<Back to Index>

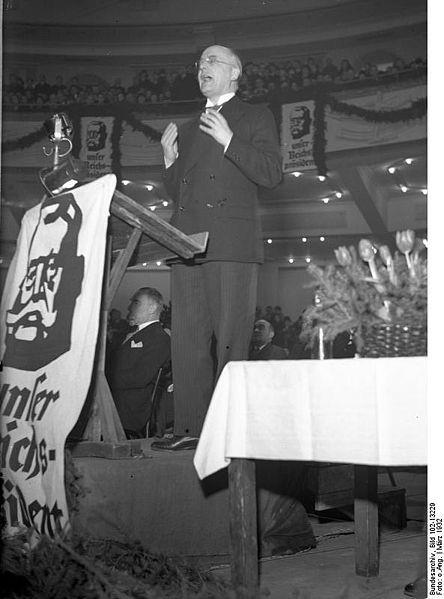

- Chancellor of Germany Heinrich Brüning, 1885

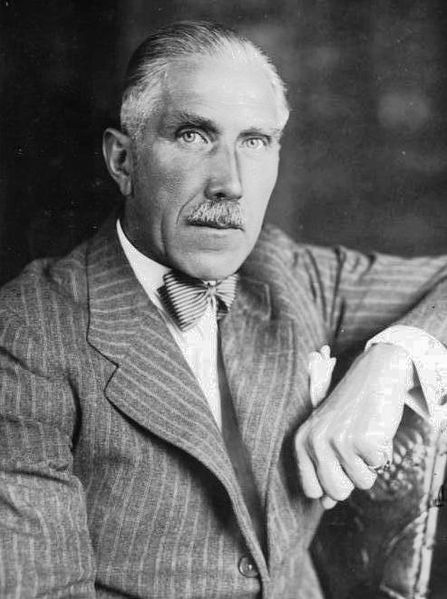

- Chancellor of Germany Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen zu Köningen, 1879

- Chancellor of Germany Kurt von Schleicher, 1882

PAGE SPONSOR

Heinrich Brüning (26 November 1885 – 30 March 1970) was Chancellor of Germany from 1930 to 1932, during the Weimar Republic. He was the longest serving Chancellor of the Weimar Republic, and remains a controversial figure in German politics.

During much of Brüning's tenure, he based his administration on presidential emergency decree ("Notverordnung").

Brüning coined the term "authoritative (or authoritarian)

democracy" to describe this form of government based on the cooperation

of the president and toleration of the parliament.

Born in Münster in Westphalia, Brüning lost his father when he was one year old and thus his elder brother Hermann Joseph played a major part in his upbringing. Although raised a devout Catholic, Brüning was also influenced by Lutheranism's concept of duty, since the Münster region was home to both Catholics, who formed a majority (especially in the western part) and some Prussian influenced Protestants.

After graduating from Gymnasium Paulinum he first tended towards the legal profession, but then studied Philosophy, History, German and Political Science at Strasbourg, the London School of Economics and Bonn, where he achieved his doctorate in national economy. One of his professors at Strasbourg, who had a major influence on Brüning was the historian Friedrich Meinecke.

After receiving his doctorate in 1915, he volunteered for the infantry. He served in World War I from 1915 to 1918 as a lieutenant in the infantry regiment No. 30, "Werder Graf", rising to company commander by the end of the war, and earned an Iron Cross second and first class.

He did not approve of the German Revolution of 1918 – 1919, which saw the establishment of the Weimar government, and in its aftermath he decided not to pursue his academic career further, but preferred helping those who had fallen into trouble. He collaborated with the social reformer Carl Sonnenschein and worked in the "Secretariat for social student work", helping demobilized soldiers to study and work. After six months he entered the Prussian welfare department and became a close associate of the minister Adam Stegerwald. Stegerwald, also leader of the Christian trade unions, made him chief executive of the unions in 1920, a post Brüning retained until 1930. In 1923 he was actively involved in organizing the passive resistance in the "Ruhrkampf". As the editor of the union newspaper Der Deutsche (The German), he advocated a "social popular state" and "Christian democracy," based on the ideas of Catholic Corporatism.

He also joined the Center Party and in 1924 he was elected to the Reichstag, representing Breslau. In parliament, Brüning quickly made a name for himself as a financial expert and managed to push though the "lex Brüning", which restricted the wage tax. He always insisted on a disciplined, thrifty approach towards money, criticizing both an increase of civil service salaries and the luxury of profiteers. Recognized for his expertise, this personal reserve and calmness hampered dealing with him on a personal level. From 1928 to 1930, he was a member of the Prussian parliament and, in 1929, he was elected chairman of the Center Party's faction in the Reichstag.

In 1930, when the grand coalition under the Social Democrat Hermann Müller collapsed, Brüning was appointed chancellor on 29 March 1930. The government was confronted with the economic crisis caused by the Great Depression.

Brüning disclosed to his associates in the German Labor

Federation that his chief aim as chancellor would be to liberate the

German economy from the burden of continuing to pay war reparations.

This would require an unpopular policy of tight credit and a rollback

of all wage and salary increases. Brüning's financial and economic

acumen combined with his openness to social questions made him a

candidate for chancellor and his service as a front officer made him

acceptable to President Paul von Hindenburg.

The Reichstag rejected his measures within a month. President Hindenburg, already bent on reducing the influence of the Reichstag, saw this event as the "failure of parliament" and with Brüning's consent called for new elections. These elections cost the parties of the grand coalition their majority and brought gains to both Communists and National Socialists. This left Brüning without any hope of reforging a party coalition and forced him to base his administration on the presidential emergency decree ("Notverordnung") of Article 48 of the Constitution, circumventing parliament and the informal toleration of this practice by the parties. Brüning coined the term "authoritative (or authoritarian) democracy" to describe this form of government based on the cooperation of the president and parliament.

Hindenburg desired to base the government on the parties of the right but the right wing German National People's Party (DNVP) refused to support Brüning's government. To the president's dismay, Brüning had to rely on his own Center Party, the only party that fully supported him, and the toleration of the Social Democrats.

Brüning's measures were implemented in the summer by presidential decree and made him extremely unpopular among the lower and middle classes. As unemployment continued to rise, his cuts in welfare and reductions of wages combined with rising prices and taxes, increased misery among workers and the unemployed. This gave rise to the quote: "Brüning verordnet Not!", alluding to his measures being implemented by "Notverordnung".

These effects undermined the support of the Social Democrats for the government and the liberal and conservative cabinet members favored opening the government to the right. President Hindenburg, pushed by his camarilla and military chief Kurt von Schleicher, also advocated such a move and insisted on a cabinet reshuffle and especially the resignation of ministers Wirth and Guérard, both from the Center Party.

The president's wishes also hampered the government's resolution in combating the extremist parties and their respective paramilitary organizations. While the chancellor and president agreed that the Communists' and Nazis' brutality, intolerance and demagogy rendered them unfit for government, Brüning believed the government was strong enough to steer Germany through the crisis without the support of the Nazis. Nonetheless, he negotiated with Hitler about toleration or a formal coalition, without yielding to the Nazis any position of power or full support by presidential decree. Because of these reservations the negotiations came to nothing and as street violence rose to new heights in April 1932, Brüning had both the communist "Rotfrontkämpferbund" and the Nazi Sturmabteilung banned. The unfavorable reactions of right wing circles to that move further undermined Hindenburg's support for Brüning.

