<Back to Index>

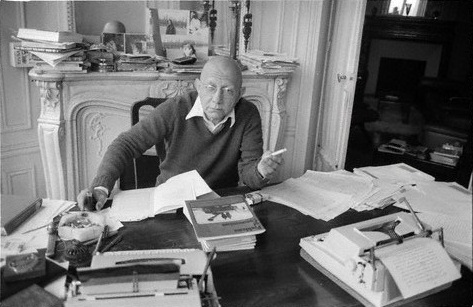

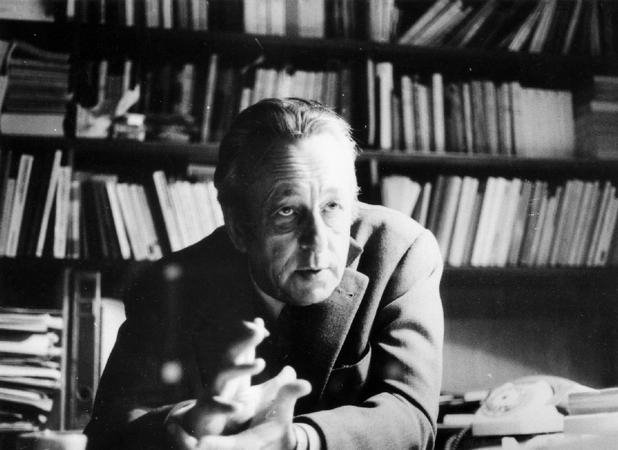

- Philosopher and Economist Cornelius Castoriadis (Κορνήλιος Καστοριάδης), 1922

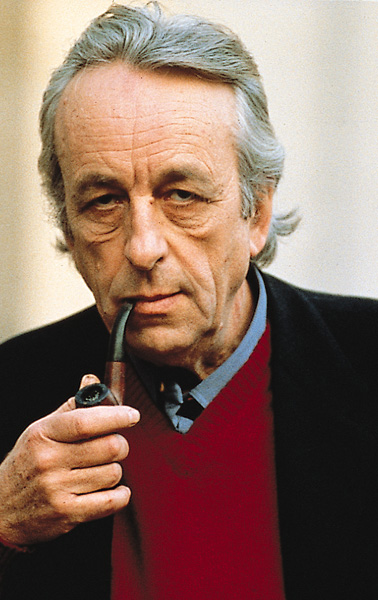

- Philosopher Louis Pierre Althusser, 1918

PAGE SPONSOR

Cornelius Castoriadis (Greek: Κορνήλιος Καστοριάδης, March 11, 1922 - December 26, 1997) was a Greek philosopher, social critic, economist, psychoanalyst, author of The Imaginary Institution of Society, and co-founder of the Socialisme ou Barbarie group.

Castoriadis was born in Constantinople and his family moved in 1922 to Athens. He developed an interest in politics after he came into contact with Marxist thought and philosophy at the age of 13. His first active involvement in politics occurred during the Metaxas Regime (1937), when he joined the Athenian Communist Youth (Kommounistiki Neolaia). In 1941 he joined the Communist Party (KKE), only to leave one year later in order to become an active Trotskyist. The latter action resulted in his persecution by both the Germans and the Communist Party. In 1944 he wrote his first essays on social science and Max Weber, which he published in a magazine named "Archive of Sociology and Ethics" (Archeion Koinoniologias kai Ithikis). During the December 1944 violent clashes between the communist led ELAS and the Papandreou government, aided by British troops, Castoriadis heavily criticized the actions of the KKE. After earning degrees in political science, economics and law from the University of Athens, he sailed to Paris, where he remained permanently, to continue his studies under a scholarship offered by the French Institute.

Once in Paris, Castoriadis joined the Trotskyist Parti Communiste Internationaliste, but broke with it by 1948. He then joined Claude Lefort and others in founding the libertarian socialist group and the journal Socialisme ou Barbarie (1949 – 1966), which included Jean - François Lyotard and Guy Debord as members for a while, and profoundly influenced the French intellectual left. Castoriadis had links with the group around C.L.R. James until 1958. Also strongly influenced by Castoriadis and Socialisme ou Barbarie were the British group and journal Solidarity and Maurice Brinton.

At the same time, he worked as an economist at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development until 1970, which was also the year when he obtained French citizenship. Consequently, his writings prior to that date were published pseudonymously, as Pierre Chaulieu, Paul Cardan, etc. Castoriadis was particularly influential in the turn of the intellectual left during the 1950s against the Soviet Union, because he argued that the Soviet Union was not a communist, but rather a bureaucratic state, which contrasted with Western powers mostly by virtue of its centralized power apparatus. His work in the OECD substantially helped his analyses. In the latter years of Socialisme ou Barbarie, Castoriadis came to reject the Marxist theories of economics and of history, especially in an essay on Modern Capitalism and Revolution (first published in Socialisme ou Barbarie, 1960 – 61; first London Solidarity English translation, 1963).

When Jacques Lacan's disputes with the International Psychoanalytical Association led to a split and the formation of the École Freudienne de Paris in 1964, Castoriadis became a member (as a non - practitioner). In 1969 Castoriadis split from the EFP with the "Quatrième groupe". He trained as a psychoanalyst and began to practice in 1974.

