<Back to Index>

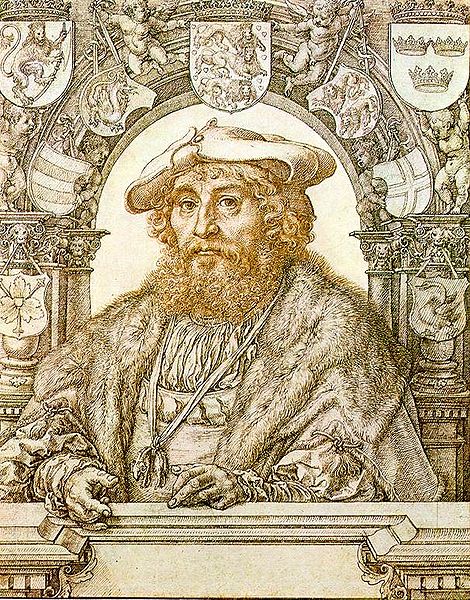

- King of Denmark, Norway and Sweden Christian II, 1481

PAGE SPONSOR

Christian II (1 July 1481 – 25 January 1559) was King of Denmark, Norway (1513 – 23) and Sweden (1520 – 21), during the Kalmar Union.

Christian was born as the son of King John of Denmark and Christina of Saxony, at Nyborg Castle in 1481 and succeeded his father as king and regent in Denmark and Norway, where he later was to be succeeded by his uncle King Frederick I of Denmark.

Christian descended, through both Valdemar I of Sweden and Magnus I of Sweden, from the Swedish Dynasty of Eric, and from Catherine, daughter of Inge I of Sweden, as well as from Ingrid Ylva, granddaughter of Sverker I of Sweden. His rival Gustav I of Sweden descended only from Sverker II of Sweden and the Dynasty of Sverker (who apparently did not descend from ancient Swedish kings).

Christian took part in his father John of Denmark's conquest of Sweden in 1497 and in the fighting of 1501 when Sweden revolted. He was appointed viceroy of Norway in 1506, and succeeded in maintaining control of this country. During his administration in Norway, he attempted to deprive the Norwegian nobility of its traditional influence exercised through the Rigsraadet privy council, leading to controversy with the latter.

Christian's succession to the throne was confirmed at the Herredag assembly of notables from the three northern kingdoms, which met at Copenhagen in 1513. The Swedish delegates said, "We have the choice between peace at home and strife here, or peace here and civil war at home, and we prefer the former." A decision as to the Swedish succession was therefore postponed.

During

his reign, Christian concentrated on his attempts to maintain control

of Sweden while attempting a concentration of power in the hands of the monarch, at the expense of both clergy and nobility. To further this attempt, he supported the creation of a strong class of burghers.

A peculiarity, more fatal to him in that aristocratic age than any other, was his fondness for the common people, which was increased by his passion for a pretty Norwegian girl of Dutch heritage, named Dyveke Sigbritsdatter, who became his mistress in 1507 or 1509. On 12 August 1515, Christian married Isabella of Austria, the granddaughter of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I. But he would not give up his liaison with Dyveke, and it was only her death in 1517, under suspicious circumstances, that prevented serious complications with the emperor Charles V.

Christian believed that the magnate Torben Oxe was guilty of Sigbritsdatter's death and, despite his having been acquitted of murder charges by Rigsraadet, had him executed. Oxe was brought to trial at Solbjerg outside Copenhagen in what amounted to a justice - of - the - peace court on vague offenses against his liege lord, Christian II. The verdict as directed by the king was guilty and the death sentence imposed with the comment, 'your deeds not your words have condemned you'. Over the strenuous opposition of Oxe's fellow peers he was executed at St. Clare's Hosptial Cemetery in late 1517. Thereafter the king lost no opportunity to suppress the nobility and raise commoners to power.

His chief councilor was Dyveke's mother Sigbrit Willoms, who excelled in administrative and commercial affairs. Christian first appointed her controller of the Sound Dues of Øresund,

and ultimately committed to her the whole charge of the finances. A

bourgeoise herself, it was Sigbrit's constant policy to elevate and

extend the influence of the middle classes. She soon formed a

middle class inner council centering on her, which competed for power

with Rigsraadet itself.

The patricians naturally resented their supercession and nearly every

unpopular measure was attributed to the influence of "the foul - mouthed

Dutch sorceress who hath bewitched the king." However, Mogens Gøye, the leading man of the Council, supported the king as long as possible.

Christian was meanwhile preparing for the inevitable war with Sweden, where the patriotic party, headed by the freely elected Viceroy Sten Sture the Younger, stood face to face with the pro - Danish party under Archbishop Gustav Trolle. Christian, who had already taken measures to isolate Sweden politically, hastened to the relief of the archbishop, who was beleaguered in his fortress of Stäket, but was defeated by Sture and his peasant levies at Vedila and forced to return to Denmark. A second attempt to subdue Sweden in 1518 was also frustrated by Sture's victory at Brännkyrka.