Even before then, Brüning had agonized over how to stem the growing Nazi tide, especially since Hindenburg could not be expected to survive another full term as president should he choose to run again. If Hindenburg were to die in office, Hitler would be a strong favorite to succeed him. By the end of 1931, Brüning thought he had hit upon a solution — restoring the Hohenzollern monarchy. He intended to persuade the Reichstag and Reichsrat to cancel the 1932 presidential election and simply extend Hindenburg's term by a two - thirds vote in both chambers. He would then have parliament proclaim a monarchy, with Hindenburg as regent. On Hindenburg's death, one of Crown Prince William's sons would be invited to assume the throne. Unlike the old German Empire, the restored monarchy would have been a British style constitutional monarchy in which real power would have rested with the legislature. All of the major parties except the Communists were at least willing to give Brüning's plan some support, seeing this as the last real chance of stopping Hitler. The plan foundered when Hindenburg, an old line monarchist at heart, refused to stand down in favor of anyone except William II. Brüning tried to impress upon him that neither the Social Democrats nor the international community would tolerate any return of William II, and that the Crown Prince would not be acceptable either. This only angered Hindenburg further and he threw Brüning out of his office.

In

the international theatre, Brüning tried to alleviate the burden

of reparation payments and to achieve German equality in the rearmament

question. In 1930, he replied to Aristide Briand's initiative to form a "United States of Europe" by demanding full equality for Germany. In 1931 plans for a customs union between Germany and Austria were shattered by French opposition. In the same year, the Hoover memorandum

postponed reparation payments and in summer 1932, after Brüning's

resignation, his successors could reap the fruits of his policy at the Lausanne conference, which reduced German reparations to a final installment of 3 billion marks. Negotiations over rearmament failed at the 1932 Geneva Conference shortly before his resignation, but in December the "Five powers agreement" accepted Germany's military equality.

Hindenburg was not willing to run for reelection at first but changed his mind. In 1932, Brüning along with virtually the entire German left and center, vigorously campaigned for Hindenburg's reelection, calling him a "venerate historical personality" and "the keeper of the constitution". Hindenburg was re-elected against Hitler but he considered it shameful to be elected by the votes of "Reds" and "Catholes", as he called Social Democrats and the Center Party and compensated for this "shame" by moving further to the right. At the same time, his failing health only increased the influence of the camarilla.

At that time, Brüning was viciously attacked by the Prussian Junkers, led by Elard von Oldenburg - Januschau. They opposed his policies of distributing land to unemployed workers and denounced him as an "Agro - bolshevik" to Hindenburg.

The president asked Brüning to make way by stepping down as chancellor while remaining foreign minister.

Brüning refused to serve as a figurehead for such a right wing

government and announced his cabinet's resignation on 30 May 1932,

"hundred meters before the finish". He sternly rejected all suggestions

to make the president's disloyal behavior public, because he considered

such a move indecent and because he still considered Hindenburg the

"last bulwark" of the German people.

After his resignation, Brüning was invited by Ludwig Kaas to take over the leadership of the Center Party, but the former chancellor declined and asked Kaas to stay. Brüning supported his party's determined opposition to his successor, Franz von Papen, and also of re-establishing a working parliament by cooperation with the National Socialists, negotiating with Gregor Strasser.

After Adolf Hitler became

chancellor on 30 January 1933, Brüning vigorously campaigned

against the new government in the March elections. Later that month, he

was a main advocate for rejecting the Hitler administration's Enabling Act,

calling it the "most monstrous resolution ever demanded of a

parliament." He nonetheless yielded to party discipline and voted in

favor of the bill. Only the Social Democrats voted

against the law. When Kaas was held up in Rome and resigned from his

post as chairman of the Center Party, Brüning was elected chairman

on 6 May. However, Brüning yielded to increasing persecution by the

National Socialist controlled government by dissolving the Center Party

on 6 July.

To escape Hitler's political purges, Brüning fled Germany in 1934 via the Netherlands and settled in the United Kingdom. In 1939, he became professor of political science at Harvard University. He warned the American public about Hitler's plans for war and later about Soviet expansion, but in both cases his advice went unheeded.

In 1947, he returned to Germany and taught at the University of Cologne. He was a critic of Adenauer's policy of Western integration and as he saw no prospect of resuming his political career, he returned to the United States. In 1968, he published "Speeches and Essays".

Brüning died in 1970 in Norwich, Vermont, and was buried in his home town of Münster.

Posthumously, his "Memoirs 1918 – 1934" were published, a source disputed among historians.

Brüning

remains a controversial figure, since it is debated whether he was the

"last bulwark of the Republic" or the "Republic's undertaker", or both.

His intentions certainly were to protect the Republican government, but

his policies also contributed to the gradual demise of the Weimar Republic from

1930 to 1933. Comparing some current leaders to Brüning remains a

sure way to create a highly emotional response in German political discussions.

Lieutenant - Colonel Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen zu Köningen (29 October 1879 – 2 May 1969) was a German nobleman, Roman Catholic monarchist politician, General Staff officer, and diplomat, who served as Chancellor of Germany in 1932 and as Vice - Chancellor under Adolf Hitler in 1933 – 1934. A member of the Catholic Center Party until 1932, he was one of the most influential members of the group of close advisers to President Paul von Hindenburg in the late Weimar Republic. It was largely Papen, believing that Hitler could be controlled once he was in the government, who persuaded Hindenburg to put aside his scruples and approve Hitler as Chancellor in a cabinet not under Nazi Party domination. However, Papen and his allies were quickly marginalized by Hitler and he left the government after the Night of the Long Knives, during which some of his confidants were killed by the Nazis.

Born to a wealthy and noble Roman Catholic family in Werl, Province of Westphalia, son of Friedrich von Papen zu Köningen (1839 – 1906) and wife Anna Laura von Steffens (1852 – 1939), Papen was educated as an officer, including a period as a military attendant in the Kaiser's Palace, before joining the German General Staff in March 1913. He entered diplomatic service in December 1913 as a military attaché to the German ambassador in the United States. He traveled to Mexico (to which he was also accredited) in early 1914 and observed the Mexican Revolution, returning to Washington, D.C. on the outbreak of World War I in August 1914. He married Martha von Boch - Galhau (1880 – 1961) on 3 May 1905.

Papen was expelled from the United States during World War I for alleged complicity in the planning of sabotage such as blowing up U.S. rail lines. On 28 December 1915, he was declared persona non grata after his exposure and recalled to Germany. En route, his luggage was confiscated, and 126 check stubs were found showing payments to his agents. Papen went on to report on American attitudes, to both General Erich von Falkenhayn and Wilhelm II, German Emperor.

In April 1916, a United States federal grand jury issued an indictment against Papen for a plot to blow up Canada's Welland Canal, which connects Lake Ontario to Lake Erie, but Papen was then safely home; he remained under indictment until he became Chancellor of Germany, at which time the charges were dropped. Later in World War I, Papen served as an officer first on the Western Front, from 1917 as an officer on the General Staff in the Middle East, and as a major in the Ottoman army in Palestine.

Papen also served as intermediary between the Irish Volunteers and the German government regarding the purchase and delivery of arms to be used against the British during the Easter Rising of 1916, as well as serving as an intermediary with the Indian nationalists in the Hindu German Conspiracy. Promoted to the rank of lieutenant - colonel, he returned to Germany and left the army at the war's end in 1918.

He entered politics and joined the Catholic Center Party (Zentrum), in which the monarchist Papen formed part of the conservative wing. He was a member of the parliament of Prussia from 1921 to 1932.

In the 1925 presidential elections, he surprised his party by supporting the right wing candidate Paul von Hindenburg over the Center Party's Wilhelm Marx.

