<Back to Index>

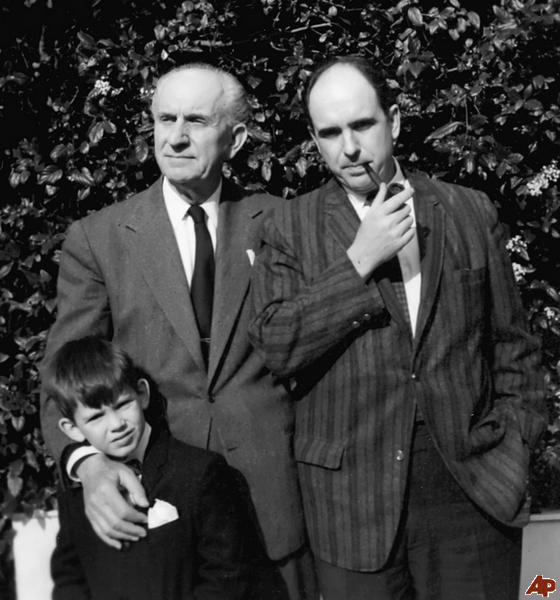

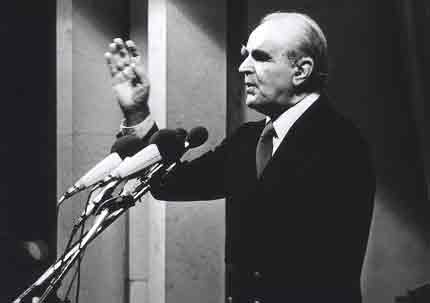

- President of the Hellenic Republic Konstantinos Karamanlis (Κωνσταντίνος Καραμανλής), 1907

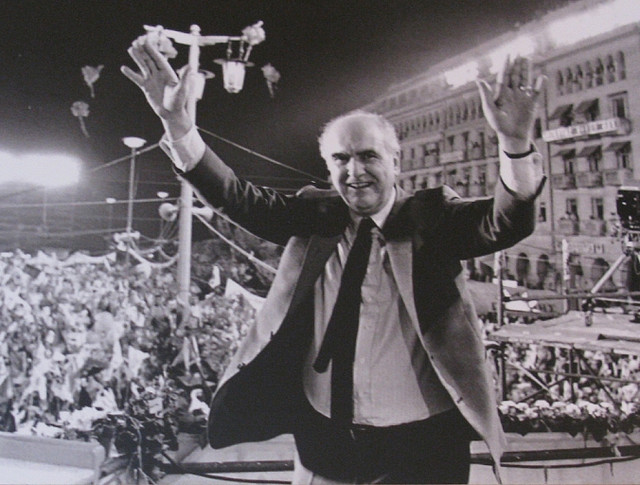

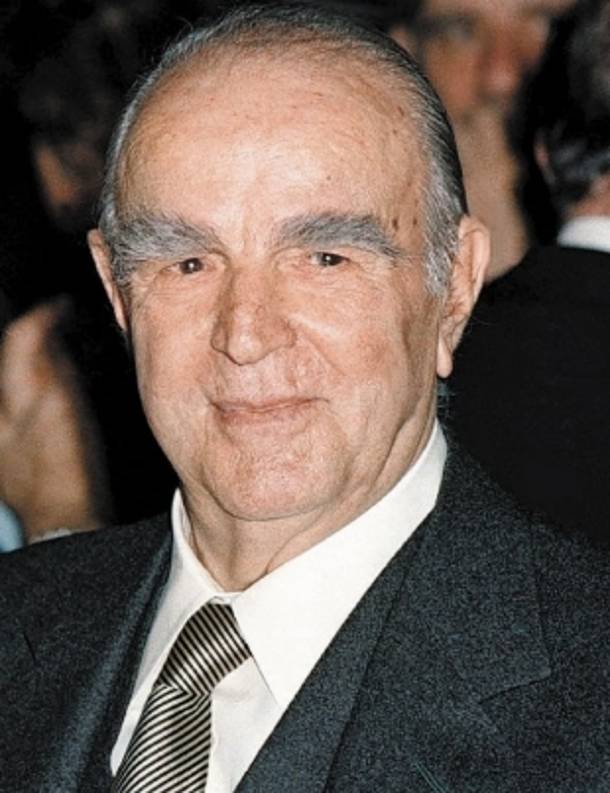

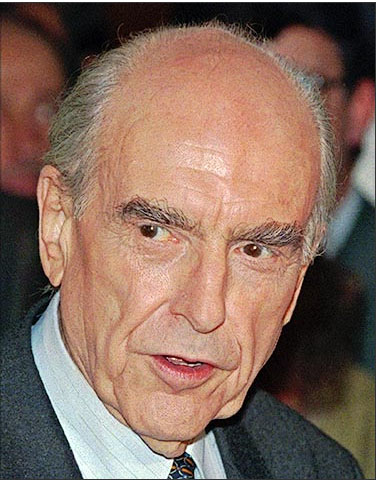

- Prime Minister of Greece Andreas Papandreou (Ανδρέας Παπανδρέου), 1919

PAGE SPONSOR

Konstantínos G. Karamanlís (Greek: Κωνσταντίνος Γ. Καραμανλής) (8 March 1907 – 23 April 1998), commonly anglicized to Constantine Karamanlis or Caramanlis, was a four time Prime Minister, the 3rd and 5th President of the Third Hellenic Republic and a towering figure of Greek politics whose political career spanned much of the latter half of the 20th century.