In his 1975 work, L'institution imaginaire de la société (Imaginary Institution of Society), and in Les carrefours du labyrinthe (Crossroads in the Labyrinth), published in 1978, Castoriadis began to develop his distinctive understanding of historical change as the emergence of irrecoverable otherness that must always be socially instituted and named in order to be recognized. Otherness emerges in part from the activity of the psyche itself. Creating external social institutions that give stable form to what Castoriadis terms the magma of social significations allows the psyche to create stable figures for the self, and to ignore the constant emergence of mental indeterminacy and alterity.

For Castoriadis, self examination, as in the ancient Greek tradition, could draw upon the resources of modern psychoanalysis. Autonomous individuals — the essence of an autonomous society — must continuously examine themselves and engage in critical reflection. He writes:

...psychoanalysis can and should make a basic contribution to a politics of autonomy. For, each person's self - understanding is a necessary condition for autonomy. One cannot have an autonomous society that would fail to turn back upon itself, that would not interrogate itself about its motives, its reasons for acting, its deep - seated [profondes] tendencies. Considered in concrete terms, however, society doesn't exist outside the individuals making it up. The self - reflective activity of an autonomous society depends essentially upon the self - reflective activity of the humans who form that society.

Castoriadis was not calling for every individual to undergo psychoanalysis, per se. Rather, by reforming education and political systems, individuals would be increasingly capable of critical self - and social reflection. He offers: "if psychoanalytic practice has a political meaning, it is solely to the extent that it tries, as far as it possibly can, to render the individual autonomous, that is to say, lucid concerning her desire and concerning reality, and responsible for her acts: holding herself accountable for what she does."

In his 1980 Facing The War text,

he took the view that Russia had become the primary world military

power. To sustain this, in the context of the visible economic

inferiority of the Soviet Union in the civilian sector, he proposed that

the society may no longer be dominated by the party - state bureaucracy

but by a "stratocracy" -

a separate and dominant military sector with expansionist designs on

the world. He further argued that this meant there was no internal class

dynamic which could lead to social revolution within Russian society

and that change could only occur through foreign intervention.

In 1980, he joined the faculty of the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales.

On December 26, 1997, he died from complications following heart surgery.

Edgar Morin proposed that Castoriadis's work will be remembered for its remarkable continuity and coherence as well as for its extraordinary breadth which was "encyclopaedic" in the original Greek sense, for it offered us a "paideia," or education, that brought full circle our cycle of otherwise compartmentalized knowledge in the arts and sciences. Castoriadis wrote essays on mathematics, physics, biology, anthropology, psychoanalysis, linguistics, society, economics, politics, philosophy, and art.

One of Castoriadis's many important contributions to social theory was the idea that social change involves radical discontinuities that cannot be understood in terms of any determinate causes or presented as a sequence of events. Change emerges through the social imaginary without determinations, but in order to be socially recognized must be instituted as revolution. Any knowledge of society and social change “can exist only by referring to, or by positing, singular entities… which figure and presentify social imaginary significations.”

Castoriadis

used traditional terms as much as possible, though consistently

redefining them. Further, some of his terminology changed throughout the

later part of his career, with the terms gaining greater consistency

but breaking from their traditional meaning (neologisms). When reading

Castoriadis, it is helpful to understand what he means by the terms he

uses, since he does not redefine the terms in every piece where he

employs them. Here are a few.

The concept of autonomy appears to be a key theme in his early postwar writings and he continued to elaborate on its meaning, applications and limits until his death, gaining him the title of "Philosopher of Autonomy". The word itself is of Greek origin, with auto meaning 'by-itself' and nomos meaning law, defining the condition of creating one's own laws, whether as an individual or a whole society. Castoriadis noticed that while all societies create their own institutions (laws, traditions and behaviors), autonomous societies are those in which their members are aware of this fact, and explicitly self - institute (αυτο - νομούνται). In contrast, the members of heteronomous societies (hetero = others) attribute their imaginaries to some extra - social authority (i.e., God, ancestors, historical necessity).

This relates to what he identified as the need of societies to legitimize their laws, or explain why their laws are good and just. Tribal societies for example did that through religion, believing that the laws where given to them by a super - natural ancestor or god and so must be true. Capitalist societies legitimize their system (capitalism) through 'reason', claiming that their system makes logical sense. Castoriadis observes that nearly all such efforts are tautological in that they legitimize a system through rules defined by the system itself. So just like the Old Testament and the Koran claim that 'There is only one God, God', capitalist societies first define what logic is: the maximization of utility and minimization of cost, and then base their system on that logic.

As he explains in one of his lectures in the Greek village of Leonidio in 1984, many newly founded societies start from an autonomous state which is usually in the form of direct democracy, like the town hall meetings during the American Independence and the local assemblies of the Paris Commune. What they end up with however is a form of governance by which, the citizens, do not legislate directly but delegate this power to a group of experts who remain in power, largely unchecked by official means, for a number of years. The ancient Greeks on the other hand developed a system of continuous autonomy where the people (demos) voted constantly on matters of government and law and where the elected rulers, the Archons, were mainly asked to enforce them. In such a system, courts of law were governed by common citizens who were appointed to the degree of judge briefly and army generals were voted in by the people and had to convince them of the correctness of their decisions. Taking some poetic license to expand this point he says that in this system, the president of the national treasury could have been a Phoenician slave, since he would only be asked to implement the rulings of the demos.

Castoriadis's

writings delve at length into the philosophy and politics of the

ancient Greeks who, as a true autonomous society knew that laws are

man made and legitimization tautological. They challenged these laws on a

constant basis and yet obeyed them to the same degree (even to the

extent of enforcing capital punishment) proving that autonomous

societies can indeed exist.