He was a member of the "Deutscher Herrenklub" (German Gentlemen's Club) of Arthur Moeller van den Bruck.

On 1 June 1932 he moved from relative obscurity to supreme importance when President Paul von Hindenburg appointed him Chancellor, even though this meant replacing his own party's Heinrich Brüning.

The day before, he had promised party chairman Ludwig Kaas not to accept any appointment. After he broke his pledge, Kaas branded him the "Ephialtes of the Center Party"; Papen forestalled being expelled by leaving the party on 3 June 1932.

The French ambassador in Berlin, André François - Poncet, wrote at the time that Papen's selection by Hindenburg as chancellor "met with incredulity." Papen, the ambassador continued, "enjoyed the peculiarity of being taken seriously by neither his friends nor his enemies. He was reputed to be superficial, blundering, untrue, ambitious, vain, crafty and an intriguer."

The cabinet which Papen formed, with the assistance of General Kurt von Schleicher, was known as the "cabinet of barons" or as the "cabinet of monocles" and was widely regarded with ridicule by Germans. Except from the conservative German National People's Party (DNVP), Papen had practically no support in the Reichstag.

Papen ruled in an authoritarian manner by launching a coup against the center left coalition government of Prussia (the so-called Preußenschlag) and repealing his predecessor's ban on the SA as a way to appease the Nazis, whom he hoped to lure into supporting his government. Riots resulted on the streets of Berlin, as 461 battles between Communists and the SA took place, leading to the loss of 82 lives on both sides. Berlin was put on military shutdown and von Papen sent men to arrest the Prussian authorities, whom he suspected of being in league with the Communists. Thereafter, von Papen declared himself commander of the Prussian region, further weakening the democracy of the Weimar Republic.

Soon afterward, Papen called an election for July 1932 in

hopes of getting a majority in the Reichstag. However, he did not even

come close — in fact, the Nazis gained 123 seats to become the largest

party. When this Reichstag first assembled, Papen obtained in advance

from Hindenburg a decree to dissolve it. He initially did not bring it

along, having received a promise that there would be an immediate

objection to an expected Communist motion

of censure. However, when no one objected, Papen ordered one of his

messengers to get the order. When he demanded the floor in order to read

it, newly elected Reichstag president Göring pretended

not to see him; his Nazis had decided to support the Communist motion.

The censure vote passed overwhelmingly, forcing another election.

In the November 1932 election the Nazis lost seats, but Papen was still unable to get a majority. Papen then decided to try to negotiate with Hitler, but Hitler's reply contained so many conditions that Papen gave up all hope of reaching agreement. Soon afterward, under pressure from Schleicher, Papen resigned on November 17.

Papen held out hope of being reappointed by Hindenburg, fully expecting that the aging President would find Hitler's demands unacceptable. Indeed, when Schleicher suggested on 1 December that he might be able to get support from the Nazis, Hindenburg blanched and told Papen to try to form another government. However, at a cabinet meeting the next day, Papen was informed that there was no way to maintain order against the Nazis and Communists. Realizing that Schleicher was deliberately trying to undercut him, Papen asked Hindenburg to fire Schleicher as defense minister. Instead, Hindenburg told Papen that he was appointing Schleicher as chancellor. Schleicher hoped to establish a broad coalition government by gaining the support of both Nazi and Social Democratic trade unionists.

As it became increasingly obvious that Schleicher would be unsuccessful in his maneuvering to maintain his chancellorship under a parliamentary majority, Papen worked to undermine Schleicher. Along with DNVP leader Alfred Hugenberg, Papen formed an agreement with Hitler under which the Nazi leader would become Chancellor of a coalition government with the Nationalists, and with Papen serving as Vice Chancellor of the Reich and prime minister of Prussia.

On 23 January 1933 Schleicher admitted to President Hindenburg that he had been unable to obtain a majority of the Reichstag, and asked the president to declare a state of emergency. By this time, the elderly Hindenburg had become irritated by the Schleicher cabinet's policies affecting wealthy landowners and industrialists.

Simultaneously, Papen had been working behind the scenes and used his personal friendship with Hindenburg to assure the President that he, Papen, could control Hitler and could thus finally form a government based on the support of the majority of the Reichstag.

Hindenburg

refused to grant Schleicher the emergency powers he sought, and

Schleicher resigned on 28 January. Papen toyed with the idea of

betraying Hitler by ousting him from the cabinet, and becoming

chancellor himself. In the end the President, who had previously vowed

never to allow Hitler to become chancellor ('that Austrian corporal', he

derisively referred to him as) appointed Hitler to the post on 30

January 1933, with von Papen as Vice - Chancellor. The remaining members

of the cabinet were conservatives, with the exception of two Nazis.

At the formation of Hitler's cabinet on 30 January, the Nazis had three cabinet posts (including Hitler) to the conservatives' eight. Additionally, as part of the deal that allowed Hitler to become chancellor, Papen was granted the right to sit in on every meeting between Hitler and Hindenburg. Counting on their majority in the Cabinet and on the closeness between himself and Hindenburg, Papen had anticipated "boxing Hitler in." Papen boasted to intimates that "Within two months we will have pushed Hitler so far in the corner that he'll squeak." To the warning that he was placing himself in Hitler's hands, Papen replied, "You are mistaken. We've hired him."

However, Hitler and his allies instead quickly marginalized Papen and the rest of the cabinet. For example, Hermann Göring had been appointed deputy interior minister of Prussia, but frequently acted without consulting his nominal superior, Papen. Neither Papen nor his conservative allies waged a fight against the Reichstag Fire Decree in late February or the Enabling Act in March.

On 8 April Papen traveled to the Vatican to offer a Reichskonkordat that defined the German state's relationship with the Roman Catholic Church. During Papen's absence, the Nazified Landtag of Prussia elected Göring as prime minister on 10 April.

Conscious of his own increasing marginalization, Papen began covert talks with other conservative forces with the aim of convincing Hindenburg to dismiss Hitler. Of special importance in these talks was the growing conflict between the German military and the paramilitary Sturmabteilung (SA), led by Ernst Röhm.

In

early 1934 Röhm continued to demand that the storm troopers become

the core of a new German army. Many conservatives, including

Hindenburg, felt uneasy with the storm troopers' demands, their lack of

discipline and their revolutionary tendencies.

With the Army command recently having hinted at the need for Hitler to control the SA, Papen delivered an address at the University of Marburg on 17 June 1934 where he called for the restoration of some freedoms, demanded an end to the calls for a "second revolution" and advocated the cessation of SA terror in the streets.

In this "Marburg speech" Papen said that "The government [must be] mindful of the old maxim 'only weaklings suffer no criticism'" and that "No organization, no propaganda, however excellent, can alone maintain confidence in the long run." The speech was crafted by Papen's speech writer, Edgar Julius Jung, with the assistance of Papen's secretary Herbert von Bose and Catholic leader Erich Klausener.

The vice chancellor's bold speech incensed Hitler, and its publication was suppressed by the Propaganda Ministry. Angered by this reaction and stating that he had spoken on behalf of Hindenburg, Papen told Hitler that he was resigning and would inform Hindenburg at once. Hitler knew that accepting the resignation of Hindenburg's long time confidant, especially during a time of tumult, would anger the ailing president. He guessed right; not long afterward Hindenburg gave Hitler an ultimatum — unless he acted to end the state of tension in Germany, Hindenburg would throw him out of office and turn over control of the government to the army.

