<Back to Index>

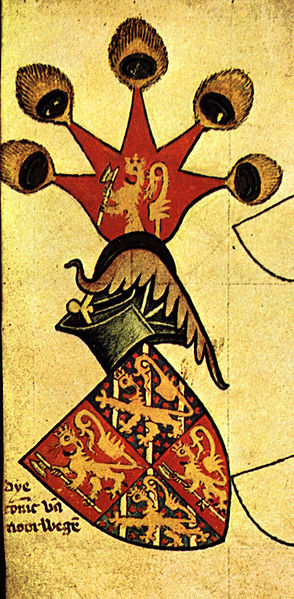

- King of Norway and Sweden Håkon VI Magnusson, 1340

PAGE SPONSOR

Haakon VI of Norway (English exonym: Hacon; Norwegian: Håkon 6 Magnusson; Swedish: Håkan Magnusson; circa 1340 – 1380) was King of Norway from 1343 until his death and King of Sweden from 1362 until 1364, when he was deposed by Albert of Mecklenburg in Sweden.

Haakon was born in 1340 in Sweden, the exact date and location of his birth is unknown; he died late during the summer in 1380 in Oslo where he was buried in St Mary's Church. He was the youngest son of Magnus Eriksson of Sweden and Blanche of Namur. His older brother, Eric Magnusson was King of Sweden until he died and Haakon succeeded him, although his rule over Sweden was brief.

Haakon married Margaret of Denmark, daughter of King Valdemar IV of Denmark. This was a political marriage intended to strengthen a long time dispute and peace with Denmark. They had a son together, named Oluf Haakonsson, who under Margaret I of Denmark would become a tool to initiate the over 400 year long union between Norway and Denmark.

Haakon

VI was a Norwegian king for 25 years and a Swedish king for 2 years; as

his father before him, he struggled to enforce and legitimize the rule

of the royal House of Bjelbo (Norwegian: Folkungeregimet) in Sweden. During his reign as king he witnessed the rise and growing of the powerful Hanseatic League,

which would eventually have a strong influence in Norwegian affairs and

politics. As he was the last king and ruler of an independent kingdom of Norway, he is considered the last true Norwegian king of old.

During the autumn of 1343 a large gathering of powerful members of the Norwegian state council met with King Magnus Eriksson at Varberg Castle. On August 15 the council declared that they and the king had agreed that the youngest son of the king should be made King of Norway. Hardly a year later, members of the cities and towns gathered at Bohus Castle. There Haakon was hailed as king and perpetual fealty and assistance was sworn to him.

The

meeting at Bohus Castle created new bonds to the old line of Kings of

Norway. The letter, created by the members of the Norwegian state

council, indicated that Haakon was to rule over only a part of Norway.

It also said that if Haakon was to die without a legitimate son the

common laws of succession to the closest blood related was to apply. The

true successor would then be his older brother, Eric Magnusson and his

bloodline would inherit the throne again in turn. The agreements of the

meetings in 1343 and 1344 were properly ratified in a meeting in Bergen in 1350.

Haakon took over as king between 8/18 August 1355, but during the following years it was mostly his father who would continue to rule the kingdom, although not in name anymore. The first time Haakon acted as sole king and ruler was in 22 January 1358, when he sent a letter with renewal of the privileges for the city of Oslo.

Haakon

was pulled into his fathers strife with and within Sweden, where a

conflict centering on Haakon's brother, Eric Magnusson. With Eric as a

gathering point, several powerful nobles helped him conduct a rebellion

against his father. Father and son made their peace the year after, but

the situation changed dramatically when Eric suddenly died in 1359. King

Magnus was subsequently deposed and with accordance to the agreements

of 1357, Haakon was elected king and was hailed in Uppsala 15 February 1362. From 1357 he styled himself as "Fyrste of Sweden" (English: Prince of Sweden) (German: Fürst von Schweden), and later he would style himself as "King of Norway and Sweden".

As a part of an agreement with King Valdemar IV of Denmark,

Haakon was betrothed to the Danish king's six year old daughter,

Margrete. Problems with the two kingdoms international politics put the

marriage on hold for a while, but after a hard and turbulent time with

various alliances, the two parts reconciled, and Haakon and Margrete

could host their wedding in 1363 at Copenhagen Cathedral.

The bond which was now created, was to create several dire consequences

for the two kingdoms and would shape the Nordic part of the world for

many hundreds of years.

