<Back to Index>

- Prime Minister of Greece Theodoros Deliyannis (Θεόδωρος Δηλιγιάννης), 1820

PAGE SPONSOR

Theodoros Deligiannis, also spelled Delijannis and Deliyannis, (Greek: Θεόδωρος Δηλιγιάννης, 2 January 1820 – 13 June 1905), was a Greek statesman.

He was born at Lagkadia, Arcadia. He studied law in Athens, and in 1843 entered the Ministry of the Interior, of which department he became permanent secretary in 1859. In 1862, on the deposition of King Otto, he became minister of foreign affairs in the provisional government. In 1867, he was Greek Minister at Paris. On his return to Athens he became a member of successive cabinets in various capacities, and rapidly collected a party around him consisting of those who opposed his great rival, Charilaos Trikoupis. He eventually became the leader of the Nationalist Party after Alexandros Koumoundouros.

In the so-called Ecumenical Ministry of 1877 he voted for war with Turkey, and on its fall he entered the cabinet of Koumoundoros as minister of foreign affairs. He was a representative of Greece at the Berlin Congress in 1878. From this time forward, and particularly after 1882, when Trikoupis again came into power at the head of a strong party, the duel between these two statesmen was the leading feature of Greek politics.

Deligiannis first formed a cabinet in 1885; but his warlike policy, the aim of which was, by threatening Turkey, to force the Great Powers to

make concessions in order to avoid the risk of a European war, ended in

failure. For the powers, in order to stop his excessive armaments,

eventually blockaded the Piraeus and

other ports, and this brought about his downfall. He returned to power

in 1890, with a radical program, but his failure to deal with the

financial crisis produced a conflict between him and the king, and his

disrespectful attitude resulted in his summary dismissal in 1892.

Deligiannis evidently expected the public to side with him; but at the

elections he was badly beaten.

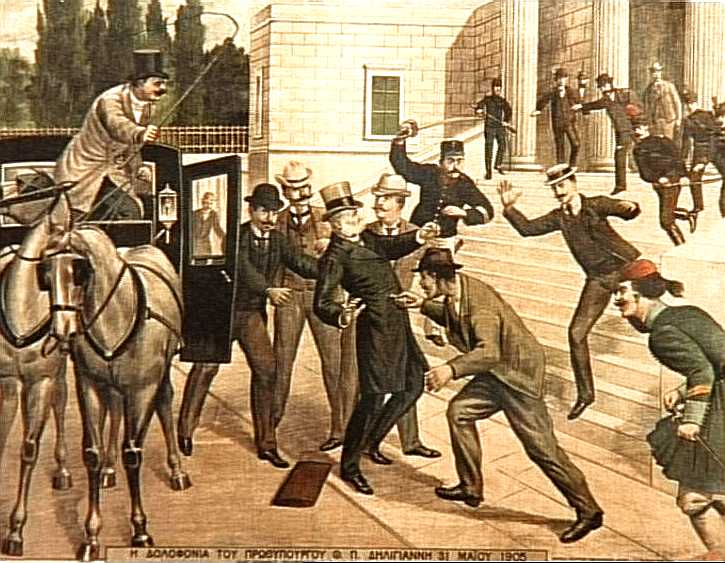

In 1895, however, he again became prime minister, and was at the head of affairs during the Cretan crisis and the opening of the war with Turkey in 1897. The easy defeat which ensued, though Deligiannis himself had been led into the disastrous war policy to some extent against his will, caused his fall in April 1897, the king again dismissing him from office when he declined to resign. Delyannis kept his own seat at the elections of 1899, but his following dwindled to a small percentage. He quickly recovered his influence, however, and he was again president of the council and minister of the interior when, on the 13 June 1905, he was assassinated in revenge for having implemented severe anti - gambling regulations. His attacker, a professional gambler named Gherakaris, stabbed him with a dagger in the abdomen as he was entering Parliament. The incident took place at 5pm; an emergency operation failed to stop his internal bleeding and Deligiannis died at 7.30pm.

The main fault of Deligiannis as a statesman was that he was unable to grasp the truth that the prosperity of a state depends on its adapting its ambitions to its means. Yet, in his vast projects, which the powers were never likely to endorse, and, as a result, were likely to remain unfulfilled, he represented the real wishes and aspirations of his countrymen and his death was the occasion for an extraordinary demonstration of popular grief. He died in extreme poverty, and a pension was voted to support the two nieces who lived with him.