<Back to Index>

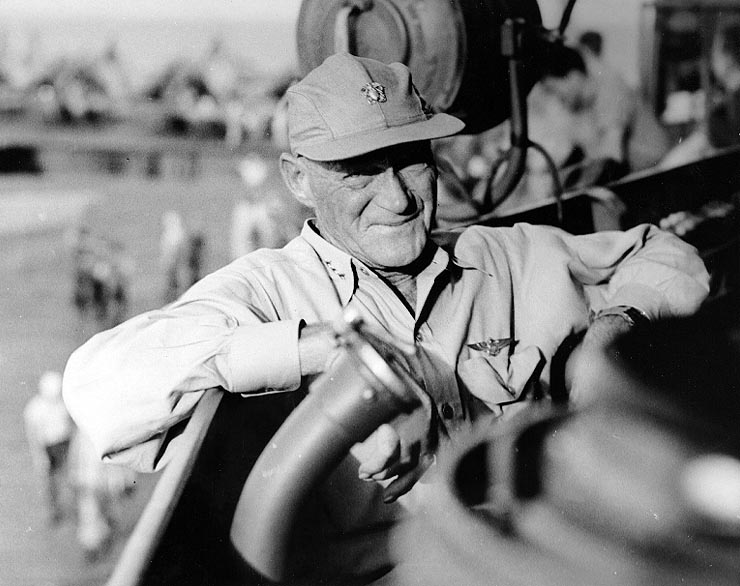

- Commander of Fast Carrier Task Force 58 of the United States 5th Fleet Admiral Marc Andrew "Pete" Mitscher, 1887

- Commander of the United States Pacific Fleet Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, 1885

PAGE SPONSOR

Admiral Marc Andrew "Pete" Mitscher (January 26, 1887 – February 3, 1947) was an admiral in the United States Navy who served as commander of the Fast Carrier Task Force in the Pacific in the latter half of World War II.

Marc Andrew "Pete" Mitscher was born in Hillsboro, Wisconsin, on January 26, 1887, the son of Oscar & Myrta (Shear) Mitscher. Mitscher's grandfather Andreas Mitscher (1821 – 1905) was a German immigrant from Traben - Trarbach. In 1854 Andreas married Constantina Moln who was also of German descent. During the western land boom of 1889, when Marc was two years old, his family resettled in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, where his father, a federal Indian Agent, later became that city's second mayor. Despite the family settlement in Oklahoma, records attest that Mitscher attended elementary and secondary schools in Washington, D.C. and received an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, in 1904 through Bird Segle McGuire, then U.S. Representative from Oklahoma. An indifferent student, Mitscher seemed to be in continuous trouble, earning 159 demerits in one class year. In 1906 he resigned, but his father immediately coaxed McGuire to reappoint him. After six years, in 1910 he graduated 113th out of 131 classmates and served at sea for two years (as required by law at that time) on board USS Colorado (ACR-7), becoming a commissioned Ensign on March 7, 1912. In August 1913 he served aboard the USS California (ACR-6) on the West Coast of the U.S. during the Mexican Campaign

Subsequent to duties on the destroyers USS Whipple (DD-15) and USS Stewart (DD-13), in September 1915 Mitscher reported for aviation training at Naval Aeronautic Station, Pensacola, Florida, on board the armored cruiser USS North Carolina (ACR-12), at that time one of the first ships in the U.S. Navy to carry an airplane. Mitscher was designated Naval Aviator No. 33 on June 2, 1916. Almost a year later, on April 6, 1917, he reported to the renamed armored cruiser USS Huntington (ACR-5) previously commissioned USS West Virginia (ACR-5), for duty in connection with aircraft catapult experiments. This duty was followed by command of NAS Dinner Key in Coconut Grove, Florida, by Lt. Mitscher. Dinner

Key was the second largest naval air facility in the U.S. and was used

to train seaplane pilots. On July 18, 1918 he was promoted to Lt.

Commander and in February 1919 he transferred from NAS Dinner Key to the

Aviation Section in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations before reporting to Seaplane Division 1.

On May 10, 1919 he took off from Newfoundland as the pilot of the NC-1, one of four Curtiss NC Flying Boat aircraft in the Naval Transatlantic flight expedition. His plane and the NC-3 landed in heavy fog near the Azores, but heavy seas prevented them from joining NC-4 in completing the first transatlantic air passage. For his part in this historic operation, Mitscher received the Navy Cross. The citation for his Navy Cross read as follows:

"For distinguished service in the line of his profession as a member of the crew of the Seaplane NC-1, which made a long overseas flight from New Foundland to the vicinity of the Azores, in May 1919".

In addition to several shore based commands, Mitscher, during the next two decades, served on the aircraft carriers Langley and Saratoga, the seaplane tender Wright, and as the Commander of Patrol Wing 1.

Lieut.

