<Back to Index>

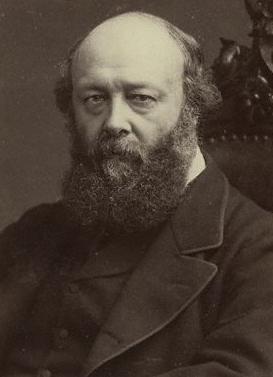

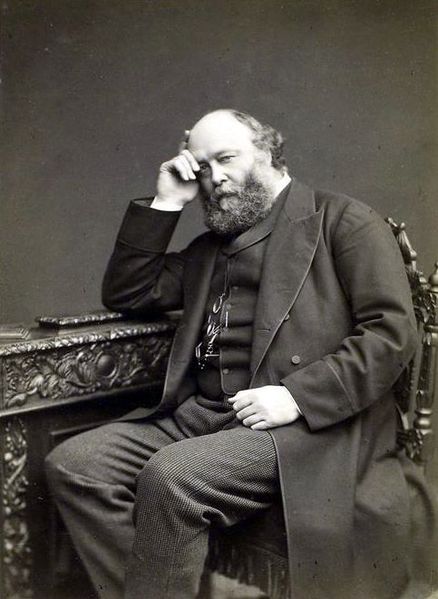

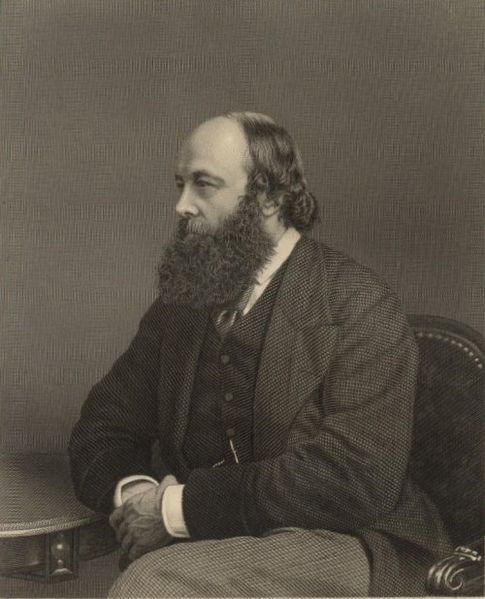

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne - Cecil, 1830

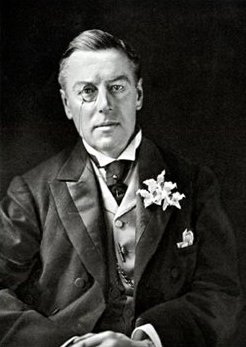

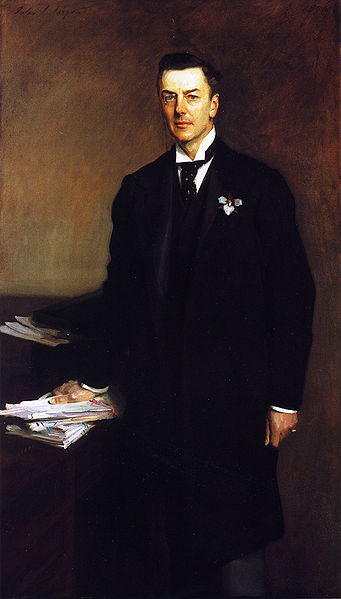

- Secretary of State for the Colonies Joseph Chamberlain, 1836

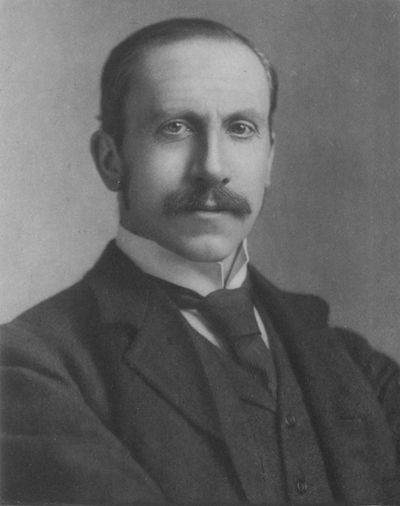

- Governor of the Cape Colony Alfred Milner, 1854

PAGE SPONSOR

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne - Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, KG, GCVO, PC (3 February 1830 – 22 August 1903), styled Lord Robert Cecil before 1865 and Viscount Cranborne from June 1865 until April 1868, was a British Conservative statesman and thrice Prime Minister, serving for a total of over 13 years. He was the first British Prime Minister of the 20th century and the last Prime Minister to head his full administration from the House of Lords.

Lord Robert Cecil was first elected to the House of Commons in 1854 and served as Secretary of State for India in Lord Derby's Conservative government from 1866 until his resignation in 1867 over its introduction of Benjamin Disraeli's Reform Bill that

extended the suffrage to working class men. In 1868 upon the death of

his father, Cecil was elevated to the House of Lords. In 1874 when

Disraeli formed an administration Salisbury returned as Secretary of

State for India and in 1878 was appointed Foreign Secretary and played a

leading part in the Congress of Berlin, despite doubts over Disraeli's pro-Ottoman policy. After the Conservatives lost the 1880 election and Disraeli's death the year after, Salisbury emerged as Conservative leader in the House of Lords, with Sir Stafford Northcote leading the party in the Commons. He became Prime Minister in June 1885 when the Liberal leader William Ewart Gladstone resigned, and he held the office until January 1886. When Gladstone came out in favour of Home Rule for Ireland, Salisbury opposed him and formed an alliance with the breakaway Liberal Unionists and they won the subsequent general election.

He remained Prime Minister until Gladstone's Liberals formed a

government with the support of the Irish Nationalist Party, despite the

Unionists gaining the largest number of votes and seats in the 1892 general election. However the Liberals lost the 1895 general election and Salisbury once again became Prime Minister, leading Britain to war against the Boers and the Unionists to another electoral victory in 1900 before relinquishing the premiership to his nephew Arthur Balfour. He died a year later in 1903.

Lord Robert Cecil was the second son of the 2nd Marquess of Salisbury. In 1840 he went to Eton College, where he did well in French, German, the classics and theology. However he left in 1845 due to intense bullying. In December 1847 he went to Christ Church, Oxford, although he received an honorary fourth class in mathematics conferred by nobleman's privilege due to ill health. Whilst at Oxford he associated himself with the Tractarian movement.

In April 1850 he joined Lincoln's Inn but subsequently did not enjoy law. His doctor advised him to travel for his health and so in July 1851 to May 1853 Cecil travelled through Cape Colony, Australia, Tasmania and New Zealand. He

disliked the Boers and wrote that free institutions and self - government

could not be granted to the Cape Colony because the Boers outnumbered

the British three - to - one and "it will simply be delivering us over bound

hand and foot into the power of the Dutch, who hate us as much as a

conquered people can hate their conquerors". He found the Kaffirs "a

fine set of men – whose language bears traces of a very high former

civilisation", similar to Italian. They were "an intellectual race, with

great firmness and fixedness of will" but "horribly immoral" as they

lacked theism. In the Bendigo gold mine

of Australia he claimed that "there is not half as much crime or

insubordination as there would be in an English town of the same wealth

and population". 10,000 miners were policed by four men armed with

carbines and at Mount Alexander 30,000

people were protected by 200 policemen, with over 30,000 ounces of gold

mined per week. He believed that there was "generally far more civility

than I should be likely to find in the good town of Hatfield" and

claimed this was due to "the government was that of the Queen, not of

the mob; from above, not from below. Holding from a supposed right

(whether real or not, no matter)" and from "the People the source of all

legitimate power". Cecil said of the Maori of

New Zealand: "The natives seem when they have converted to make much

better Christians than the white man". A Maori chief offered Cecil five

acres near Auckland, which he declined.

He entered the House of Commons as a Conservative in 1853, as MP for Stamford in Lincolnshire. He retained this seat until entering the peerage and it was not contested during his time as its representative. In his election address he opposed secular education and "ultramontane" interference with the Church of England which was "at variance with the fundamental principles of our constitution". He would oppose "any such tampering with our representative system as shall disturb the reciprocal powers on which the stability of our constitution rests". In 1867, after his brother Eustace complained of being addressed by constituents in a hotel, Cecil responded: "A hotel infested by influential constituents is worse than one infested by bugs. It's a pity you can't carry around a powder insecticide to get rid of vermin of that kind".