Two weeks after the Marburg speech, Hitler responded to the armed forces' demands to suppress the ambitions of Röhm and the SA by purging the SA leadership. The purge, known as the Night of the Long Knives, took place between 30 June and 2 July 1934. In the purge, Röhm and much of the SA leadership were murdered. General von Schleicher, who as Chancellor had been scheming with some of Hitler's rivals within the party to separate them from their leader, was gunned down along with his wife. Also Gustav von Kahr, the conservative who had thwarted the Putsch more than ten years earlier, was shot and thrown into a swamp.

Though Papen's bold speech against some of the excesses committed by the Nazis had angered Hitler, Hitler was aware that he could not act directly against the Vice Chancellor without offending Hindenburg. Instead, in the Night of the Long Knives, the Vice Chancellery, Papen's office, was ransacked by the SS, where his associate Herbert von Bose was shot dead at his desk. Another associate, Erich Klausener, was shot dead at his desk at the Ministry of Transportation. Many more were arrested and imprisoned in concentration camps where Jung, amongst others, was shot a few days later. Papen himself was placed under house arrest at his villa with his telephone line cut, though some accounts indicate that this "protective custody" was ordered by Göring, who felt the ex-diplomat could be useful in the future. Other sources suggest that Papen had shared a place with Schleicher on an SS "death list", and that Göring had in fact saved him from the purge by ordering his confinement, possibly unwittingly after personal disputes.

Reportedly

Papen arrived at the Chancellery, exhausted from days in house arrest

without sleep to find the Chancellor seated with other Nazi ministers

around a round table, with no place for him but a hole in the middle, he

insisted on a private audience with Hitler and announced his

resignation, stating; My service to the Fatherland is over! The

following day, Papen's resignation as Vice Chancellor was formally

accepted and publicized, with no successor appointed. With Hindenburg's

death weeks later, the last conservative obstacle to complete Nazi rule

was gone.

Despite the events of the Night of the Long Knives, Papen accepted within a month the assignment from Hitler as German ambassador in Vienna, where Austrian Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss had just been murdered in a failed Nazi coup, which was brutally suppressed.

In Hitler's words, Papen's duty was to restore "normal and friendly relations" between Germany and Austria. Papen also contributed to achieving Hitler's goal of undermining Austrian sovereignty and bringing about the Nazis' long dreamed of Anschluss (unification with Germany). Winston Churchill reports in his book The Gathering Storm (1948) that Hitler appointed Papen for "the undermining or winning over of leading personalities in Austrian politics". Churchill also quotes the U.S. minister in Vienna as saying of Papen "In the boldest and most cynical manner... Papen proceeded to tell me that... he intended to use his reputation as a good Catholic to gain influence with Austrians like Cardinal Innitzer."

Ironically, one of the plots called for Papen's murder by Austrian Nazi sympathizers as a pretext for a retaliatory invasion by Germany.

Though

Papen was dismissed from his mission in Austria on 4 February 1938,

Hitler drafted Papen to arrange a meeting between the German dictator and Austrian Chancellor Kurt von Schuschnigg at Berchtesgaden.

The ultimatum that Hitler presented Schuschnigg, at the meeting on 12

February 1938, led to the Austrian government's capitulation to German

threats and pressure, and paved the way for the Anschluss, which was proclaimed on 13 March 1938.

Papen later served the German government as Ambassador to Turkey from 1939 to 1944. There, he survived a Soviet assassination attempt on 24 February 1942 by agents from the NKVD — a bomb prematurely exploded, killing the bomber and no one else, although Papen was slightly injured.

However, some Soviet sources say that the assassination attempt was in fact the work of one of Nazi Germany's own secret services. Its goal was apparently to disrupt Soviet - Turkish relations and even to push Turkey into declaring war on the Soviet Union and joining Germany.

After Pope Pius XI died in 1939, his successor Pope Pius XII did not renew his honorary title of Papal Chamberlain. As nuncio, the future Pope John XXIII, Angelo Roncalli, was acquainted with Papen in Greece and Turkey during World War II. The German government considered appointing Papen ambassador to the Holy See, but Pope Pius XII, after consulting Konrad von Preysing, Bishop of Berlin, rejected this proposal.

In

August 1944, Papen had his last meeting with Hitler after arriving back

in Germany from Turkey. Here, Hitler awarded Papen the Knight's Cross of the Military Merit Order.

Papen was captured along with his son Franz Jr. by U.S. Army Lt. James E. Watson and members of the 550th Airborne battalion near the end of the war at his home. According to Watson, as he was put into the jeep for his ride into a POW camp, Papen was heard to remark (in English), "I wish this terrible war were over." At that one of his sergeants responded, "So do 11 million other guys!"

Papen was one of the defendants at the main Nuremberg War Crimes Trial. The court acquitted him, stating while he had committed a number of "political immoralities," these actions were not punishable under the "conspiracy to commit crimes against peace" charged in Papen's indictment. He was later sentenced to eight years hard labor by a West German denazification court, but was released on appeal in 1949.

Papen tried unsuccessfully to re-start his political career in the 1950s, and lived at the Castle of Benzenhofen in Upper Swabia.

Pope John XXIII restored his title of Papal Chamberlain on 24 July 1959. Papen was also a Knight of Malta, and was awarded the Grand Cross of the Pontifical Order of Pius IX.

Papen published a number of books and memoirs, in which he defended his policies and dealt with the years 1930 to 1933 as well as early western Cold War politics. Papen praised the Schuman Plan as "wise and statesmanlike" and believed in the economic and military unification and integration of Western Europe.

Franz von Papen died in Obersasbach, West Germany, on 2 May 1969 at the age of 89.

Kurt von Schleicher (7 April 1882 – 30 June 1934) was a German general and the last Chancellor of Germany during the era of the Weimar Republic. Seventeen months after his resignation, he was assassinated by order of his successor, Adolf Hitler, in the Night of the Long Knives.

Schleicher was born in Brandenburg an der Havel, the son of a Prussian officer and a shipowner′s daughter. He entered the German Army in 1900 as a Leutnant after graduating from a cadet training school. In his early years, Schleicher made two friendships which later were to play an important role in his life. As a cadet, Schleicher befriended Franz von Papen, and later on as an officer in the Third Guards Regiment, he befriended Oskar von Hindenburg. During World War I, he served on the staff of Wilhelm Groener, who became Schleicher′s patron. In December 1918, Schleicher delivered an ultimatum to Friedrich Ebert on behalf of Paul von Hindenburg demanding that the German provisional government either allow the Army to crush the Spartacus League or the Army would do that task themselves. During the ensuing talks with the German cabinet, Schleicher was able to get permission to allow the Army to return to Berlin. On December 23, 1918, a group of Red sailors seemed set to storm and take over the Provisional government when the sailors cut all telephone lines from the Chancellor′s office to the War Ministry except for a secret one. When Ebert used the secret line to call the War Ministry, it was Schleicher who took the call. In exchange for agreeing to send help to the government, Schleicher was able to secure Ebert′s assent to the Army being allowed to maintain its political autonomy. When Gustav Noske was appointed Defense Minister on December 27, 1918, both Groener and his protégé Schleicher established excellent working relations with the new minister. To deal with the problem of the lack of loyal troops, Schleicher helped to found the Freikorps in early January 1919.

