<Back to Index>

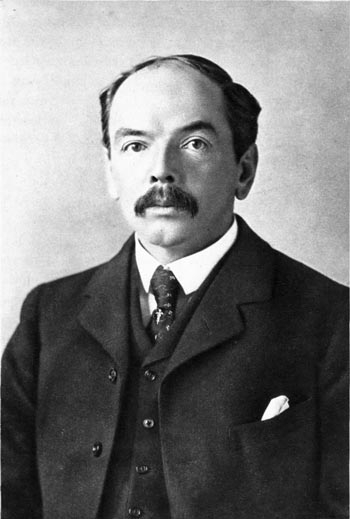

- 6th Prime Minister of the Cape Colony Cecil John Rhodes, 1853

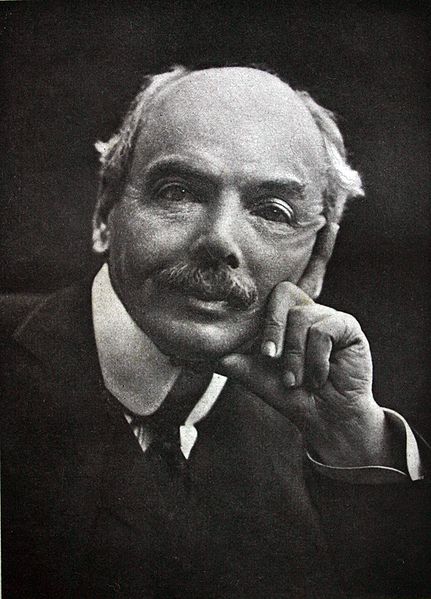

- 10th Prime Minister of the Cape Colony Leander Starr Jameson, 1853

PAGE SPONSOR

Cecil John Rhodes PC, DCL (5 July 1853 – 26 March 1902) was an English born South African businessman, mining magnate, and politician. He was the founder of the diamond company De Beers, which today markets 40% of the world's rough diamonds and at one time marketed 90%. An ardent believer in British colonial imperialism, he was the founder of the state of Rhodesia, which was named after him. In 1964, Northern Rhodesia became the independent state of Zambia and Southern Rhodesia was thereafter known as simply as Rhodesia. In 1980, Rhodesia, which had been de-facto independent since 1965, was granted independence by Britain and was renamed Zimbabwe. South Africa's Rhodes University is also named after Rhodes. He set up the provisions of the Rhodes Scholarship, which is funded by his estate.

Historian Richard A. McFarlane views Rhodes "as integral a participant in southern African and British imperial history as George Washington or Abraham Lincoln are

in their respective eras in United States history... most histories of

South Africa covering the last decades of the nineteenth century are

contributions to the historiography of Cecil Rhodes."

Rhodes was born in 1853 in Bishop's Stortford, Hertfordshire, England. He was the fifth son of the Reverend Francis William Rhodes and his wife Louisa Peacock Rhodes. His father was a Church of England vicar who was proud of never having preached a sermon longer than 10 minutes. His siblings included Francis William Rhodes, who became an army officer.

A sickly, asthmatic adolescent, Cecil Rhodes was taken out of grammar school and sent to Natal, South Africa, because his family thought the hot climate would improve his health. They expected he would help his older brother Herbert who operated a cotton farm.

According to Basil Williams, Rhodes

left grammar school, where he had studied since the age of nine, in

1869 "and continued his studies under his father's eye." However, "His

health was weakly and there were even fears that he might be consumptive,

a disease of which several of the family showed symptoms. His father

therefore determined to send him abroad to try the effect of a sea

voyage and a better climate. Herbert [Cecil's brother] had already set

up as a planter in Natal, so to join Herbert in Natal Cecil was

despatched on a sailing vessel. The voyage to Durban took him seventy

days, and on 1 September 1870 he first set foot on African soil, a tall,

lanky, anaemic, fair haired boy, shy and reserved in bearing." He

remained in Natal until October 1871, when he moved to the diamond

fields, just opening up.

After a brief stay with the Surveyor - General of Natal, Dr. P.C. Sutherland, in Pietermaritzburg, Rhodes took an interest in agriculture. He joined his brother Herbert on his cotton farm in the Umkomazi valley in Natal. The land was unsuitable for cotton, and the venture failed. When he first came to Africa, Rhodes lived on money lent by his aunt Sophia.

In October 1871, Rhodes and his brother Herbert left the colony for the diamond fields of Kimberley. Financed by N M Rothschild & Sons, over the next 17 years Rhodes succeeded in buying up all the smaller diamond mining operations in the Kimberley area. His monopoly of the world's diamond supply was sealed in 1889 through a strategic partnership with the London based Diamond Syndicate. They agreed to control world supply to maintain high prices. Rhodes supervised the working of his brother's claim and speculated on his behalf. Among his associates in the early days were John X. Merriman and Charles Rudd, who later became his partner in the De Beers Mining Company and Niger Oil Company.

During the 1880s Cape vineyards had been devastated by a phylloxera epidemic.

The diseased vineyards were dug up and replanted, and farmers were

looking for alternatives to wine. In 1892, Rhodes financed The Pioneer

Fruit Growing Company at Nooitgedacht, a venture created by Harry

Pickstone, an Englishman who had experience of fruit growing in

California. In 1896 he began to pay more attention to fruit farming and bought farms in Groot Drakenstein, Wellington and Stellenbosch. A year later, Rhodes bought Rhone and Boschendal and commissioned Sir Herbert Baker to build him a cottage there. The successful operation soon expanded into Rhodes Fruit Farms, and formed a cornerstone of the modern day Cape fruit industry.

Rhodes attended the Bishop's Stortford Grammar School. In 1873, Rhodes left his farm field in the care of his business partner, Rudd, and sailed for England to complete his studies. He was admitted to Oriel College, Oxford, but stayed for only one term in 1873. He returned to South Africa and did not return for his second term at Oxford until 1876. He was greatly influenced by John Ruskin's inaugural lecture at Oxford, which reinforced his own attachment to the cause of British imperialism. Among his Oxford associates were James Rochfort Maguire, later a fellow of All Souls College and a director of the British South Africa Company, and Charles Metcalfe. Due to his university career, Rhodes admired the Oxford "system". Eventually he was inspired to develop his scholarship scheme: "Wherever you turn your eye — except in science — an Oxford man is at the top of the tree".

