<Back to Index>

- Prime Minister of Greece Nikolaos Plastiras (Νικόλαος Πλαστήρας), 1883

- Prime Minister of Greece Alexander Papagos (Αλέξανδρος Παπάγος), 1883

PAGE SPONSOR

Nikolaos Plastiras (Greek: Νικόλαος Πλαστήρας) (November 4, 1883 – July 26, 1953) was a Greek general and politician, who served thrice as Prime Minister of Greece. A distinguished soldier and known for his personal bravery, he was known as "O Mavros Kavalaris" ("The Black Rider") during the Greco - Turkish War of 1919 - 1922. After the Greek defeat in the war, along with other Venizelist officers he staged a coup against King Constantine I of Greece and his government. The military led government ruled until January 1924, when power was handed over to an elected National Assembly, which later declared the Second Hellenic Republic. In the interwar period, Plastiras remained a devoted Venizelist and republican. Trying to avert the rise of the royalist People's Party and the restoration of the monarchy, he led two coup attempts in 1933 and 1935, both of which failed, forcing him to exile in France.

During the Axis Occupation of Greece in the Second World War he was the nominal leader of the EDES resistance group, although he remained in exile in Marseilles. After the occupation, he returned to Greece and served as a centrist Prime Minister three times, often in coalition with the Liberal Party. In his last two governments, he tried to heal the rift caused in Greek society by the Greek Civil War, but was unsuccessful.

He was born in 1883, in Karditsa, Greece. Plastiras' parents were originally from Morfovouni (formerly Vounesi), a village in the Agrafa mountains of southwestern Thessaly. The municipality was renamed for General Plastiras and Morfovouni is the present capital of Plastiras Municipality. The family moved to Karditsa before Plastiras was born.

After finishing school in Karditsa, he joined the 5th Infantry Regiment as a volunteer in 1904. He fought in the Macedonian Struggle, and participated in the military coup of 1909. He entered the NCO School in 1910 and, after being assigned to the rank of 2nd Lieutenant in 1912, he fought with distinction in the Balkan Wars, where he earned his nickname "The Black Rider". He first rose to wider prominence when, as a Major, he supported the Movement of National Defense of Eleftherios Venizelos during the First World War. He fought with distinction with the 5/42 Evzone Regiment at the battle of Skra - di - Legen and was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. In 1919, Colonel Plastiras commanded the 5/42 Evzone Regiment in the Ukraine, as part of an Allied force aiding the White Army in their ultimately unsuccessful fight against the Red Army. His force was then transferred to Smyrna in Asia Minor via Romania.

During the botched war with Turkey from 1919 – 1922, the Turks called Plastiras Kara Biber ("The Black Pepper"), while the 5/42 Evzones became known as the Şeytan Asker ("Satan's Army"). His advance was finally halted at Kale - Grotso, just across the Sakarya River. Soon after, at the battle of Sakarya, the Greeks were forced to begin their retreat. After the Turkish breakthrough in August 1922, Colonel Plastiras' unit was among the few retaining any coherence, withdrawing orderly to the coast, fighting off superior Turkish forces, rallying around him men from other units and saving several thousands of Anatolian Greeks along the way. For these feats he earned immense popularity, especially among the Ionian Greeks he helped save. The remnants of the Greek Army made their way to the islands of the Eastern Aegean, where the Army's resentment at the political leadership in Athens resulted in the outbreak of the 1922 Revolution on September 11, led by Plastiras, Colonel Stylianos Gonatas and Commander Phokas.

Having the support of the Army and much of the people, the Revolution quickly assumed control of the country. Plastiras forced King Constantine to resign, called upon the exiled Venizelos to lead the negotiations with Turkey which culminated in the Treaty of Lausanne, and set about to reorganize the Army to protect the Evros line against any Turkish advance into Western Thrace. One of the most controversial acts of the revolutionary government was the trial and execution of five royalist politicians, including former PM Dimitrios Gounaris and the former Commander - in - Chief, General Georgios Hatzianestis, on November 28, 1922 as those mainly responsible for the Asia Minor Disaster, in the infamous "Trial of the Six".

Plastiras faced multiple challenges in governing Greece. The 1.3 million refugees from the population exchange had to be catered for in a country with a ruined economy, internationally isolated and internally divided. The Corfu incident, and a botched Royalist coup in October 1923 were evidence of this. After the failed royalist coup, King George II was forced to leave the country. Nonetheless, he managed to restore some order to the state and to lay the groundwork for the Second Hellenic Republic. After the elections of December 1923 for the new National Assembly, he resigned from the Army on January 2, 1924, retiring to private life. In recognition of his services to the country, the National Assembly declared him "worthy of the fatherland" and conferred to him the rank of Lieutenant General in retirement.

Plastiras

was even admired by his greatest enemy, Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk).