Marc A. Mitscher reported for duty aboard USS Aroostook (CM-3) on

October 14, 1919, serving under the Commanding Officer Captain Henry C.

Mustin. USS Aroostook was assigned temporary duties as flag ship for the

Air Detachment, Pacific Fleet. He was promoted to Lieut. Comdr. date of

rank July 1, 1921. In May 1922, Lieut. Comdr. Mitscher was detached

from Air Squadrons, Pacific Fleet (San Diego CA) to command Naval Air

Station Anacostia, D.C.

Between June 1939 and July 1941 he served as assistant chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics. Thereafter, he fitted out the carrier Hornet, and he assumed her command at her commissioning in October 1941. While under his command, the Hornet launched the Doolittle Raid against Japan in early 1942 and thus gained fame as to their point of origin being "Shangri La" expressed during a news conference given by President Roosevelt.

Mitscher captained her during the Battle of Midway 4 to June 6, but his air group's performance in that crucial engagement ranged from disappointing to outright disastrous. On the eve of the Battle of Midway, Admiral Mitscher, with the support of his Air Group Commander, CDR Stanhope C. Ring, denied fighter air cover to the Hornet's torpedo squadron, led by LCDR John C. Waldron. Mitscher then ordered the strike group to fly a course of 265 degrees true (instead of the 234 degrees of the enemies last sighting). This resulted in most of the air group never sighting the enemy. Waldron's Torpedo Eight squadron, because Waldron disobeyed orders and flew course 240 degrees, flew directly to the enemy carrier group's location. Torpedo Eight was the first carrier squadron to be in position to attack and, unescorted by fighters, was obliterated by Japanese Zeros. Only one man survived (Ens. George H.Gay Jr). However, Torpedo Eight's sacrifice enabled dive bombers from the carriers Enterprise and Yorktown to sink three Japanese carriers virtually unopposed. In spite of CDR Ring's hearing CDR Waldron's radioed report that he had found the enemy, CDR Ring continued on course 260 degrees to nowhere. The Hornet strike force following the orders of CDR Ring was unable to find the enemy, and eventually headed back toward either the Hornet, or Midway Island, to land and refuel. All ten fighters in the formation ran out of fuel and ditched at sea. Several dive bombers also had to ditch on their approach to the Midway base. Except for Torpedo Eight, none of the Hornet's strike force played any role on the first day of the Battle of Midway.

Mitscher was detached from the Hornet June 30, less than four months before her loss on October 26 during the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands.

Mitscher commanded Patrol Wing 2 until December when he became commander fleet air, Nouméa. In April 1943 he became commander air, Solomon Islands, and from August to January 1944 he commanded Fleet Air, West Coast. Returning to the central Pacific as Commander, Carrier Division 3, he was appointed Vice Admiral March 21, 1944 and ordered to take command of the Fast Carrier Task Force (then 5th Fleet's TF 58). With the Lexington as his flagship for this task force, which operated alternately as 3rd Fleet's TF 38, he inflicted severe and irreparable damage on Japanese ground installations and against enemy naval and merchant shipping. His hard hitting, wide ranging carriers pounded the enemy from Truk to the Palaus, along the New Guinea coast, and throughout the Marianas. His eager, resourceful aviators devastated Japanese carrier forces in the Battle of the Philippine Sea — also known as the Marianas Turkey Shoot — during June 1944. Notably, when a follow up strike was forced to return to his carriers in darkness, Mitscher earned the gratitude of his pilots by turning on the flight decks' running lights, defying standard naval procedure and ensuring that most of them were recovered.

During the next year his warring carriers spearheaded the thrust against the heart of the Japanese Empire, covering successively the invasion of the Palaus, the liberation of the Philippines, and the conquest of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. During these operations he repeatedly led the fast carriers northward to pound the Japanese home islands.

By

July 1946 when he returned to the United States to serve as Deputy

Chief of Naval Operations (Air), Mitscher had received, among other

awards, two Gold Stars in lieu of a second and third Navy Cross and the Distinguished Service Medal with two Gold Stars. He served briefly as commander 8th Fleet and on March 1, 1946 became Commander - in - Chief, U.S. Atlantic Fleet, with the rank of Admiral. While serving in that capacity, Mitscher died at Norfolk, Virginia, at the age of 60. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

The words of Admiral Arleigh Burke provide the greatest tribute and recognition of his leadership:

- "He spoke in a low voice and used few words. Yet, so great was his concern for his people — for their training and welfare in peacetime and their rescue in combat — that he was able to obtain their final ounce of effort and loyalty, without which he could not have become the preeminent carrier force commander in the world. A bulldog of a fighter, a strategist blessed with an uncanny ability to foresee his enemy's next move, and a lifelong searcher after truth and trout streams, he was above all else — perhaps above all other — a Naval Aviator."

