<Back to Index>

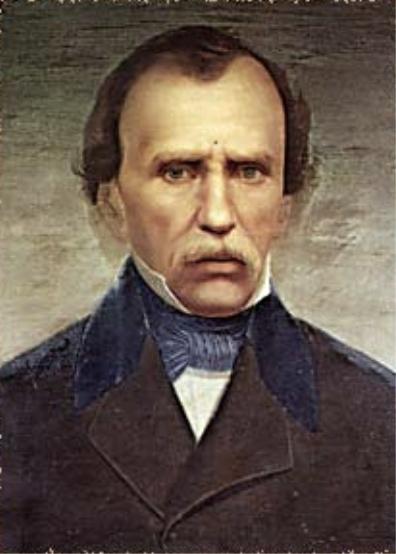

- King of Greece Otto (Όθων), 1815

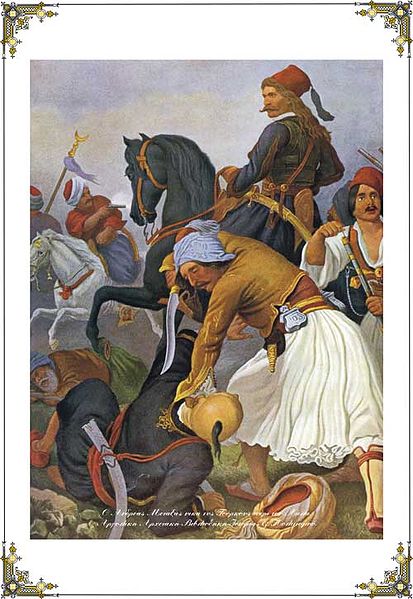

- Prime Minister of Greece Andreas Metaxas (Ανδρέας Μεταξάς), 1790

PAGE SPONSOR

Otto, Prince of Bavaria, then Othon, King of Greece (Greek: Ὄθων, Βασιλεὺς τῆς Ἑλλάδος; 1 June 1815 – 26 July 1867) was made the first modern King of Greece in 1832 under the Convention of London, whereby Greece became a new independent kingdom under the protection of the Great Powers (the United Kingdom, France and the Russian Empire).

The second son of the philhellene King Ludwig I of Bavaria, Otto ascended the newly created throne of Greece while still a minor. His government was initially run by a three man regency council made up of Bavarian court officials. Upon reaching his majority, Otto removed the regents when they proved unpopular with the people and he ruled as an absolute monarch. Eventually his subjects’ demands for a Constitution proved overwhelming and in the face of an armed but peaceful insurrection, Otto granted a Constitution in 1843.

Throughout

his reign, Otto faced political challenges concerning Greece's

financial weakness and the role of the government in the affairs of the

Church. The politics of Greece of this era was based on affiliations

with the three Great Powers, and Otto’s ability to maintain the support

of the powers was key to his remaining in power. To remain strong, Otto

had to play the interests of each of the Great Powers’ Greek adherents

against the others, while not aggravating the Great Powers. When Greece

was blockaded by the (British) Royal Navy in 1850 and again in 1853, to stop Greece from attacking the Ottoman Empire during the Crimean War,

Otto’s standing amongst Greeks suffered. As a result, there was an

assassination attempt on the Queen and finally, in 1862, Otto was

deposed while in the countryside. He died in exile in Bavaria in 1867.

He was born Prince Otto Friedrich Ludwig of Bavaria at Schloss Mirabell in Salzburg (when it belonged for a short time to the Kingdom of Bavaria), as second son of King Ludwig I of Bavaria and Therese of Saxe - Hildburghausen. Through his ancestor, the Bavarian Duke John II, Otto was a descendant of the Greek imperial dynasties of Komnenos and Laskaris.

When

he was elected king, the Great Powers extracted a pledge from Otto’s

father to restrain him from hostile actions against the Ottoman Empire, and insisted on his title being that of “King of Greece” instead of

“King of the Greeks”, which would imply a claim over the millions of

Greeks then still under Turkish rule. Not quite 18, the young prince

arrived in Greece with 3,500 Bavarian troops and three Bavarian advisors

aboard the British frigate HMS Madagascar.

He immediately endeared himself to his adopted country by adopting the

Greek national costume and Hellenizing his name to "Othon." For this

reason, some English sources call him "Otho." ("Othon" is also the

French, Spanish and Portuguese version of the German name "Otto").