While attending Oriel College, Rhodes became a Freemason in

the Apollo University Lodge. Although initially he did not approve of

the organization, he continued to be a Freemason until his death in

1902. The failures of the Freemasons, in his mind, later caused him to

envisage his own secret society with the goal of bringing the entire

world under British rule.

Whilst at Oxford, Rhodes continued to prosper in Kimberley. Before his departure for Oxford, he and C.D. Rudd had moved from the Kimberley Mine to invest in the more costly claims of what was known as old De Beers (Vooruitzicht). It was named after Johannes Nicolaas de Beer and his brother, Diederik Arnoldus, who occupied the farm. After purchasing the land in 1839 from David Danser, a Koranna chief in the area, Fourie had allowed the de Beers and various other Afrikaner families to cultivate the land. The region extended from the Modder River via the Vet River up to the Vaal River.

In 1874 and 1875, the diamond fields were in the grip of depression, but Rhodes and Rudd were among those who stayed to consolidate their interests. They believed that diamonds would be numerous in the hard blue ground that had been exposed after the softer, yellow layer near the surface had been worked out. During this time, the technical problem of clearing out the water that was flooding the mines became serious. Rhodes and Rudd obtained the contract for pumping water out of the three main mines. It was during this period that Jim B. Taylor, still a young boy and helping to work his father's claim, first met Rhodes.

On 12 March 1880, Rhodes and Rudd launched the De Beers Mining Company after the amalgamation of a number of individual claims. With £200,000 of capital, the company, of which Rhodes was secretary, owned the largest interest in the mine.

In 1880, Rhodes prepared to enter public life at the Cape. With the earlier incorporation of Griqualand West into the Cape Colony under the Molteno Ministry in 1877, the area had obtained six seats in the Cape House of Assembly. Rhodes chose the constituency of Barkly West, a rural constituency in which Boer voters predominated. Barkly West remained faithful to Rhodes even after his support of the Jameson Raid against the Transvaal. He continued as its Member until his death.

When Rhodes became a member of the Cape Parliament, the chief goal of the assembly was to help decide the future of Basutoland. The ministry of Sir Gordon Sprigg was trying to restore order after the 1880 rebellion known as the Gun War. The Sprigg ministry had precipitated the revolt by applying its policy of disarming Africans to the Basuto. In 1890, Rhodes became Prime Minister of the Cape Colony and implemented laws that would benefit mine and industry owners. He introduced the Glen Grey Act to push black people from their lands and make way for industrial development. He also introduced educational reform to the area.

Rhodes' policies were instrumental in the development of British imperial policies in South Africa, such as the Hut tax. He did not, however, have direct political power over the Boer Republic of the Transvaal. He often disagreed with the Transvaal government's policies. He believed he could use his money and his power to overthrow the Boer government and install a British colonial government supporting mine owners' interests in its place.

In 1895, Rhodes supported an attack on the Transvaal, the infamous Jameson Raid, which proceeded with the tacit approval of Secretary of State for the Colonies Joseph Chamberlain.

The raid was a catastrophic failure. It forced Cecil Rhodes to resign

as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, sent his oldest brother Col. Frank Rhodes to jail in Transvaal convicted of high treason and nearly sentenced to death, and led to the outbreak of both the Second Matabele War and the Second Boer War.

Rhodes used his wealth and that of his business partner Alfred Beit and other investors to pursue his dream of creating a British Empire in new territories to the north by obtaining mineral concessions from the most powerful indigenous chiefs. Rhodes' competitive advantage over other mineral prospecting companies was his combination of wealth and astute political instincts, also called the 'imperial factor', as he used the British Government. He befriended its local representatives, the British Commissioners, and through them organized British protectorates over the mineral concession areas via separate but related treaties. In this way he obtained both legality and security for mining operations. He could then win over more investors. Imperial expansion and capital investment went hand in hand.

The imperial factor was a double edged sword: Rhodes did not want the bureaucrats of the Colonial Office in

London to interfere in the Empire in Africa. He wanted British settlers

and local politicians and governors to run it. This put him on a

collision course with many in Britain, as well as with British missionaries,

who favoured what they saw as the more ethical direct rule from London.

Rhodes won because he would pay to administer the territories north of

South Africa against future mining profits. The Colonial Office did not

have the funds to do it. Rhodes promoted his business interests as in

the strategic interest of Britain: preventing the Portuguese, the Germans or the Boers from

moving in to south - central Africa. Rhodes' companies and agents

cemented these advantages by obtaining many mining concessions, as

exemplified by the Rudd and Lochner Concessions.

Rhodes had already tried and failed to get a mining concession from Lobengula, king of the Ndebele of Matabeleland. In 1888 he tried again. He sent John Moffat, son of the missionary Robert Moffat, who was trusted by Lobengula, to persuade the latter to sign a treaty of friendship with Britain, and to look favourably on Rhodes' proposals. His agent Francis Thompson, who had travelled to Bulawayo in the company of Charles Rudd and Rochfort Maguire, assured Lobengula that no more than ten white men would mine in Matabeleland. This limitation was left out of the document which Lobengula signed, known as the Rudd Concession. Furthermore it stated that the mining companies could do anything necessary to their operations. When Lobengula discovered later the true effects of the concession, he tried to renounce it, but the British Government ignored him.