At the end of the war, during the negotiations that took place regarding

the exchange of populations between Greece and the newly formed

Republic of Turkey, Atatürk is quoted telling Plastiras, "I gave

gold and you gave me copper."

The Republic that he had helped found proved an unstable one. Coups, counter coups, the conflict between Venizelists / Republicans and Royalists, and constant economic problems plagued Greece. Plastiras, persecuted during the Pangalos dictatorship, attempted to lead a coup in March 1933, after the anti - Venizelists won the elections, but facing universal reaction (even from Venizelos himself), he was forced to flee abroad. Finally, after the failed Venizelist revolt of 1935, although still abroad, he was condemned in absentia to death. Nonetheless he maintained a high prestige as a war hero and because of his integrity and staunch Republicanism. From his French exile, he watched the Germans overrun Greece, and played a role in the creation of the EDES resistance group, whose titular leadership he had.

He returned to Greece in 1945, after his selection as prime minister following the December events of 1944, primarily because he was a commonly accepted personality. Plastiras attempted to tread a middle path between the British, who were supporting the returned government - in - exile and the return of King George II, and the democratic leftist guerilla of the EAM / ELAS. During his premiership, the Varkiza Agreement was signed. His moderate policies and republican sympathies earned the distrust of the British, and he was dismissed after only three months in office.

In 1949, after the end of the Greek Civil War, Plastiras founded a new party, the National Progressive Center Union (Εθνική Προοδευτική Ένωση Κέντρου,

EPEK), forming a following of disappointed Liberals and left leaning

democrats. He preached a message of national reconciliation, which put

him in conflict with the conservative establishment which sought to

punish those who had fought to establish a communist government.

Together with Sofoklis Venizelos and George Papandreou,

Plastiras formed a coalition government in 1950, which fell, however,

when his partners retired. In the September 1951 elections, EPEK emerged

as the strongest of the centrist parties. Plastiras formed a coalition

government with Sofoklis Venizelos'

Liberals, and attempted to address the great problems of the country.

His government initiated the economic recovery and the reconstruction of

Greece. A monument to this is the construction of the dam at the Tavropos (Megdovas) River to form a lake, a program that he initiated. The lake and

dam, both formerly named Tavropos, now bear his name. His policy of

conciliation, however, was bitterly assailed from the right, distrusted

from the left, and undermined even by members of his own cabinet. A

defining moment of his failure was the conviction and execution of Nikos Belogiannis in

March 1952. After losing the elections of November 1952, his political

career, and with it the liberal 'Centrist Intermission', came to an end.

He died in poverty in 1953 in Athens.

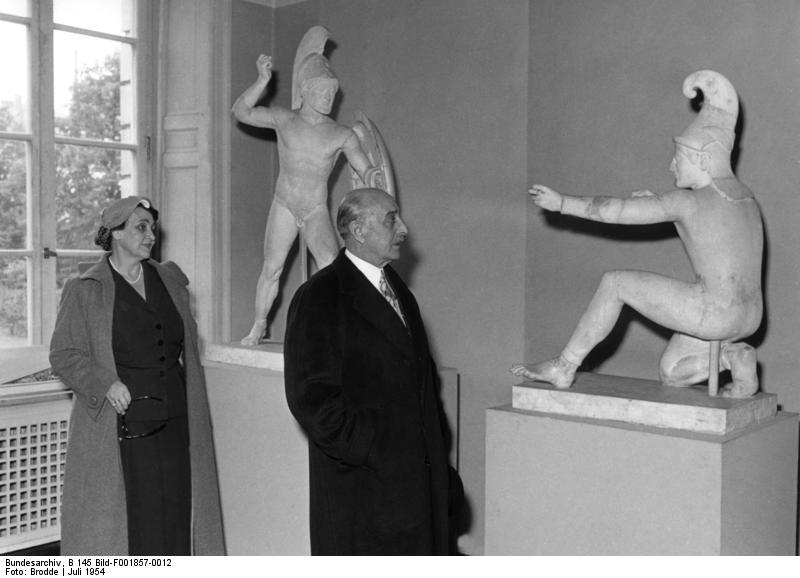

Field Marshal Alexander Papagos (Greek: Αλέξανδρος Παπάγος, 9 December 1883, Athens – 4 October 1955, Athens), was a Greek General who led the Greek Army in the Greco - Italian War and the later stages of the Greek Civil War and became the country's Prime Minister. His premiership was defined by the Cold War; American military bases were allowed on Greek territory, a powerful and vehemently anti - communist security apparatus was created, and the communist leader Nikos Ploumpidis was executed by firing squad.

His father was Major General Leonidas Papagos, who occupied very important posts during his military career, including Director of personnel (prosoparchis) at the War Ministry and aide - de - camp to the King. His ancestry was partly Vlach and partly from Syros. He studied in the Brussels Military Academy and the Cavalry School at Ypres, joining the Hellenic Army in 1906 as a Cavalry 2nd Lieutenant.