In the early 1920s, Schleicher had emerged as a leading protégé of General Hans von Seeckt, who often gave Schleicher sensitive assignments. In the spring of 1921, Seeckt created a secret group within the Reichswehr known as Sondergruppe R whose task was to work with the Red Army in their common struggle against the international system established by the Treaty of Versailles. Schleicher was a leading member of Sondergruppe R, and it was he who worked out the arrangements with Leonid Krasin for German aid to the Soviet arms industry. In September 1921, at a secret meeting in Schleicher′s appartment, the details of an arrangement were reached in which German financial and technological aid for building the Soviet arms industry were exchanged for Soviet support in helping Germany circumvent the disarmament clauses of the Treaty of Versailles. Schleicher created several dummy corporations, most notably the GEFU (Gesellschaft zur Förderung gewerblicher Unternehmungen - Company for the promotion of industrial enterprise) that funnelled 75 million Reichmarks into the Soviet arms industry. The GEFU founded factories in the Soviet Union for the production of aircraft, tanks, artillery shells and poison gas. The arms contracts of GEFU in the Soviet Union ensured that Germany did not fall behind in military technology in the 1920s despite being disarmed by Versailles, and laid the covert foundations in the 1920s for the overt rearmament of the 1930s. At the same time, a team from Sondergruppe R comprising Schleicher, Eugen Ott, Fedor von Bock and Kurt von Hammerstein - Equord formed the liaison with Major Bruno Ernst Buchrucker, who led the so - called Arbeits - Kommandos (Work Commandos), which officially was a labor group intended to assist with civilian projects, but in reality were thinly disguised soldiers that allowed Germany to exceed the limits on troop strength set by Versailles. Buchrucker′s so-called "Black Reichswehr" became infamous for its practice of murdering all those Germans whom it was suspected were working as informers for the Allied Control Commission, which was responsible for ensuring that Germany was in compliance with Part V of the Treaty of Versailles. The killings perpetrated by the "Black Reichswehr were justifed under the so-called Femegerichte (secret court) system in which alleged traitors were killed after being "convicted" in secret "trials" that the victim was unaware of. These killings were ordered by officers from Sondergruppe R as the best way to neutralize the efforts of the Allied Control Commission. Regarding the Femegerichte murders, Carl von Ossietzky wrote:

"Lieutenant Schulz (charged with the murder of informers against the "Black Reichswehr") did nothing but carry out the orders given him, and that certainly Colonel von Bock, and probably Colonel von Schleicher and General Seeckt, should be sitting in the dock beside him".

Several times Schleicher perjured himself in court when he denied that the Reichswehr had anything to do with the "Black Reichswehr" or the murders they had committed. In a secret letter sent to the President of the German Supreme Court, which was trying a member of the Black Reichswehr for murder, Seeckt admitted that the Black Reichswehr was controlled by the Reichswehr, and claimed that the murders were justified by the struggle against Versailles, so the court should acquit the defendant. Following the hyper - inflation that destroyed the German economy in 1923, between September 1923 - February 1924 the Reichswehr took over much of the administration of the country, a task that Schleicher played a prominent role in, and which left him with a taste for power. Though Seeckt disliked Schleicher, he appreciated his political finesse and came to increasingly assign Schleicher tasks dealing with politicians.

Despite Seeckt′s patronage, it was Schleicher who brought about his downfall in 1926 by leaking that Seeckt had invited the former Crown Prince to attend military manoeuvres. After Seeckt′s fall, Schleicher became, in the words of Andreas Hillgruber "in fact, if not in name", the "military - political head of the Reichswehr". Schleicher′s triumph was also the triumph of the "modern" faction within the Reichswehr who favored a total war ideology and wanted Germany to become a dicatorship that would wage total war upon the other nations of Europe.

During the 1920s, he moved up steadily in the Reichswehr, the German army, becoming the primary liaison between the Army and civilian government officials. He generally preferred to operate behind the scenes, planting stories in friendly newspapers and relying on a casual network of informers to find out what other government departments were planning. The appointment of Groener as Defence Minister in January 1928 did much to advance Schleicher′s career. Groener, who regarded Schleicher as his "adopted son", openly favored Schleicher and created the Ministeramt (Office of the Ministerial Affairs) in 1928 just for him. The new office concerned all matters relating to joint concerns of the Army and Navy, and was tasked with the liaison between the military and other departments and between the military and politicians. Groener called Schleicher "my cardinal in politics" and came to depend more and more on Schleicher to get favorable military budgets passed. Schleicher justified Groener′s confidence by getting the naval budget for 1929 passed despite the opposition of the anti - militarist Social Democrats, who formed the largest party in the Reichstag at the time. Schleicher prepared Groener′s statements to the Cabinet and attended Cabinet meetings on a regular basis. Above all, Schleicher won the right to brief President Hindenburg on both political and military matters. In late 1926 - early 1927, Schleicher told Hindenburg that if it was impossible to form a government headed by the German National People’s Party alone, then Hindenburg should "appoint a government in which he had confidence, without consulting the parties or paying attention to their wishes" and with "the order for dissolution ready to hand, give the government every constitutional opportunity to a majority in Parliament". This was the origin of the "Presidential Governments". Together with Major Oskar von Hindenburg, Otto Meißner, and General Wilhelm Groener, Schleicher was a leading member of the Kamarilla that surrounded President von Hindenburg. It was Schleicher who came up with the idea of a "Presidential Government" based on the so-called "25 / 48 / 53 formula". Under a "Presidential Government" the head of government (in this case, the chancellor), is responsible to the head of state, and not to a legislative body. The "25 / 48 / 53 formula" referred to the three articles of the Constitution that could make a "Presidential government" possible:

- Article 25 allowed the President to dissolve the Reichstag.

- Article 48 allowed the President to sign into law emergency bills without the consent of the Reichstag. However, the Reichstag could cancel any law passed by Article 48 by a simple majority within 60 days of its passage.

- Article 53 allowed the President to appoint the Chancellor.

Schleicher′s idea was to have Hindenburg use his powers under Article 53 to appoint a man of Schleicher′s choosing as chancellor, who would rule under the provisions of Article 48. Should the Reichstag threaten to annul any laws so passed, Hindenburg could counter with the threat of dissolution. Hindenburg was unenthusiastic about these plans, but was pressured into going along with them by his son along with Meißner, Groener and Schleicher. During the course of the winter of 1929 - 30, Schleicher, through various intrigues, undermined the "Grand Coalition" government of Hermann Müller with the support of Groener and Hindenburg. In March 1930, Müller′s government fell and the first "Presidential Government" headed by Heinrich Brüning came into office.

Although essentially a Prussian authoritarian in his views on order, discipline and the so-called decadence of the Weimar era, Schleicher also believed that the Army had a social function; that of an institution unifying the diverse elements in society. Interestingly, he was also opposed to policies such as Eastern Aid (Osthilfe) for the bankrupt East Elbian estates of his fellow Junkers. In economic policy, therefore, he was a relative moderate. By 1931, Germany′s restrictions of experienced military reserves were coming to an end owing to Part V of theTreaty of Versailles, which had forbade conscription. Schleicher was worried that unless Germany brought back conscription soon, then the military basis of German power would be destroyed forever. For this reason, Schleicher and the rest of the Reichswehr leadership were determined that Germany must put an end to Versailles in the near future and in the meantime saw the SA and other right wing paramilitary groups as the best substitute for conscription. With that goal in mind, Schleicher opened secret talks with the SA in 1931. Like the rest of the Reichswehr leadership, Schleicher saw democracy as an impediment to military power, and was convinced that only a dictatorship could make Germany a great military power again. Through Schleicher sometimes claimed to be a monarchist, in reality he cared nothing for the House of Hohenzollern, and often stated: "Republic or monarchy is not the question now, but rather what should the republic look like". Through Schleicher was willing to accept a republic, he was deeply hostile toward the democratic Weimar republic, and much preferred a regime dominated by the military. The German historian Eberhard Kolb wrote that:

“...from the mid 1920s onwards the Army leaders had developed and propagated new social conceptions of a militarist kind, tending towards a fusion of the military and civilian sectors and ultimately a totalitarian military state (Wehrstaat)”.