In Sweden, new conflicts were brewing once again. Swedish noblemen had contacted Albert II, Duke of Mecklenburg who was married to King Magnus' sister, Euphemia of Sweden. They arranged for their son, Albert to become King of Sweden, and in November 1365 he was hailed as the Swedish king. From then on, the strife for Sweden would stand between the royal House of Bjelbo and the ducal House of Mecklenburg - Schwerin. In the first round, the House of Bjelbo lost to their ducal foes and their supporters. In the Battle at Gata (slaget ved Gata i Värmland) in Värmland, Haakon and Magnus suffered a decisive loss and Magnus was taken prisoner, and would remain a prisoner for six years.

The main goal for Haakon was now to win back Sweden. He still held possessions and ruled western parts of Sweden and could count on the support from several noblemen who was displeased with Albert of Sweden. After a successful campaign into Sweden and in the Battle of Stockholm in 1371 it looked like Haakon could turn the tide of the war and have his revenge for the loss at Gata; but Albert managed to withstand Haakon and in the peace treaty which was signed on 14 August 1371, Haakon had to be satisfied with freeing his father against a large ransom. King Magnus resumed his part as ruler over his possessions in Norway and Sweden, but died in 1374. Haakon had now added all his fathers possessions under himself again, and they were vast and helpful to him.

The

marriage between Haakon and Margrete created a new way of conducting

Norway's international politics. The Norwegian interests had to be

coordinated alongside with those of Denmark, and that was very hard and

problematic, this was mainly because of the northern cities and

principalities in Germany. These cities, with the city of Lübeck in front protested. In 1365 and 1366 rose a vicious strife in the city of Bergen, and the German office on Bryggen in

Bergen had to close down for a period. There was a far larger deal and

important interests for both the parties which was at stake during this

strife, and in 1368 the two parties gathered and agreed to form peace

between themselves. In a meeting at Bohus Castle in June 1370 a treaty was signed between the kingdom and the Hanseatic League which established a peace for 5 years.

In 1375 King Valdemar IV of Denmark died, and this spawned another strife between the two quarreling dynasties. King Valdemar had two daughters - Ingeborg, who was married to the powerful Henry III of Mecklenburg (who was the brother to King Albert of Sweden), and Magrete, married to King Haakon of Norway. Both parties instantly claimed to be the successor to the Danish throne. The Mecklenburgs claimed their own son, Albert, as rightful heir; but Haakon and Magrete claimed their own son as the only legitimate heir to the deceased Danish king. On 3 May 1376 Oluf Haakonsson was elected King of Denmark and so King Haakon and Magrete claimed the victory.

The Hanseatic League had

gained themselves the right to intervene in the Danish king election,

but they kept themselves neutral, this was because of King Haakon, as he

had paid them well for doing so. At the final peace settlement in 1376

the Hanseatic League managed to confirm "all their old rights, as freely

as they had ever used them" within the two kingdoms. This greatly

contributed to the vast growing of power within the league.

In 1379 Haakon solved the disputes over succession in the Norse earldom of Orkney, awarding it to Henry Sinclair, ocean explorer, a (youngest) grandson of earl Maol Íosa V, Earl of Strathearn, over the widower of Maol Iosa's elder daughter and other descendants.

After

King Haakon's father's death, he left Haakon a vast portion of Swedish

lands. Haakon was never satisfied with the lands he had inherited, he

wanted all of Sweden under him, and it would become a lifelong quest for

him to unite Sweden under the House of Bjelbo. In March 1380 he wrote a letter which was to "all the men in Sogn", the letter requested that the leidang fleet should be assembled and made ready for departure. The reason for this was "because the Germans in

Sweden" had broken the treaty of peace and prepared for war against

him. There was no war or battles fought, and Haakon neared his final

days. He died after the summer the same year, only 40 years old, and he was buried in his own church.

King Haakon inherited a kingdom ravaged by the Black Plague. In 1349, the Black Death was brought to Norway arriving first in the port of Bergen. It is estimated that as much as half of the population had died during the first plague and new plagues followed in 1360 and 1370 - 71. The financial situation, which was originally weak, was weakened even further as the plague ravaged; and at the same time, the international politics of Norway required vast sums of money.

The ransom King Haakon had to pay for his father in 1371 was around 12 000 silver marks, that was alone larger than the ordinary Norwegian tax incomes just before the Black Plague. King Haakon was dependent on foreign help, and he took up vast loans from the city of Lübeck, who knew just how to take advantage of this crisis to their own advantage.

The Norwegian nobility stood weakened as well after the Black Plague, both politically and financially. This made it utterly necessary for cooperation between the rich, the nobles and the king. The state council, which hosted most of the clergy and secular lords as members, was regularly convened. Even more Swedish noblemen came to Norway during the reign of King Haakon and established themselves there.

King Haakon had also with the church as an institution, an unproblematic cooperation, and it appears that the requirement of ecclesiastical jurisdiction in Christian trials generally was respected.