This term originates in the writings of the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan and is strongly associated with Castoriades' work. To understand it better we might think of its usual context, the "imaginary foundation of societies". By that, Castoriadis means that societies, together with their laws and legalizations, are founded upon a basic conception of the world and man's place in it. Traditional societies had elaborate imaginaries, expressed through various creation myths, by which they explained how the world came to be and how it is sustained. Capitalism did away with this mythic imaginary by replacing it with what it claims to be pure reason (as examined above). That same imaginary is, interestingly enough, the foundation of its opposing ideology, Communism. By that measure he observes, first in his main criticism of Marxism, titled the Imaginary Institution of Society, as well as speaking in Brussels, that these two systems are more closely related than was previously thought, since they share the same industrial revolution type imaginary: that of a rational society where man's welfare is materially measurable and infinitely improvable through the expansion of industries and advancements in science. In this respect Marx failed to understand that technology is not, as he claimed, the main drive of social change, since we have historical examples where societies possessing near identical technologies formed very different relations to them. An example given in the book are France and England during the industrial revolution with the second being much more liberal than the first.

Similarly, In the issue of ecology he observes that the problem facing our environment are only present within the capitalist imaginary that values the continuous expansion of industries. Trying to solve it by changing or managing these industries better might fail, since it essentially acknowledges this imaginary as real, thus perpetuating the problem.

So, imaginaries are directly responsible for all aspects of culture. The Greeks had an imaginary by which the world stems from Chaos and the ancient Jews an imaginary by which the world stems from the will of a pre-existing entity, God. The former developed therefore a system of immediate democracy where the laws where ever changing according the people's will while the second a theocratic system according to which man is in an eternal quest to understand and enforce the will of God.

This

is a concept that one encounters frequently in Castoriades work (in all

the references above for example). According to that, the Greeks

developed an imaginary by which the world is a product of Chaos, as narrated by both Homer and Hesiod. The word has since been promoted to a scientific term, but Castoriadis is inclined to believe that although the Greeks had sometimes expressed Chaos in that way (as a system too complex to be understood), they mainly referred to it as nothingness.

He then concludes what made the ancient Greeks different to other

nations is exactly that core imaginary, which essentially says, that if

the world is created out of nothing then man can indeed, in his brief

time on earth, model it as he sees fit, without trying to conform on

some preexisting order like a divine law. He contrasted that sharply to

the Biblical imaginary, which sustains all Judaic societies to this day,

according to which, in the beginning of the world there was a God, a

willing entity and man's position therefore is to understand that Will

and act accordingly.

Castoriadis views the political organization of the ancient Greek city states as a model of an autonomous society. He argues that their direct democracy was not based, as many assume, in the existence of slaves and / or the geography of Greece, which forced the creation of small city states, since many other societies had these preconditions but did not create democratic systems. Same goes for colonization since the neighboring Phoenicians, who had a similar expansion in the Mediterranean, where monarchical till their end. During this time of colonization however, around the time of Homer's Epic poems, we observe for the first time that the Greeks instead of transferring their mother city's social system to the newly established colony, they, for the first time in known history, legislate anew from the ground up. What also made the Greeks special was the fact that, following above, they kept this system as a perpetual autonomy which led to direct democracy.

This phenomenon of autonomy is again present in the emergence of the states of northern Italy during the Renaissance, again as a product of small independent merchants.

He sees a tension in the modern West between, on the one hand, the potentials for autonomy and creativity and the proliferation of "open societies" and, on the other hand, the spirit - crushing force of capitalism. These are characterized as the capitalist imaginary and the creative imaginary:

I think that we are at a crossing in the roads of history, history in the grand sense. One road already appears clearly laid out, at least in its general orientation. That's the road of the loss of meaning, of the repetition of empty forms, of conformism, apathy, irresponsibility, and cynicism at the same time as it is that of the tightening grip of the capitalist imaginary of unlimited expansion of "rational mastery," pseudorational pseudomastery, of an unlimited expansion of consumption for the sake of consumption, that is to say, for nothing, and of a technoscience that has become autonomized along its path and that is evidently involved in the domination of this capitalist imaginary. The other road should be opened: it is not at all laid out. It can be opened only through a social and political awakening, a resurgence of the project of individual and collective autonomy, that is to say, of the will to freedom. This would require an awakening of the imagination and of the creative imaginary.

He argues that, in the last two centuries, ideas about autonomy again come to the fore: "This extraordinary profusion reaches a sort of pinnacle during the two centuries stretching between 1750 and 1950. This is a very specific period because of the very great density of cultural creation but also because of its very strong subversiveness."

Castoriadis

has influenced European (especially continental) thought in important

ways. His interventions in sociological and political theory have resulted in some of the best known writing to emerge from the

continent (especially in the figure of Jürgen Habermas, who often can be seen to be writing against Castoriadis). Sociologist Hans Joas attempted

in the early 1980s to bring Castoriadis' work and thought to an

anglophone audience, as did others, with little success. However, the publication in 2009 of Australian Jeff Klooger's Castoriadis: Psyche, Society, Autonomy by

the academic publisher Brill marks a significant advance in the area of

English language studies of Castoriadis's main ideas. In the last two

decades there has been a growing interest in Castoriadis' work centred

in Australia, stemming from Castoriadis' association with the

Melbourne based journal Thesis Eleven (which is named for the eleventh and final of Karl Marx's Theses on Feuerbach,

which simply states "Philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the

world in various ways; the point is to change it.") The journal

published many of his essays in English translation for the first time. A

number of books on Castoriadis by Australian scholars are forthcoming,

the first of these being the work by Jeff Klooger mentioned above, to

date the only book length study of Castoriadis to have appeared in

English.