In December 1856 Cecil began publishing articles for the Saturday Review, which he contributed anonymously for the next nine years. From 1861 to 1864 he published 422 articles in it, in total the weekly published 608 of his articles. The Quarterly Review was the foremost intellectual journal of the age and of the twenty - six issues published between spring 1860 and summer 1866, Cecil had anonymous articles in all but three of them. He also wrote lead articles for the Tory daily newspaper the Standard. In 1859 Cecil was a founding co-editor of Bentley's Quarterly Review, with J.D. Cook and Rev. William Scott, but this closed after four issues.

Salisbury criticised the foreign policy of Lord John Russell,

claiming he was "always being willing to sacrifice anything for

peace... colleagues, principles, pledges... a portentous mixture of

bounce and baseness... dauntless to the weak, timid and cringing to the

strong". The lessons to be learnt from Russell's foreign policy,

Salisbury believed, were that he should not listen to the Opposition of

the press otherwise "we are to be governed… by a set of weathercocks,

delicately poised, warranted to indicate with unnerving accuracy every

variation in public feeling". Secondly: "No one dreams of conducting

national affairs with the principles which are prescribed to

individuals. The meek and poor - spirited among nations are not to be

blessed, and the common sense of Christendom has always prescribed for

national policy principles diametrically opposed to those that are laid

down in the Sermon on the Mount".

Thirdly: "The assemblies that meet in Westminster have no jurisdiction

over the affairs of other nations. Neither they nor the Executive,

except in plain defiance of international law, can interfere [in the

internal affairs of other countries]... It is not a dignified position

for a Great Power to occupy, to be pointed out as the busybody of

Christendom". Finally, Britain should not threaten other countries

unless prepared to back this up by force: "A willingness to fight is the point d'appui of

diplomacy, just as much as a readiness to go to court is the starting

point of a lawyer’s letter. It is merely courting dishonour, and

inviting humiliation for the men of peace to use the habitual language

of the men of war".

In 1866 Lord Robert, now Viscount Cranborne after the death of his older brother, Cranborne entered the third government of Lord Derby as Secretary of State for India.

When in 1867 John Stuart Mill proposed a type of proportional representation, Cranborne argued that: "It was not of our atmosphere — it was not in accordance with our habits; it did not belong to us. They all knew that it could not pass. Whether that was creditable to the House or not was a question into which he would not inquire; but every Member of the House the moment he saw the scheme upon the Paper saw that it belonged to the class of impracticable things".

On 2 August when the Commons debated the Orissa famine in India, Cranborne spoke out against experts, political economy, and the government of Bengal. Utilising the Blue Books, Cranborne criticised officials for "walking in a dream… in superb unconsciousness, believing that what had been must be, and that as long as they did nothing absolutely wrong, and they did not displease their immediate superiors, they had fulfilled all the duties of their station". These officials worshipped political economy "as a sort of "fetish"... [they] seemed to have forgotten utterly that human life was short, and that man did not subsist without food beyond a few days". Three quarters of a million people had died because officials had chosen "to run the risk of losing the lives than to run the risk of wasting the money". Cranborne's speech was received with "an enthusiastic, hearty cheer from both sides of the House" and Mill crossed the floor of the Commons to congratulate him on it. The famine left Cranborne with a lifelong suspicion of experts and in the photograph albums at his home covering the years 1866 – 67 there are two images of skeletal Indian children amongst the family pictures.

When

parliamentary reform came to prominence again in the mid 1860s,

Cranborne worked hard to master electoral statistics until he became an

expert. When the Liberal Reform Bill was being debated in 1866,

Cranborne studied the census returns to see how each clause in the Bill

would affect the electoral prospects in each seat. Cranborne

did not expect Disraeli's conversion to reform, however. When the

Cabinet met on 16 February 1867, Disraeli voiced his support for some

extension of the suffrage, providing statistics amassed by Robert Dudley Baxter,

showing that 330,000 people would be given the vote and all except

60,000 would be granted extra votes. Cranborne studied Baxter's

statistics and on 21 February he met Lord Carnarvon,

who wrote in his diary: "He is firmly convinced now that Disraeli has

played us false, that he is attempting to hustle us into his measure,

that Lord Derby is in his hands and that the present form which the

question has now assumed has been long planned by him". They agreed to

"a sort of offensive and defensive alliance on this question in the

Cabinet" to "prevent the Cabinet adopting any very fatal course".

Disraeli had "separate and confidential conversations... carried on with

each member of the Cabinet from whom he anticipated opposition [which]

had divided them and lulled their suspicions". That

same night Cranborne spent three hours studying Baxter's statistics and

wrote to Carnarvon the day after that although Baxter was right overall

in claiming that 30% of £10 ratepayers who qualified for the vote

would not register, it would be untrue in relation to the smaller

boroughs where the register is kept up to date. Cranborne also wrote to

Derby arguing that he should adopt 10 shillings rather than Disraeli's

20 shillings for the qualification of the payers of direct taxation:

"Now above 10 shillings you won't get in the large mass of the £20

householders. At 20 shillings I fear you won't get more than 150,000

double voters, instead of the 270,000 on which we counted. And I fear

this will tell horribly on the small and middle - sized boroughs".

On 23 February Cranborne protested in Cabinet and the next day analysed Baxter's figures using census returns and other statistics to determine how Disraeli's planned extension of the franchise would affect subsequent elections. Cranborne found that Baxter had not taken into account the different types of boroughs in the totals of new voters. In small boroughs under 20,000 the "fancy franchises" for direct taxpayers and dual voters would be less than the new working - class voters in each seat. The same day he met Carnarvon and they both studied the figures, coming to the same result each time: "A complete revolution would be effected in the boroughs" due to the new majority of the working - class electorate. Cranborne wanted to send his resignation to Derby along with the statistics but Cranborne agreed to Carnarvon's suggestion that as a Cabinet member he had a right to call a Cabinet meeting. It was planned for the next day, 25 February. Cranborne wrote to Derby that he had discovered that Disraeli's plan would "throw the small boroughs almost, and many of them entirely, into the hands of the voter whose qualification is less than £10. I do not think that such a proceeding is for the interest of the country. I am sure that it is not in accordance with the hopes which those of us who took an active part in resisting Mr Gladstone's Bill last year in those whom we induced to vote for us". The Conservative boroughs with populations less than 25,000 (a majority of the boroughs in Parliament) would be very much worse off under Disraeli's scheme than the Liberal Reform Bill of the previous year: "But if I assented to this scheme, now that I know what its effect will be, I could not look in the face those whom last year I urged to resist Mr Gladstone. I am convinced that it will, if passed, be the ruin of the Conservative party".

When Cranborne entered the Cabinet meeting on 25 February "with reams of paper in his hands" he begun by reading statistics but was interrupted to be told of the proposal by Lord Stanley that they should agree to a £6 borough rating franchise instead of the full household suffrage, and a £20 county franchise rather than £50. The Cabinet agreed to Stanley's proposal. The meeting was so contentious that a minister who was late initially thought they were debating the suspension of habeas corpus. The next day another Cabinet meeting took place, with Cranborne saying little and the Cabinet adopting Disraeli's proposal to bring in a Bill in a week's time. On 28 February a meeting of the Carlton Club took place, with a majority of the 150 Conservative MPs present supporting Derby and Disraeli. At the Cabinet meeting on 2 March, Cranborne, Carnarvon and General Peel were pleaded with for two hours to not resign but when Cranborne "announced his intention of resigning... Peel and Carnarvon, with evident reluctance, followed his example". John Manners observed that Cranborne "remained unmoveable". Derby closed his red box with a sigh and stood up, saying "The Party is ruined!" Cranborne got up at the same time, with Peel remarking: "Lord Cranborne, do you hear what Lord Derby says?" Cranborne ignored this and the three resigning ministers left the room. Cranborne's resignation speech was met with loud cheers and Carnarvon observed that it was "moderate and in good taste – a sufficient justification for us who seceded and yet no disclosure of the frequent changes in policy in the Cabinet".