He was born in the village of Proti, Macedonia, Ottoman Empire (now Greece). He became a Greek citizen in 1913, after Macedonia was united with Greece in the aftermath of the Second Balkan War. His father was Georgios Karamanlis, a teacher who fought during the Greek Struggle for Macedonia, in 1904 – 1908. After spending his childhood in Macedonia, he went to Athens to attain his degree in Law. He practiced law in Serres, entered politics with the conservative People's Party and was elected Member of Parliament for the first time at the age of 28, in the Greek legislative election, 1936. Due to health problems, Karamanlis did not participate in the Greco - Italian War.

After World War II, Karamanlis quickly rose through the ranks of Greek politics. His rise was strongly supported by fellow party member and close friend Lambros Eftaxias who served as Minister for Agriculture under the premiership of Konstantinos Tsaldaris. Karamanlis's first cabinet position was Minister for Employment in 1947 under the same administration. Karamanlis eventually became Minister of Public Works in the Greek Rally administration under Prime Minister Alexandros Papagos. He won the admiration of the US Embassy for the efficiency with which he built road infrastructure and administered American aid programs.

When Alexandros Papagos died after a brief illness (1955), King Paul of Greece appointed the 48 year old Karamanlis as Prime Minister. The King did so, thus bypassing Stephanos Stephanopoulos and Panagiotis Kanellopoulos, the two senior Greek Rally politicians who were widely considered as the heavyweights most likely to succeed Papagos. Karamanlis first became prime minister in 1955, and reorganized the Greek Rally as the National Radical Union. One of the first bills he promoted as Prime Minister implemented the extension of full voting rights to women, which stood dormant although nominally approved in 1952. Karamanlis won three successive elections (1956, 1958 and 1961).

In

1959 he announced a five year plan (1960 – 64) for the Greek economy,

emphasizing improvement of agricultural and industrial production, heavy

investment on infrastructure and the promotion of tourism. On the

international front, Karamanlis abandoned the government's previous

strategic goal for enosis (the unification of Greece and Cyprus) in favor of independence for Cyprus. In 1958, his government engaged in negotiations with the United Kingdom and Turkey, which culminated in the Zurich Agreement as a basis for a deal on the independence of Cyprus. In 1959 the plan was ratified in London by Makarios III.

Max Merten was Kriegverwaltungsrat (military administration counselor) of the Nazi German occupation forces in Thessaloniki. He was convicted in Greece and sentenced to a 25 year term as a war criminal in 1959. On 3 November of that year, Merten benefited from an amnesty for war criminals, and was set free and extradited to the Federal Republic of Germany, after political and economic pressure from West Germany (which, at the time, hosted thousands of Greek economic immigrants). Merten's arrest also enraged Queen Frederica, a woman with German ties, who wondered whether "this is the way mister district attorney understands the development of German and Greek relations".

In Germany, Merten was eventually acquitted from all charges due to "lack of evidence." On 28 September 1960 German newspapers Hamburger Echo and Der Spiegel published excerpts of Merten's deposition to the German authorities where Merten claimed that Karamanlis, the then Minister for the Interior Takos Makris and his wife Doxoula (whom he described as Karamanlis's niece) along with then Deputy Minister of Defense George Themelis were informers during the Nazi occupation of Greece. Merten alleged that Karamanlis and Makris were rewarded for their services with a business in Thessaloniki which belonged to a Greek Jew sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp. He also alleged that he had pressured Karamanlis and Makris to grant amnesty and release him from prison.

Karamanlis rejected the claims as unsubstantiated and absurd, and accused Merten of attempting to extort money from him prior to making the statements. The West German government also decried the accusations as calumniatory and libelous. Karamanlis accused the opposition party of instigating a smear campaign against him. Although Karamanlis never pressed charges against Merten, charges were pressed in Greece against Der Spiegel by Takos and Doxoula Makris and Themelis, and the magazine was found guilty for slander in 1963. Merten did not appear to testify during the Greek court proceedings. The Merten Affair remained at the center of political discussions until early 1961.

