany's military and economic position deteriorated along with Hitler's health. Kershaw and others believe that Hitler may have suffered from Parkinson's disease. Syphilis has also been suspected as a cause of at least some of his symptoms.

Following the allied invasion of Sicily (Operation Husky) in 1943, Mussolini was deposed by Pietro Badoglio,

who surrendered to the Allies. Throughout 1943 and 1944, the Soviet

Union steadily forced Hitler's armies into retreat along the Eastern Front. On 6 June 1944 the Western Allied armies landed in northern France in what was one of the largest amphibious operations in history, Operation Overlord.

As a result of these significant setbacks for the German army, many of

its officers concluded that defeat was inevitable and that Hitler's

misjudgement or denial would drag out the war and result in the complete destruction of the country. Several high profile assassination attempts against Hitler occurred during this period.

During the period of 1939 – 1945 there were 17 attempts or plans to assassinate Hitler, some of which proceeded to significant degrees. The best known attempt on Hitler's life came from within Germany during World War II and was at least partly driven by the increasing prospect of a German defeat in the war.

In July 1944, in the Operation Valkyrie or 20 July plot, Claus von Stauffenberg planted a bomb in one of Hitler's headquarters, the Wolfsschanze (Wolf's Lair) at Rastenburg.

Hitler narrowly survived because someone had unknowingly pushed the

briefcase that contained the bomb behind a leg of the heavy conference

table. When it exploded, the table deflected much of the blast away from

Hitler. Later, Hitler ordered savage reprisals, resulting in the

executions of more than 4,900 people.

By late 1944, the Red Army had driven the German army back into Western Europe, and the Western Allies were advancing into Germany. After being informed of the twin defeats – Operation Wacht am Rhein and Operation Nordwind – in his Ardennes Offensive at his Adlerhorst command complex, Hitler realised that Germany was about to lose the war. He did not permit an orderly retreat of his armies. His hope, buoyed by the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt on 12 April 1945, was to negotiate peace with America and Britain. Acting on his view that Germany's military failures had forfeited its right to survive as a nation, Hitler ordered the destruction of all German industrial infrastructure before it could fall into Allied hands. Execution of this scorched earth plan was entrusted to arms minister Albert Speer, who quietly disobeyed the order.

On 20 April 1945 Hitler celebrated his 56th birthday in the Führerbunker ("Führer's shelter") below the Reichskanzlei (Reich Chancellery) gardens. By 21 April, Georgi Zhukov's 1st Belorussian Front had broken through the last defences of German General Gotthard Heinrici's Army Group Vistula during the Battle of the Seelow Heights. Facing little resistance, the Soviets advanced into the outskirts of Berlin. In denial about the increasingly dire situation, Hitler placed his hopes on the units commanded by Waffen SS General Felix Steiner, the Armeeabteilung Steiner ("Army Detachment Steiner"). Although "Army Detachment Steiner" was more than a corps, it was less than an army. Hitler ordered Steiner to attack the northern flank of the salient made up of Zhukov's 1st Belorussian Front. At the same time, the German Ninth Army, which had been pushed south of the salient, was ordered to attack northward in a pincer attack.

Late on 21 April, Gotthard Heinrici called Hans Krebs, chief of the Oberkommando des Heeres (Supreme Command of the Army or OKH), to inform him that Hitler's defence plans could not be implemented. Heinrici told Krebs to impress upon Hitler the need to withdraw the 9th Army.

On 22 April, during military conference, Hitler asked about Steiner's offensive. After a long silence, Hitler was told that the attack had never been launched and that the Russians had broken through into Berlin. This news prompted Hitler to ask everyone except Wilhelm Keitel, Hans Krebs, Alfred Jodl, Wilhelm Burgdorf, and Martin Bormann to leave the room. Hitler then launched a tirade against the treachery and incompetence of his commanders, culminating in Hitler's declaration — for the first time — that the war was lost. Hitler announced that he would stay in Berlin, to direct the defence of the city and then shoot himself.

Before the day ended, Hitler again found fresh hope in a new plan that included General Walther Wenck's Twelfth Army. This new plan had Wenck turn his army – currently facing the Americans to the west – and attack towards the east to relieve Berlin. The Twelfth Army was to link up with the Ninth Army and break through to the city. Wenck did attack and made temporary contact with the Potsdam garrison. But the link with the Ninth Army was unsuccessful.