Disraeli introduced his Bill on 18 March and it would extend the suffrage to all rate - paying householders of two years' residence, dual voting for graduates or those of a learned profession, or those with £50 in governments funds or in the Bank of England or a savings bank. These "fancy franchises", as Cranborne had foreseen, did not survive the Bill's course through Parliament; dual voting was dropped in March, the compound householder vote in April; and the residential qualification was reduced in May. In the end the county franchise was granted to householders rated at £12 annually. On 15 July the third reading of the Bill took place and Cranborne spoke first, in a speech which his biographer Andrew Roberts has called "possibly the greatest oration of a career full of powerful parliamentary speeches". Cranborne observed how the Bill "bristled with precautions, guarantees and securities" had been stripped of these. He attacked Disraeli by pointing out how he had campaigned against the Liberal Bill in 1866 yet the next year introduced a Bill more extensive than the one rejected. In the peroration Cranborne said:

I desire to protest, in the most earnest language which I am capable of using, against the political morality on which the manoeuvres of this year have been based. If you borrow your political ethics from the ethics of the political adventurer, you may depend upon it the whole of your representative institutions will crumble beneath your feet. It is only because of that mutual trust in each other by which we ought to be animated, it is only because we believe that expressions and convictions expressed, and promises made, will be followed by deeds, that we are enabled to carry on this party Government which has led this country to so high a pitch of greatness. I entreat honourable Gentlemen opposite not to believe that my feelings on this subject are dictated simply by my hostility on this particular measure, though I object to its most strongly, as the House is aware. But, even if I took a contrary view – if I deemed it to be most advantageous, I still should deeply regret that the position of the Executive should have been so degraded as it has been in the present session: I should deeply regret to find that the House of Commons has applauded a policy of legerdemain; and I should, above all things, regret that this great gift to the people – if gift you think – should have been purchased at the cost of a political betrayal which has no parallel in our Parliamentary annals, which strikes at the root of all that mutual confidence which is the very soul of our party Government, and on which only the strength and freedom of our representative institutions can be sustained.

In his article for the October Quarterly Review, entitled ‘The Conservative Surrender’, Cranborne criticised Derby because he had "obtained the votes which placed him in office on the faith of opinions which, to keep office, he immediately repudiated... He made up his mind to desert these opinions at the very moment he was being raised to power as their champion". Also, the annals of modern parliamentary history could find no parallel for Disraeli's betrayal; historians would have to look "to the days when Sunderland directed the Council, and accepted the favours of James when he was negotiating the invasion of William". Disraeli responded in a speech that Cranborne was "a very clever man who has made a very great mistake".

In 1868, on the death of his father, he inherited the Marquessate of Salisbury, thereby becoming a member of the House of Lords. From 1868 and 1871, he was chairman of the Great Eastern Railway, which was then experiencing losses. During his tenure, the company was taken out of chancery, and paid out a small dividend on its ordinary shares.

He returned to government in 1874, serving once again as India Secretary in the government of Benjamin Disraeli, and Britain's Ambassador Plenipotentiary at the 1876 Constantinople Conference. Salisbury gradually developed a good relationship with Disraeli, whom he had previously disliked and mistrusted.

During a Cabinet meeting on 7 March 1878, a discussion arose over whether to occupy Mytilene. Lord Derby recorded in his diary that "Of all present Salisbury by far the most eager for action: he talked of our sliding into a position of contempt: of our being humiliated etc." At the Cabinet meeting the next day, Derby recorded that John Manners objected to occupying the city "on the ground of right. Salisbury treated scruples of this kind with marked contempt, saying, truly enough, that if our ancestors had cared for the rights of other people, the British empire would not have been made. He was more vehement than any one for going on. In the end the project was dropped..."

In 1878, Salisbury succeeded Lord Derby (son of the former Prime Minister) as Foreign Secretary in time to help lead Britain to "peace with honour" at the Congress of Berlin. For this he was rewarded with the Order of the Garter.

Following

Disraeli's death in 1881, the Conservatives entered a period of

turmoil. Salisbury became the leader of the Conservative members of the

House of Lords, though the overall leadership of the party was not

formally allocated. So he struggled with the Commons leader Sir Stafford Northcote, a struggle in which Salisbury eventually emerged as the leading figure.

In 1884 Gladstone introduced a Reform Bill which would extend the suffrage to two million rural workers. Salisbury and Northcote agreed that any Reform Bill would be supported only if a parallel redistributionary measure was introduced as well. In a speech in the Lords, Salisbury claimed: "Now that the people have in no real sense been consulted, when they had, at the last General Election, no notion of what was coming upon them, I feel that we are bound, as guardians of their interests, to call upon the government to appeal to the people, and by the result of that appeal we will abide". The Lords rejected the Bill and Parliament was prorogued for ten weeks. Writing to Canon Malcolm MacColl, Salisbury believed that Gladstone's proposals for reform without redistribution would mean "the absolute effacement of the Conservative Party. It would not have reappeared as a political force for thirty years. This conviction... greatly simplified for me the computation of risks". At a meeting of the Carlton Club on 15 July, Salisbury announced his plan for making the government introduce a Seats (or Redistribution) Bill in the Commons whilst at the same time delaying a Franchise Bill in the Lords. The unspoken implication being that Salisbury would relinquish the party leadership if his plan was not supported. Although there was some dissent, Salisbury carried the party with him.

Salisbury wrote to Lady John Manners on 14 June that he did not regard female suffrage as a question of high importance "but when I am told that my ploughmen are capable citizens, it seems to me ridiculous to say that educated women are not just as capable. A good deal of the political battle of the future will be a conflict between religion and unbelief: & the women will in that controversy be on the right side".

On 21 July a large meeting for reform was held at Hyde Park. Salisbury said in The Times that "the employment of mobs as an instrument of public policy is likely to prove a sinister precedent". On 23 July at Sheffield, Salisbury said that the government "imagine that thirty thousand Radicals going to amuse themselves in London on a given day expresses the public opinion of the day... they appeal to the streets, they attempt legislation by picnic". Salisbury further claimed that Gladstone adopted reform as a "cry" to deflect attention from his foreign and economic policies at the next election. He claimed that the House of Lords was protecting the British constitution: "I do not care whether it is an hereditary chamber or any other – to see that the representative chamber does not alter the tenure of its own power so as to give a perpetual lease of that power to the party in predominance at the moment". On 25 July at a reform meeting in Leicester consisting of 40,000 people, Salisbury was burnt in effigy and a banner quoted Shakespeare's Henry VI: "Old Salisbury – shame to thy silver hair, Thou mad misleader". On 9 August in Manchester over 100,000 came to hear Salisbury speak. On 30 September at Glasgow he said: "We wish that the franchise should pass but that before you make new voters you should determine the constitution in which they are to vote". Salisbury published an article in the National Review for October, titled ‘The Value of Redistribution: A Note on Electoral Statistics’. He claimed that the Conservatives "have no cause, for Party reasons, to dread enfranchisement coupled with a fair redistribution". Judging by the 1880 results, Salisbury asserted that the overall loss to the Conservatives of enfranchisement without redistribution would be 47 seats. Salisbury spoke throughout Scotland and claimed that the government had no mandate for reform when it had not appealed to the people.

Gladstone offered wavering Conservatives a compromise a little short of enfranchisement and redistribution, and after the Queen unsuccessfully attempted to persuade Salisbury to compromise, he wrote to Rev. James Baker on 30 October: "Politics stand alone among human pursuits in this characteristic, that no one is conscious of liking them – and no one is able to leave them. But whatever affection they may have had they are rapidly losing. The difference between now and thirty years ago when I entered the House of Commons is inconceivable". On 11 November the Franchise Bill received its third reading in the Commons and it was due to get a second reading in the Lords. The day after at a meeting of Conservative leaders, Salisbury was outnumbered in his opposition to compromise. On 13 February Salisbury rejected MacColl's idea that he should meet Gladstone, as he believed the meeting would be found out and that Gladstone had no genuine desire to negotiate. On 17 November it was reported in the newspapers that if the Conservatives gave "adequate assurance" that the Franchise Bill would pass the Lords before Christmas the government would ensure that a parallel Seats Bill would receive its second reading in the Commons as the Franchise Bill went into committee stage in the Lords. Salisbury responded by agreeing only if the Franchise Bill came second. The Carlton Club met to discuss the situation, with Salisbury's daughter writing:

The three arch - funkers Cairns, Richmond and Carnarvon cried out declaring that he would accept no compromise at all as it was absurd to imagine the Government conceding it. When the discussion was at its height (very high) enter Arthur [Balfour] with explicit declamation dictated by G.O.M. in Hartington's handwriting yielding the point entirely. Tableau and triumph along the line for the ‘stiff’ policy which had obtained terms which the funkers had not dared hope for. My father's prevailing sentiment is one of complete wonder... we have got all and more than we demanded.