Merten's

accusations against Karamanlis were never corroborated in a court of

law. Historian Giannis Katris, an ardent critic of Karamanlis, has

argued that Karamanlis should have resigned the premiership and pressed

charges against Merten as a private individual in German courts, in

order to fully clear his name. Nonetheless, Katris rejects the

accusations as "unsubstantiated" and "obviously fallacious".

Karamanlis as early as 1958 pursued an aggressive policy toward Greek membership in the EEC. He considered Greece's entry into the EEC a personal dream because he saw it as the fulfillment of what he called "Greece's European Destiny". He personally lobbied European leaders, such as Germany's Konrad Adenauer and France's Charles de Gaulle followed by two years of intense negotiations with Brussels. His intense lobbying bore fruit and on 9 July 1961 his government and the Europeans signed the protocols of Greece's Treaty of Association with the European Economic Community (EEC). The signing ceremony in Athens was attended by top government delegations from the six member bloc of Germany, France, Italy, Belgium, Luxemburg and the Netherlands, a precursor of the European Union. Economy Minister Aristidis Protopapadakis and Foreign Minister Evangelos Averoff were also present. German Vice Chancellor Ludwig Erhard and Belgian Foreign Minister Paul - Henri Spaak, a European Union pioneer and a Karlspreis winner like Karamanlis, were among the European delegates.

This had the profound effect of ending Greece's economic isolation and breaking its political and economic dependence on US economic and military aid, mainly through NATO. Greece became the first European country to acquire the status of associate member of the EEC outside the six nation EEC group. In November 1962 the association treaty came into effect and envisaged the country's full membership at the EEC by 1984, after the gradual elimination of all Greek tariffs on EEC imports. A financial protocol clause included in the treaty provided for loans to Greece subsidized by the community of about $300 million between 1962 and 1972 to help increase the competitiveness of the Greek economy in anticipation of Greece's full membership. The Community's financial aid package as well as the protocol of accession were suspended during the 1967 – 74 junta years and Greece was expelled from the EEC. As well, during the dictatorship, Greece resigned its membership in the Council of Europe fearing embarrassing investigations by the Council, following torture allegations.

Soon after returning to Greece during metapolitefsi Karamanlis reactivated his push for the country's full EEC membership in 1975 citing political and economic reasons. Karamanlis was convinced that Greece's membership in the EEC would ensure political stability in a nation having just undergone a transition from dictatorship to Democracy.

In

May 1979 he signed the full treaty of accession. Greece became the

tenth member of the EEC on 1 January 1981 three years earlier than the

original protocol envisioned and despite the freezing of the treaty of

accession during the junta (1967 – 1974).

In the 1961 elections, the National Radical Union won 50.80 percent of the popular vote. On 31 October, George Papandreou stated that the electoral results were due to widespread vote rigging and fraud. Karamanlis replied electoral fraud, to the extent that it happened, was masterminded by the Palace. Political tension escalated, as Papandreou refused to recognize the Karamanlis government. On 14 November 1961 he initiated an "unrelenting struggle" ("ανένδοτο αγώνα") against Karamanlis.

Tension between Karamanlis and the Palace escalated even further as Karamanlis vetoed fundraising initiatives undertaken by Queen Frederika. On 17 June 1963 Karamanlis resigned the premiership after a disagreement with King Paul of Greece, and spent four months abroad. In the meantime the country was in turmoil following the assassination of Dr. Gregoris Lambrakis, a leftist member of Parliament, by right wing extremists during a pro-peace demonstration in Thessaloniki. The opposition parties castigated Karamanlis as a moral accomplice to the assassination.

In the 1963 election the National Radical Union, under his leadership, was defeated by the Center Union under George Papandreou. Disappointed with the result, Karamanlis fled Greece under the name Triantafyllides. He spent the next 11 years in self imposed exile in Paris, France. Karamanlis was succeeded by Panagiotis Kanellopoulos as the ERE leader.

In 1966, Constantine II of Greece sent his envoy Demetrios Bitsios to Paris on mission to convince Karamanlis to return to Greece and resume a role in Greek politics. According to uncorroborated claims made by the former monarch only after both men had died, in 2006, Karamanlis replied to Bitsios that he would return under the condition that the King were to impose martial law, as was his constitutional prerogative.

U.S. journalist Cyrus L. Sulzberger has separately claimed that Karamanlis flew to New York to visit Lauris Norstad and lobby U.S. support for a coup d'état in Greece that would establish a strong conservative regime under himself; Sulzberger alleges that Norstad declined to involve himself in such affairs.

Sulzberger's account, which unlike that of the former King was delivered during the lifetime of those implicated (Karamanlis and Norstad), rested solely on the authority of his and Norstad's word.