Otto's reign is usually divided into 3 periods:

- a. The years of Regency: 1832 - 1835

- b. The years of Absolute Monarchy: 1835 - 1843

- c. The years of Constitutional Monarchy: 1843 - 1862

The Bavarian advisors were arrayed in a Regency Council headed by Count Josef Ludwig von Armansperg, who in Bavaria as minister of finance, had recently succeeded in restoring Bavarian credit

at the cost of his popularity. Von Armansperg was the President of the

Privy Council and the 1st representative (or Prime Minister) of the new

Greek government. The other members of the Regency Council were Karl von Abel and Georg Ludwig von Maurer with

whom von Armansperg clashed often. After the King reached his majority

in 1835, von Armansperg was made Arch - Secretary but was called

Arch - Chancellor by the Greek press.

The UK and the Rothschild bank, who were underwriting the Greek loans, insisted on financial stringency from Armansperg. The Greeks were soon more heavily taxed than under Turkish rule; as the people saw it, they had exchanged a hated Ottoman tyranny, which they understood, for government by a foreign bureaucracy, the "Bavarocracy" (Βαυαροκρατία), which they despised. (Ottoman rule had been called in Greek Tourkokratia - Τουρκοκρατία, "Turkish rule").

In addition, the regency showed little respect for local customs. Also, as a Roman Catholic, Otto himself was viewed as a heretic by many pious Greeks, however, his heirs would have to be Orthodox according to the terms of the 1843 Constitution.

Popular heroes and leaders of the Greek Revolution, like the Generals Theodoros Kolokotronis and Yiannis Makriyiannis, who opposed the Bavarian dominated regency, were charged with treason, put in jail and sentenced to death. However, they were pardoned later, under popular pressure, while the Greek judges, who resisted the Bavarian pressure and refused to sign the death penalties (like Anastasios Polyzoidis and Georgios Tertsetis), were saluted as heroes.

King

Otto’s early reign was notable for one more reason: He moved the

capital of Greece from Nafplion to Athens. His first task as king was to

make a detailed archaeological and topographical survey of Athens. He

assigned Gustav Eduard Schaubert and Stamatios Kleanthis to

complete this task. At that time Athens had a population of roughly

4,000 – 5,000 people, located mainly in what today covers the district of

Plaka in Athens.

Athens was chosen as the Greek capital for historical and sentimental reasons, not because it was a large city. A modern city plan was laid out and public buildings erected. The finest legacy of this period are the buildings of the University of Athens (1837), the Athens Polytechnic University (1837, under the name Royal School of Arts), the National Gardens of Athens (1840), the National Library of Greece (1842), the Old Royal Palace (now the Greek Parliament Building, 1843), the Old Parliament Building (1858). Schools and hospitals were established all over the (still small) Greek dominion; but the negative feelings of the people were rather neglecting this side of his reign.

In 1836 - 37, Otto visited Germany and married the beautiful and talented 17 year old, Duchess Amalia (Amelie) of Oldenburg (21 December 1818 - 20 May 1875). The wedding took place not in Greece, but in Oldenburg, on 22 November 1836; the marriage did not produce an heir and the new queen made herself unpopular by interfering in the government. Besides, she remained Protestant. Otto was unfaithful to his wife, and had a liaison with Jane Digby, a notorious woman his father had previously taken as a lover.

Meanwhile,

due to his overtly undermining the king, Armansperg was dismissed from

his duties by King Otto immediately on his return. However, despite high

hopes by the Greeks, the Bavarian Rundhart was

appointed chief minister and the granting of a Constitution was again

postponed. The attempts of Otto to conciliate Greek sentiment by efforts

to enlarge the frontiers of his kingdom, for example, by the suggested

acquisition of Crete in 1841, failed in their objective and only succeeded in embroiling him with the Great Powers.

Throughout his reign, King Otto found himself confronted by a recurring series of issues: partisanship of the Greeks, financial uncertainty, and ecclesiastical issues.

Greek parties in the Othonian era were based on two factors: the political activities of the diplomatic representatives of the Great Powers: Russia, United Kingdom and France and the affiliation of Greek political figures with these diplomats.