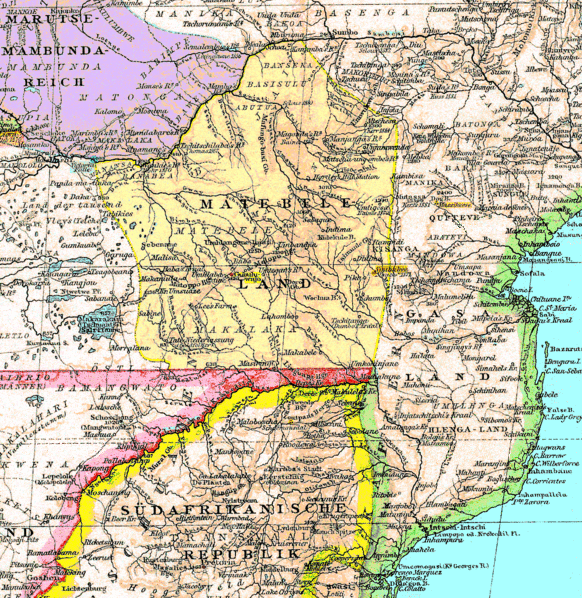

Armed with the Rudd Concession, in 1889 Rhodes obtained a charter from the British Government for his British South Africa Company (BSAC) to rule, police and make new treaties and concessions from the Limpopo River to the great lakes of Central Africa. He obtained further concessions and treaties north of the Zambezi, such as those in Barotseland (the Lochner Concession with King Lewanika in 1890, which was similar to the Rudd Concession); and in the Lake Mweru area (Alfred Sharpe's 1890 Kazembe concession). Rhodes also sent Sharpe to get a concession over mineral rich Katanga, but met his match in ruthlessness: when Sharpe was rebuffed by its ruler Msiri, King Leopold II of Belgium obtained a concession over Msiri's dead body for his Congo Free State.

Rhodes also wanted Bechuanaland Protectorate (now Botswana) under the BSAC charter. But three Tswana kings, including Khama III, travelled to Britain and won over British public opinion for it to remain governed by the British Colonial Office in London. Rhodes commented: "It is humiliating to be utterly beaten by these niggers."

The British Colonial Office also decided to administer British Central Africa (Nyasaland, today's Malawi) owing to the activism of Scots missionaries trying to end the slave trade. Rhodes paid much of the cost so that the British Central Africa Commissioner Sir Harry Johnston,

and his successor Alfred Sharpe, would assist with security for Rhodes

in the BSAC's north - eastern territories. Johnston shared Rhodes'

expansionist views, but he and his successors were not as pro-settler as

Rhodes, and disagreed on dealings with Africans.

The BSAC had its own police force, the British South Africa Police which was used to control Matabeleland and Mashonaland, in present day Zimbabwe. The company had hoped to start a "new Rand" from the ancient gold mines of the Shona. Because the gold deposits were on a much smaller scale, many of the white settlers who accompanied the BSAC to Mashonaland became farmers rather than miners. When the Ndebele and the Shona — the two main, but rival peoples — separately rebelled against the coming of the European settlers, the BSAC defeated them in the two Matabele Wars (1893 – 94; 1896 – 97). Shortly after learning of the assassination of the Ndebele spiritual leader, Mlimo, by the American scout Frederick Russell Burnham, Rhodes walked unarmed into the Ndebele stronghold in Matobo Hills. He persuaded the Impi to lay down their arms, thus ending the Second Matabele War.

By the end of 1894, the territories over which the BSAC had concessions or treaties, collectively called "Zambesia" after the Zambezi River flowing through the middle, comprised an area of 1,143,000 km² between the Limpopo River and Lake Tanganyika. In May 1895, its name was officially changed to "Rhodesia", reflecting Rhodes' popularity among settlers who had been using the name informally since 1891. The designation Southern Rhodesia was officially adopted in 1898 for the part south of the Zambezi, which later became Zimbabwe; and the designations North - Western and North - Eastern Rhodesia were used from 1895 for the territory which later became Northern Rhodesia, then Zambia.

Rhodes

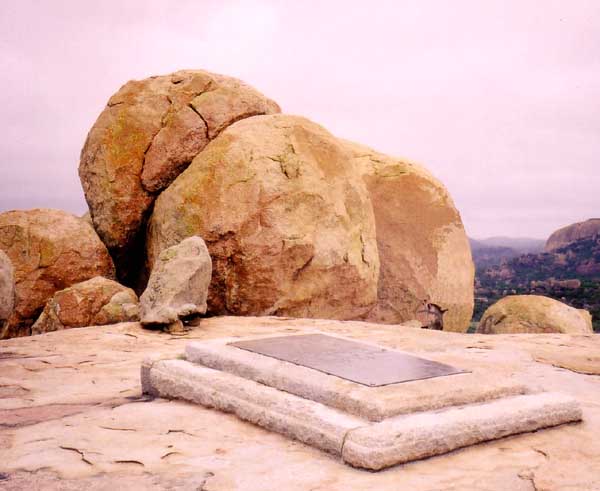

decreed in his will that he was to be buried in Matobo Hills. After his

death in the Cape in 1902, his body was transported by train to Bulawayo. His burial was attended by Ndebele chiefs, who asked that the firing

party should not discharge their rifles as this would disturb the

spirits. Then, for the first time, they gave a white man the Matabele

royal salute, Bayete. Rhodes was buried alongside Leander Starr Jameson and 34 British soldiers killed in the Shangani Patrol.

One of Rhodes' dreams (and the dream of many other members of the British Empire) was for a "red line" on the map from the Cape to Cairo. (On geo - political maps, British dominions were always denoted in red or pink.) Rhodes had been instrumental in securing southern African states for the Empire. He and others felt the best way to "unify the possessions, facilitate governance, enable the military to move quickly to hot spots or conduct war, help settlement, and foster trade" would be to build the "Cape to Cairo Railway".

This

enterprise was not without its problems. France had a rival strategy in

the late 1890s to link its colonies from west to east across the

continent. The Portuguese produced the "Pink Map", representing their claims to sovereignty in Africa.