When in 1997 the former King reiterated Sulzberger's allegations, Karamanlis stated that he "will not deal with the former king's statements because both their content and attitude are unworthy of comment." The deposed King's adoption of Sulzberger's claims against Karamanlis was castigated by left leaning media, typically critical of Karamanlis, as "shameless" and "brazen". It bears noting that, at the time, the former King referred exclusively to Sulzberger's account, to support the theory of a planned coup by Karamanlis, and made no mention of the alleged 1966 meeting with Bitsios, which he would refer to only after both participants had died and could not respond.

On 21 April 1967, constitutional order was usurped by a coup d'état led by officers around Colonel George Papadopoulos. The King accepted to swear in the military appointed government as the legitimate government of Greece, but launched an abortive counter coup to overthrow the junta eight months later. Constantine and his family then fled the country.

In 2001, former agents of the Eastern German secret police Stasi,

claimed to Greek investigative reporters that during the Cold War, they

had orchestrated an operation of evidence falsification, in order to present Constantine Karamanlis as having planned a coup and thus damage his reputation, in an apparent disinformation propaganda campaign. The operation allegedly centered on a falsified conversation between Karamanlis and Strauss, a Bavarian officer of the King. They also alleged that a photograph of the former New Democracy leader Constantine Mitsotakis standing next to a uniformed Nazi officer, that had been repeatedly published by the PASOK leaning Greek daily Avriani, was in fact a photomontage fabricated in Bulgaria. Their disclosures have not been challenged to this day.

Following the invasion of Cyprus by the Turks, the dictators finally abandoned Ioannides and his disastrous policies. On 23 July 1974, President Phaedon Gizikis called a meeting of old guard politicians, including Panagiotis Kanellopoulos, Spiros Markezinis, Stephanos Stephanopoulos, Evangelos Averoff and others. The heads of the armed forces also participated in the meeting. The agenda was to appoint a national unity government that would lead the country to elections.

Former Prime Minister Panagiotis Kanellopoulos was originally suggested as the head of the new interim government. He was the interim Prime Minister originally deposed by the dictatorship in 1967 and a distinguished politician who had repeatedly criticized Papadopoulos and his successor. Raging battles were still taking place in Cyprus' north when Greeks took to the streets in all the major cities, celebrating the junta's decision to relinquish power before the war in Cyprus could spill all over the Aegean. But talks in Athens were going nowhere with Gizikis' offer to Panagiotis Kanellopoulos to form a government.

Nonetheless, after all the other politicians departed without reaching a decision, Evangelos Averoff remained in the meeting room and further engaged Gizikis. He insisted that Karamanlis was the only political personality who could lead a successful transition government, taking into consideration the new circumstances and dangers both inside and outside the country. Gizikis and the heads of the armed forces initially expressed reservations, but they finally became convinced by Averoff's arguments. Admiral Arapakis was the first, among the participating military leaders, to express his support for Karamanlis.

After Averoff's decisive intervention, Gizikis decided to invite Karamanlis to assume the premiership. Throughout his stay in France, Karamanlis was a vocal opponent of the Regime of the Colonels, the military junta that seized power in Greece in April 1967. Now he was called to end his self imposed exile and restore Democracy to the place that originally created it: Greece. Upon news of his impending arrival cheering Athenian crowds took to the streets chanting: Έρχεται! Έρχεται! He is coming! He is coming! Similar celebrations broke out all over Greece. Athenians in their thousands also went to the airport to greet him. Karamanlis was sworn in as Prime Minister under President pro tempore Phaedon Gizikis who remained in power in the interim, till December 1974, for legal continuity reasons until a new constitution could be enacted during metapolitefsi, and was subsequently replaced by duly elected President Michail Stasinopoulos.

During the inherently unstable first weeks of the metapolitefsi, Karamanlis was forced to sleep aboard a yacht watched over by a destroyer for the fear of a new coup. Karamanlis attempted to defuse the tension between Greece and Turkey, which were on the brink of war over the Cyprus crisis, through the diplomatic route. Two successive conferences in Geneva, where the Greek government was represented by George Mavros, failed to avert a full scale invasion and occupation of 37 percent of Cyprus by Turkey on 14 August 1974.

The steadfast process of transition from military rule to a pluralist democracy proved successful. During this transition period of the metapolitefsi, Karamanlis legalized the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) that was banned decades ago. The legalization of the communist party was considered by many as a gesture of political inclusionism and rapprochement. At the same time he also freed all political prisoners and pardoned all political crimes against the junta. Following through with his reconciliation theme he also adopted a measured approach to removing collaborators and appointees of the dictatorship from the positions they held in government bureaucracy, and declared that free elections would be held in November 1974, four months after the collapse of the Regime of the Colonels.

In the 1974 elections, Karamanlis with his newly formed conservative party, named New Democracy obtained a massive parliamentary majority and was elected Prime Minister. The elections were soon followed by the 1974 plebiscite on the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the Hellenic Republic, the televised 1975 trials of the former dictators (who received death sentences for high treason and mutiny that were later commuted to life incarceration) and the writing of the 1975 constitution.