Louis Pierre Althusser (16 October 1918 – 22 October 1990) was a French Marxist philosopher. He was born in Algeria and studied at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, where he eventually became Professor of Philosophy.

Althusser was a longtime member - although sometimes a strong critic - of the French Communist Party. His arguments and theses were set against the threats that he saw attacking the theoretical foundations of Marxism. These included both the influence of empiricism on Marxist theory, and humanist and reformist socialist orientations which manifested as divisions in the European communist parties, as well as the problem of the "cult of personality" and of ideology itself.

Althusser is commonly referred to as a Structural Marxist, although his relationship to other schools of French structuralism is not a simple affiliation and he was critical of many aspects of structuralism.

Althusser's life was marked by periods of intense mental illness. During one of his bouts, he killed his wife by strangling her.

Althusser wrote two autobiographies, L'Avenir dure longtemps (The Future Lasts a Long Time) which is published in The United States as "The Future Lasts Forever," in a single volume with Althusser's other, shorter, earlier autobiography, "The Facts." They are not straightforward autobiographies and cannot be treated as such (at least without provisions) for purposes of strict biographical information.

Althusser was born in French Algeria in the town of Birmendreïs, near Algiers, to a pieds - noirs family. He was named after his paternal uncle who had been killed in the First World War. Althusser alleged that his mother had intended to marry his uncle and married his father only because of the brother's demise. Althusser also alleges that his mother treated him as a substitute for his deceased uncle, to which he attributed deep psychological damage.

Following the death of his father, Althusser moved from Algiers with his mother and younger sister to Marseilles, where he spent the rest of his childhood. He joined the Roman Catholic youth movement Jeunesse Etudiante Chrétienne in 1937. Althusser performed brilliantly at school at the Lycée du Parc in Lyon and was accepted to the elite École normale supérieure (ENS) in Paris. However, he found himself enlisted in the run - up to World War II, and like most French soldiers following the Fall of France Althusser was interned in a German POW camp. Here, his move towards Communism was to begin. He remained in the camp for the rest of the war, and this experience further contributed to his lifelong bouts of mental instability.

After the war, Althusser was able finally to attend ENS. However, he was in poor health, both mentally and physically. In 1947 he received electroconvulsive therapy.

Althusser was from this time to suffer from periodic mental illness for

the rest of his life. The ENS was sympathetic, however, allowing him to

reside in his own room in the school infirmary. Althusser found himself

living at the ENS in the Rue d'Ulm for decades, except for periods of

hospitalization.

In 1946, Althusser met Hélène Rytman, a revolutionary of Lithuanian - Jewish origin and eight years his senior. She remained his companion, and eventually his wife, until her death, at his hands, in 1980.

Formerly a devout if left wing Catholic, Althusser joined the French Communist Party (PCF) in 1948, a time when others such as Merleau - Ponty were losing sympathy for the party. That same year, Althusser passed the agrégation in philosophy with a dissertation on Hegel, which allowed him to become a tutor at the ENS.

With the Twentieth Party Congress in 1956, Nikita Khrushchev began the process of "de-Stalinisation". For many Marxists - including the PCF's leading theoretician Roger Garaudy and the pre-eminent existentialist Jean - Paul Sartre - this meant the recovery of the humanist roots of Marx's thought, and the opening of a dialogue between Marxists and moderate socialists, existentialists and Christians. Althusser, however, opposed this trend, proffering a "theoretical anti - humanism" and sympathizing with the criticisms made by the Communist Party of China, albeit cautiously and careful not to identify himself with Maoism. His stance during this period earned him notoriety within the PCF and he was attacked by its secretary general Waldeck Rochet. As a philosopher, he was treading another path, which would later lead him to "aleatory materialism"; however, this did not stop him from defending Marxist orthodox thought in relation to his own position and work, such as during his 1973 reply to John Lewis.

Despite the involvement of many of his students in the events of May 1968, Althusser initially greeted these developments with silence. He was later to parallel the official PCF line in describing the students as victim to "infantile" leftism. As a result, Althusser was attacked by many former supporters. In response to these criticisms, he revised some of his positions, claiming that his earlier writings contained mistakes, and a significant shift in emphasis was seen in his later works.

On 16 November 1980, Althusser strangled his wife Hélène to death, following a period of mental instability. There

were no witnesses, and the exact circumstances are debated with some

claiming it was deliberate, others accidental. Althusser himself claimed

not to have a clear memory of the event, saying that, while he was

massaging his wife's neck, he discovered he had strangled her. Althusser

was diagnosed as suffering from diminished responsibility,

and he was not tried, but instead committed to the Sainte - Anne

psychiatric hospital. Althusser remained in hospital until 1983. Upon

release, he moved to Northern Paris and lived reclusively, seeing few

people. He continued to work and write, but published little. A notable

exception is his autobiography, L'Avenir dure longtemps, in which Althusser describes the killing (among other topics). He died of a heart attack on 22 October 1990 at the age of 72. Much of his post 1980 work has been published posthumously.

Althusser's earlier works include the influential volume Reading Capital, which collects the work of Althusser and his students on an intensive philosophical re-reading of Karl Marx's Capital. The book reflects on the philosophical status of Marxist theory as "critique of political economy," and on its object. The current English edition of this work includes only the essays of Althusser and Étienne Balibar, while the original French edition contains additional contributions from Jacques Ranciere, Pierre Macherey, and Roger Establet.