Rhodes wanted to expand the British Empire because he believed that the Anglo - Saxon race was destined to greatness. In his last will and testament, Rhodes said of the British, "I contend that we are the first race in the world and that the more of the world we inhabit the better it is for the human race." He wanted to make the British Empire a superpower in which all of the British - dominated countries in the empire, including Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Cape Colony, would be represented in the British Parliament. Rhodes included American students as eligible for the Rhodes scholarships. He said that he wanted to breed an American elite of philosopher - kings who would have the United States rejoin the British Empire. As Rhodes also respected the Germans and admired the Kaiser, he allowed German students to be included in the Rhodes scholarships. He believed that eventually the United Kingdom (including Ireland), the USA and Germany together would dominate the world and ensure peace.

On domestic politics within the United Kingdom, Rhodes was a supporter of the Liberal Party. Rhodes' only major impact on domestic politics within the United Kingdom was his support of the Irish nationalist party, led by Charles Stewart Parnell (1846 – 1891). He contributed a great deal of money to the Irish nationalists, although Rhodes made his support conditional upon an autonomous Ireland's still being represented in the British Parliament. Rhodes was such a strong supporter of Parnell that, after the Liberals and the Irish nationalists disowned him after he was wrongly accused of committing adultery with the wife of another Irish nationalist, and was only cleared after a long court battle, Rhodes continued his support.

Rhodes was more tolerant of the Dutch speaking whites in the Cape Colony than were the other English speaking whites in the Cape Colony. He supported teaching Dutch as well as English in public schools in the Cape Colony and lent money to support this cause. While Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, he helped to remove most of the legal disabilities that English speaking whites had imposed on Dutch speaking whites. He was a friend of Jan Hofmeyr, leader of the Afrikaner Bond, and it was largely because of Afrikaner support that he became Prime Minister of the Cape Colony. Rhodes advocated greater self - government for the Cape Colony, in line with his preference for the empire to be controlled by local settlers and politicians rather than by London.

Confusingly

for the modern reader, self - government of the type Rhodes supported was

known as "colonialism". The opposed policy, direct control of a colony

from London, was known as "imperialism". This should be kept in mind

when reading documents from this time.

Rhodes never married, pleading "I have too much work on my hands" and saying that he would not be a dutiful husband. Some writers and academics have suggested that Rhodes may have been homosexual.

The scholar Richard Brown observed: "there is still the simpler but major problem of the extraordinarily thin evidence on which the conclusions about Rhodes are reached. Rhodes himself left few details... Indeed, Rhodes is a singularly difficult subject... since there exists little intimate material – no diaries and few personal letters."

Brown also comments: "On the issue of Rhodes' sexuality... there is, once again, simply not enough reliable evidence to reach firm, irrefutable conclusions. It is inferred, but not proved, that Rhodes was homosexual and it is assumed (but not proved) that his relationships with men were sometimes physical. Neville Pickering is described as Rhodes' lover in spite of the absence of decisive evidence."

Rhodes

was close to Pickering; he returned from negotiations for Pickering's

25th birthday in 1882. On that occasion, Rhodes drew up a new will

leaving his estate to Pickering. Two

years later, Pickering suffered a riding accident. Rhodes nursed him

faithfully for six weeks, refusing even to answer telegrams concerning

his business interests. Pickering died in Rhodes' arms, and at his

funeral Rhodes was said to have wept with fervor.

His successor was Henry Latham Currey, the son of an old friend, who had become Rhodes's private secretary in 1884. When Currey got engaged in 1894, Rhodes was deeply mortified and their relationship split.

Rhodes also remained close to Leander Starr Jameson after the two had met in Kimberley, where they shared a bungalow. In 1896 Earl Grey came to give Rhodes bad news. Rhodes instantly jumped to the conclusion that Jameson, who was ill, had died. On learning that his house had burnt down he commented, "Thank goodness. If Dr. Jim had died, I should never have got over it." Jameson nursed Rhodes during his final illness, was a trustee of his estate and residuary beneficiary of his will, which allowed him to continue living in Rhodes' mansion after his death. Rhodes' secretary, Jourdan, who was present shortly after Rhodes' death said, "Jameson was fighting against his own grief ... No mother could have displayed more tenderness towards the remains of a loved son". Jameson died in England in 1917, but after the war in 1920 his body was transferred to a grave beside that of Rhodes on Malindidzimu Hill or World's View, a granite hill in the Matopo National Park 40 km south of Bulawayo.

In the last years of his life, Rhodes was stalked by Polish princess Catherine Radziwiłł, born Rzewuska, married into a noble Polish - Lithuanian dynasty called Radziwiłł.

Radziwiłł falsely claimed that she was engaged to Rhodes, or that they

were having an affair. She asked him to marry her, but Rhodes refused.

She got revenge by falsely accusing him of loan fraud. He had to go to

trial and testify against her accusation. He died shortly after the

trial in 1902. She wrote a biography of Rhodes called Cecil Rhodes: Man and Empire Maker. Her accusations were eventually proved false.

During the Boer Wars Rhodes went to Kimberley at the onset of the siege, in a calculated move to raise the political stakes on the government to dedicate resources to the defence of the city. The military felt he was more of a liability than an asset and found him intolerable. In particular, Lieutenant Colonel Keke wich disliked Rhodes because of Rhodes' inability to cooperate with the military; Rhodes insisted that the military should adopt his plans and ideas instead of following their orders. Despite the differences, Rhodes' company was instrumental in the defence of the city, providing water, refrigeration facilities, constructing fortifications, manufacturing an armoured train, shells and a one - off gun named Long Cecil.

Rhodes

used his position and influence to lobby the British government to

relieve the siege of Kimberley, claiming in the press that the situation

in the city was desperate. The military wanted to assemble a large

force to take the Boer cities of Bloemfontein and Pretoria, but they were compelled to change their plans and send three separate smaller forces to relieve the sieges of Kimberley, Mafeking and Ladysmith.

Although Rhodes remained a leading figure in the politics of southern Africa, especially during the Second Boer War, he was dogged by ill health throughout his relatively short life. He was sent to Natal aged 16 because it was believed the climate might help problems with his heart. On returning to England in 1872 his health again deteriorated with heart and lung problems, to the extent that his doctor believed he would only survive six months. He returned to Kimberley where his health improved. From age 40 his heart condition returned with increasing severity until his death from heart failure in 1902, aged 48, at his seaside cottage in Muizenberg. The Government arranged an epic journey by train from the Cape to Rhodesia, with the funeral train stopping at every station to allow mourners to pay their respects. He was finally laid to rest at World's View, a hilltop located approximately 35 kilometres (22 mi) south of Bulawayo, in what was then Rhodesia. Today, his grave site is part of Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe.