In 1977, New Democracy again won the elections, and Karamanlis continued to serve as Prime Minister until 1980.

Under

Karamanlis's premiership, his government undertook numerous

nationalizations in several sectors, including banking and

transportation. Karamanlis's policies of economic statism, which fostered a large state run sector, have been described by many as socialmania.

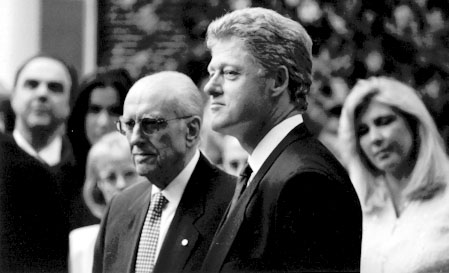

Following his signing of the Accession Treaty with the European Economic Community (now the European Union) in 1979, Karamanlis relinquished the Premiership and was elected President of the Republic in 1980 by the Parliament, and in 1981 he oversaw Greece's formal entry into the European Economic Community as its tenth member. He served until 1985 then resigned and was succeeded by Christos Sartzetakis.

In

1990 he was re-elected President by a conservative parliamentary

majority (under the conservative government of then Prime Minister Konstantinos Mitsotakis) and served until 1995, when he was succeeded by Kostis Stephanopoulos.

Karamanlis retired in 1995, at the age of 88, having won 5 parliamentary elections, and having spent 14 years as Prime Minister, 10 years as President of the Republic, and a total of more than sixty years in active politics. For his long service to democracy and as a pioneer of European integration from the earliest stages of the European Union, Karamanlis was awarded one of the most prestigious European prizes, the Karlspreis, in 1978. He bequeathed his archives to the Konstantinos Karamanlis Foundation, a conservative think tank he had founded and endowed.

Karamanlis died after a short illness in 1998, at the age of 91.

His nephew Kostas Karamanlis later became the leader of the New Democracy party (Nea Demokratia) and Prime Minister of Greece from 2004 to 2009.

Karamanlis has been praised for presiding over an early period of fast economic growth for Greece (1955 – 63) and for being the primary engineer of Greece's successful bid for membership in the European Union.

His supporters came to laud him as the charismatic Ethnarches (National Leader). Some of his left wing opponents have accused him of condoning rightist "para - statal" groups, whose members undertook Via kai Notheia (Violence and Corruption), i.e., fraud during the electoral contests between ERE and Papandreou's Center Union party, and were responsible for the assassination of Gregoris Lambrakis. Some of Karmanlis's conservative opponents have criticized his socialist economic policies during the 1970s, which included the nationalization of Olympic Airways and Emporiki Bank and the creation of a large public sector. Karamanlis has also been criticized by Ange S. Vlachos for indecisiveness in his management of the Cyprus crisis in 1974 even though it is widely acknowledged that he skillfully avoided an all out war with Turkey during that time.

Karamanlis is acknowledged for his successful restoration of Democracy during metapolitefsi and the repair of the two great national schisms by first legalizing the communist party and by establishing the system of presidential democracy in Greece. His successful prosecution of the junta during the junta trials and the heavy sentences imposed on the junta principals also sent a message to the army that the era of immunity from constitutional transgressions by the military was over. Karamanlis' policy of European integration is also acknowledged to have ended the paternalistic relation between Greece and the United States.

On 29 June 2005 an audio - visual tribute celebrating Konstantinos Karamanlis' contribution to Greek culture took place at the Odeon of Herodes Atticus. George Remoundos was the stage director and Stavros Xarhakos conducted and selected the music. The event under the title of Cultural Memories was organized by the Konstantinos G. Karamanlis Foundation. In 2007 several events were held to celebrate 100 years since his birth.

Andreas G. Papandreou (Greek: Ανδρέας Γ. Παπανδρέου) (5 February 1919 – 23 June 1996) was a Greek economist, a socialist politician and a dominant figure in Greek politics. The son of Georgios Papandreou, Andreas was a Harvard trained academic. He served two terms as Prime Minister of Greece (21 October 1981, to 2 July 1989, and 13 October 1993, to 22 January 1996).

His assumption of power in 1981 influenced

the course of Greek political history, ending an almost 50 year long

system of power dominated by conservative forces; the achievements of

his successive governments include the official recognition of the Greek Resistance against the Axis, the establishment of the National Health System and the Supreme Council for Personnel Selection (ASEP),

the passage of Law 1264 / 1982 which secured the right to strike and

greatly improved the rights of workers, the constitutional amendment of

1985 – 1986 which strengthened parliamentarism and reduced the powers of the unelected President, the conduct of an assertive and independent Greek foreign policy, the expansion in the power of local governments, many progressive reforms in Greek Law, and granting permission to the refugees of the Greek Civil War to return home in Greece. The Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK)

which he founded and led, was the first non - communist political party

in Greek history with a mass based organization, and introduced an

unprecedented level of political and social participation in Greek

society. In a poll conducted by Kathimerini in 2007, 48% of those polled called Papandreou the "most important Greek Prime Minister". In the same poll, the first four years of Papandreou's government after Metapolitefsi were voted as the best government Greece ever had.