It was Schleicher′s dream to create that Wehrstaat (Military State) in which the military would reorganzie German society as part of the preparations for the total war that the Reichswehr wished to wage.

Schleicher became a major figure behind the scenes in the presidential cabinet government of Heinrich Brüning between 1930 and 1932, serving as an aide to General Groener, the Minister of Defense. Eventually, Schleicher, who established a close relationship with Reichspräsident (Reich President) Paul von Hindenburg, came into conflict with Brüning and Groener and his intrigues were largely responsible for their fall in May 1932. By coincidence, his name translated from German is "Sneaker" or "Creeper".

During the presidential election of 1932, Schleicher grew annoyed when the SPD started to proclaim themselves as allies of the government against the Nazis. On March 15, 1932 in a memo to Groener, Schleicher wrote in reference to the date of the presidential election:

"I am really looking forward to 11 April - then it will be possible to talk to this lying brood with no holds barred... After the events of the last few days, I am really glad that there is a counterweight [to the Social Democrats] in the form of the Nazis, who are not very decent chaps either and must be stomached with the greatest caution. If they did not exist, we should virtually have to invent them".

Through his secret contacts with various Nazi leaders, Schleicher planned to secure Nazi support for a new right wing "presidential government" of his creation, thereby destroying German democracy. Schleicher believed that once democracy was abolished, he could in turn destroy the Nazis by exploiting feuds between various Nazi leaders and by incorporating the SA into the Reichswehr. Reflecting Schleicher′s reputation for deviousness and being untrustworthy, Hermann Göring joked in 1932:

"Any Chancellor who has Herr von Schleicher on his side must expect sooner or later to be sunk by the Schleicher torpedo, there was a joke current in political circles - "General von Schleicher ought really to have been an Admiral for his military genius lies in shooting under water at his political friends"".

During this period, Schleicher became increasingly convinced that the solution to all of Germany′s problems was a "strong man" and that he was that "strong man". The British historian Sir John Wheeler - Bennett, who knew Schleicher well, remembered hearing Schleicher proclaim during a dinner in a posh restaurant in Berlin in the spring of 1932 that "What Germany needs today is a strong man" while tapping himself on the chest.

Schleicher told Hindenburg that his gruelling re-election campaign was the fault of Brüning who could had Hindenburg′s term extended by the Reichstag, and not done so in order to "humilate" Hindenburg by making him appear on the same stage as Social Demorcatic leaders. When in early April 1932, Brüning and Groner decided to have the SA banned following complaints from Prussia and other Lander governments, Schleicher was at first supportive, but soon changed his mind and argued against a ban. Both Schleicher and his close friend, General Kurt von Hammerstein repeatedly contended to Groener that the Reichswehr leadership did not see the banning of the SA in the best interests of the Reich.

In April 1932, when Brüning banned the SA and the SS, Groener received an angry letter from Hindenburg on April 16, 1932 demanding to know why the Reichsbanner, the para - military wing of the Social Democrats had not also been banned. This was especially the case as Hindenburg said he had solid evidence that the Reichsbanner was planning a coup. The same letter from the President was leaked and also appeared at the same day in all of the right wing German newspapers. Groener discovered the source of these allegations of a Social Democratic putsch and the leak was Eugen Ott a close protégé's of Schleicher. The British historian John Wheeler - Bennett wrote that the evidence for a SPD putsch was "flimsy" at best, and this was just Schleicher′s way of discrediting Groener in Hidndenburg′s eyes. Groener′s friends told him that there it was impossible that Ott would fabricate allegations of that sort or leak the President′s letter on his own, and that he should sack Schleicher at once. Groener, however, refused to believe that his old friend had turned on him, and refused to fire Schleicher.

At the same time, Schleicher started rumors that Groener was a secret Social Democrat and made much of the fact that his daughter was born not nine months after Groener′s marriage. On April 22, 1932, during a secret meeting, Schleicher told the SA leader — Count von Helldorf — that he together with the rest of the Reichswehr were opposed to the ban on the SA, and he would do his best to have it lifted as soon as possible. On May 8, 1932, Schleicher had a secret meeting with Hitler, during which he told him that a new "presidential government" would soon be appointed, and in exchange for promising to dissolve the Reichstag and lift the ban on the SA and the SS, received a promise from Hitler to support the new government. After Groener had been salvaged in a Reichstag debate with the Nazis over the alleged Social Democratic putsch and Groener′s lack of belief in it, Schleicher told his mentor that "he no longer enjoyed the confidence of the Army" and must resign at once. With that, Groener resigned as Defense and Interior Minister. On May 30, 1932, Schleicher′s intrigues borne fruit when Hindenburg sacked Brüning as Chancellor and appointed as his successor Franz von Papen. Schleicher had chosen von Papen, who was unknown to the German public as a new Chancellor as he believed he could control Papen from behind the scenes. Schleicher′s first choice for his "Government of the President′s Friends" had been Count Kuno von Westarp, by which means he hoped to retain Brüning — who was a close friend of Westarp — in the Cabinet. When Brüning — who was deeply hurt and angry about Schleicher′s treatment of him — made it clear that he would not serve in the new government at all, Schleicher dropped Westarp. Other possible names mentioned to head the new government were Alfred Hugenberg and Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, both of whom were vetoed by Hindenburg. Schleicher finally chose Papen because he was an old friend of Schleicher′s and because of his reputation for being superficial and his obscurity. At the time of Papen′s appointment, Schleicher boasted that "I′m not the soul of the cabinet, but I am perhaps its will". The German historian Eberhard Kolb wrote of Schleicher′s "key role" in the downfall of not only Brüning, but also the Weimar republic, for by bringing down Brüning Schleicher unintentionally and quite unnecessarily set off a series of events that led directly to the Third Reich.

Schleicher′s example in bringing down the Brüning government led to a much overt politicization of the Reichswehr. Starting the spring of 1932, a number of officers whom the British historian John Wheeler - Bennett described as "crypto - Nazis" such as Werner von Blomberg, Wilhelm Keitel and Walther von Reichenau all started talks on their own with the NSDAP. Without realizing it, Schleicher′s example served to undermine his own power since in part his power had always rested on the fact that he was the only general who was allowed to talk to the politicians.

The new Chancellor, Franz von Papen, in return hand - picked Schleicher as Minister of Defense. The first act of the new government was to dissolve the Reichstag in accodance with Schleicher′s "gentlemen′s aggreement" with Hitler on June 4, 1932. On June 15, 1932, the new government lifted the ban on the SA and the SS, who were secretly encouraged to indulge in as much violence as possible. Schleicher wanted as much mayhem on the streets as possible both to discredit democracy and to provide a pretext for the new authoritarian regime he was working to create. Besides for ordering new elections, Schleicher and Papen worked together to undermine the Social Democratic government of Prussia headed by Otto Braun. To this end, Schleicher fabricated evidence that the Prussian police under Braun's orders were favoring the Communist Rotfrontkämpferbund in street clashes with the SA, which he used to get an emergency degree from Hindenburg imposing Reich control on Prussia. To facilitate his plans for a coup against the Prussian government and to avert the danger of a general strike which had defeated the Kapp Putsch of 1920, Schleicher had a series of secret meetings with trade union leaders, during which he promised them a leading role in the new authoritarian political system he was building, in return for which he received a promise that there would be no general strike in support of Braun. In the Rape of Prussia on July 20, 1932, Schleicher had martial law proclaimed and called out the Reichswehr under Gerd von Rundstedt to oust the elected Prussian government, which was accomplished without a shot being fired. Using Article 48, Hindenburg named Papen the Reich Commissioner of Prussia. The SPD called for a general strike, but the union leaders — believing in Schleicher′s — promises ordered their members to stay at their jobs. In the Reichstag election of July 31, 1932, the NSDAP became the largest party.