A third attempt made in 1520 with a large army of French, German and Scottish mercenaries proved successful. Sture was mortally wounded at the Battle of Bogesund, on 19 January, and the Danish army, unopposed, was approaching Uppsala, where the members of the Swedish Privy Council, or Riksråd, had already assembled. The councilors consented to render homage to Christian on condition that he gave a full indemnity for the past and a guarantee that Sweden should be ruled according to Swedish laws and custom; and a convention to this effect was confirmed by the king and the Danish Privy Council on 31 March.

Sture's widow, Dame Christina Gyllenstierna, still held out stoutly at Stockholm, and the peasantry of central Sweden, roused by her patriotism, flew to arms, defeated the Danish invaders at Balundsås on 19 March, and were only with the utmost difficulty finally defeated at the bloody battle of Uppsala, on Good Friday,

6 April 1520. In May the Danish fleet arrived, and Stockholm was

invested by land and sea; but Dame Gyllenstierna resisted valiantly for

four months longer and took care, when she surrendered on 7 September,

to exact beforehand an amnesty of the most explicit and absolute

character. On 1 November, the representatives of the nation swore fealty

to Christian as hereditary king of Sweden, though the law of the land distinctly provided that the Swedish crown should be an elective monarchy.

On 4 November, Christian was anointed by Gustav Trolle in Stockholm Cathedral, and took the usual oath to rule the Realm of Sweden through native born Swedes alone, according to prescription. The next three days were given up to banqueting, but on 7 November "an entertainment of another sort began." On the evening of that day Christian summoned his captains to a private conference at the palace, the result of which was quickly apparent, for at dusk a band of Danish soldiers, with lanterns and torches, broke into the great hall and carried off several carefully selected persons.

By 10 o'clock the same evening the remainder of the king's guests were safely under lock and key. All these persons had previously been marked down on Archbishop Trolle's proscription list. On the following day a council, presided over by Trolle, solemnly pronounced judgment of death on the proscribed, as manifest heretics. At 12 o'clock that night the patriotic bishops of Skara and Strängnäs were led out into the great square and beheaded. Fourteen noblemen, three burgomasters, fourteen town councilors and about twenty common citizens of Stockholm were then drowned or decapitated. The executions continued throughout the following day; in all, about eighty - two people are said to have been murdered.

Moreover, Christian ordered that Sten Sture's

body should be dug up and burnt, as well as the body of his little

child. Dame Christina and many other noble Swedish ladies were sent as

prisoners to Denmark. When it became necessary to make excuses for the

massacre, Christian proclaimed to the Swedish people that it was a

measure necessary to avoid a papal interdict, while in his apology to

the pope for the decapitation of the innocent bishops he described it as

an unauthorized act of vengeance on the part of his own people. The massacre and deeds in the Old Town of Stockholm is the primary reason why Christian is remembered in Sweden, as Christian the Tyrant (Kristian Tyrann).

Christian II returned to his native kingdom of Denmark, his brain teeming with great designs. There can be no doubt that the welfare of his dominions was dear to him. Inhuman as he could be in his wrath, in principle he was as much a humanist as any of his most enlightened contemporaries. But he would do things his own way; and deeply distrusting the Danish nobles with whom he shared his powers, he sought help from the wealthy and practical middle classes of Flanders. In June 1521, he paid a sudden visit to the Low Countries, and remained there for some months. He visited most of the large cities, took into his service many Flemish artisans, and made the personal acquaintance of Quentin Matsys and Albrecht Dürer; the latter painted his portrait. Christian also entertained Erasmus, with whom he discussed the Protestant Reformation, and let fall the characteristic expression: "Mild measures are of no use; the remedies that give the whole body a good shaking are the best and surest."

Never

had King Christian seemed so powerful as upon his return to Denmark on 5

September 1521, and, with the confidence of strength, he at once

proceeded recklessly to inaugurate the most sweeping reforms. Soon after

his return he issued his great Landelove, or Code of Laws. For the most

part this is founded on Dutch models, and testifies in a high degree to

the king's progressive aims. Provision was made for the better

education of the lower, and the restriction of the political influence

of the higher clergy; there were stern prohibitions against wreckers and

"the evil and unchristian practice of selling peasants as if they were

brute beasts"; the old trade guilds were retained, but the rules of

admittance thereto made easier, and trade combinations of the richer

burghers, to the detriment of the smaller tradesmen, were sternly

forbidden.

Unfortunately these reforms, excellent in themselves, suggested the standpoint not of an elected ruler, but of a monarch by divine right. Some of them were even in direct contravention of the charter; and the old Scandinavian spirit of independence was deeply wounded by the preference given to the Dutch. Sweden, too, was now in open revolt; and both Norway and Denmark were taxed to the utmost to raise an army for the subjection of their sister kingdom. Foreign complications were now added to these domestic troubles. With the laudable objective of releasing Danish trade from the grinding yoke of the Hanseatic League, and making Copenhagen the great emporium of the north, Christian had arbitrarily raised the Sound tolls and seized a number of Dutch ships that presumed to evade the tax. Thus, his relations with the Netherlands were strained, while he was openly at war with Lübeck and her allies.