In 2004, he was voted 56th in the SABC3 television series Great South Africans.

At his death he was considered one of the wealthiest men in the world. In his first will, of 1877, (before he had accumulated his wealth), Rhodes wanted to create a secret society that would bring the whole world under British rule. The exact wording from this will is:

To and for the establishment, promotion and development of a Secret Society, the true aim and object whereof shall be for the extension of British rule throughout the world, the perfecting of a system of emigration from the United Kingdom, and of colonisation by British subjects of all lands where the means of livelihood are attainable by energy, labour and enterprise, and especially the occupation by British settlers of the entire Continent of Africa, the Holy Land, the Valley of the Euphrates, the Islands of Cyprus and Candia, the whole of South America, the Islands of the Pacific not heretofore possessed by Great Britain, the whole of the Malay Archipelago, the seaboard of China and Japan, the ultimate recovery of the United States of America as an integral part of the British Empire, the inauguration of a system of Colonial representation in the Imperial Parliament which may tend to weld together the disjointed members of the Empire and, finally, the foundation of so great a Power as to render wars impossible, and promote the best interests of humanity.

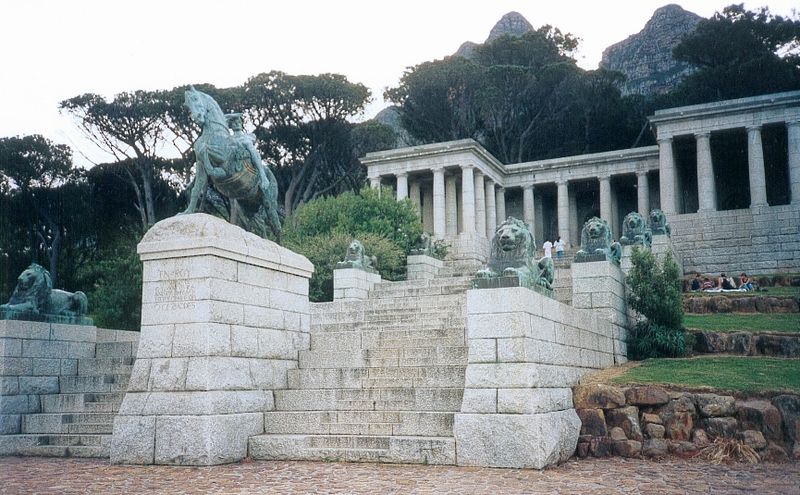

Rhodes' final will left a large area of land on the slopes of Table Mountain to the South African nation. Part of this estate became the upper campus of the University of Cape Town, another part became the Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden, while much was spared from development and is now an important conservation area.

In his last will and testament, he provided for the establishment of the famous Rhodes Scholarship, the

world's first international study programme. The scholarship enabled

students from territories under British rule, formerly under British

rule, and from Germany, to study at the University of Oxford.

Rhodes Memorial stands on Rhodes' favourite spot on the slopes of Devil's Peak, Cape Town, with a view looking north and east towards the Cape to Cairo route. Rhodes' house in Cape Town, Groote Schuur, was been inhabited by the President of the R.S.A. Jacob Zuma.

His birthplace was established as a museum in 1938, now known as Bishops Stortford Museum. The cottage in Muizenberg where he died is a South African national monument. The cottage today is operated as a museum by the Muizenberg Historical Conservation Society, and is open to the public. A broad display of Rhodes material can be seen, including the original De Beers board room table around which diamonds worth billions of dollars were traded.

Rhodes University College, now Rhodes University, in Grahamstown, was established in his name by his trustees and founded by Act of Parliament on 31 May 1904.

The

residents of Kimberley elected to build a memorial in Rhodes' honour in

their city, which was unveiled in 1907. The 72 ton bronze statue

depicts Rhodes on his horse, looking north with map in hand, and dressed

as he was when met the Ndebele after their rebellion.

- "To think of these stars that you see overhead at night, these vast worlds which we can never reach. I would annexe the planets if I could; I often think of that. It makes me sad to see them so clear and yet so far."

- “Pure philanthropy is very well in its way but philanthropy plus five percent is a good deal better.”

- "I contend that we are the first race in the world, and that the more of the world we inhabit the better it is for the human race... If there be a God, I think that what he would like me to do is paint as much of the map of Africa British Red as possible..."

- "In order to save the forty million inhabitants of the United Kingdom from a bloody civil war, our colonial statesmen must acquire new lands for settling the surplus population of this country, to provide new markets... The Empire, as I have always said, is a bread and butter question"

- "Remember that you are an Englishman, and have consequently won first prize in the lottery of life."

- "Equal Rights for all Civilized Men South of the Zambesi"

Sir Leander Starr Jameson, 1st Baronet, KCMG, CB, (9 February 1853 – 26 November 1917), also known as "Doctor Jim", "The Doctor" or "Lanner", was a British colonial statesman who was best known for his involvement in the Jameson Raid.

He was born on 9 February 1853, of the Jameson family of Edinburgh, Scotland, the son of Robert William Jameson (1805 – 1868), a Writer to the Signet, and Christian Pringle, daughter of Major General Pringle of Symington. Robert William and Christian Jameson had twelve children, of whom Leander Starr was the youngest, born at Stranraer, Galloway, in the south - west of Scotland, great - nephew of Professor Robert Jameson, Regius Professor of Natural History at the University of Edinburgh. Fort's biography of Jameson notes that Starr's '...chief Gamaliel, however, was a Professor Grant, a man of advanced age, who had been a pupil of his great - uncle, the Professor of Natural History at Edinburgh.'