In

August 1932, Hitler reneged on the "gentlemen′s aggreement" he made

with Schleicher that May, and instead of supporting the Papen government demanded the Chancellorship for himself. On

August 5, 1932, Hitler and Schleicher held a secret meeting, in which

Hitler demanded that he become Chancellor and the Ministries of the

Interior and Justice go to Nazis; Schleicher could remain as Defense

Minister. Schleicher

was willing to accept Hitler′s arrangement, and only the opposition of

Hindenburg stopped Hitler from receiving the Chancellorship in August

1932. It was at this moment that Schleicher′s influence with Hindenburg started to go into decline. Due

to Hindenburg′s opposition, Schleicher was forced to tell Hitler that

at most he could give was the Vice - Chancellorship, an offer that Hitler

refused. In September 1932, Papen′s government was defeated on a no-confidence motion in the Reichstag, at which point the Reichstag was again dissolved. In the election of November 6, 1932, the NSDAP lost seats, but still remained the largest party. By

the beginning of November, Papen who showed himself more asserative

than what Schleicher had expected, which led to a growing rift between

the two. Eventually,

Papen and Schleicher came into conflict, and when, following the

government could not maintain a working parliamentary majority, Papen

was forced to resign, and Schleicher succeeded him as Chancellor of

Germany. Schleicher brought down Papen′s government on December 3, 1932

when Papen told the Cabinet that he wished to declare martial law. Schleicher then released the results of a war game which showed that if martial law was declared then the Reichswehr would not be able to defeat the various para - military groups.

Schleicher hoped to attain a majority in the Reichstag by gaining the support of the Nazis for his government. To gain Nazi support while keeping himself Chancellor, Schleicher often talked of forming a so-called Querfront ("cross - front"), whereby he would unify Germany′s fractious special interests around a non - parliamentary, authoritarian but participatory regime as a way of forcing the Nazis to support his government. It was hoped that faced with the threat of the Querfront, Hitler would back down in his demand for the Chancellorship and support Schleicher's government instead. Schleicher was never serious about creating a querfront, which intended to be a bluff to compell the NSDAP to support the new government. As part of his attempt to blackmail Hitler into supporting his government, Schleicher went through the motions of attempting to found the Querfront by reaching out to the Social Democratic labor unions, the Christian labor unions and the left wing branch of the Nazi Party, led by Gregor Strasser. On December 4, 1932, Schleicher met with Strasser, and offered to restore the Prussian government from Reich control and make Strasser the new minister - president of Prussia. Schleicher′s hope was that the threat of a split within the Nazi Party with Strasser leading his faction out of the party would force Hitler to support the new government. At a secret meeting of the N.S.D.A.P. leaders on December 5, 1932, Strasser urged the N.S.D.A.P. to drop the demand for Hitler to become Chancellor and support Schleicher in exchange for which Schleicher would give the Nazis several cabinet portfolios. In a speech, Hitler won the Nazi leaders over to continuing his strategy, in which the Nazis would never support any government not headed by himself. Schleicher who was unaware of how Hitler had bested Strasser told his Cabinet on December 7, 1932 that he would soon have the support of the Nazi deputies in the Reichstag, which together with the Zentrum and some of the smaller parties would give his "presidential government" a majority in the Reichstag. On December 8, 1932, Strasser resigned as head of the N.S.D.A.P.′s organizational department in protest against Hitler′s strategy of opposing every government not headed by himself. At the same time, Schleicher let it be known to Hitler that he offered Strasser the Vice - Chancellorship. At another meeting of Nazi Party leaders, Hitler denounced Strasser and threatened suicide if more Nazi leaders followed Strasser. Hitler′s speech had the desired effect and Strasser was left alone in the party.

One of the main initiatives of the Schleicher government was a public works program intended to counter the effects of the Great Depression, which was sheparded by Günther Gereke whom Schleicher had appointed special commissioner for employment. The various public works projects — which were to give 2,000,000 unemployed Germans jobs by July 1933 and are often wrongly attributed to Hitler — were the work of the Schleicher government, which had passed the necessary legislation in January. The American historian Henry Ashby Turner wrote that if Schleicher had been able to stay in office for a few more months, then the economic benefits of the public works projects would had left Schleicher in a much stronger political position.

Schleicher′s relations with his Cabinet were poor. With two exceptions, Schleicher retained all of Papen′s cabinet, which meant that much of the unpopularity of the Papen government was inherited by Schleicher′s government. When one of Schleicher′s aides pointed this out, Schleicher stated: "Yes, sonny boy [Kerlchen], you're completely right; but I can't do without these people at the moment, because I have no one else". Schleicher′s secretive ways, and open contempt for his ministers made for poor relations between the Chancellor and his Cabinet. Regarding tariffs, Schleicher refused to make a firm stand. The Minister of Agriculture Magnus von Braun wanted high tariffs as a way of supporting German farmers while the Economics Minister Hermann Warmbold was opposed to further protectionism lest it damage even more the export of German industrial goods. Schleicher refused to make a decision about where he stood about tariffs, and instead told the two ministers to resolve their dispute without involving him. Braun later was to call his time in Schleicher′s government "pure torture".

Schleicher′s non - policy on tariffs hurt his government very badly when on 11 January 1933 the leaders of the Agrarian League launched a blistering attack on Schleicher in front of Hindenburg. The Agrarian League leaders attacked Schleicher for his failure to keep his promise to raise tariffs on imports of food from abroad, and his allowing to lapse a law from the Papen government that gave farmers a grace period from foreclosure if they defaulted on their debts. On the same day, the Agrarian League released a statement to the press that attacked Schleicher as "the tool of the almighty money - bag interests of internationally oriented export industry and its satellites" and accused Schleicher of "an indifference to the impoverishment of agriculture beyond the capacity of even a purely Marxist regime". Hindenburg — who always saw himself as the patron of German farmers — was most upset about what the Agrarian League leaders had told him, and summoned Schleicher at once to meet with him and the Agrarian League leaders later on the afternoon of January 11, 1933 to explain to him why Schleicher was allowing German agriculture to die. During the ensuring meeting, Hindenburg took the side of the Agrarian League and forced Schleicher to give in to the all demands of the League about bringing higher tariffs on foreign agriculture and bringing back the law extending the grace period of farmers faced with foreclosure. Despite Schleicher giving in to Hindenburg′s blowbeating, on January 12, 1933 the League released a public letter to Hindenburg asking that Schleicher be sacked at once. At the same time, Hindenburg received hundreds of letters and telegrams from Junkers who were active in the League asking for Schleicher to be dimissed as Chancellor.

Faced with intracable problems at home, Schleicher focused on foreign policy. His major interests was in winning gleichberechtigung ("equality of armaments"), that is doing away with Part V of the Treaty of Versailles, which had disarmed Germany. In a speech before a group of German journalists on January 13, 1933, Schleicher boasted about how based on the acceptance "in principle" of gleichberechtigung by the other powers at the World Disarmament Conference in December 1932 he planned to have by no later than the spring of 1934 a return to conscription and of Germany having all the weapons forbidden by Versailles. On January 15, 1933, in a speech Schleicher announced that his main foreign policy goals were gleichberechtigung and conscription.