On 23 April, Joseph Goebbels made a proclamation urging the citizens of Berlin to courageously defend the city. Also on 23 April, Göring sent a telegram from Berchtesgaden in Bavaria, arguing that since Hitler was cut off in Berlin, he, Göring, should assume leadership of Germany. Göring set a time limit, after which he would consider Hitler incapacitated. Hitler responded angrily by having Göring arrested, and when writing his will on 29 April, he removed Göring from all his positions in the government. Hitler appointed General der Artillerie Helmuth Weidling as the commander of the Berlin Defence Area, replacing Lieutenant General (Generalleutnant) Helmuth Reymann and Colonel (Oberst) Ernst Kaether. Hitler appointed Waffen - SS Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke the Battle Commander ("Kommandant") for the defence of the government district (Zitadelle sector) that included the Reich Chancellery and Führerbunker.

On 27 April, Berlin became completely cut off from the rest of Germany. As the Soviet forces closed in, Hitler's followers urged him to flee to the mountains of Bavaria to make a last stand in the national redoubt. However, Hitler was determined to either live or die in the capital.

On

28 April, Hitler discovered that Himmler was trying to discuss

surrender terms with the Western Allies (through the Swedish diplomat

Count Folke Bernadotte). Hitler ordered Himmler's arrest and had Hermann Fegelein (Himmler's SS representative at Hitler's HQ in Berlin) shot. Adding

to Hitler's woes was Wenck's report that his Twelfth Army had been

forced back along the entire front and that his forces could no longer

support Berlin.

After midnight on 29 April, Hitler married Eva Braun in a small civil ceremony in a map room within the Führerbunker. Antony Beevor stated that after Hitler hosted a modest wedding breakfast with his new wife, he then took secretary Traudl Junge to another room and dictated his last will and testament. Hitler signed these documents at 4:00 am. The event was witnessed and documents signed by Hans Krebs, Wilhelm Burgdorf, Joseph Goebbels, and Martin Bormann. Hitler then retired to bed. That afternoon, Hitler was informed of the assassination of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, which presumably increased his determination to avoid capture.

On 30 April 1945, after intense street - to - street combat, when Soviet troops were within a block or two of the Reich Chancellery, Hitler and Braun committed suicide; Braun bit into a cyanide capsule and Hitler shot himself with his 7.65 mm Walther PPK pistol. Hitler had at various times contemplated suicide, and the Walther was the same pistol that his niece, Geli Raubal, had used in her suicide in 1931. The lifeless bodies of Hitler and Eva Braun were carried up the stairs and through the bunker's emergency exit to the bombed out garden behind the Reich Chancellery, where they were placed in a bomb crater and doused with petrol. The corpses were set on fire and the Red Army shelling continued.

On 2 May, Berlin surrendered, and there were conflicting reports about what happened to Hitler's remains. Records in the Soviet archives — obtained after the fall of the Soviet Union — showed that the remains of Hitler, Eva Braun, Joseph and Magda Goebbels, the six Goebbels children, General Hans Krebs, and Hitler's dogs, were repeatedly buried and exhumed. On 4 April 1970 a Soviet KGB team with detailed burial charts secretly exhumed five wooden boxes which had been buried at the SMERSH facility in Magdeburg. The remains from the boxes were thoroughly burned and crushed, after which the ashes were thrown into the Biederitz river, a tributary of the nearby Elbe.

According

to the Russian Federal Security Service, a fragment of human skull

stored in its archives and displayed to the public in a 2000 exhibition

came from Hitler's remains. However, the authenticity of the skull

fragment was challenged by historians and researchers, and

DNA analysis conducted in 2009 showed the skull fragment to be that of a

woman. Analysis of the sutures between the skull plates indicated that

it belonged to a 20 – 40 year old individual.

Hitler's policies and orders resulted in the death of approximately 40 million people, including about 27 million in the Soviet Union. The actions of Hitler, and Hitler's ideology, Nazism, are almost universally regarded as gravely immoral. Historians, philosophers, and politicians have often applied the word evil to describe Hitler's ideology and its outcomes. Historical and cultural portrayals of Hitler in the west are overwhelmingly condemnatory. In Germany and Austria, the denial of the Holocaust and the display of Nazi symbols such as swastikas are prohibited by law.

Outside of Hitler's birthplace in Braunau am Inn, Austria, the Memorial Stone Against War and Fascism is engraved with the following message:

| Loosely translated, it reads: |

Following World War II, the toothbrush moustache fell out of favour in the West because of its strong association with Hitler, which earned it the nickname "Hitler moustache". The use of the name "Adolf" also declined in post war years.