Leander Starr Jameson's somewhat unusual name resulted from the fact that his father Robert William Jameson had been rescued from drowning on the morning of his birth by an American traveller, who fished him out of a canal or river with steep banks into which William had fallen while on a walk awaiting the birth of his son. The kindly stranger named "Leander Starr" was promptly made a godfather of the baby, who was named after him. His father, Robert William, started his career as an advocate in Edinburgh, and was Writer to the Signet, before becoming a playwright, published poet and editor of the Wigtownshire Free Press.

A radical and reformist, Robert William Jameson was the author of the dramatic poem Nimrod (1848) and Timoleon, a tragedy in five acts informed by the anti - slavery movement. Timoleon was performed at the Adelphi Theatre in Edinburgh in 1852, and ran to a second edition. In due course, the Jameson family moved to London, England, living in Chelsea and Kensington. Leander Starr Jameson went to the Godolphin School in Hammersmith, where he did well in both lessons and games prior to his university education.

L.S. Jameson was educated for the medical profession at University College Hospital, London, for which he passed his entrance examinations in January, 1870. He distinguished himself as a medical student, becoming a Gold Medallist in materia medica. After qualifying as a doctor, he was made Resident Medical Officer at University College Hospital (M.R.C.S. 1875; M.D. 1877).

After acting as house physician, house surgeon and demonstrator of anatomy, and showing promise of a successful professional career in London, his health broke down from overwork in 1878, and he went out to South Africa and settled down in practice at Kimberley. There he rapidly acquired a great reputation as a medical man, and, besides numbering President Kruger and the Matabele chief Lobengula among his patients, came much into contact with Cecil Rhodes.

Jameson was for some time the inDuna of the Matabele king's favourite regiment, the Imbeza. Lobengula expressed his delight with Jameson's successful medical treatment of his gout by honouring him with the rare status of inDuna. Although Jameson was a white man, he underwent the initiation ceremonies linked with this honour.

Jameson's status as an inDuna gave him advantages, and in 1888 he successfully exerted his influence with Lobengula to induce the chieftain to grant the concessions to the agents of Rhodes which led to the formation of the British South Africa Company; and when the company proceeded to open up Mashonaland, Jameson abandoned his medical practice and joined the pioneer expedition of 1890. From this time his fortunes were bound up with Rhodes' schemes in the north. Immediately after the pioneer column had occupied Mashonaland, Jameson, with F.C. Selous and A.R. Colquhoun, went east to Manicaland and was instrumental in securing the greater part of the country, to which Portugal was laying claim, for the Chartered Company. In 1891 Jameson succeeded Colquhoun as Administrator of Mashonaland. In 1893, Jameson was a key figure in the First Matabele War and involved in incidents that led to the massacre of the Shangani Patrol.

Jameson's character seems to have inspired a degree of devotion from his contemporaries. Elizabeth Longford writes

of him, "Whatever one felt about him or his projects when he was not

there, one could not help falling for the man in his presence.... People

attached themselves to Jameson with extraordinary fervour, the more

extraordinary because he made no effort to feed it. He affected an

attitude of tough cynicism towards life, literature and any articulate

form of idealism, particularly towards the hero - worship which he himself

excited ... When he died The Times estimated that his astonishing personal hold over his followers had been equalled only by that of Parnell, the Irish patriot."

Longford also notes that Rudyard Kipling wrote the poem If with Leander Starr Jameson in mind as an inspiration for the characteristics he recommended young people to live by (notably Kipling's son, to whom the poem is addressed in the last lines). Longford writes, "Jameson was later to be the inspiration and hero of Rudyard Kipling's poem, If...". Direct evidence that the poem 'If' was written about Jameson is available also in Rudyard Kipling's autobiography in which Kipling writes that "If --" was "drawn from Jameson's character."

As reported below, in 1895, Jameson led about 500 of his countrymen in what became known as The Jameson Raid against the Boers in southern Africa. The Jameson Raid was later cited by Winston Churchill as a major factor in bringing about the Boer War of 1899 to 1902. But the story as recounted in Britain was quite different. The British defeat was interpreted as a victory and Jameson was portrayed as a daring hero. The poem celebrates heroism, dignity, stoicism and courage in the face of the disaster of the failed Jameson Raid, for which he was wrongfully made a scapegoat.

Jameson's persuasive character, what became known later as 'the Jameson charm', was described in some detail by G.Seymour Fort (1918), who writes of his restless, logical and sagacious temperament in this way:

"... It was not his wont to talk at length, nor was he, unless exceptionally interested, a good listener. He was so logical and so quick to grasp a situation, that he would often cut short exposition by some forcible remark or personal raillery that would all too often quite disconcert the speaker.

Despite his adventurous career, mere reminiscences obviously bored him; he was always for movement, for some betterment of present or future conditions, and in discussion he was a master of the art of persuasion, unconsciously creating in those around him a latent desire to follow, if he would lead. The source of such persuasive influence eludes analysis, and, like the mystery of leadership, is probably more psychic than mental. In this latter respect, Jameson was splendidly equipped; he had greater power of concentration, of logical reasoning, and of rapid diagnosis, while on his lighter side he was brilliant in repartee and in the exercise of a badinage that was both cynical and personal...

....

He wrapped himself in cynicism as with a cloak, not only to protect

himself against his own quick human sympathy, but to conceal the austere

standard of duty and honour that he always set to himself. He was ever

trying to hide from his friends his real attitude towards life, and the

high estimate he placed upon accepted ethical values... He was

essentially a patriot who sought for himself neither wealth, nor power,

nor fame, nor leisure, nor even an easy anchorage for reflection. The

wide sphere of his work and achievements, and the accepted dominion of

his personality and his influence were both based upon his adherence to

the principle of always subordinating personal considerations to the

work in hand, upon the loyalty of his service to big ideals. His whole

life seems to illustrate the truth of the saying that in self - regard and

self - centredness there is no profit, and that only in sacrificing

himself for impersonal aims can a man save his soul and benefit his

fellow men."