On January 20, 1933, Schleicher missed one of his best chances to save his government. Wilhelm Frick — who was in charge of the Nazi Reichstag delegration when Hermann Göring was not present — suggested to the Reichstag′s agenda committee that the Reichstag go into recess until the next budget could be presented, which had been some time in the spring. Had this happened, by the recess end, Schleicher would have been reaping the benefits of the public works projects that his government had began in January, and in - fighting within the N.S.D.A.P. would have gotten worse. Instead, Schleicher had his Chief of Staff, Erwin Planck tell the Reichstag that the government wanted the recess to be as short as possible, which led to the recess be extended only to January 31.

The ousted Papen now had Hindenburg's ear, because the latter was beginning to have misgivings about Schleicher′s "cryptoparliamentarianism" and willingness to work with the SPD, which the old President despised. Papen was urging the aged President to appoint Hitler as Chancellor in a coalition with the Nationalist Deutschenationale Volkspartei (German National People′s Party; DNVP) who, together with Papen, would supposedly be in a position to moderate Nazi excesses. Unbeknownst to Schleicher, Papen was holding secret meetings with both Hitler and Hindenburg, who then refused Schleicher′s request for emergency powers and another dissolution of the Reichstag. On January 28, 1933, Schleicher told his Cabinet that he needed a degree from the President to dissolve the Reichstag, or otherwise his government was likely to be defeated on a no-confidence vote when the Reichstag reconvened on January 31. Schleicher then went to see Hindenburg to ask for the dissolution degree, and was refused. Upon his return to meet with the Cabinet, Schleicher announced his intention to resign, and signed the degree allowing for 500,000,000 marks to be spent on public works projects.

On January 29, Werner von Blomberg — who was part of the German delegration at the World Disarmament Conference — in Geneva was ordered to return to Berlin at once by President Hindenburg, who did so without informing Schleicher or the Army Commander, General Kurt von Hammerstein. Upon learning of this, Schleicher guessed correctly that the order to recall Blomberg to Berlin meant his government was doomed. When Blomberg arrived at the railroad station in Berlin, he was met at by Major von Kuntzen ordering him to report at once to the Defense Ministry on behalf of General von Hammerstein, and by Major Oskar von Hindenburg ordering him to report at once to the Presidential palace. Over Kuntzen's protests, Blomberg chose to go with Hindenburg to meet his father, who swore him in as Defense Minister.

That

same day, Schleicher learning that his government was about to fall,

and fearing that his rival Papen would get the Chancellorship, led

Schleicher to favor a Hitler Chancellorship. Knowing

of Papen′s by now boundless hatred for him, Schleicher knew he had no

chance of becoming Defense Minister in a new Papen government, but he

felt his chances of becoming the Defense Minister in a Hitler government

were very good. At

this time, Schleicher told Meissner "If Hitler wants to establish a

dictatorship, the Army will be a dictatorship within the dictatorship" headed by himself. Schleicher sent his close associate General Kurt von Hammerstein - Equord to meet with Hitler on January 29, during which Hammerstein warned Hitler not to trust Papen, and promised that the Reichswehr stood behind Hitler being appointed Chancellor. Through

Papen had made it clear that he would never serve in a government with

Schleicher, when Hamerstein asked if Schleicher could become Defense

Minister in a Hitler government, Hitler gave a positive answer. When Hammmerstein and Schleicher met later on the evening of January 29 to discuss what Hitler had said, they dispatched Werner von Alvensleben to meet Hitler who was having dinner at the apartment of Joseph Goebbels to seek further assurances that Schleicher could serve in a Hitler government. During his visit, Alvensleben had proclaimed very loudly that the Reichswehr would use force if any government emerged that was not to the Army′s liking. When

after Alvensleben′s return without a clear answer as to where Hitler

stood about having Schleicher as Defense Minister, Hammerstein phoned

Hitler to warn him that he was faced with a fait accompli, by which Hammerstein meant a Papen government without the Nazis. Hitler however misunderstood Hammerstein′s remark as implying that Schleicher was about to launch a putsch to keep him out of power. In

a climate of crisis with wild rumours running rampant that Schleicher

was moving troops into Berlin to depose Hindenburg, Papen convinced the

President that there was not a moment to lose, and to appoint Hitler

chancellor the next day. The President dismissed Schleicher, calling

Hitler into power on 30 January 1933. In the following months, the Nazis

issued the Reichstag Fire Decree and the Enabling Act, transforming Germany into a totalitarian dictatorship.

In the spring of 1934, hearing of the growing rift between Ernst Röhm and Hitler over the role of the SA in the Nazi state led Schleicher to start playing politics again. Schleicher criticized the current Hitler cabinet, while some of Schleicher′s followers — such as General Ferdinand von Bredow and Werner von Alvensleben — started passing along lists of a new Hitler Cabinet in which Schleicher would become Vice - Chancellor, Röhm Minister of Defense, Brüning Foreign Minister and Strasser Minister of National Economy. The British historian Sir John Wheeler - Bennett — who knew Schleicher and his circle well — wrote that the "lack of discretion" that Bredow displayed as he went about showing anyone who was interested the list of the proposed cabinet was "terrifying". Fearing this would lead to his overthrow and the collapse of his regime, Hitler had considered Schleicher a target for assassination for some time. When, on 30 June 1934, the Night of the Long Knives occurred, Schleicher was one of the chief victims. While in his house, he was gunned down; hearing the shots, his wife came into the room, whereupon she was also shot.

At his funeral, Schleicher′s good friend General Kurt von Hammerstein - Equord was much offended when the SS refused to allow him to attend the service and confiscated the wreaths that the mourners had brought. Hammerstein — together with Generalfeldmarshall August von Mackensen — launched a campaign to have Schleicher rehabilitated. In his speech to the Reichstag on July 13 justifying his actions, Hitler denounced Schleicher for conspiring with Röhm to overthrow the government, whom Hitler alleged were both traitors working in the pay of France. Since Schleicher was a good friend of André François - Poncet, and because of his reputation for intrigue, the claim that Schleicher was working for France had enough certain surface plausibility for most Germans to accept it, though it was not in fact true. The falsity of Hitler′s claims could be seen in that François - Poncet was not declared persona non grata as normally would happen if an Ambassador were caught being involved in a coup plot against his host government. In late 1934 - early 1935, Werner von Fritsch and Werner von Blomberg, whom Hammerstein had shamed into joining his campaign, successfully pressured Hitler into rehabilitating General von Schleicher, claiming that as officers they could not stand the press attacks on Schleicher, which portrayed him as a traitor working for France. In a speech given on January 3, 1935 at the Berlin State Opera, Hitler stated that Schleicher had been shot "in error", that his murder had been ordered on the basis of false information, and that Schleicher′s name was to be restored to the honor roll of his regiment. The remarks rehabiliting Schleicher were not published in the German press, though Generalfeldmarshall von Mackensen announced Schleicher′s rehabilition at a public gathering of General Staff officers on February 28, 1935. As far as the Army was concerned, the matter of Schleicher′s murder was settled. However, the Nazis continued in private to accuse Schleicher of high treason. Hermann Göring told Jan Szembek during a visit to Warsaw in January 1935 that Schleicher had urged Hitler in January 1933 to reach an understanding with France and the Soviet Union, and partition Poland with the latter, and that was why Hitler had Schleicher killed. Hitler told the Polish Ambassador Józef Lipski on May 22, 1935 that Schleicher was "rightfully murdered, if only because he had sought to maintain the Rapallo Treaty".