In the First Balkan War he served as a junior officer in the General Staff of King Constantine. As a captain, he held successive staff positions as well as taking part in the Siege of Yannina (Ioannina) and fighting in Macedonia from November 1912 until March 1913. He was a confirmed royalist, so when the King was deposed in 1917, he was dismissed from the Army along with many other officers. He was recalled after the return of King Constantine in 1920.

He served as operations officer to the Cavalry Brigade in the disastrous Asia Minor Campaign and was decommissioned after the ruling government was forced out by a revolutionary council headed by Nikolaos Plastiras. He was again recalled in 1927 with the rank of Major General and promoted to Lieutenant General in 1931 and Corps Commander in 1934. In October 1935, as a Lieutenant General and Chief of the Army, along with the chiefs of the Navy and the Air Force, he helped topple the government of Panagis Tsaldaris and declared the restoration of the monarchy, allowing for the return of King George II. He was appointed Minister of War in the Georgios Kondylis, Konstantinos Demertzis and Ioannis Metaxas governments. From his position, he employed the Army to support Metaxas' declaration of dictatorship in 4 August 1936.

During the next years, as Chief of the General Staff, he actively tried to reorganize and reequip the Army for the oncoming war. At the outbreak of the Greco - Italian War on October 28, 1940, he was Commander - in - Chief and directed Greek operations against Italy along the Greek - Albanian border. The Greek army, under his command, managed to halt the Italian advance by 8 November and forced them to withdraw deep into Albania between 18 November and 23 December. The successes of the Greek Army brought him fame and applause. Time Magazine placed him on its cover, as Papagos 'Commander of the Greeks' on 10 December 1949. A second Italian offensive between 9 and 16 March 1941 was repulsed. Despite this success, Papagos was forced to maintain the bulk of the Greek Army in Albania, and was unwilling to order a gradual withdrawal to reinforce the north - eastern border as German intervention came closer.

After the German invasion on 6 April 1941, outnumbered Greek forces in Macedonia fiercely resisted the German offensive at the so-called Metaxas Line, but were outflanked and Papagos endorsed their surrender. Soon after the Army of Epirus capitulated and by 23 April the Greek government was forced to flee to Crete. Papagos remained behind and in July 1943, together with other generals, he was arrested and sent to concentration camps in Germany. In late April 1945 he was transferred to Tyrol together with about 140 other prominent inmates of the Dachau concentration camp, where the SS left the prisoners behind. He was liberated by the Fifth U.S. Army on 5 May 1945.

In 1945 he returned to Greece, rejoined the Army and reached the rank of full General in 1947. In August 1945, he was appointed an Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire by the British. On 29 January 1949, he was once again appointed Commander - in - Chief, to defeat the Communists in the Greek Civil War. This he achieved, with extensive American aid, including napalm equipped aircraft, and the extensive deployment of Special Forces (LOK), during the Grammos - Vitsi campaign between February to October of that year. As a reward for his services, he was awarded the title of Marshal on 28 October 1949. His is the only Greek career officer to ever hold this rank.

He continued to serve in his capacity as Commander - in - Chief until 1951,

while Greece was in a state of political instability, with splinter

parties and weak politicians unable to provide a firm government.

In May 1951 he resigned from the Army in order to become involved in politics. He founded the Greek Rally (Ελληνικός Συναγερμός), modeled after De Gaulle's Rassemblement du Peuple Français and won the September elections with 36.53 percent of the vote, largely due to his popularity, his image as a strong and determined leader, and the communist defeat in the civil war, which was attributed in great part to his leadership. Despite this victory, Papagos was unable to form a government on this majority, and had to wait until the November 1952 elections, in which his party tallied an impressive 49 percent of the popular vote, gaining 239 out of 300 seats in Parliament. The Field Marshal, with his popular backing and United States support, was an authoritative figure, leading to friction with the Royal Palace. Papagos' government successfully strove to modernize Greece (where the young and energetic Minister of Public Works, Constantine Karamanlis, first distinguished himself) and restore the economy of a country ruined by 10 years of war, but was criticized by the opposition for doing little to restore social harmony in a country still scarred from the civil war.

One of the major issues faced by Papagos was the Cyprus problem, where the Greek majority had begun clamoring for Enosis (Union) with Greece. In response to demonstrations in the streets of Athens, Papagos reluctantly, as this would put Greece in confrontation with Great Britain, ordered Greece's UN representative in August 1954 to raise the issue of Cyprus before the UN General Assembly. When the EOKA campaign began in 1955, Papagos was in declining health and unwilling to act. The clashes in Cyprus, however, led to a deterioration of Greco - Turkish relations, culminating in the Istanbul Pogrom in September. By that time, Papagos was ill, and on 4 October 1955, he died.

The Athens suburb of Papagou, where the Ministry of Defense is located, is named after him.