In November 1895, a piece of territory of strategic importance, the Pitsani Strip, part of the Bechuanaland Protectorate and bordering the Transvaal, was ceded to the British South Africa Company by the Colonial Office, overtly for the protection of a railway running through the territory. Cecil Rhodes, the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony and managing director of the Company was eager to bring South Africa under British dominion, and encouraged the disenfranchised Uitlanders of the Boer republics to resist Afrikaner domination.

Rhodes hoped that the intervention of the Company's private army could spark an Uitlander uprising, leading to the overthrow of the Transvaal government. Rhodes' forces were assembled in the Pitsani Strip for this purpose. Joseph Chamberlain informed Salisbury on Boxing Day that an uprising was expected, and was aware that an invasion would be launched, but was not sure when. The subsequent Jameson Raid was a debacle, leading to the invading force's surrender. Chamberlain, at Highbury, received a secret telegram from the Colonial Office on 31 December informing him of the beginning of the Raid.

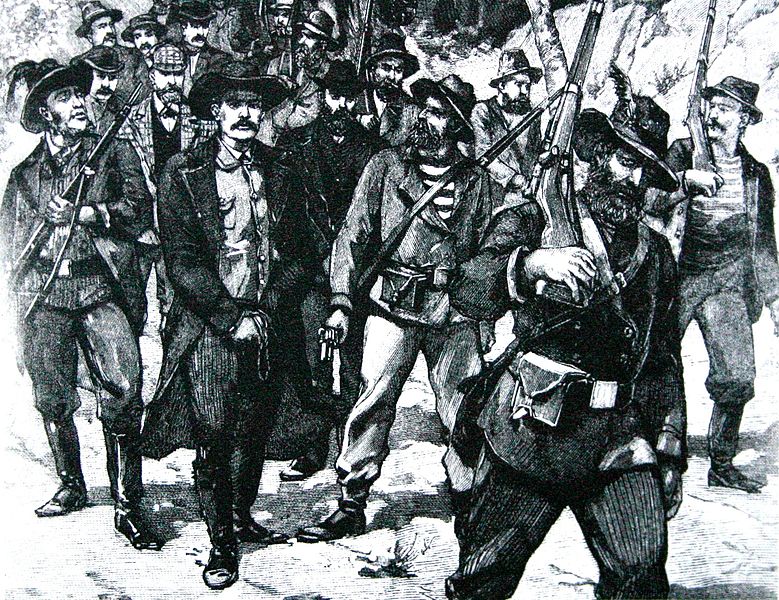

In 1895, Jameson assembled a private army outside the Transvaal in preparation for the violent overthrow of the Boer government. The idea was to foment unrest among foreign workers (Uitlanders) in the territory, and use the outbreak of open revolt as an excuse to invade and annexe the territory. Growing impatient, Jameson launched the Jameson Raid in December 1895, and managed to push within twenty miles of Johannesburg before superior Boer forces compelled him and his men to surrender.

Sympathetic

to the ultimate goals of the Raid, Chamberlain was uncomfortable with

the timing of the invasion and remarked that "if this succeeds it will

ruin me. I'm going up to London to crush it". He swiftly travelled by

train to the Colonial Office, ordering Sir Hercules Robinson,

Governor - General of the Cape Colony, to repudiate the actions of

Jameson and warned Rhodes that the Company's Charter would be in danger

if it were discovered that the Cape Prime Minister was involved in the

Raid. The prisoners were returned to London for trial, and the Transvaal

government received considerable compensation from the Company. Jameson

was tried in England for leading the raid; during that time he was

lionized by the press and London society.

The Jameson Raiders arrived in England at the end of February, 1896 to face trial. There were some months of investigations initially held at Bow Street, following which the 'trial at bar' (a legal procedure reserved only for very important cases) began on 20 June 1896, at the High Court of Judicature. The trial lasted seven days, following which Dr Jameson was 'found guilty and sentenced to imprisonment as a first - class misdemeanant for fifteen months. He was, however, released from Holloway in the following Dec on account of illness.'

During the trial of Jameson, Rhodes' solicitor, Bourchier Hawksley, refused to produce cablegrams that had passed between Rhodes and his agents in London during November and December 1895. According to Hawksley, these demonstrated that the Colonial Office 'influenced the actions of those in South Africa' who embarked on the Raid, and even that Chamberlain had transferred control of the Pitsani Strip to facilitate an invasion. Nine days before the Raid, Chamberlain had asked his Assistant Under - Secretary to encourage Rhodes to 'Hurry Up' because of the developing Venezuela Crisis of 1895.

The conduct of Dr Jameson during the trial was graphically described by Mary Krout in Looker on in London (1899), an eye witness account of her observations during the Jameson Raid trial. She wrote:

'....

Dr. Jameson was very grave and he, alone, was somewhat ill at ease. As

he entered the court room a dark flush mounted to his forehead, which

slowly faded as he walked to his chair and seated himself with great

deliberateness. He was a man somewhat below medium height, with a huge

head carried a little to one side, showing a remarkable breadth of brow;

the eyes were large, dark and sufficiently expressive, when not

concealed by the heavy drooping lids that were frequently half, or

wholly, closed; the nose was prominent and large and rather symmetrical,

the chin and mouth indicated decided firmness; the whole expression and

demeanour of the man evinced fearlessness that would be disposed to

express itself in deeds rather than words. He, too, was carefully

dressed in a dark frock coat and trousers, a spotless, white necktie and

pale grey gloves - the conventional morning dress of an English

gentleman. He walked with a heavy un elastic tread and a slightly

swinging carriage, and sat much of the time obliquely in his chair, one

cheek resting upon his elegantly gloved hand; his glance was often cast

down or fixed at rare intervals upon his counsel, Sir Edward Clarke; not

once during the day, so far as I could observe, did he give more than a

passing look at the witnesses upon the stand; to whatever was being

drawn out of them he seemed quite indifferent, and, except for that

first dull flush, he was equally oblivious of the spectators about him

to whom he was a manifest object of interest. Such was the hero of one

of the most daring raids in all the annals of border warfare; to all

appearance a quiet, modest gentleman, in faultless and fashionable

dress, with civilian stamped upon him from head to foot, and who would

have been recognised anywhere as the circumspect, model family

physician. He seemed pre-eminently a man to whom healing of wounds was

far more congenial and better suited than blood - letting with Maxim guns and Lee - Metford rifles, after the manner which he had so rashly undertaken.'