Financial uncertainty of the Othonian monarchy was the result of

- 1) Greece's poverty,

- 2) the concentration of land in the hands of a small number of wealthy “primates” like the Mavromichalis family of Mani, and

- 3) the promise of 60,000,000 francs in loans from the Great Powers, which kept these nations involved in Greek internal affairs and the Crown constantly seeking to please one or the other power to ensure the flow of funds.

The political machinations of the Great Powers were personified in their three legates in Athens: the French Theobald Piscatory, the Russian Gabriel Catacazy, and the English Edmund Lyons. They informed their home governments on the activities of the Greeks, while serving as advisers to their respective allied parties within Greece.

Otto pursued policies, such as balancing power among all the parties and sharing offices among the parties, ostensibly to reduce the power of the parties while trying to bring a pro - Othon party into being. The parties, however, became the entree into government power and financial stability.

The effect of his (and his advisors') policies was to make the Great Powers’ parties more powerful, not less. The Great Powers did not support curtailing Otto’s increasing absolutism, however, which resulted in a near permanent conflict between Otto’s absolute monarchy and the power bases of his Greek subjects.

Otto found himself confronted by a number of intractable ecclesiastical issues: 1) monasticism, 2) Autocephaly, 3) the king as head of the Church and 4) toleration of other churches.

His regents, Armansperg and Rundhart, established a controversial policy of suppressing the monasteries. This was very upsetting to the Church hierarchy. Russia was self - considered as stalwart defender of Orthodoxy but Orthodox believers were found in all three parties. Once he rid himself of his Bavarian advisers, Otto allowed the statutory dissolution of the monasteries to lapse.

By tradition dated back to the Byzantine era, the king was regarded by the Church as part of her head. On the issue of Church's Autocephaly and his role as king within the Church, Otto was overwhelmed by the arcana of Orthodox Church doctrine and popular discontent with his Roman Catholicism (while the Queen was Protestant).

In 1833, the regents had unilaterally declared the Autocephaly of the Church of Greece. This was a recognition of the de facto political situation, as the Patriarch of Constantinople was partially under the political control of the Ottoman Empire. However, faithful people - concerned that having a Catholic as the head of the Church of Greece would weaken the Orthodox Church - criticized the unilateral declaration of Autocephaly as non - canonical. For the same reason, they likewise resisted the foreign, mostly Protestant, missionaries who established schools throughout Greece.

Tolerance of other religions was over - supported by some in the English Party and others educated in the West as a symbol of Greece’s progress as a liberal European state. In the end, power over the Church and education was ceded to the Russian Party, while the King maintained a veto over the decision of the Synod of Bishops. This was to keep balance and avoid discrediting Greece in the eyes of Western Europe as a backward, religiously intolerant society.

Actually Greek society was very tolerant to other religions. But after 400 years of religious oppression by the Ottomans, Greeks were very suspicious of imposed "Liberal European progress". Such forced "progress" was viewed as one more attempt against their faith and against their own understanding of freedom, as the main motto of the Greek Revolution was "for the holy faith of Christ and the freedom of the homeland"; home and faith were inseparable, given also that the Church was the main contributor to the survival of the Greek language and Greek consciousness during Turkish occupation.

Catholic

communities were already established in Greece since the 13th century

(Athens, Cyclades, Chios, Crete). Jewish communities also existed in the

country, those arriving after the Expulsion of the Jews from Spain (1492) joining the earlier Romaniotes, Jews who had been living there since the times of Apostle Paul. Muslim

families were still living in Greece during Otto's reign, since

hostility was mainly against the Ottoman state and its depressive

mechanisms and not against Muslim people.

Although King Otto tried to function as an absolute monarch, as Thomas Gallant writes, he “was neither ruthless enough to be feared, nor compassionate enough to be loved, nor competent enough to be respected.”

By 1843, public dissatisfaction with him had reached crisis proportions and there were demands for a Constitution. Initially Otto refused to grant a Constitution, but as soon as German troops were withdrawn from the kingdom, a popular revolt was launched.

On 3 September 1843, the infantry led by Colonel Dimitris Kallergis and the respected Revolutionary captain and former President of the Athens City Council General Yiannis Makriyiannis assembled in the Square in front of the Palace in Athens.

Eventually joined by much of the population of the small capital, the rebellion refused to disperse until the King agreed to grant a Constitution, which would require that there be Greeks in the Council, that he convene a permanent National Assembly and that Otto personally thank the leaders of the uprising.