Despite

the controversy which had raged, the meetings of leading Liberals and

Conservatives on reform at Downing Street were amicable. Salisbury and

the Liberal Sir Charles Dilke dominated

discussions as they had both closely studied in detail the effects of

reform on the constituencies. After one of the last meetings on 26

November, Gladstone told his secretary that "Lord Salisbury, who seems

to monopolize all the say on his side, has no respect for tradition. As

compared with him, Mr Gladstone declares he is himself quite a

Conservative. They got rid of the boundary question, minority

representation, grouping and the Irish difficulty. The question was

reduced to... for or against single member constituencies". The Reform Bill laid

down that the majority of the 670 constituencies were to be roughly

equal size and return one member; those between 50,000 and 165,000 kept

the two - member representation and those over 165,000 and all the

counties were split up into single - member constituencies. This franchise

existed until 1918.

He became Prime Minister of a minority administration from 1885 to 1886. In the November 1883 issue of National Review Salisbury wrote an article titled "Labourers' and Artisans' Dwellings" in which he argued that the poor conditions of working class housing were injurious to morality and health. Salisbury said "Laissez - faire is an admirable doctrine but it must be applied on both sides", as Parliament had enacted new building projects (such as the Thames Embankment) which had displaced working class people and was responsible for "packing the people tighter": "...thousands of families have only a single room to dwell in, where they sleep and eat, multiply, and die… It is difficult to exaggerate the misery which such conditions of life must cause, or the impulse they must give to vice. The depression of body and mind which they create is an almost insuperable obstacle to the action of any elevating or refining agencies". The Pall Mall Gazette argued that Salisbury had sailed into "the turbid waters of State Socialism"; the Manchester Guardian said his article was "State socialism pure and simple" and The Times claimed Salisbury was "in favour of state socialism". In July 1885 the Housing of the Working Classes Bill was introduced by Cross in the Commons and Salisbury in the Lords. When Lord Wemyss criticized the Bill as "strangling the spirit of independence and the self - reliance of the people, and destroying the moral fibre of our race in the anaconda coils of state socialism", Salisbury responded: "Do not imagine that by merely affixing to it the reproach of Socialism you can seriously affect the progress of any great legislative movement, or destroy those high arguments which are derived from the noblest principles of philanthropy and religion".

Although unable to accomplish much due to his lack of a parliamentary majority, the split of the Liberals over Irish Home Rule in

1886 enabled him to return to power with a majority, and, excepting a

Liberal minority government (1892 – 95), to serve as Prime Minister from

1886 to 1902.

In 1889 Salisbury set up the London County Council and then in 1890 allowed it to build houses. However he came to regret this, saying in November 1894 that the LCC, "is the place where collectivist and socialistic experiments are tried. It is the place where a new revolutionary spirit finds its instruments and collects its arms".

Salisbury caused controversy in 1888 after Gainsford Bruce had won the Holborn by-election for the Unionists, beating the Liberal Earl Compton. Bruce had won the seat with a smaller majority than Francis Duncan had for the Unionists in 1885. Salisbury explained this by saying in a speech in Edinburgh on 30 November: "But then Colonel Duncan was opposed to a black man, and, however great the progress of mankind has been, and however far we have advanced in overcoming prejudices, I doubt if we have yet got to the point where a British constituency will elect a black man to represent them... I am speaking roughly and using language in its colloquial sense, because I imagine the colour is not exactly black, but at all events, he was a man of another race". The "black man" was Dadabhai Naoroji, an Indian. Salisbury's comments were criticized by the Queen and by Liberals who believed that Salisbury had suggested that only white Britons could represent a British constituency. Three weeks later Salisbury delivered a speech at Scarborough, where he denied that "the word "black" necessarily implies any contemptuous denunciation. Such a doctrine seems to be a scathing insult to a very large proportion of the human race… The people whom we have been fighting at Suakim, and whom we have happily conquered, are among the finest tribes in the world, and many of them are as black as my hat". Furthermore "such candidatures are incongruous and unwise. The British House of Commons, with its traditions… is a machine too peculiar and too delicate to be managed by any but those who have been born within these isles". Naoroji was elected for Finsbury in 1892 and Salisbury invited him to become a Governor of the Imperial Institute, which he accepted.

Salisbury's government passed the Naval Defence Act 1889 which facilitated the spending of an extra £20 million on the Royal Navy over the following four years. This was the biggest ever expansion of the navy in peacetime: ten new battleships, thirty - eight new cruisers, eighteen new torpedo boats and four new fast gunboats. Traditionally (since the Battle of Trafalgar) Britain had possessed a navy one - third larger than their nearest naval rival but now the Royal Navy was set to the Two - Power Standard;

that it would be maintained "to a standard of strength equivalent to

that of the combined forces of the next two biggest navies in the

world". This was aimed at France and Russia.

In the aftermath of the general election of 1892, Balfour and Chamberlain wished to pursue a programme of social reform, which Salisbury believed would alienate "a good many people who have always been with us" and that "these social questions are destined to break up our party". When the Liberals and Irish Nationalists (which were a majority in the new Parliament) successfully voted against the government, Salisbury resigned the premiership on 12 August. His private secretary at the Foreign Office wrote that Salisbury "shewed indecent joy at his release".

Salisbury — in an article in November for the National Review entitled

‘Constitutional revision’ — said that the new government, lacking a

majority in England and Scotland, had no mandate for Home Rule and

argued that because there was no referendum only the House of Lords

could provide the necessary consultation with the nation on policies for

organic change. The

Lords defeated the second Home Rule Bill by 419 to 41 in September 1893

but Salisbury stopped them from opposing the Liberal Chancellor's death

duties in 1894. The general election of 1895 returned a large Unionist majority.

Salisbury's expertise was in foreign affairs. For most of his time as Prime Minister he served not as First Lord of the Treasury, the traditional position held by the Prime Minister, but as Foreign Secretary. In that capacity, he managed Britain's foreign affairs, famously pursuing a policy of "Splendid Isolation". Among the important events of his premierships was the Partition of Africa, culminating in the Fashoda Crisis and the Second Boer War. At home he sought to "fight Home Rule with kindness" by launching a land reform programme which helped hundreds of thousands of Irish peasants gain land ownership.

On

11 July 1902, in failing health and broken hearted over the death of

his wife, Salisbury resigned. He was succeeded by his nephew, Arthur James Balfour.

Salisbury was offered a dukedom by Queen Victoria in 1886 and 1892, but declined both offers, citing the prohibitive cost of the lifestyle dukes were expected to maintain.

When Salisbury died his estate was probated at 310,336 pounds sterling.

Salisbury is seen as an icon of traditional, aristocratic conservatism. The Conservative historian Robert Blake considered Salisbury "the most formidable intellectual figure that the Conservative party has ever produced". In 1977 the Salisbury Group was founded, chaired by Robert Gascoyne - Cecil, 6th Marquess of Salisbury and named after the 3rd Marquess. It published pamphlets advocating conservative policies. The academic quarterly Salisbury Review was named in his honour upon its founding in 1982. The Conservative historian Maurice Cowling claimed that "The giant of conservative doctrine is Salisbury". It was on Cowling's suggestion that Paul Smith edited a collection of Salisbury's articles from the Quarterly Review. Andrew Jones and Michael Bentley wrote in 1978 that "historical inattention" to Salisbury "involves wilful dismissal of a Conservative tradition which recognizes that threat to humanity when ruling authorities engage in democratic flattery and the threat to liberty in a competitive rush of legislation".

Not long before his death in 1967, Clement Attlee (Labour Party Prime Minister, 1945 – 51) was invited to Chequers by Harold Wilson and was asked who he thought was the best Prime Minister of his lifetime. Attlee immediately replied: "Salisbury".

The 6th Marquess of Salisbury commissioned Andrew Roberts to write Salisbury's authorized biography, which was published in 1999.

After the Bering Sea Arbitration, Canadian Prime Minister Sir John Sparrow David Thompson said of Lord Salisbury's acceptance of the Arbitration Treaty that it was "one of the worst acts of what I regard as a very stupid and worthless life."

The British phrase 'Bob's your uncle' is thought to have derived from Robert Cecil's appointment of his nephew, Arthur Balfour, as Minister for Ireland.

Fort Salisbury (now Harare) was named in honour of the British prime minister, when founded in September 1890. Subsequently simply known as Salisbury, the city was subsequently the capital of: Southern Rhodesia, from 1890; the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, from 1953 to 1963; Rhodesia, from 1963 to 1979; Zimbabwe Rhodesia, in 1979; and finally Zimbabwe, from 1980. The name was changed to Harare in April 1982, on the second anniversary of Zimbabwe's creation.

Lord Salisbury was the second son of the 2nd Marquess of Salisbury, a minor Conservative politician. In 1857, he defied his father and married Georgina Alderson. She was the daughter of Sir Edward Alderson,

a moderately notable jurist and so of much lower social standing than

the Cecils. The marriage proved a happy one. Robert and Georgina had

eight children, all but one of whom survived infancy.