Several of Althusser's theoretical positions have remained very influential in Marxist philosophy. The introduction to his collection For Marx proposes a great "epistemological break" between Marx's early writings (1840 – 45) and his later, properly Marxist texts, borrowing a term from the philosopher of science Gaston Bachelard. His essay Marxism and Humanism is a strong statement of anti - humanism in Marxist theory, condemning ideas like "human potential" and "species - being", which are often put forth by Marxists, as outgrowths of a bourgeois ideology of "humanity". His essay Contradiction and Overdetermination borrows the concept of overdetermination from psychoanalysis, in order to replace the idea of "contradiction" with a more complex model of multiple causality in political situations (an idea closely related to Antonio Gramsci's concept of hegemony).

Althusser is also widely known as a theorist of ideology. His best known essay, Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses: Notes Toward an Investigation, establishes the concept of ideology. Althusser's theory of ideology draws on Marx and Gramsci, but also on Freud's and Lacan's concepts of the unconscious and mirror - phase respectively, and describes the structures and systems that enable the concept of the self. These structures, for Althusser, are both agents of repression and inevitable - it is impossible to escape ideology, to not be subjected to it.

Althusser's

thought went through an evolution in his lifetime, and has been the

subject of argument and debate, especially within Marxism and specifically concerning his theory of knowledge (epistemology).

Althusser's contention is that Marx's thought has been fundamentally misunderstood and underestimated. He fiercely condemns various interpretations of Marx's works - historicism, idealism, economism - on the grounds that they fail to realize that with the "science of history", historical materialism, Marx has constructed a revolutionary view of social change. These errors, he believes, result from the notion that Marx's entire body of work can be understood as a coherent whole. Rather, Althusser holds, Marx's thought contains a radical "epistemological break". Though the works of the young Marx are bound by the categories of German philosophy and classical political economy, with The German Ideology (written in 1845) there is a sudden and unprecedented departure. This "break" represents a shift in Marx's work to a fundamentally different "problematic", i.e., a different set of central propositions and questions posed, a different theoretical framework. The problem (according to Althusser) is compounded by the fact that even Marx himself does not fully comprehend the significance of his own work, being only able to communicate it obliquely and tentatively. The shift can only be revealed by way of a careful and sensitive "symptomatic reading". Thus, Althusser's project is to help us fully grasp the originality and power of Marx's extraordinary theory, giving as much attention to what is not said as to the explicit. Althusser holds that Marx has discovered a "continent of knowledge", History, analogous to the contributions of Thales to mathematics, Galileo to physics or, better, Freud's psychoanalysis, in that the structure of his theory is unlike anything posited by his predecessors.

Althusser believes that Marx's work is fundamentally incompatible with its antecedents because it is built on a ground - breaking epistemology that rejects the distinction between subject and object. In opposition to empiricism, Althusser claims that Marx's philosophy, dialectical materialism, counters the theory of knowledge as vision with a theory of knowledge as production. On the empiricist view, a knowing subject encounters a real object and uncovers its essence by means of abstraction. On the assumption that thought has a direct engagement with reality, or an unmediated vision of a 'real' object, the empiricist believes that the truth of knowledge lies in the correspondence of a subject's thought to an object that is external to thought itself. By contrast, Althusser claims to find latent in Marx's work a view of knowledge as "theoretical practice". For Althusser, theoretical practice takes place entirely within the realm of thought, working upon theoretical objects and never coming into direct contact with the real object that it aims to know. Knowledge is not discovered, but rather produced by way of three "Generalities": I, the "raw material" of pre - scientific ideas, abstractions and facts; II, a conceptual framework (or "problematic") brought to bear upon these; III, the finished product of a transformed theoretical entity, concrete knowledge. On this view, the validity of knowledge is not guaranteed by its correspondence to something external to itself; because Marx's historical materialism is a science, it contains its own internal methods of proof. It is therefore not governed by interests of society, class, ideology or politics, and is distinct from the economic superstructure.

In addition to its unique epistemology, Marx's theory is built on concepts - such as forces and relations of production - that have no counterpart in classical political economy. Even when existing terms are adopted - for example, the theory of surplus value that combines David Ricardo's concepts of rent, profit and interest - their meaning and relation to other concepts in the theory is significantly different. However, more fundamental to Marx's "break" is a rejection of homo economicus, or the idea, held by the classical economists, that the needs of individuals can be treated as a fact or "given" independent of any economic organization. For the classical economists, such individual needs can serve as a premise for a theory explaining the character of a mode of production and as an independent starting point for a theory about society. Where political economy explains economic systems as a response to individual needs, Marx's analysis accounts for a wider range of social phenomena in terms of the parts they play in a structured whole. Consequently, Marx's Capital has greater explanatory power than political economy, in that it provides both a model of the economy and a description of the structure and development of a whole society. In Althusser's view, Marx does not simply argue that human needs are largely created by their social environment and thus vary with time and place; rather, he abandons the very idea that there can be a theory about what people are like that is prior to any theory about how they come to be that way.

Though Althusser steadfastly holds onto the claim of its existence, he

later asserts that the turning point's occurrence around 1845 is not so

clearly defined, as traces of humanism, historicism and Hegelianism are to be found in Capital. He even goes so far as to state that only Marx's Critique of the Gotha Programme and some marginal notes on a book by Adolph Wagner are fully free from humanist ideology. In

line with this, Althusser replaces his earlier definition of Marx's

philosophy as the "theory of theoretical practice" with a new belief in

"politics in the field of history" and "class struggle in theory". Althusser considers the epistemological break to be a process instead of a clearly defined event, the product of incessant struggle against ideology. The distinction

between ideology and science or philosophy is thus not assured once and

for all by the epistemological break.