Papandreou was born on the island of Chios, Greece, the son of the leading Greek liberal politician George Papandreou. His mother, born Zofia (Sofia) Mineyko, was half Polish. Before university, he attended Athens College a leading private school in Greece. He attended the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens from 1937 till 1938 when, during the Fascist Metaxas dictatorship, he was arrested for purported Trotskyism. Following representations by his father, he was allowed to leave for the US.

In 1943, Papandreou received a PhD in Economics from Harvard University. Immediately after getting his PhD, Papandreou joined America's war effort and volunteered for the US Navy where he served as a hospital corpsman at the Bethesda Naval Hospital for war wounded, and

became a United States citizen. He returned to Harvard in 1946 and

served as a lecturer and associate professor until 1947. He then held

professorships at the University of Minnesota, Northwestern University, the University of California, Berkeley (where he was chair of the Department of Economics), Stockholm University and York University in Toronto. In 1948, he entered into a relationship with University of Minnesota journalism student Margaret Chant. After

Chant obtained a divorce and after his own divorce from Christina

Rasia, his first wife, Papandreou and Chant were married in 1951. They

had three sons and a daughter. Papandreou also had with Swedish actress and TV presenter Ragna Nyblom a daughter out of wedlock, Emilia Nyblom, who was born in 1969 in Sweden.

Papandreou returned to Greece in 1959, where he headed an economic development research program, by invitation of Prime Minister Konstantinos Karamanlis. In 1960, he was appointed Chairman of the Board of Directors and General Director of the Athens Economic Research Center, and Advisor to the Bank of Greece. In 1963, his father George Papandreou, head of the Center Union, became Prime Minister of Greece. Andreas became his chief economic advisor. He renounced his American citizenship and was elected to the Greek Parliament in the Greek legislative election, 1964. He immediately became Minister to the First Ministry of State (in effect, assistant Prime Minister).

Papandreou took publicly a neutral stand on the Cold War and wished for Greece to be more independent from the United States. He also criticized the massive presence of American military and intelligence in Greece, and sought to remove senior officers with anti - democratic tendencies from the Greek military.

In 1965, while the "Aspida" conspiracy within the Hellenic Army, alleged by the political opposition to involve Andreas personally, was being investigated, George Papandreou moved to fire the defense minister and assume the post himself. Constantine II of Greece refused to endorse this move and essentially forced George Papandreou's resignation. Greece entered a period of political polarization and instability, which ended with the coup d'état of 21 April 1967.

When the Greek Colonels led by Georgios Papadopoulos seized power in April 1967, Andreas was incarcerated while his father George Papandreou was put under house arrest. George Papandreou, already at advanced age, died in 1968. Under heavy pressure from American academics and intellectuals, such as John Kenneth Galbraith, a friend of Andreas since their Harvard days, the military regime released Andreas on condition that he leave the country. Papandreou then moved to Sweden with his wife, four children, and mother. There he accepted a post at Stockholm University. In Paris, while in exile, Andreas Papandreou formed an anti - dictatorship organization, the Panhellenic Liberation Movement (PAK), and toured the world rallying opposition to the Greek military regime. Despite his former American citizenship and academic career in the United States, Papandreou held the Central Intelligence Agency responsible for the 1967 coup and became increasingly critical of the Federal government of the United States.

In the early 1970s, during the latter phase of the dictatorship in Greece, Papandreou, along with most leading Greek politicians, in exile or in Greece, opposed the process of political normalization attempted by Georgios Papadopoulos and his appointed PM, Spyros Markezinis. On 6 August 1974, Andreas Papandreou called an extraordinary meeting of the National Congress of PAK in Winterthur, Switzerland, which decided its dissolution without announcing it publicly.

Papandreou returned to Greece after the fall of the junta in 1974, during metapolitefsi, and formed a new "radical" party, the Panhellenic Socialist Movement, or PASOK. Most of his former PAK companions, as well as members of other anti - dictatorial groups such as the Democratic Defense joined in the new party. He also testified in the first of the Greek Junta Trials about the alleged involvement of the junta with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

In the Greek legislative election, 1974, PASOK received only 13.5% of the vote, but in 1977 it polled 25%, and Papandreou became Leader of the Opposition. At the Greek legislative election, 1981, PASOK won a landslide victory over the conservative New Democracy Party, and Papandreou became Greece's first socialist Prime Minister.