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was an influential British politician and statesman. Unlike most major politicians of the time, he was a self made businessman and had not attended Oxford or Cambridge University.

Born in London, Chamberlain made his career in Birmingham, first as a manufacturer of screws and then as a notable Mayor of the city. During his early adulthood he was a radical Liberal Party member and a campaigner for educational reform. He entered the House of Commons aged almost forty, relatively late in life for a front - rank politician. Rising to power through his influence with the Liberal grassroots organisation, he served as President of the Board of Trade in Gladstone's Second Government (1880 – 85). At the time, Chamberlain was notable for his attacks on the Conservative leader Lord Salisbury, and in the 1885 general election he proposed the "Unauthorised Programme" of benefits for newly enfranchised agricultural labourers. Chamberlain resigned from Gladstone's Third Government in 1886 in opposition to Irish Home Rule, and after the Liberal Party split he became a Liberal Unionist, a party which included a bloc of MPs based in and around Birmingham.

From the 1895 general election the Liberal Unionists were in coalition with the Conservative Party, under Chamberlain's former opponent Lord Salisbury. Chamberlain accepted the post of Secretary of State for the Colonies, declining other positions. In this job, he presided over the Second Boer War and was the dominant figure in the Unionist Government's re-election at the"Khaki Election" in 1900. In 1903, he resigned from the Cabinet to campaign for tariff reform. He obtained the support of most Unionist MPs for this stance, but the split contributed to the landslide Unionist defeat at the 1906 general election. Some months later, shortly after turning seventy, he was disabled by a stroke.

Despite

never becoming Prime Minister, he is regarded as one of the most

important British politicians of the late 19th and early 20th centuries,

as well as a renowned orator and an interesting character who split

both main parties. Winston Churchill later wrote of him that he was the

man "who made the weather". Chamberlain was the father – by different

marriages – of Sir Austen Chamberlain and Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain.

Chamberlain was born in Camberwell in London to a successful shoemaker and manufacturer, also named Joseph (1796 – 1874), and his wife Caroline Harben, daughter of Henry Harben. He was educated at University College School (then still in Euston) between 1850 and 1852, excelling academically and gaining prizes in French and mathematics.

The elder Chamberlain was not able to provide advanced education for all his children, and at the age of 16 years, Joseph was apprenticed to the Worshipful Company of Cordwainers and worked for the family business making quality leather shoes. At 18, he was sent to Birmingham to join his uncle's screwmaking business, Nettlefolds (later part of Guest, Keen and Nettlefolds), in which his father had invested. In partnership with Joseph Nettlefold, Chamberlain was to help the screwmaking firm, soon known as Nettlefold and Chamberlain, become a commercial success, and by the time of his retirement from the company, in 1874, it was exporting its products to the United States, Europe, India, Japan, Canada and Australia. During the business's most prosperous period, it produced approximately two - thirds of all metal screws made in England.

In 1860, Chamberlain met Harriet Kenrick, the daughter of Archibald Kenrick, member of a Unitarian family from Birmingham who originally occupied Wynn Hall in Ruabon, Wrexham, Wales. They were married in July 1861, and a daughter, Beatrice, was born to them in May 1862. In October 1863, Harriet, who had had a premonition that she would die in childbirth, gave birth to a son, Joseph Austen, the future Chancellor of the Exchequer and Foreign Secretary, but she became ill two days after the birth and died three days later. Chamberlain devoted himself to the growing fortunes of Nettlefold and Chamberlain, while raising Beatrice and Austen with the Kenrick parents - in - law.

In 1868, Chamberlain married for the second time, wedding Harriet's cousin, Florence Kenrick, daughter of Timothy Kenrick. The couple had four children: Arthur Neville in 1869, Ida in 1870, Hilda in 1871, and Ethel in 1873. On 13 February 1875, Florence gave birth to their fifth child, but she and the child died within a day.

Florence's sister, Louisa, married Joseph's brother, Arthur Chamberlain; their granddaughter was the author Elizabeth Longford and their great - granddaughter is the Labour politician Harriet Harman.

There were strong radical and liberal traditions among shoemakers in his adopted home city of Birmingham, while Chamberlain's Unitarian church had a long tradition of social action. Chamberlain duly became involved in Liberal politics, and the growth of Britain's urban population led to mounting national political pressure to redistribute parliamentary seats and to enfranchise a sizeable proportion of urban males. In 1866, Lord John Russell's Liberal administration submitted a Reform Bill to the House of Commons, designed to create 400,000 new voters. While conservative supporters of the government, known as 'Adullamites', opposed the Bill for its disruption of the social order, Radicals criticized it on the basis that it failed to concede the secret ballot or household suffrage. The Bill was defeated and Lord Derby formed a minority Conservative administration. On 27 August 1866, a large demonstration for reform was held in Birmingham, in which the Mayor marched alongside 250,000 people, one of whom was Chamberlain. John Bright addressed the huge middle and working class crowd, Chamberlain recalling that 'men poured into the hall, black as they were from the factories... the people were packed together like herrings.' The Conservative government passed a Reform Bill in 1867, nearly doubling the electorate from 1,430,000 to 2,470,000 and in the United Kingdom general election, 1868, the Liberal Party gained power. Chamberlain was active in the election campaign, praising Bright and George Dixon, a Birmingham Member of Parliament (MP).

In 1867 he helped found the Birmingham Education League with Jesse Collings. The Education League noted that of about four and a quarter million children of school age, two million children, mostly in urban areas, did not attend school, with a further million in uninspected schools. More contentious was the government's aid to Church of England schools, embodying an association between official religion and state that was bound to offend Nonconformist opinion. Chamberlain was enthusiastic about the requirement for the provision of free, secular, compulsory education, stating that 'it is as much the duty of the State to see that the children are educated as to see that they are fed.' He also pointed to the success owed by the United States and Prussia to public education. The Birmingham Education League evolved into the National Education League, which held its first Conference in Birmingham in 1869. The League proposed a school system funded by local rates and government grants, managed by local authorities subject to government inspection. By 1870, the League had more than one hundred branches, mostly in cities and peopled largely by men of trades unions and working men's organizations. Chamberlain was also influential in the local campaign in support of Gladstone's Irish Church Disestablishment Bill against the House of Lords's obstructionism. Chamberlain seconded the motion for disestablishment at a debate in Birmingham town hall, and he addressed the large, restless crowd protesting the hereditary powers of the House of Lords. The meeting ended amidst fighting, but Chamberlain had become influential among Birmingham Liberals, and he was elected to Birmingham Council for St. Paul's ward in November 1869.

The Liberal government proposed an Elementary Education Bill in January 1870. William Edward Forster, Vice - President of the Committee of Council on Education was responsible for the Bill and was criticized by Nonconformists because of the legislation's proposal to maintain church schools as part of the national educational system and to fund them by the rates. The absence of school commissions or the provision of free, compulsory education caused consternation among the National Education League, and Chamberlain arranged for a large delegation to visit the Prime Minister's residence at 10 Downing Street to persuade PM Gladstone to remove the role of the church in national education. On 9 March 1870, the Education League's delegation arrived to meet the Prime Minister, consisting of 400 branch members and 46 M.P.s. In this first meeting between Gladstone and Chamberlain, the latter impressed the Prime Minister with his lucid speech, and Gladstone agreed during the Elementary Education Bill's second reading to make amendments that removed church schools from rate - payer control and granted them funding from government funds. Liberal MPs, exasperated at the compromises in the legislation, voted against the government, and the Bill passed the House of Commons with support from the Conservatives. Chamberlain campaigned against the Act, and especially clause 25, which gave school boards of England and Wales the power to pay the fees of poor children at voluntary schools, which theoretically allowed them to fund church schools. The Education League even stood in several by-elections against Liberal candidates who refused to support the repeal of clause 25. In 1873 a Liberal majority was elected to the Birmingham School Board, with Chamberlain as chairman. Eventually, a compromise was reached with the church component of the School Board agreeing to make payments from rate - payer's money only to schools associated with industrial education.

Chamberlain

broadened his campaigning to take up the cause of rural workers,

promoting their enfranchisement and cheaper land prices. This was

represented in his subsequent slogan, coined in an article written for

the Fortnightly Review,

the four 'Fs' – 'Free Church, Free Schools, Free Land and Free Labour'.

