<Back to Index>

- Queen of Denmark, Norway and Sweden Margrete I Valdemarsdatter, 1353

PAGE SPONSOR

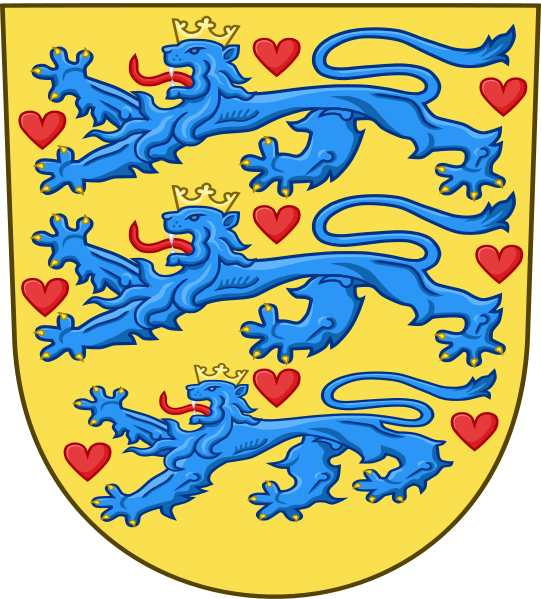

Margaret I (Danish: Margrete Valdemarsdatter, Norwegian: Margrete Valdemarsdotter, Swedish: Margareta Valdemarsdotter, Icelandic: Margrét Valdimarsdóttir) (1353 – 28 October 1412) was Queen of Denmark, Norway and Sweden and founder of the Kalmar Union, which united the Scandinavian countries for over a century. Although she acted as queen regnant, the laws of contemporary Danish succession denied her formal queenship. Her title in Denmark was derived from her father King Valdemar IV of Denmark. She became Queen of Norway and Sweden by virtue of her marriage to King Haakon VI of Norway.

She is known in Denmark as "Margrete I," to distinguish her from the current queen. Denmark did not have a tradition of allowing women to rule and so when her son died she was named "All - powerful Lady and Mistress (Regent) of the Kingdom of Denmark." She only styled herself Queen of Denmark during 1375. Margaret usually referred to herself as "Margaret, by the grace of God, Valdemar the King of Denmark's daughter" and "Denmark's rightful heir" when referring to her position in Denmark. Others simply referred to her as the "Lady Queen" without specifying what she was Queen (or female king) of, but not so Pope Boniface IX, who in his letters styled her "our beloved daughter in Christ, Margaret, most excellent queen of Denmark, Sweden and Norway."

With

regards to Norway, she was known as Queen (Queen - consort, then Dowager

Queen) and Regent. In Sweden, she was Dowager Queen and Plenipotentiary

Ruler. When she married Haakon,

in 1363, he was yet co-King of Sweden, making Margaret queen, and

despite being deposed, they never relinquished the title. When the

Swedes expelled Albert I in 1389, in theory, Margaret simply resumed her original position.

Margaret was born in Vordingborg Castle, the daughter of Valdemar IV of Denmark and Helvig of Schleswig. She married, at the age of ten, King Haakon VI of Norway, who was the younger and only surviving son to Magnus VII of Norway, Magnus II of Sweden.

Her first act after her father's death in (1375) was to procure the election of her infant son Olaf as king of Denmark, despite the claims of her elder sister's husband Duke Henry of Mecklenburg and their son. She insisted that he be proclaimed rightful heir of Sweden among his other titles. Olaf was too young to rule in his own right and Margaret proved herself a competent and shrewd ruler in the years that followed. In 1380, on the death of his father, Olaf succeeded his father as King of Norway. Young Olaf died rather suddenly at age 17. The following year Margaret, who had ruled both kingdoms in his name, was chosen Regent of Norway and Denmark. She had already proved her superior statesmanship by recovering possession of Schleswig from the Holstein Counts. The Counts had held it absolutely for more than a generation and received it back as a gift by the compact of Nyborg, but under such stringent conditions that the Danish Crown got all the advantage of the arrangement. By this compact, moreover, the chronically rebellious Jutish Nobility lost the support they had hitherto always found in Schleswig - Holstein. Margaret, free from all fear of domestic sedition, could now give her undivided attention to Sweden, where the mutinous nobles were already in arms against their unpopular King, Albert of Mecklenburg. Several of the powerful nobles wrote to Margrethe advising her that, if she would help rid Sweden of King Albert, she would become Regent. She lost no time gathering an army and invading Sweden.

At a conference held at Dalaborg Castle, in March 1388, the Swedes were compelled to accept all of Margaret's conditions, elected her "Sovereign Lady and Ruler," and engaged to accept from her any King she chose to appoint. On 24 February 1389, Albert, who had returned from Mecklenburg with an army of mercenaries, was routed and taken prisoner at Aasle near Falköping, and Margaret was now the omnipotent mistress of three kingdoms.

