<Back to Index>

- King of Norway, Denmark and Sweden Eirik III of Pomerania, 1381

PAGE SPONSOR

Eric of Pomerania KG (1381 or 1382 – 3 May 1459) was King Eric III of Norway (1389 – 1442) Norwegian Eirik, King Eric VII of Denmark (1396 – 1439), and as Eric (Ericus) King of Sweden (1396 – 1439; known there in history mainly as Erik av Pommern). He was the first King of the Nordic Kalmar Union, succeeding his adoptive mother Margaret I of Denmark.

Referring to Eric of Pomerania as King Eric XIII of Sweden is a later invention, counting backwards from Eric XIV (1560 – 68). He and his brother Charles IX (1604 – 1611)

adopted numerals according to a fictitious history of Sweden. The

number of Swedish monarchs named Eric before Eric XIV (at least seven)

is unknown, going back into prehistory, and none of them used numerals. It would be speculative to try to affix a mathematically accurate one to this king.

Eric was a son of Wartislaw VII, Duke of Pomerania, and Mary of Mecklenburg - Schwerin. His paternal grandparents were Boguslaw V, Duke of Pomerania and his second wife Adelheid of Brunswick - Grubenhagen. His maternal grandparents were Heinrich III of Mecklenburg - Schwerin and Ingeborg of Denmark, Duchess of Mecklenburg - Schwerin. Heinrich was a rival of Olaf Haakonsson in regard to the Danish succession in 1375.

Ingeborg was a daughter of Valdemar IV of Denmark and his Queen consort Heilwig of Schleswig. Her maternal grandparents were Eric II, Duke of Schleswig (reigned 1312 – 1325) and Adelheid of Holstein - Rendsburg.

Eric was born in 1382 in Rügenwalde (Darłowo). Initially named Boguslaw, he was son to the only surviving granddaughter of Valdemar IV of Denmark and also a descendant of Magnus III of Sweden and Haakon V of Norway.

On 2 August 1387, Olav Håkonsson, King of Denmark since he was five years old and King of Norway since the death of his father, died unexpectedly at seventeen years of age. His mother the Dowager Queen of Norway had added the phrase "the true heir of Sweden" to Boguslaw's list of titles at his coronation. Boguslaw's claim to the Swedish throne came through his great - granduncle, Magnus IV of Sweden, who was forced to abdicate by the Swedish nobles. After the abdication, the Swedish nobles, led by Bo Jonsson (Grip), had invited Count Albert of Mecklenburg to take the Swedish throne. However, when Albert attempted to introduce reduction of their large estates, they quickly turned against him. The nobles, including his former supporter Bo Jonsson Grip, Sweden's largest landowner who controlled a third of the entirety of the Swedish territory and had the largest non - royal wealth in the country, soon conspired to get rid of him, resenting his attempts to restrict the traditional privileges of the nobility, as well as his use of German officials to fill important administrative positions in the Swedish provinces.

The Rigsråd (Danish Thing) elected Queen Margaret as "all powerful lady and mistress and the Kingdom of Denmark's Regent". Just a year later, the Norwegians proclaimed Margaret the "reigning queen" and Albert of Sweden fought off an incursion from Norway. His respite was temporary — the Swedish nobility soon enlisted the Danish regent's help to remove Albert from the Swedish throne. In 1388, several of the Swedish nobles wrote secretly to Margaret telling her that if she could rid them of Albert, they would make her Regent. Margaret lost no time and sent an army into Sweden to attack Albert while the Swedish nobles raised their own army to drive him out of the country. In 1389, Albert's forces were defeated at the Battle of Falköping in Västergötland. Albert and his son Erik were captured when their horses became mired in mud so deep they could not escape. They were put into chains and sent by Queen Margaret to Scania, where Albert was imprisoned in Lindholmen Castle. It took until 1395 for Margaret to force Albert's supporters out of Stockholm. She made provisions for the three kingdoms in the event of her death. She wanted the kingdoms to be unified and peaceful and hence, chose the son of her father's surviving granddaughter, Boguslaw, to be named heir.

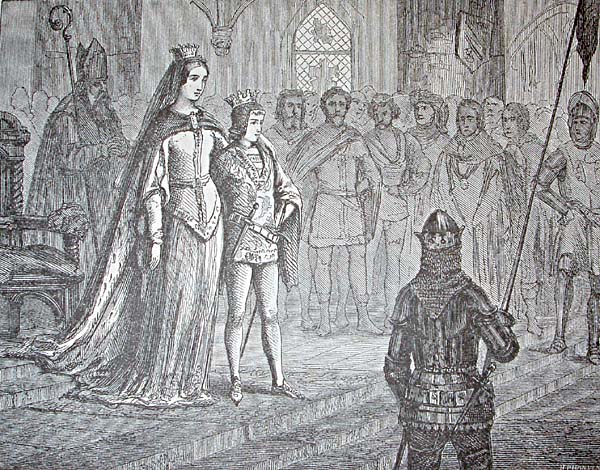

Young

Boguslaw was the grandson of Margaret's sister. In 1389 he was brought

to Denmark to be brought up by Queen Margaret. His name was changed to

the more Nordic sounding Erik. On 8 September 1389, he was hailed as King of Norway at the Ting in Trondheim. He may have been crowned King of Norway in Oslo in

1392, but this is disputed. In 1396 he was proclaimed as king in

Denmark and then in Sweden. On 17 June 1397, he was crowned a king of

the three Nordic countries in the cathedral of Kalmar. At the same time, a union treaty was drafted, declaring the establishment of what has become known as the Kalmar Union. Queen Margaret, however, remained the de facto ruler of the three kingdoms until her death in 1412.