In another article entitled 'The Liberal Party and its Leaders',

Chamberlain criticized Gladstone's leadership and advocated a concerted

Radical challenge to the direction of the party. By 1873, Chamberlain

had made his reputation, especially in Birmingham, as a charismatic

Radical politician, and sought to further his cause in municipal

politics.

In November 1873 Chamberlain campaigned as a Liberal candidate for the mayoralty of Birmingham, with the Conservatives denouncing his political Radicalism and disparaging him as a 'monopoliser and a dictator.' The Liberal Party swept the municipal elections having campaigned with the slogan 'The People above the Priests', a criticism of the High Toryism of Chamberlain's opponents. As mayor, Chamberlain promoted many civic improvements, leaving the town (in words to Collings) 'parked, paved, assized, marketed, gas & watered and improved'. Prior to his tenure in office, the city's municipal administration was notably lax with regards to public works, and many urban dwellers lived in conditions of great poverty.

The city's water supply was considered a danger to public health – approximately half of the city's population was dependent on well water, much of which was polluted by sewage. Furthermore, piped water was only supplied three days per week, compelling the use of unhealthy well water and water carts for the rest of the week. Two rival gas companies — the Birmingham Gas Company and the Birmingham and Staffordshire Gas Company — were locked in constant competition, in which the city's streets were continually dug up to allow for the laying of mains. Chamberlain established a municipal gas supply by forcibly purchasing the two companies on behalf of the borough for £1,953,050, even offering to purchase the companies himself if the ratepayers refused. The move was a success, and in its first year of operations, the municipal gas scheme made a profit of £34,000.

Deploring the rising death rate from contagious diseases in the poorest sections of the city, in January 1876, Chamberlain forcibly purchased Birmingham's waterworks for a combined sum of £1,350,000, creating Birmingham Corporation Water Department, having declared to a House of Commons Committee that 'We have not the slightest intention of making profit... We shall get our profit indirectly in the comfort of the town and in the health of the inhabitants'. Despite this noticeable executive action, Chamberlain was mistrustful of central authority and burdensome bureaucracy, preferring to give local communities the responsibility to act on their own initiative.

With the city's gas and water supply controlled by the municipality, Chamberlain initiated other schemes with the intention of improving the quality of life in Birmingham. In July 1875 Chamberlain tabled an improvement plan that involved slum clearance in Birmingham's city centre. Chamberlain had been consulted by the Home Secretary, Richard Assheton Cross during the preparation of the Artisan's and Labourers' Dwellings Improvement Act 1875, a major feature of the Disraeli ministry's programme of social improvement. Chamberlain proposed to build a new road, (Corporation Street), through Birmingham's overcrowded slums, and bought 50 acres (200,000 m²) of property for the purpose. Overriding the protests of local landlords and the Commissioner of the Local Government Board's inquiry into the scheme, Chamberlain appealed directly to the President of the Local Government Board, George Sclater - Booth. Having gained the endorsement of national government and raised the funds for the programme, Chamberlain was able to implement the scheme, contributing £10,000 to the cost himself. However, the Improvement Committee concluded that it would be too expensive to transfer slum dwellers to municipally built accommodation and so the land was leased as a business proposition on a 75 year lease. Those who had occupied the slums were eventually rehoused in the suburbs, not in the area of their previous residence, and the scheme as a whole cost local government £300,000. The death rate in the newly christened Corporation Street decreased dramatically – from approximately 53 per 1,000 between 1873 and 1875 to 21 per 1,000 between 1879 and 1881.

Chamberlain's tenure in office was also notable for his promotion of cultural improvement. Public and private money was used for the construction of libraries, municipal swimming pools and schools. The Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery was enlarged and a number of new parks were opened. Construction of the Council House was begun while the Victoria Law Courts were built on Corporation Street.

The

mayoralty helped give Chamberlain stature as a figure of both local and

national renown, with contemporaries commenting upon his youthfulness

and dress, including 'a black velvet coat, jaunty eyeglass in eye, red

neck - tie drawn through a ring'. His contribution to the city's

improvement earned Chamberlain the political allegiance of the so-called

'Birmingham caucus', a loyalty that would remain during his entire

public career.

In the 1874 general election, Chamberlain made his first attempt to become an MP of the House of Commons. The Sheffield Reform Association, an offshoot of the Liberal Party in the city, invited Chamberlain to stand for election soon after the beginning of his tenure as Mayor of Birmingham. The campaign was a fierce one, and Chamberlain was accused of republicanism and atheism by opponents, with dead cats even being thrown at him on the speaking platform by angry spectators. Much to his displeasure, Chamberlain came in third place, a failure for someone considered as a leading spokesman for urban Radicalism. During his term as Mayor of Birmingham, Chamberlain continued to entertain the prospect of campaigning for Parliament, although he eventually rejected the possibility of campaigning in Sheffield. Predictably, Chamberlain maintained his focus on Birmingham and when George Dixon decided to retire from his parliamentary seat in May 1876, an opportunity was presented for Chamberlain to be elected to the House of Commons. On 17 June 1876, Chamberlain was returned unopposed for the Birmingham constituency, after a period of anxiety following his nomination in which he denounced the Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli, accusing him of being 'a man who never told the truth except by accident.' Chamberlain subsequently apologized publicly.

When elected, Chamberlain resigned the mayorship of Birmingham, and was introduced to the House of Commons by John Bright and Joseph Cowen, an M.P. for Newcastle - upon - Tyne. Almost immediately, Chamberlain began to organize the Radical component of the House of Commons in an attempt to prompt the Liberal leadership, with the intention of displacing Whig dominance and providing a Radical opposition to the Conservatives. On 4 August 1876, Chamberlain made his maiden speech in the House of Commons during a debate on elementary schools. The maintenance of clause 25 prompted Chamberlain to intervene, while Disraeli was present. Speaking for twenty minutes, Chamberlain utilized his experience on the Birmingham School Board to make an impressive speech. Hereafter, Chamberlain spoke on many subjects, but concentrated on the subject of free public education and female teachers. The issues of alcohol licensing and army discipline also occupied much of Chamberlain's time.

Early difficulties in creating a coherent group committed to Radicalism within the Liberal Party convinced Chamberlain of the need to establish a more effective organization for the party as a whole, especially in the localities. The controversy surrounding Disraeli's policy during the Russo - Turkish War proved to be a catalyst for activity, for Chamberlain viewed the agitation surrounding the Bulgarian atrocities as a means of utilizing public indignation for a Radical agenda. Chamberlain estimated that Radicalism could profit from Gladstone's increasing popularity, and he subsequently sought to close ranks with the returned Liberal leader. With the Liberal Party active in opposition to the Conservative government's foreign policy, it was a propitious moment to federate the country's Liberal Associations, and on 31 May 1877, Gladstone addressed approximately 30,000 people at Bingley Hall to found the National Liberal Federation. The body was undeniably a creation of Chamberlain's brand of Birmingham Radicalism, reflected in the dominance of Birmingham's politicians in the Federation's administration – Chamberlain himself served as President. The Federation was designed to tighten party discipline and provide the Liberal Party with the apparatus for fighting the Conservatives in elections. Furthermore, the Federation subsequently engaged in numerous campaigning activities, including the enlisting of new members, the organization of political meetings and the publishing of posters and pamphlets. Contemporary commentators made (often disparaging) comparisons between the techniques of the Federation and those employed in American politics. For Chamberlain, the Federation gave him much enhanced influence within the Liberal Party as well as a nationwide platform to promote Radicalism.

Chamberlain

was largely critical of Disraeli's foreign policy, arguing that the

Conservative government's forward policy diverted attention from the

requirements of domestic reform. Unlike many Liberals, Chamberlain's

attitude was not motivated by anti - imperialism, for although he berated

the government for its Eastern policy, the Second Afghan War of 1878 and the Zulu War of 1879, he had previously supported Disraeli's purchase of Suez Canal Company

shares in November 1875. At this stage of his career, Chamberlain was

eager to see the protection of British overseas interests, but placed

greater emphasis on a conception of justice in the pursuit of such

interests. In the 1880 general election,

Chamberlain joined the Liberal denunciations of the Conservative

Party's foreign policy, and the National Liberal Federation played an

important part in seeing the Liberal Party take power. With Gladstone

having returned as Prime Minister with notable assistance from the

National Liberal Federation, Chamberlain was hopeful of being rewarded

with a cabinet position.