Stockholm,

then almost entirely a German city, still held out; fear of Margaret

induced both the Mecklenburg Princes and the Wendish towns to hasten to

its assistance; and the Baltic and the North Sea speedily swarmed with

the privateers of the Victual Brothers or Vitalian Brotherhood, so-called because their professed object was to revictual Stockholm. Finally the Hansa intervened,

and by the compact of Lindholm (1395) Albrecht was released by Margaret

on promising to pay 60,000 marks within three years. The Hansa in the

meantime were to hold Stockholm in pawn. Albert failed to pay his ransom

within the stipulated time; the Hansa surrendered Stockholm to Margaret

in September 1398, in exchange for commercial privileges.

It had been understood that Margaret should, at the first convenient opportunity, provide the three kingdoms with a King who was to be a kinsman of all the three old dynasties. However, in Norway it was specified that she would continue ruling alongside the new King. In 1389, she proclaimed her great - nephew, Eric of Pomerania (grandson of Henry of Mecklenburg), king of Norway, having adopted him and his sister Catherine. In 1396, homage was rendered to him in Denmark and Sweden; likewise, Margaret reserved to herself the office of Regent during his minority. To weld the united kingdoms still more closely together, Margaret summoned a Congress of the three Councils of the Realm to Kalmar in June 1397; and on Trinity Sunday, on 17 June, Eric was solemnly crowned King of Denmark, Norway and Sweden. The proposed Act of Union divided the three Councils, but the actual deed embodying the terms of the union never got beyond the stage of an unratified draft. Margaret balked at the clauses which insisted that each country should retain exclusive possession of its own laws and customs and be administered by its own dignitaries, because in her opinion this prevented the complete amalgamation of Scandinavia. But with her usual prudence, she avoided every appearance of an open rupture.

A few years after the Kalmar Union,

Eric, when in his eighteenth year, was declared of age and homage was

rendered to him in all his three kingdoms, but during her lifetime

Margaret was the real ruler of Scandinavia.

So long as the union was insecure, Margaret had tolerated the presence near the throne of "good men" from all three realms (the Rigsraad, or council of state, as these councilors now began to be called); but their influence was always insignificant. In every direction, the Royal authority remained supreme. The offices of High Constable and Earl Marshal were left vacant; the Danehofer or national assemblies fell into ruin, and the great Queen, an ideal despot, ruled through her court officials acting as superior clerks. But law and order were well maintained; the license of the nobility was sternly repressed; the Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway were treated as integral parts of the Danish State, and national aspirations were frowned upon or checked, though Norway, being more loyal, was treated more indulgently than Sweden.

Margaret also recovered for the Crown all the landed property which had been alienated during the troubled days before Valdemar IV. This so-called "reduktion" or land recovery, was carried out with the utmost rigor, and hundreds of estates fell into the hands of the Crown.

Margaret also reformed the Danish currency, substituting good silver coins for the old and worthless copper tokens, to the great advantage both of herself and the state. She had always large sums of money to dispose of, and a considerable proportion of this treasure was dispensed in works of charity.

Margaret's foreign policy was sagaciously circumspect, in sharp contrast with the venturesomeness of her father's. The most tempting offer of alliance, the most favorable conjunctures, could never move her from her system of neutrality. On the other hand she spared no pains to recover lost Danish territory. She purchased the island of Gotland from its actual possessors, Albert of Mecklenburg and the Livonian Order, and the greater part of Schleswig was regained in the same way.

In 1402, Queen Margaret entered into negotiations with the King of England, Henry IV about the possibility of a double - wedding alliance between England and the Nordic Union. The proposal was for a double - wedding, whereby King Eric would marry King Henry's daughter, Philippa, and King Henry's son, the Prince of Wales and future King Henry V would marry King Eric's sister, Catherine. The English side wanted these weddings to seal an offensive alliance between the Nordic Kingdoms and England, which could have led to the involvement of the Nordic union on the English side in the ongoing Hundred Years' War against France. Queen Margaret led a consistent foreign policy of not getting entangled in binding alliances and foreign wars. She therefore rejected the English proposals. The double - wedding did not come off, but Eric's wedding to Philippa was successfully negotiated. On 26 October 1406, King Eric married the 13 year old Philippa, daughter of Henry IV of England and Mary de Bohun, at Lund. The wedding was accompanied by a purely defensive alliance with England. For Eric's sister Catherine, a wedding was arranged with John, Count Palatine of Neumarkt. Margaret thus acquired a southern German ally, who could be useful as a counterweight to the northern German Princes and cities.

Margaret died suddenly on board her ship in Flensburg Harbor on 28 October 1412. Her sarcophagus made by the Lübeck sculptor Johannes Junge (1423) stands behind the high altar in the Roskilde Cathedral, near Copenhagen. She had left property to the Cathedral on the condition that Masses for her soul would be said regularly in the future. At the Reformation (1536) this was discontinued; however, to this day, a special bell is being rung twice daily in commemoration of the Queen.