Because of Marx's belief that the individual is a product of society, it is, in Althusser’s view, pointless to try to build a social theory on a prior conception of the individual. The subject of observation is not individual human elements, but rather "structure". As he sees it, Marx does not explain society by appealing to the properties of individual persons - their beliefs, desires, preferences and judgements - but rather defines society as a set of fixed "levels" and "practices". He uses this analysis to defend Marx’s historical materialism against the charge that it crudely posits a base (economic level) and superstructure (culture / politics) 'rising upon it' and then attempts to explain all aspects of the superstructure by appealing to features of the (economic) base (the well known architectural metaphor). For Althusser, it is a mistake to attribute this economic determinist view to Marx: much as he criticizes the idea that a social theory can be founded on an historical conception of human needs, so does he critique the idea that economic practice can be used in isolation to explain other aspects of society. Althusser believes that both the base and the superstructure are interdependent, although he keeps to the classic Marxist materialist understanding of the determination of the base 'in the last instance' (albeit with some extension and revision). The advantage of levels and practices over individuals as a starting point is that although each practice is only a part of a complex whole of society, a practice is a whole in itself in that it consists of a number of different kinds of parts; economic practice, for example, contains raw materials, tools, individual persons, etc. all united in a process of production.

Althusser conceives of society as an interconnected collection of these wholes – economic practice, ideological practice and politico - legal practice. Although each practice has a degree of relative autonomy, together they

make up one complex structured whole (social formation). In his view all levels and practices are dependent on each other. For example, amongst the relations of production of capitalist societies are the buying and selling of labor power by capitalists and workers.

These relations are part of economic practice, but can only exist

within the context of a legal system which establishes individual agents

as buyers and sellers; furthermore, the arrangement must be maintained

by political and ideological means. From this it can be seen that aspects of economic practice depend on the superstructure and vice versa. For him this was the moment of reproduction and constituted the important role of the superstructure.

An analysis understood in terms of interdependent levels and practices helps us to conceive of how society is organized, but also allows us to comprehend social change and thus provides a theory of history. Althusser explains the reproduction of the relations of production by reference to aspects of ideological and political practice; conversely, the emergence of new production relations can be explained by the failure of these mechanisms. Marx’s theory seems to posit a system in which an imbalance in two parts could lead to compensatory adjustments at other levels, or sometimes to a major reorganization of the whole. To develop this idea Althusser relies on the concepts of contradiction and non - contradiction, which he claims are illuminated by their relation to a complex structured whole. Practices are contradictory when they "grate" on one another and non - contradictory when they support one another. Althusser elaborates on these concepts by reference to Lenin’s analysis of the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Lenin posited that in spite of widespread discontent throughout Europe in the early 20th century, Russia was the country in which revolution occurred because it contained all the contradictions possible within a single state at the time. It was, in his words, the "weakest link in a chain of imperialist states". He explained the revolution in relation to two groups of circumstances: firstly, the existence within Russia of large scale exploitation in cities, mining districts, etc., disparity between urban industrialization and medieval conditions in the countryside, and lack of unity amongst the ruling class; secondly, a foreign policy which played into the hands of revolutionaries, such as the elites who had been exiled by the Tsar and had become sophisticated socialists.

For Althusser, this example reinforces his claim that Marx's explanation of social change is more complex than to see it as the result of a single contradiction between the forces and the relations of production. The differences between events in Russia and Western Europe highlight that a contradiction between forces and relations of production may be necessary, but not sufficient, to bring about revolution. The circumstances that produced revolution in Russia, mentioned above, were heterogeneous, and cannot be seen to be aspects of one large contradiction. Each was a contradiction within a particular social totality, at a different structural level of social practice. From this, Althusser draws the conclusion that Marx’s concept of contradiction is inseparable from the concept of a complex structured social whole. In order to emphasize that changes in social structure relate to numerous contradictions, Althusser describes these changes as "overdetermined", using a term taken from Sigmund Freud. This interpretation allows us to account for how many different circumstances may play a part in the course of events, and furthermore permits us to grasp how these circumstances may combine to produce unexpected social changes, or "ruptures".

However, Althusser does not mean to say that the events that determine social changes all have the same causal status. While a part of a complex whole, economic practice is, in his view, a "structure in dominance": it plays a major part in determining the relations between other spheres, and has more effect on them than they have on it. The most prominent aspect of society (the religious aspect in feudal formations and the economic aspect in capitalist ones) is called the "dominant instance", and is in turn determined "in the last instance" by the economy. For Althusser, the economic practice of a society determines which other aspect of that society dominates the society as a whole.

Althusser's

arguably more complex and materialist (than other Marxisms)

understanding of contradiction in terms of the dialectic attempts to rid

Marxism of the influence / vestiges of Hegelian (idealist) dialectics,

and is a component part of his general anti - humanist position.