Hitler and his legacy are occasionally described in more neutral or even favorable terms. Former Egyptian President Anwar El Sadat spoke

of his 'admiration' of Hitler in 1953, when he was a young man, but it

is possible that Sadat's views were shaped mainly by his anti - British

sentiments. Bal Thackeray, leader of the right wing Hindu nationalist Shiv Sena party in the Indian state of the Maharashtra, declared in 1995 that he was an admirer of Hitler. German historian Friedrich Meinecke said that Hitler's life "is one of the great examples of the singular and incalculable power of personality in historical life".

Hitler's parents were Roman Catholics, but after leaving home he never attended Mass or received the sacraments. Hitler favored aspects of Protestantism that suited his own views. However, he adopted some elements of the Catholic Church's hierarchical organization, liturgy, and phraseology in his politics. After his move to Germany, where Catholic and Protestant churches are largely financed through a church tax, Hitler did not leave his church, leading the historian Richard Steigmann - Gall to conclude that Hitler "can be classified as Catholic", but that "nominal church membership is a very unreliable gauge of actual piety in this context."

In public, Hitler often praised Christian heritage and German Christian culture, and professed a belief in an "Aryan" Jesus Christ — a Jesus who fought against the Jews. In

his speeches and publications, Hitler spoke of his interpretation of

Christianity as a central motivation for his antisemitism, stating that

"As a Christian I have no duty to allow myself to be cheated, but I have

the duty to be a fighter for truth and justice." In

private, Hitler was more critical of traditional Christianity,

considering it a religion fit only for slaves; he admired the power of

Rome but maintained a severe hostility towards its teaching. Hitler's critical views on Catholicism resonated with Streicher's contention that the Catholic establishment was allying itself with the Jews. In light of these private statements, for John S. Conway and

many other historians, it is beyond doubt that Hitler held a

"fundamental antagonism" towards the Christian churches. However, some

researchers have questioned the authenticity of Hitler's private

statements; for instance, Hermann Rauschning's Hitler speaks is considered by most historians to be an invention.

In political relations with the churches in Germany, Hitler adopted a strategy "that suited his immediate political purposes". According to a US Office of Strategic Services report, Hitler had a general plan, even before his rise to power, to destroy the influence of Christian Churches within the Reich. The report titled "The Nazi Master Plan" stated, "the destruction of Christianity was explicitly recognised as a purpose of the National Socialist movement" from the start, but "considerations of expedience made it impossible" to express this extreme position publicly. His intention, according to Alan Bullock, was to wait until the war was over to destroy the influence of Christianity.

Hitler for a time advocated a form of the Christian faith he called "Positive Christianity", a belief system purged of what he objected to in orthodox Christianity, and featuring racist elements. By 1940, however, Hitler had abandoned advocating even the syncretist idea of a positive Christianity. Hitler maintained that the "terrorism in religion is, to put it briefly, of a Jewish dogma, which Christianity has universalized and whose effect is to sow trouble and confusion in men's minds."

Hitler articulated his view on the relationship between religion and national identity as "We do not want any other god than Germany itself. It is essential to have fanatical faith and hope and love in and for Germany".

Hitler expressed admiration for the Muslim military tradition. Stanley G. Payne wrote:

Hitler generally had a high opinion of Islam and once proclaimed it the best of religions because of its theological simplicity and emphasis on holy war. ... Hitler expressed regret that Islam had not swept over all western Europe. Had it replaced Christianity in Germany, the innate racial superiority of the Germans in conjunction with Islam would have enabled them to conquer much of the world during the Middle Ages.

Hitler's health has frequently been the subject of speculation. It has been suggested that he suffered from irritable bowel syndrome, skin lesions, irregular heartbeat, Parkinson's disease, syphilis, tinnitus, and Asperger syndrome. Hitler had dental problems — his personal dentist, Hugo Blaschke, fitted a large dental bridge to Hitler's upper jaw in 1933, and in 1944, Blaschke removed the left rear section of the bridge to treat an infection of Hitler's gums that coincided with a sinus infection.

Hitler followed a vegetarian diet, and never ate meat. At social events Hitler sometimes gave graphic accounts of the slaughter of animals in an effort to make his dinner guests shun meat. A fear of cancer (from which his mother died) is the most widely cited reason for Hitler's dietary habits. An antivivisectionist, Hitler may have followed his selective diet out of a profound concern for animals. Martin Bormann had a greenhouse constructed near the Berghof (near Berchtesgaden) to ensure a steady supply of fresh fruit and vegetables for Hitler throughout the war.

Hitler was a non - smoker and promoted aggressive anti - smoking campaigns throughout Germany. (Anti - tobacco movement in Nazi Germany.) Hitler strongly despised alcohol.