Jutland finally rose against him, renounced its allegiance, and offered the Danish crown to Christian's uncle, Duke Frederick of Holstein, 20 January 1523. So overwhelming did Christian's difficulties appear that he took ship to seek help abroad, and on 1 May landed at Veere in Zeeland. During the years of his exile, the king led a relatively humble life in the city of Lier in the Netherlands, waiting for the military help of his reluctant imperial brother - in - law. In the meantime, he became regarded a social savior in Denmark, where both the peasants and the commoners began to wish for his restoration. He found consolation in his distress to enter in connection with Martin Luther and for some time, he even became a Lutheran. Christian and his wife lived next Lier, in Brabant, where Elizabeth died in January 1526, after which the children were taken away from Christian to not be raised as heretics. But when both his opponent, Frederick I, and Gustav Vasa, who joined the Reformation, became Lutherans in 1530 Christian reconverted to Roman Catholic Church and thus reconciled with the Emperor. Eight years later, on 24 October 1531, he attempted to recover his kingdoms, but a tempest scattered his fleet off the Norwegian coast, and on 1 July 1532, by the convention of Oslo, he surrendered to his rival, King Frederick, in exchange for a promise of safe conduct.

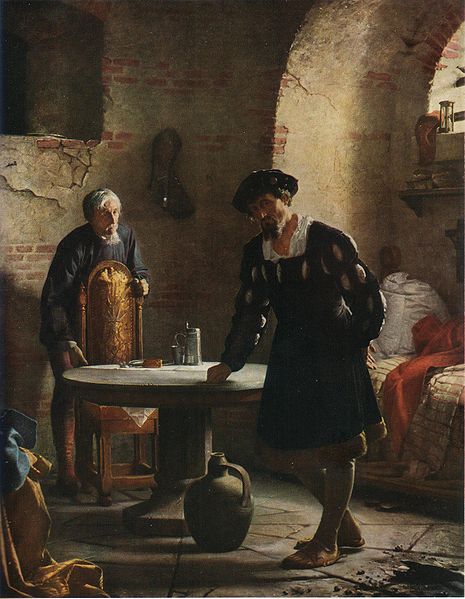

But King Frederick did not keep his promise, and King Christian was kept prisoner for the next 27 years, first in Sønderborg Castle until 1549, and afterwards at the castle of Kalundborg.

Stories of solitary confinement in small dark chambers are inaccurate;

King Christian was treated like a nobleman, particularly in his old age,

and he was allowed to host parties, go hunting, and wander freely as

long as he did not go beyond the boundaries of the town of Kalundborg. His cousin, King Christian III of Denmark,

son of Frederick I, died in early 1559, and it was said that even then,

with the old king nearing 80, people in Copenhagen looked warily

towards Kalundborg. But King Christian II died peacefully just a few

days later, and the new king, Frederick II, ordered that a royal funeral be held in memory of his unhappy kinsman, who lies buried in Odense next to his wife, son and parents.

Christian II is one of the most discussed of all Danish kings. He has been regarded as both a hypocritical tyrant and a progressive despot, who wanted to create an absolute monarchy based upon “free citizens”. His psychological weaknesses have caught the interest of historians, especially his frequently mentioned irresolution, which as years passed seemed to dominate his acts. Theories of manic depression have been mentioned, but like many others they are impossible to prove. The reasons for his downfall were probably that he made too many enemies and that the Danish middle class was still not strong enough to make up a base of royal power. However some of his ambitions were fulfilled by the victory of absolutism in 1660.

The king’s life and career have created many myths. One of the most famous is the story of the irresolute king crossing the Little Belt forwards

and backwards during a whole night in February 1523, until he at last

gave up. Another, probably just as unlikely, is the legend that the

restless king wandered around a round table on Sønderborg making a

groove in the table top with his finger. His life has also inspired

modern Danish poets and authors. In Johannes Vilhelm Jensen's novel The Fall of the King (1900 – 1901), the king is regarded almost as a symbol of the Danish “illness of hesitation”.

Among the six children of Christian II, three must be mentioned. Prince John died as a boy in exile in 1532. The two daughters Dorothea, Electress Palatine, and Christina, Duchess of Lorraine, both in turn, for many years, demanded in vain the Danish and Norwegian thrones as their inheritance. Christian II's blood returned to the Swedish and Norwegian thrones in the person of Charles XV of Sweden, descendant of Renata of Lorraine.

By his wife, Isabella of Austria (1501 – 1526) he had six children:

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| John | 21 February 1518 | 1532 | |

| Philip Ferdinand (twin) | 4 July 1519 | 1520 | |

| Maximilian (twin) | 4 July 1519 | 1519 | |

| Dorothea | 10 November 1520 | 31 May 1580 | married in 1535, Frederick II, Elector Palatine and had no issue. |

| Christina | c.1522 | c.1590 | married in 1533, Francis II Sforza and had no issue, married secondly in 1541, Francis I, Duke of Lorraine and had issue. |

| stillborn son | January 1523 | January 1523 |