In office, Papandreou backtracked from much of his campaign rhetoric and followed a more conventional approach. Greece did not withdraw from NATO, United States troops and military bases were not ordered out of Greece, and Greek membership in the European Economic Community continued, largely because Papandreou proved very capable of securing monetary aid for Greece. In domestic affairs, Papandreou's government immediately carried out a massive program of wealth redistribution upon coming into office that immediately increased the prosperity of the common people. Pensions, together with average wages and the minimum wage, were increased in real terms, and changes were made to labor laws which up until 1984 made it difficult for employers to make workers redundant. The impact of the PASOK Government’s social and economic policies was such that it was estimated in 1988 that two thirds of the decrease in inequality that occurred in Greece between 1974 and 1982 took place between 1981 and 1982.

During its time in office, Papandreou's government carried through sweeping reforms of social policy by introducing a welfare state, significantly expanding welfare measures, expanding health care coverage (the "National Health System" was instituted, which made modern medical procedures available in rural areas for the first time) promoting state subsidized tourism for lower income families, index linking pensions, and funding social establishments for the elderly. Rural areas benefited from improved state services, the rights and income of low paid workers were considerably improved, and refugees from the Civil War living in exile from persecution were allowed to return with impunity.

A more progressive taxation scheme was introduced and budgetary support for artistic and cultural programs was increased. The government also introduced a wage indexation system which helped to close the gap modestly between the highest and lowest paid workers, while the share of GNP devoted to social welfare, social insurance, and health was significantly increased.

As part of Papandreou’s "Contract with the People," new liberalizing laws were introduced which decriminalized adultery, abolished (in theory) the dowry system, eased the process for obtaining a divorce, and enhanced the legal status of women. In 1984, for instance, women were guaranteed equal pay for equal work. Papandreou also introduced various reforms in the administration and curriculum of the Greek educational system, allowing students to participate in the election process for their professors and deans in the university, and abolishing tenure.

In a move strongly opposed by the Church of Greece, Papandreou introduced, for the first time in Greece, the process of civil marriage. Prior to the institution of civil marriages in Greece, the only legally recognized marriages were those conducted in the Church of Greece. Couples seeking a civil marriage had to get married outside Greece, generally in Italy. Also, under PASOK, the Greek State also appropriated real estate properties previously owned by the Church.

A major part of Papandreou's allagi (change) involved driving out the "old families" ("tzakia" literally: fireplaces using

the traditional Greek expression for the genealogy of families), which

dominated Greek politics and economy and belonged to the traditional

Greek Right.

Papandreou was comfortably re-elected in the Greek legislative election, 1985 with 46% of the vote, and won still further popularity in March 1987 by his strong leadership during a Greek - Turkish crisis in the Aegean Sea, but from the summer of 1988, his premiership became increasingly clouded by controversy, as the Bank of Crete scandal exploded. In 1989, he divorced his wife Margaret Papandreou and married Dimitra Liani, while in the same year he was indicted by the Hellenic Parliament in connection with a US $200 million Bank of Crete embezzlement scandal, and was accused of facilitating the embezzlement by ordering state corporations to transfer their holdings to the Bank of Crete, where the interest was allegedly skimmed off to benefit PASOK, and possibly some of its highest functionaries.

Following the many repercussions of the so-called Koskotas scandal, the Greek legislative election, June 1989 elections produced a deadlock, leading to a prolonged political crisis. In the subsequent Greek legislative election, November 1989 Papandreou's PASOK's won 40% of the popular vote, compared to the rival New Democracy's 46%, and, due to changes made in electoral law one year before the elections by the then reigning PASOK administration, New Democracy was not able to form a government. The Greek legislative election, 1990 followed.

In the wake of three consecutive elections between 1989 and 1990, the New Democracy leader, Constantine Mitsotakis, eventually received sufficient support to form a government. In January 1992, Papandreou himself was cleared of any wrongdoing in the Koskotas scandal after a 7–6 vote in the specially convened High Court trial, ordered by the Hellenic Parliament, with the support of both main parties, New Democracy and PASOK.

Papandreou confounded his critics by winning the Greek legislative election, 1993, and returned to power; however, his fragile health kept him from exercising firm political leadership. He was hospitalized with advanced heart disease and renal failure on 21 November 1995 and finally retired from office on 16 January 1996. He died on 23 June 1996, with his funeral procession producing crowds, ranging from "hundreds of thousands" to "millions" to bid farewell to Andreas. In 1999, Papandreou was posthumously awarded the Swedish Order of the Polar Star.

The

expenditure program of the Papandreou government during 1981 – 1990 has

been described as excessive by its conservative critics. The excessive expenditures were not accompanied by corresponding revenue increases and this led to increases in budget deficits and the public debt. Many economic indicators worsened during 1981 – 1990 and the economic policies of his government were condemned as a failure by his critics. On

the other hand, according to his supporters they were very successful,

drastically increasing the purchasing power of the vast majority of

Greeks, with personal incomes growing by 26% in real terms during the

course of the Eighties. Papandreou's

increased spending in his early years in power (1981 – 1985) was

necessary in order to heal the deep wounds of the Greek society, a

society that was still deeply divided by the brutal memories of the

Civil War and the right wing repression that followed; furthermore,

the postwar government philosophy of the Greek conservatives simply saw

the state as a tool of repression, with very little money spent on

health and education, and little interest on the well being of society.