Because Althusser held that a person's desires, choices, intentions, preferences, judgements and so forth are the products of social practices, he believed it necessary to conceive of how society makes the individual in its own image. Within capitalist societies, the human individual is generally regarded as a subject endowed with the property of being a self - conscious 'responsible' agent, whose actions can be explained by his or her beliefs and thoughts. For Althusser, however, a person’s capacity for perceiving him/her - self in this way is not innate or "given". Rather, it is acquired within the structure of established social practices, which impose on individuals the role (forme) of a subject. Social practices both determine the characteristics of the individual and give him/her an idea of the range of properties he/she can have, and of the limits of each individual. Althusser argues that many of our roles and activities are given to us by social practice: for example, the production of steelworkers is a part of economic practice, while the production of lawyers is part of politico - legal practice. However, other characteristics of individuals, such as their beliefs about the good life or their metaphysical reflections on the nature of the self, do not easily fit into these categories.

In Althusser’s view, our values, desires and preferences are inculcated in us by ideological practice, the sphere which has the defining property of constituting individuals as subjects. Ideological practice consists of an assortment of institutions called Ideological State Apparatuses (ISAs), which include the family, the media, religious organizations and, most importantly in capitalist societies, the education system, as well as the received ideas that they propagate. There is, however, no single ISA that produces in us the belief that we are self - conscious agents. Instead, we derive this belief in the course of learning what it is to be a daughter, a schoolchild, black, a steelworker, a councilor, and so forth.

Despite its many institutional forms, the function and structure of ideology is unchanging and present throughout history; as Althusser states, "ideology has no history". All ideologies constitute a subject, even though he or she may differ according to each particular ideology. Memorably, Althusser illustrates this with the concept of "hailing" or "interpellation," which draws heavily from Lacan and his concept of the Mirror Stage. He compares ideology to a policeman shouting "Hey you there!" toward a person walking on the street. Upon hearing this call, the person responds by turning around and in doing so, is transformed into a subject. The person is conscious of themselves being a subject and aware of the other person. Thus, for Althusser, being aware of other people is a form of ideology. Within that, Althusser sees subjectivity as a type of ideology. The person being hailed recognizes him/her - self as the subject of the hail, and knows to respond. Althusser calls this recognition a "mis - recognition" (méconnaissance) because it is working retroactively: a material individual is always - already an ideological subject, even before he is born. The "transformation" of an individual into a subject has always - already happened; Althusser acknowledges here a debt to Spinoza's theory of immanence. To highlight this, Althusser offers the example of Christian religious ideology, embodied in the Voice of God, instructing a person on what his place in the world is and what he must do to be reconciled with Christ. From this, Althusser draws the point that in order for that person to identify himself as a Christian, he must first already be a subject; that is to say, by responding to God's call, by following His rules, he is affirming himself as a free agent, the author of the acts for which he assumes responsibility. We can’t recognize ourselves outside of ideology, and, in fact, our very actions reach out to this overarching structure. For Althusser, we acquire our identities by seeing ourselves mirrored in ideologies.

Further to the above, Althusser advances two theses on ideology: I, "Ideology represents the imaginary relationship of individuals to their real conditions of existence"; II, "Ideology has a material existence". The first thesis tenders the familiar Marxist contention that ideologies have the function of masking the exploitative arrangements on which class societies are based.

The second thesis posits that ideology does not exist in the form of "ideas" or conscious "representations" in the "minds" of individuals. Rather, ideology consists of the actions and behaviors of bodies governed by their disposition within material apparatuses. Central to the view of individuals as responsible subjects is the notion of an explanatory link between belief and action, that

| “ | every 'subject' endowed with a 'consciousness' and believing in the 'ideas' that his 'consciousness' inspires in him and freely accepts, must act according to his ideas", must therefore inscribe his own ideas as a free subject in the actions of his material practice. | ” |

For Althusser, this is yet another effect of social practice:

| “ | I shall therefore say that, where only a single subject (such and such individual) is concerned, the existence of the ideas of his belief is material in that his ideas are his material actions inserted into his material practices governed by material rituals which are themselves defined by the material ideological apparatus from which we derive the ideas of that subject... Ideas have disappeared as such (insofar as they are endowed with an ideal or spiritual existence), to the precise extent that it has emerged that their existence is inscribed in the actions of practices governed by rituals defined in the last instance by an ideological apparatus. It therefore appears that the subject acts insofar as he is acted by the following system (set out in the order of its real determination): ideology existing in a material ideological apparatus, describing material practices governed by a material ritual, which practices exist in the material actions of a subject acting in all consciousness according to his belief. | ” |

These material rituals may be compared with Bourdieu's concept of habitus. ISAs may also anticipate Foucault's disciplinary institutions which provide a critical rethinking of Althusser.

Althusser also recognized the role played by what he termed "Repressive State Apparatus". According to Althusser, the basic function of the Repressive State Apparatus (Heads of State, government, police, courts, army etc.) is to intervene and act in favor of the ruling class by repressing the ruled class through violent and coercive means. The Repressive state apparatus (RSA) is controlled by the ruling class, because more often than not, the ruling class possesses State power. He accentuates the differences between the RSA and the ISAs as follows:

- 1. The RSA functions as a unified entity (an organized whole) as opposed to the ISA which is diverse and plural. However, what unites the disparate ISAs is the fact that they are ultimately controlled by the ruling ideology.

- 2. The RSA functions predominantly by means of repression and violence and secondarily by ideology whereas the ISA functions predominantly by ideology and secondarily by repression and violence. The ISAs function in a concealed and a symbolic manner.

At times when individuals and groups pose a threat to the dominant order the state invokes Repressive State Apparatus. The most benign measures taken by the RSA are the systems of law and courts where putatively public contractual language is invoked in order to govern individual and collective behavior. As threats to the dominant order mount, the state turns to increasingly physical and severe measures: incarceration, police force and ultimately military intervention are used in response.