Two ships of the Navy have been named USS Mitscher in his honor; the post - World War II frigate, USS Mitscher (DL-2) later re-designated as the guided missile destroyer (DDG-35), and the currently serving Arleigh Burke class guided missile destroyer, USS Mitscher (DDG-57).

In addition to the ships named after Admiral Mitscher, the airfield and a street at Marine Corps Air Station Miramar (Naval Air Station Miramar) have been named in his honor (Mitscher Field and Mitscher Way).

Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner (May 27, 1885 – February 12, 1961) served in the United States Navy during World War II.

Richmond Turner was born in Portland, Oregon, on May 27, 1885, to Enoch and Laura Francis (née Kelly) Turner. His father alternated between being a rancher and farmer, and working as a printer in both Portland (for The Oregonian with his older brother Thomas) and Stockton, California (where he owned a small print shop). Young Richmond would spend most of his childhood in and around Stockton, with a brief stop in Santa Ana, and graduating from Stockton High School in 1904.

He was appointed to the U.S. Naval Academy from California's sixth district, his name put forward by Congressman James Carion Needham, in 1904. He graduated on 5 June 1908 and served in several ships over the next four years.

On 3 August 1910, he married Harriet "Hattie" Sterling in Stockton.

In 1913, Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Turner briefly held command of the destroyer USS Stewart. After receiving instruction in ordnance engineering and service on board the gunboat Marietta, he was assigned to the battleships Pennsylvania, Michigan and Mississippi during 1916 - 19. From 1919 to 1922, Lieutenant Commander Turner was an Ordnance Officer at the Naval Gun Factory in Washington, D.C. He then was Gunnery Officer of the battleship California, Fleet Gunnery Officer on the Staff of Commander Scouting Fleet and Commanding Officer of the destroyer Mervine.

Following promotion to the rank of Commander in 1925, Turner served with the Bureau of Ordnance at the Navy Department. In 1927, he received flight training at Pensacola, Florida, and a year later became Commanding Officer of the seaplane tender Jason and Commander Aircraft Squadrons, Asiatic Fleet. He had further aviation related assignments into the 1930s and was Executive Officer of the aircraft carrier Saratoga in 1933 - 34. Captain Turner attended the Naval War College and served on that institution's staff in 1935 - 38 as head of the Strategy faculty.

Turner's final field command was the heavy cruiser Astoria, a diplomatic mission to Japan in 1939.

Turner was Director of War Plans in Washington, D.C., in 1940 - 41 and was promoted to Rear Admiral late in 1941.

As head of the War Plans Division of the Navy Department, Turner was subordinate only to the Chief of naval Operations, Admiral Harold R. Stark, at the time of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. Although in theory the Head of Naval Intelligence, Captain Theodore Wilkinson, reported directly to Stark, in practice he was answerable to Turner, and Turner made the important decisions about the handling of naval intelligence. It was therefore Turner who made the decision not to send the Commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, details of the intercepted Japanese diplomatic communications which pointed strongly to an imminent air or sea attack on the Pacific Fleet's base at Pearl Harbor. Kimmel testified after the war that had he known of these communications, he would have maintained a much higher level of alert and that the Fleet would not have been taken by surprise by the Japanese attack. The leading historian of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Professor Gordon Prange, wrote in Pearl Harbor: The Verdict of History that, even allowing for Kimmel's desire to exculpate himself, this was correct. Prange wrote: "If Turner thought a Japanese raid on Hawaii... to be a 50 percent chance, it was his clear duty to say so plainly in his directive to Kimmel... He won the battle for dominance of War Plans over Intelligence, and had to abide by the consequences. If his estimates had enabled the U.S. to fend off... the Japanese threat at Pearl Harbor, Turner would deserve the appreciation of a grateful nation. By the same token, he could not justly avoid his share of the blame for failure."

In December 1941, Turner was appointed Assistant Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (a new position created after Pearl Harbor for Admiral Ernest King), serving until June 1942. He was then sent to the Pacific to take command of the Amphibious Force, South Pacific Force. Over the next three years, he held a variety of senior Amphibious Force commands as a Rear Admiral and Vice Admiral. He helped plan and execute amphibious operations against enemy positions in the south, central and western Pacific. He would have commanded the amphibious component of the invasion of Japan. However, in August 1945 United States used atomic bombs on Japan, and Japan surrendered. Turner's invasion plans were never realized.

After World War II, Admiral Turner served on the Navy Department's General Board and was U.S. Naval Representative on the United Nations Military Staff Committee. He retired from active duty in July 1947. Admiral Turner died in Monterey, California, on February 12, 1961. He is buried in Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno, California, alongside his wife and Admirals Chester Nimitz, Raymond A. Spruance, and Charles A. Lockwood, an arrangement made by all of them while living.

The guided missile frigate (later cruiser) Richmond K. Turner was named in honor of Admiral Turner.

Turner was portrayed by actor Stuart Randall in the film The Gallant Hours.