Jameson was sentenced to fifteen months in jail, but was soon pardoned. In June 1896, Chamberlain offered his resignation to Salisbury, having shown the Prime Minister one or more of the cablegrams implicating him in the Raid's planning. Salisbury refused to accept the offer, possibly reluctant to lose the government's most popular figure. Salisbury reacted aggressively in support of Chamberlain, supporting the Colonial Secretary's threat to withdraw the Company's charter if the cablegrams were revealed. Accordingly, Rhodes refused to reveal the cablegrams, and as no evidence was produced showing that Chamberlain was complicit in the Raid's planning, the Select Committee appointed to investigate the events surrounding the Raid had no choice but to absolve Chamberlain of all responsibility.

Jameson

had been Administrator General for Matabeleland at the time of the Raid

and his intrusion into Transvaal depleted Matabeleland of many of its

troops and left the whole territory vulnerable. Seizing on this

weakness, and a discontent with the British South Africa Company, the Matabele revolted in March 1896 in what is now celebrated in Zimbabwe as the First War of Independence – the Second Matabele War.

Hundreds of white settlers were killed within the first few weeks and

many more would die over the next year and a half at the hands of both

the Matabele and the Shona. With few troops to support them, the

settlers had to quickly build a laager in the centre of Bulawayo on

their own. Against over 50,000 Matabele held up in their stronghold of

the Matobo Hills as the settlers mounted patrols under such legendary

figures as Burnham, Baden - Powell, and Selous. After the Matabele laid down their arms, the war continued until October 1897 in Mashonaland.

Despite the Raid, Jameson had a successful political life following the invasion, receiving many honours in later life. In 1903 Jameson came forward as the leader of the Progressive (British) party in the Cape Colony. When the party was successful he became Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1904 to 1908. He served as the leader of the Unionist Party (South Africa) from its founding in 1910 until 1912. Jameson was created a baronet in 1911 and returned to England in 1912.

According to Rudyard Kipling, his famous poem "If— " was written in celebration of Leander Starr Jameson's personal qualities at overcoming the difficulties of the Raid, for which he largely took the blame, though Joseph Chamberlain, British colonial secretary of the day, was, according to some historians, implicated in the events of the raid. Jameson is buried at Malindidzimu Hill l or World's View, a granite hill in the Matobo National Park 40 km south of Bulawayo. It was designated by Cecil Rhodes as the resting place for those who served Great Britain well in Africa. Rhodes is also buried there.

Jameson died in the afternoon of Monday, 26 November 1917 in the City of London. His body was laid in a vault at Kensal Green Cemetery on 29 November 1917, where it remained until the end of the First World War.

Ian Colvin (1923) writes that Jameson's body was then:

"...carried to Rhodesia and on 22 May 1920, laid in a grave cut in the granite on the top of the mountain which Rhodes had called The View of the World, close beside the grave of his friend.

'Thy firmness makes my circle just, And makes me end where I begun.'

There on the summit those two lie together."

Jameson's life is the subject of a number of biographies, including The Life of Jameson by Ian Colvin (1922, Vol.1 and 1923, Vol.2), and Dr. Jameson by G. Seymour Fort, (1918). The Jameson Raid has been the subject of numerous articles and books, and remains a fascinating historical riddle more than one hundred years after the events of the Raid took place.

There are three portraits of Leander Starr Jameson in the National Portrait Gallery in London. One of these was by one of his older brothers, Middleton Jameson R.A., (1851 – 1919), otherwise known as 'Midge', to whom he was devoted. Leander Starr Jameson was awarded the KCMG, the CB, the Freedom of the City of London, Freedom of the City of Manchester, and Freedom of the City of Edinburgh for services to the British Empire.

To this day, the events surrounding Jameson's involvement in the Jameson Raid, being in general somewhat out of character with his prior history, the rest of his life and successful later political career, remain something of an enigma to historians. In 2002, The Van Riebeck Society published Sir Graham Bower’s Secret History of the Jameson Raid and the South African Crisis, 1895 – 1902, adding to growing historical evidence that the imprisonment and judgement upon the Raiders at the time of their trial was an underhanded move by the British government, a result of political manoeuvres by Joseph Chamberlain and his staff to hide his own involvement and knowledge of the Raid.

In his review of Sir Graham Bower’s Secret History ...Alan Cousins, notes that, 'A number of major themes and concerns emerge' from Bower's history, '... perhaps the most poignant being Bower’s accounts of his being made a scapegoat in the aftermath of the raid: "since a scapegoat was wanted I was willing to serve my country in that capacity".'

Cousins notes of Bower that 'a very clear sense of his rigid code of honour is plain, and a conviction that not only unity, peace and happiness in South Africa, but also the peace of Europe would be endangered if he told the truth. He believed that, as he had given Rhodes his word not to divulge certain private conversations, he had to abide by that, while at the same time he was convinced that it would be very damaging to Britain if he said anything to the parliamentary committee to show the close involvement of Sir Hercules Robinson and Joseph Chamberlain in their disreputable encouragement of those plotting an uprising in Johannesburg.'

Finally, Cousins observes that, '...in his reflections, Bower has a particularly damning judgement on Chamberlain, whom he accuses of ‘brazen lying’ to parliament, and of what amounted to forgery in the documents made public for the inquiry. In the report of the committee, Bower was found culpable of complicity, while no blame was attached to Chamberlain or Robinson. His name was never cleared during his lifetime, and Bower was never reinstated to what he believed should be his proper position in the colonial service: he was, in effect, demoted to the post of colonial secretary in Mauritius. The bitterness and sense of betrayal he felt come through very clearly in his comments.'

Speculation on the true nature of the behind - the - scenes story of the Jameson Raid has therefore continued for more than a hundred years after the events, and carries on to this day.