Perry Anderson in his essay "Considerations on Western Marxism" writes that

"despite the huge popularity gained by the concept in many circles, ISA as a concept was never theorized by Althusser himself in any serious manner. It was merely conceived as a conjunctural and temporary tool to challenge the contemporary liberalism within the French Communist Party. A further elaboration of the concept in the hands of Nicos Paulantzas was easily demolished by Ralph Miliband in the exchanges over the pages of New Left Review. For, if all the institutions of civil society are conceptualized as part of the state, then a mere electoral victory of a left wing student organization in a University can also be said to be a victory over a part of the state!"

Although Althusser's theories were born of an attempt to defend what some saw as Communist orthodoxy, the eclecticism of his influences - drawing equally from contemporary structuralism, philosophy of science and psychoanalysis as from thinkers in the Marxist tradition - reflected a move away from the intellectual isolation of the Stalin era. Furthermore his thought was symptomatic both of Marxism's growing academic respectability and of a push towards emphasizing Marx's legacy as a philosopher rather than only as an economist or sociologist. Tony Judt saw this as a criticism of Althusser's work, saying he removed Marxism altogether from the realm of history, politics and experience, and thereby... render[ed] it invulnerable to any criticism of the empirical sort.

Althusser has had broad influence in the areas of Marxist philosophy and post - structuralism: Interpellation has been popularized and adapted by the feminist philosopher and critic Judith Butler; the concept of Ideological State Apparatuses has been of interest to Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek; the attempt to view history as a process without a subject garnered sympathy from Jacques Derrida; historical materialism was defended as a coherent doctrine from the standpoint of analytic philosophy by G.A. Cohen; the interest in structure and agency sparked by Althusser was to play a role in Anthony Giddens's theory of structuration; Althusser was vehemently attacked by British historian E.P. Thompson in his book The Poverty of Theory.

Althusser's influence is also seen in the work of economists Richard D. Wolff and Stephen Resnick, who have interpreted that Marx's mature works hold a conception of class different from the ones normally understood. For them, in Marx class does not refer to a group of people (for example, those that own the means of production versus those that do not), but to a process involving the production, appropriation and distribution of surplus labor. Their emphasis on class as a process is consistent with their reading and use of Althusser's concept of overdetermination in terms of understanding agents and objects as the site of multiple determinations.

Althusser's work has also been criticized from a number of angles. In a 1971 paper for Socialist Register, Polish philosopher Leszek Kolakowski undertook a detailed critique of structural Marxism, arguing that the concept was seriously flawed on three main points:

- I will argue that the whole of Althusser's theory is made up of the following elements: 1. common sense banalities expressed with the help of unnecessarily complicated neologisms; 2. traditional Marxist concepts that are vague and ambiguous in Marx himself (or in Engels) and which remain, after Althusser's explanation, exactly as vague and ambiguous as they were before; 3. some striking historical inexactitudes.

Kolakowski further argued that, despite Althusser's claims of scientific rigor, structural Marxism was unfalsifiable and thus unscientific, and was best understood as a quasi - religious ideology. In 1980, sociologist Axel van der Berg described

Kolakowski's critique as "devastating," proving that "Althusser retains

the orthodox radical rhetoric by simply severing all connections with

verifiable facts."

Since his death, the reassessment of Althusser's work and influence has been ongoing. The first wave of retrospective critiques and interventions ("drawing up a balance sheet") began outside of Althusser's own country France because, as Etienne Balibar pointed out in 1988, "there is an absolute taboo now suppressing the name of this man and the meaning of his writings." Balibar's remarks were made at the "Althusserian Legacy" Conference organized at SUNY Stony Brook by Michael Sprinker. The proceedings of this conference were published in September 1992 as the Althusserian Legacy and included contributions from Balibar, Alex Callinicos, Michele Barrett, Alain Lipietz, Warren Montag and Gregory Elliott among others. It also included an obituary and an extensive interview with Jacques Derrida.

Eventually, a colloquium was organized in France at the University de Paris 8 by Sylvain Lazarus on May 27, 1992. The general title was Politique et philosophie dans l'oeuvre de Louis Althusser, the proceedings of which were published in 1993.

In retrospect, Althusser's continuing importance and influence can be seen through his students. A dramatic example of this points to the editors and contibutors of the 1960s journal Cahiers pour l'Analyse:

| “ | In many ways, the "Cahiers" can be read as the critical development of Althusser's own intellectual itinerary when it was at its most robust. | ” |

This influence continues to guide some of today's most significant and provocative philosophical work, as many of these same students became eminent intellectuals in the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and 1990s: Alain Badiou, Étienne Balibar and Jacques Ranciere in philosophy, Pierre Macherey in literary criticism and Nicos Poulantzas in sociology. The prominent Guevarist Régis Debray also studied under Althusser, as did the aforementioned Derrida (with whom he at one time shared an office at the ENS), noted philosopher Michel Foucault, and the pre-eminent Lacanian psychoanalyst Jacques - Alain Miller.

Badiou has lectured and spoken on Althusser on several occasions in France, Brazil and Austria since Althusser's death. Badiou has written many studies including "Althusser: Subjectivity without a Subject" published in his book Metapolitics in 2005. Most recently, Althusser's work has been given prominence again through the interventions of Warren Montag and his circle.

As late as 2011 Althusser continued to spark controversy and debate with the publication in August of that year of Jacques Ranciere's first book Althusser's Lesson (1974). It marked the first time this groundbreaking work was to appear in its entirety in an English translation.