Papandreou was praised for conducting an independent and multidimensional foreign policy, and proved to be a master of the diplomatic game, thus increasing the importance of Greece in the international system; he was co-creator in 1982 and subsequently an active participant in a movement promoted by the Parliamentarians for Global Action, the Initiative of the Six, which included, besides the Greek PM, Mexico's president Miguel de la Madrid, Argentina's President Raúl Alfonsín, Sweden's PM Olof Palme, Tanzania's president Julius Nyerere and India's Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. The movement's stated objective was the "promotion of peace and progress for all mankind". After various initiatives, mostly directed at pressuring the United States and the Soviet Union to stop nuclear testing and reduce the level of nuclear arms, it eventually disbanded.

Papandreou's rhetoric was at times antagonistic to the United States. He was the first western prime minister to visit General Wojciech Jaruzelski in Poland. According to the Foreign Affairs magazine Papandreou went on record as saying that since the USSR is not a capitalist country "one cannot label it an imperialist power." According to Papandreou, "the Soviet Union represent[ed] a factor that restrict[ed] the expansion of capitalism and its imperialistic aims". This antagonistic stance made him extremely popular, because the previous conservative governments were seen by the Greek people as slavishly loyal to US interests.

Papandreou's government was the first in post war Greece that redirected the nation's defense policy to suit its own security needs, and not those of the United States. From 1947 until 1981, the US had more influence in Greece's military policy than the indigenous Greek high command.

Papandreou supported the causes of various national liberation movements in the world, and agreed for Greece to host representatives offices of many such organizations. He supported the cause of Palestinian liberation, met repeatedly with PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat and condemned Israeli policies in the occupied territories.

Among

both his supporters and his opponents, Papandreou was referred to

simply by his first name, "Andreas", a unique situation in Greek political history, and a testament to his charisma and popularity. Andreas was also famous for wearing his business suits with turtleneck sweaters (Ζιβάγκο in Greek),

instead of the traditional white shirt and tie; he thus created a huge

fashion, mainly but not exclusively among his political supporters. His

first appearance in the Greek Parliament with a black turtleneck instead

of shirt and tie caused a massive uproar in the conservative press, who

considered him disrespectful of Parliament; however, the whole issue

only added to his popularity.

Papandreou exercised a more independent foreign policy elevating Greece's profile among non - aligned nations. He affirmed Greece's independence in setting her own policy agenda, both internally and externally, free from any foreign domination.

His opponents on the left, on the other hand, including the KKE, accused him of supporting, in practice, the agenda of NATO and the United States.

Andreas Papandreou is widely acknowledged as having shifted political power from the traditional conservative Greek Right, which had dominated Greek politics for decades, to a more populist and center left locus. Political forces which remained the so-called pariahs in politics as of the end of the Greek Civil War, were given a chance to prove themselves in democratically elected governments. This shift in the Greek political landscape helped heal some of the old civil war wounds; Greece became more pluralistic, and more in line with the political system of other western European countries. Papandreou also systematically pursued inclusionist politics which ended the sociopolitical and economic exclusion of many social classes in the post civil war era.

It is also acknowledged that Papandreou, along with Karamanlis, played a leading role in establishing Democracy in Greece during metapolitefsi. He is described as both prudent and a realist, despite his appearance as a leftist ideologue and charismatic orator. His choices to remain in the European Union and NATO, both of which he vehemently opposed for many years, proved his pragmatical approach. Even his approach of negotiating the removal of the US bases from Greece was diplomatic, because although it was agreed to remove them, some of the bases remained. His skillful handling of these difficult policies had the effect of providing common policy goals to the political forces of Greece. Complementing this political realism, Andreas' ability to publicly say no to the Americans gave Greeks a sense of national independence and psychological self worth. Perhaps his most important achievement was the establishment of political equality among Greeks; during his years in power the defeated left wingers of the Civil War were no longer treated like second class citizens and a vital part of national memory was reclaimed.

Papandreou's successor in office, Costas Simitis, broke with a number of Papandreou's approaches.

Papandreou's son, George Papandreou, was elected leader of PASOK in February 2004 and Prime Minister during the October 2009 general elections. A common slogan among PASOK followers in political rallies, invokes Andreas' legacy with the chant "Andrea, zis! Esi mas odigis!" ("Andreas, you are still alive! You're leading us!").

In two separate polls, conducted in 2007 and 2010, Andreas Papandreou was voted as the best Prime Minister of Greece since the restoration of democracy in 1974.