Despite the fact that Chamberlain had sat in Parliament for only four years, his claims to a position in the cabinet were strong – he spoke nationally for Radicals and Nonconformists, and had a credible power base in the form of the National Liberal Federation. Although Gladstone did not regard the Federation highly, he recognized the part it had played in taking the Liberal Party to power, and appreciated the wisdom of not antagonizing Chamberlain, who told Sir William Harcourt that he was prepared to lead a revolt and field Radical candidates in borough elections. Eager to reconcile Radicals to the Whig heavy cabinet and having taken the counsel of Bright, Gladstone invited Chamberlain on 27 April 1880 to fulfil the post of President of the Board of Trade.

Chamberlain's scope for manoeuvre was restricted between 1880 and 1883 by the Cabinet's occupancy with difficulties concerning Ireland, Transvaal Colony and Egypt. However, he was able to introduce the Grain Cargoes Bill, for the safer transportation of grain, an Electric Lighting Bill, which enabled municipal corporations to establish electricity supplies, and a Seaman's Wages Bill, which ensured a fairer system of payment for seamen. After 1883, Chamberlain's period at the Board of Trade was more productive. A Bankruptcy Bill established a Bankruptcy Department at the Board of Trade responsible for enquiring into failed business deals. Meanwhile, a Patents Bill made patenting subject to supervision by the Board of Trade. Chamberlain also sought to end the practice of ship owners overinsuring their vessels – 'coffin ships' – while under - manning them, thereby ensuring a healthy profit irrespective of whether the ship arrived safely or sank. Despite being endorsed by Tory Democrats Lord Randolph Churchill and John Eldon Gorst, the Liberal government was unwilling to grant Chamberlain its full support and the Bill was withdrawn in July 1884.

In Cabinet, Ireland was of special interest to Chamberlain. Representing Irish Catholic peasants, the Irish Land League promoted fair rents, fixity of tenure and free sale, in opposition to absentee Anglo - Irish landlords. Chamberlain endorsed proposals that a Land Bill would be effective in countering agitation in Ireland and Fenian outrages in the British Isles. Furthermore, he believed that a land settlement would quieten demands for Irish Home Rule, something that Chamberlain opposed with vigour, reasoning that Ireland's separation from the United Kingdom would lead to the eventual break up of the British Empire. He was opposed to the policy of coercion advocated by the Chief Secretary for Ireland, W.E. Forster, believing that coercive tactics before the settlement of the land issue would provoke Irish malcontents. In April 1881, Gladstone's government introduced the Irish Land Act, but in response, Charles Stewart Parnell, leading the Irish nationalists, encouraged tenants to withhold rents. As a result, Parnell and other leaders, including John Dillon, were imprisoned in Kilmainham Gaol on 13 October 1881. Keen that there should be no more concessions, Chamberlain supported their imprisonment, and used their incarceration to bargain with them in 1882 in an attempt to reconcile them to the government.

In the ensuing 'Kilmainham Treaty', the government agreed to release Parnell in return for his cooperation in making the Land Act work. Forster resigned and the new Chief Secretary, Lord Frederick Cavendish, was murdered by Irish terrorists on 6 May 1882, leaving the 'Kilmainham Treaty' almost useless. Many, including Parnell, believed that Chamberlain, having brokered the agreement, would be offered the Chief Secretaryship, but Gladstone appointed Sir George Trevelyan instead. Nevertheless, Chamberlain maintained an interest in Irish affairs, and proposed to the Cabinet an Irish Central Board that would have legislative powers for land, education and communications. This was rejected by the Whigs in Cabinet on 9 May 1885.

Chamberlain's inability to introduce more creative legislation at the Board of Trade was the cause of frustration for someone who had proven to be so effective in municipal politics. However, Chamberlain viewed the Board of Trade as little more than a stepping stone for the attainment of higher things, seeing the post as a platform for the promotion of Radicalism. Early into the Gladstone ministry, Chamberlain suggested without success that the franchise should be extended, with the Prime Minister arguing that the matter should be deferred until the end of the Parliament's lifespan. In 1884, the parliament passed a major measure of franchise reform, the Reform Act, which gave hundreds of thousands of rural labourers the vote. This was followed by a Redistribution Act in 1885, negotiated by Gladstone and the Conservative leader, Lord Salisbury. Chamberlain sought to capture the newly enfranchised voters, and threw himself into a campaign of Radicalism. This included public meetings, speeches and, notably, articles written in the Fortnightly Review by Chamberlain's associates, including Jesse Collings and John Morley. Chamberlain earned a reputation for provocative speeches during the period, especially during debate on the 1884 County Franchise Bill, which was opposed by the Whig Liberals Lord Hartington and George Goschen, as well as Lord Salisbury, who argued that the Bill gave the Liberals an unfair electoral advantage. The Conservative politician was prepared to use the powers of the House of Lords in order to block the Bill, much to Chamberlain's dismay. At Denbigh, on 20 October 1884, Chamberlain famously declared in a speech that Salisbury was "himself the spokesman of a class – a class to which he himself belongs, who toil not neither do they spin."

In response, Salisbury branded Chamberlain a 'Sicilian bandit' and Stafford Northcote called him 'Jack Cade'.

When Chamberlain suggested that he would march on London with thousands

of Birmingham constituents to protest the House of Lords' powers,

Salisbury remarked that "Mr. Chamberlain will return from his adventure

with a broken head if nothing worse." This verbal altercation was

characteristic of the antagonism between Chamberlain and his Radical

endorsers on the one hand, and the landed Conservatives and Whigs on the

other. In July 1885, the Radical Programme, the first campaign handbook of British political history, was published, with a preface written by Chamberlain. It endorsed land reform, more direct taxation, free public education, the disestablishment of the Church of England, universal male suffrage, and more protection for trade unions. The proposals of the Radical Programme earned

the scorn of Whig Liberals and Conservatives alike, and it was the

former that Chamberlain had decided to oppose most actively, writing to

Morley that with Radical solidarity 'we will utterly destroy the Whigs,

and have a Radical government before many years are out.' Seeking a

contest with the Whigs, Chamberlain and Sir Charles Dilke presented their resignations to Gladstone on 20 May 1885, when the Cabinet

rejected Chamberlain's scheme for the creation of National Councils in

England, Scotland and Wales and when a proposed Land Purchase Bill did

not have any provision for the reform of Irish local government. The

resignations were not made public, and the opportunity for Chamberlain

to present his Radicalism to the country was only presented when the

Irish Parliamentary Party endorsed a Conservative amendment to the

budget on 9 June, which passed by 12 votes. Subsequently, the Gladstone

ministry resigned, and Salisbury formed a minority administration.

In August 1885, the Salisbury ministry asked for a dissolution of Parliament. At Hull on 5 August, Chamberlain began his election campaign by addressing an enthusiastic crowd in front of large posters declaring Chamberlain to be 'Your coming Prime Minister'. Until the campaign's end in October, Chamberlain denounced those in opposition to the proposals of the Radical Programme. In particular, he endorsed the cause of rural labourers and offered to make small holdings available to workers by funds from local authorities, using the slogan Three Acres and a Cow. Chamberlain's campaign proved to be immensely popular, with large crowds gathering to listen to his espousal of the Radical Programme. In particular, the young James Ramsay MacDonald and David Lloyd George were enthralled by Chamberlain's espousal of Radical policies, and leading Liberals noted with some discomfort the threat posed by what Goschen called the 'Unauthorised Programme'. The Conservatives denounced Chamberlain as an anarchist, with some even comparing him to Dick Turpin. In October, Chamberlain and Gladstone sought to eliminate a number of differences between their respective electoral programmes by a meeting at Hawarden Castle. The meeting, although good natured, was largely unproductive, and Gladstone neglected to tell Chamberlain of his negotiations with Parnell over proposals to grant Home Rule to Ireland. Chamberlain discovered the existence of such negotiations from Henry Labouchere, but unsure of the precise nature of Gladstone's offer to Parnell, did not press the issue, although he had already stated his opposition to Home Rule, arguing that Ireland had no more right to autonomy than London, declaring that "I cannot admit that five millions of Irishmen have any greater right to govern themselves without regard to the rest of the United Kingdom than the five million inhabitants of the metropolis." The Liberals won the general election in November 1885, but fell just short of an overall majority against the Conservatives and the Irish Nationalists, the latter holding the balance between the two parties.