Left with little recourse, now that his German troops were gone, King Otto gave in to the pressure and agreed to the demands of the crowd over the objections of his opinionated Queen. This square was renamed Constitution Square (Πλατεία Συντάγματος) to commemorate (until today) the events of September 1843 (and to feature many later tumultuous events of Greek history). Now for the first time the king had Greeks in his Council and the French party, the English Party and the Russian Party (according to which of the Great Powers’ culture they most esteemed) vied for rank and power.

The King’s prestige, which was based in large part on his support by the combined Great Powers, but mostly the support of the British, suffered in the Pacifico incident of 1850, when British Foreign Secretary Palmerston sent the British fleet to blockade the port of Piraeus with warships, to exact reparation for injustice done to a British subject.

The Great Idea (Μεγάλη Ιδέα), the dream of uniting all Greek populations of the Ottoman Empire, thereby restoring the Byzantine Empire under Christian rule, led to his contemplating to enter the Crimean War at the side of Russia against Turkey and its British and French allies in 1853; the enterprise was unsuccessful, and resulted in renewed intervention by the two Great Powers and a second blockade of Piraeus port, forcing Greece to neutrality.

In 1861, a student named Aristeidis Dosios (son of politician Konstantinos Dosios) attempted to murder Queen Amalia,

and was openly hailed as a hero. His attempt, however, also prompted

spontaneous feelings of monarchism and sympathy towards the royal couple

among the Greek population.

It is well known that Otto was a great admirer of the rural Sarakatsani, a nomadic group of Greek mountain shepherds thought by some scholars to be descended from the Dorians. It is believed that at an early age he fathered an illegitimate child in the Sarakatsani clan named "Tangas". This child was named Manoli Tangas, was brought to Athens and remained there after Otto's 1862 departure, living as a merchant trader with children of his own. The descendants of Manoli still reside in Athens today.

However, since Otto had no legitimate issue, he chose his brother as Crown Prince of Greece. It is often suggested that following his death, Prince Adalbert became the heir presumptive to the throne of Greece. In fact, rights to the Greek succession were passed onto his other older brother Luitpold, who technically succeeded to the Greek throne in 1867.

Due to the renunciation of all the rights to the Greek succession by King Ludwig III, at Luitpold's death the rights to the throne of Greece were inherited by his second son, Prince Leopold.

While on a visit to the Peloponnese in 1862 a new coup was launched and this time a Provisional Government was set up and summoned a National Convention. Ambassadors of the Great Powers urged King Otto not to resist, and the king and queen took refuge on a British warship and returned to Bavaria the same way they had come to Greece (aboard a British warship), taking with them the Greek royal regalia which he had brought from Bavaria in 1832. It has been suggested that had Otto and Amalia borne an heir, then the King would not have been overthrown, as succession was also a major unresolved question at the time. It is also true, however, that the Constitution of 1843 made provision for his succession by his two younger brothers and their descendants.

He died in the palace of the former bishops of Bamberg, Germany, and was buried in the Theatiner Church in Munich. During his retirement, he would still wear the traditional uniform nowadays worn only by the evzones (Presidential Guards). During the rebellion in Crete against the Ottoman Empire in 1866, Otto donated most of his fortune to support the revolt by supplying it with weapons. He also made provisions for his donation to be kept secret until his death, to avoid causing political problems to the new King, George I.

It

is generally accepted by historians that, although Otto failed, he

deeply loved Greece as his own new homeland. His failure was mainly a

result of the continuous intrigues and competition among the three Great

Powers. Before his death, Otto asked to be buried in his own Greek

traditional uniform.

Andreas Metaxas (Greek: Ανδρέας Μεταξάς) (1790 - September 19, 1860) was a Greek politician born on the island of Cephalonia.

During the latter part of the War of Independence (1824 - 1827) he accompanied Kapodistrias to Greece, and was appointed by him Minister of War. He was a devout supporter of Kapodistrias and after his assassination in 1831, Metaxas became a member of the provisional government which held office till the accession of King Otto in 1833. During the minority of Otto he was named privy councilor and minister at Madrid and Lisbon. He was a leader in the so-called Russian Party which was the most conservative of the three early parties.

In 1840 he was recalled and appointed minister of war. Having come to power in the 3 September 1843 Revolution, in 1843 - 1844 he was president of the Council of Ministers (Prime Minister), and he subsequently held the post of ambassador at Constantinople from 1850 to 1854. He died in Athens in 1860.