In 1402, Queen Margaret entered into negotiations with King Henry IV of England about the possibility of an alliance between the Kingdom of England and the Nordic union. The proposal was for a double wedding, whereby Eric would marry Henry's daughter, Philippa, and Henry's son, the Prince of Wales and future King Henry V, would marry Eric's sister,Catherine.

The English side wanted these weddings to seal an offensive alliance between the Nordic kingdoms and England, which could have led to the involvement of the Nordic union on the English side in the ongoing Hundred Years' War against the Kingdom of France. Queen Margaret led a consistent foreign policy of not getting entangled in binding alliances and foreign wars. She therefore rejected the English proposals.

The

double wedding did not come off, but Eric's wedding to Philippa was

successfully negotiated. On 26 October 1406, Eric married the

13 year old Philippa at Lund. The wedding was accompanied by a purely defensive alliance with England.

From contemporary sources, Eric appears as intelligent, visionary, energetic and a firm character. That he was also a charming and well spoken man of the world was shown by a great European tour of the 1420s. Negatively, he seems to have had a hot temper, a lack of diplomatic sense, and an obstinacy that bordered on mulishness.

Almost the whole of Eric’s sole rule was affected by his long standing conflict with the Counts of Schauenburg and Holstein. He tried to regain South Jutland (Schleswig) which Margaret had been winning but he chose a policy of warfare instead of negotiations. The result was a devastating war that not only ended without conquests but also led to the loss of the South Jutlandic areas that he had already obtained. During this war he showed much energy and steadiness, but also a remarkable lack of adroitness. In 1424, a verdict of the Holy Roman Empire by Sigismund, King of Germany, recognizing Eric as the legal ruler of South Jutland, was ignored by the Holsteiners. The long war was a strain on the Danish economy as well as on the unity of the north.

Perhaps Eric's most far-ranging act was the introduction of the Sound Dues (Øresundtolden) in 1429, which was to last until 1857. By this he secured a large stable income for his kingdom that made it relatively rich and which made the town of Elsinore flowering. It showed his interest in Danish trade and naval power, but also permanently challenged the other Baltic powers, especially the Hanseatic cities against which he also fought. Another important event was his making Copenhagen a royal possession in 1417, thereby assuring its status as the capital of Denmark.

During the 1430s the policy of the king fell apart. In 1434 the farmers and mine workers of Sweden began a national and social rebellion which was soon used by the Swedish nobility in order to weaken the power of the king. He had to yield to the demands of both the Holsteiners and the Hanseatic League. In Norway, a peasant rebellion led by Amund Sigurdsson (1400 – 1465), rebelled against King Erik and his officials, besieging Oslo and Akershus Castle. When the Danish nobility opposed his rule and refused to ratify his choice of Bogislaw IX, Duke of Pomerania as the next King of Denmark, he left Denmark and settled at his castle Visborg in Gotland, apparently a kind of a “royal strike” which led to his deposition by the National Councils of Denmark and Sweden in 1439. The Norwegian nobility remained loyal to King Erik, and in 1439 he gave Sigurd Jonsson the title of drottsete, under which he was to rule Norway in King Erik's name. But with the King isolated in Gotland, the Norwegian nobility also felt compelled to depose him in 1440.

For

ten years Erik lived on Gotland and made his living by piracy against

the merchant trade in the Baltic. Eventually he returned to Pomerania,

where he died in 1459.

In 1440, Eric, having been deposed in Denmark and Sweden, was succeeded by his nephew, Christopher of Bavaria, who had been chosen for the thrones. After he had been deposed as king in Sweden and Denmark, the Norwegian Riksråd remained loyal to him, and wanted him to remain king of Norway only. He reputedly refused the offer. Christopher, his successor, died in 1448, long before Eric himself.

The next monarch (reigned 1448 – 81) was Eric's kinsman, Christian I of Denmark, who was the son of Eric's earlier rival, Count Theodoric of Oldenburg. To him Eric handed over Gotland in return for the permission to leave for Pomerania.

From

1449 – 59, Eric succeeded Bogislaw IX, as Duke of Pomerania and ruled

Pomerania - Rügenwalde, a small partition of the Duchy of Pomerania - Stolp (Polish: Księstwo Słupskie), as Eric I. He died in 1459 at Darłowo (German: Rügenwalde) Castle and is buried in Church of St. Mary's in Darłowo in Pomerania.