On 17 December, Herbert Gladstone, son of William, revealed that his father was prepared to take office in order to implement a programme of Irish Home Rule, thereby doing what the press termed "flying the Hawarden Kite". At first, Chamberlain was reluctant to act in accordance with the anti - Home Rule Whigs and Conservatives, for fear of losing his Radical followers, and preferred to await the development of events. While saying little about the topic publicly, Chamberlain privately damned Gladstone and the concept of Home Rule to colleagues, believing that maintaining the Conservatives in power for a further year would make the Irish question easier to settle. In January 1886, a Radical inspired amendment was moved by Collings in the House of Commons which was carried by 79 votes. The Liberals assumed power, although tellingly, Hartington, Goschen and 18 Liberals had voted with the Conservatives. Gladstone assembled his third administration and offered Chamberlain the office of First Lord of the Admiralty, a suggestion Chamberlain declined. Gladstone rejected Chamberlain's preference for the Colonial Office and eventually appointed him President of the Local Government Board, a suitable post considering Chamberlain's associations with municipal government. A dispute over the amount to be paid to Collings, Chamberlain's Parliamentary Secretary, worsened relations between Gladstone and Chamberlain, although the latter was still hopeful that his membership of the Cabinet could result in Gladstone's Home Rule proposal being altered or abandoned, so that his programme of Radicalism could be given more attention. Chamberlain's renewed scheme for National Councils was not discussed in Cabinet, and only on 13 March were Gladstone's proposals for Ireland revealed. A Land Purchase Bill would accompany a Home Rule Bill, and Chamberlain argued that the details of the latter should be made known in order for a fair judgment to be made on the former. When Gladstone stated his intention to give Ireland a separate Parliament with full powers to deal with Irish affairs, Chamberlain resolved to resign, writing to inform Gladstone of his decision two days later. In the meantime, Chamberlain consulted with Arthur Balfour, Salisbury's nephew, over the possibility of concerted action with the Conservatives, and contemplated similar cooperation with the Whigs. His resignation was made public on 27 March 1886.

Despite

Chamberlain's liking for political combat, the prospects that he faced

in the aftermath of his resignation were far from promising. His chances

of attaining the leadership of the Liberal Party in the short term had

declined dramatically and in early May, the National Liberal Federation

declared its loyalty to Gladstone. On 9 April, Chamberlain spoke against

the Irish Home Rule Bill in

its first reading before attending a meeting of Liberal Unionists,

summoned by Hartington, hitherto the subject of Chamberlain's anti - Whig

declarations on 14 May. From this meeting arose the Liberal Unionist Association, originally an ad hoc alliance

to demonstrate the unity of anti - Home Rulers. Meanwhile, to

distinguish himself from the Whigs, Chamberlain founded the National

Radical Union

to rival the National Liberal Federation, which had since slipped from

his grasp. During its second reading on 8 June, the Home Rule Bill was

defeated by 30 votes, with 93 Liberals, including Chamberlain and

Hartington, voting against the government

Parliament was dissolved, and in the ensuing general election, the Conservatives and Liberal Unionists agreed to a defensive alliance. Chamberlain's predicament was more awkward than Hartington's, for the former was intensely mistrusted by, and unable to influence, the Conservatives, while he was despised by the Gladstonians for voting against Home Rule. Gladstone himself observed that "There is a difference between Hartington and Chamberlain, that the first behaves like and is a thorough gentleman. Of the other it is better not to speak." With the general election dominated by Home Rule, Chamberlain's campaign was characterized by a combination of Radicalism and intense patriotism. This proved to be immensely popular, and both the Conservatives and Liberal Unionists were able to benefit, taking 393 seats in the House of Commons and a comfortable majority.

Unlike Hartington and the Whigs, Chamberlain did not enter the Unionist government, aware that the hostility to him in the Conservative ranks meant that an agreement with them could extend merely to Ireland. Not wishing to alienate his Radical support base, Chamberlain refrained from a broader settlement. The Liberal mainstream cast Chamberlain as a villain, shouting "Judas!" and "Traitor!" as he entered the House of Commons chamber. Unable to associate himself decisively with either party, Chamberlain sought concerted action with a kindred spirit from the Conservative Party, Lord Randolph Churchill. In November 1886, Churchill announced his own 'Unauthorised Programme' at Dartford, the content of which had much in common with Chamberlain's own recent manifesto, including small holdings for rural labourers and greater local government. Next month, Churchill resigned as Chancellor of the Exchequer over military spending, and when the Conservative mainstream rallied around Salisbury, Churchill's career was effectively ended, along with Chamberlain's hope of creating a powerful cross party union of Radicals. The appointment of Goschen to the Treasury symbolized the increasingly good relationship between non - Radical Liberal Unionists and the Conservatives, thereby isolating Chamberlain further.

After January 1887, a series of Round Table Conferences took place between Chamberlain, Trevelyan, Harcourt, Morley and Lord Herschell,

in which the participants sought an agreement about the Liberal Party's

Irish policy. Chamberlain hoped that an accord would enable him to

claim the future leadership of the party and recognized the influence

over the Conservatives that could result from the negotiations merely

occurring. Although a preliminary agreement was made concerning land

purchase, Gladstone was unwilling to compromise further, and

negotiations ended by March. In August 1887, Lord Salisbury invited

Chamberlain to lead the British delegation in a Joint Commission to

resolve a fisheries dispute between the United States and Newfoundland.

Chamberlain had become increasingly disillusioned with politics, but

the visit to the United States renewed his enthusiasm, and enhanced his

standing with respect to Gladstone. In November, Chamberlain met

23 year old Mary Endicott, the daughter of President Grover Cleveland's Secretary of War, William C. Endicott,

at a reception in the British legation. Before he left the United

States in March 1888, Chamberlain proposed to Mary, describing her as

'one of the brightest and most intelligent girls I have yet met'. In

November 1888, Chamberlain married Mary in Washington, D.C., wearing

white violets, rather than his trademark orchid. Mary became a faithful supporter of his political ambitions.

Meanwhile, the Salisbury ministry was in the process of implementing a number of reforms that satisfied Chamberlain, in that Radicalism was making progress, surprisingly under a Conservative banner. Between 1888 and 1889, democratic County Councils were established in Great Britain. By 1891, measures for the provision of smallholdings had been made, and to Chamberlain's delight, the extension of free, compulsory education to the entire country. Chamberlain wrote that 'I have in the last five years seen more progress made with the practical application of my political programme than in all my previous life. I owe this result entirely to my former opponents, and all the opposition has come from my former friends.' Chamberlain also endeavoured to secure his Birmingham power base, for the Liberal Association in the city could no longer be relied upon to provide loyal support. He created the Liberal Unionist Association in 1888, associated with the National Radical Union, having extracted his supporters from the old Liberal organization. Chamberlain's reformation of Birmingham's political structure was successful, and in the 1892 general election, the Liberal Unionists won most of the city, even winning elections in neighbouring towns in the Black Country. By now, Chamberlain's son, Austen, had also entered the House of Commons. having been returned unopposed for East Worcestershire in March 1892. With Gladstone returned to power and unwilling to see Chamberlain back with the Liberal Party, and the Liberal Unionists reduced to 47 seats nationwide, a closer relationship with the Conservatives was increasingly necessary. A beginning was made when Hartington took his seat in the House of Lords as the Duke of Devonshire, allowing Chamberlain to assume the leadership of the Liberal Unionists in the House of Commons, resulting in a productive relationship with Balfour, leader of the Conservatives in the lower house.

Obliged to compromise with the Irish Nationalists, Gladstone introduced the Second Home Rule Bill in

February 1893, legislation that Chamberlain opposed with predictable

vigour. During the committee stage when he chastised the Gladstonian

Liberals, a fist fight broke out in which Chamberlain remained unmoved.

Although the Bill passed the House of Commons, the Lords rejected Home

Rule by a huge margin. With his party divided, Gladstone prepared to

dissolve Parliament on the issue of the House of Lords' veto, but was

compelled to resign in March 1894 by his colleagues, being replaced by Lord Rosebery.

While Rosebery neglected the topic of Home Rule, Chamberlain continued

to form alliances with the Conservatives, and spoke warily about socialism and the Independent Labour Party, which had one member in the House of Commons, Keir Hardie. Chamberlain warned of the dangers of socialism in his 1895 play The Game of Politics,

characterizing its proponents as the instigators of class conflict. In

response to the socialist challenge, he sought to divert the energy of

collectivism and use it for the good of Unionism, and continued to

propose reforms to the Conservatives. In his 'Memorandum of a Programme

for Social Reform' sent to Salisbury in 1894, Chamberlain made a number

of suggestions, including old age pensions, the provision of loans to

the working class for the purchase of houses, an amendment to the

Artisans' Dwellings Act to encourage street improvements, compensation

for industrial accidents, cheaper train fares for workers, tighter

border controls and shorter working hours. Salisbury was generally

sympathetic to the proposals, although somewhat guarded, yet his