<Back to Index>

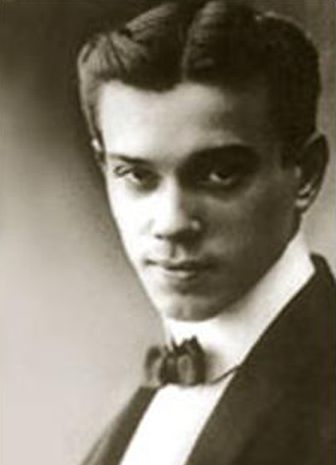

- Choreographer and Dancer Vatslav Fomic Nijinsky, 1890

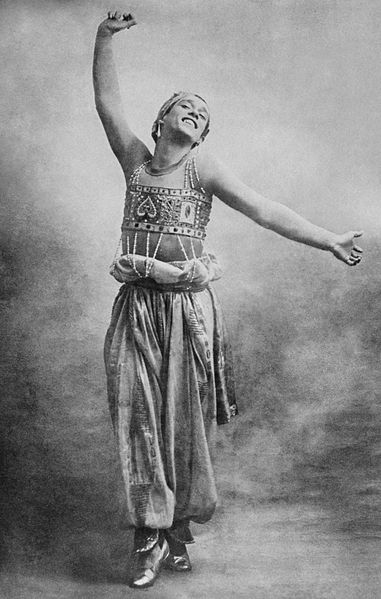

- Choreographer and Dancer Bronislava Fominichna Nijinska, 1891

PAGE SPONSOR

Vaslav (or Vatslav) Nijinsky (Russian: Ва́цлав Фоми́ч Нижи́нский / Vaclav Fomič Nižinskij; Polish: Wacław Niżyński; Ukrainian: Ва́цлав Томович Ніжи́нський; March 12, 1890 - April 8, 1950) was a Russian ballet dancer and choreographer of Polish descent, cited as the greatest male dancer of the 20th century. He grew to be celebrated for his virtuosity and for the depth and intensity of his characterizations. He could perform en pointe, a rare skill among male dancers at the time and his ability to perform seemingly gravity - defying leaps was also legendary. The choreographer Bronislava Nijinska was his sister. He also had a brother Stassik Nijinsky.

Vaslav Nijinsky was born in Kiev, Ukraine as Wacław Niżyński, to ethnic Polish parents, dancers Tomasz Niżyński and Eleonora Bereda. Nijinsky was christened in Warsaw, and considered himself to be a Pole despite difficulties in properly speaking the language as a result of his childhood in Russia's interior where his parents worked.

In 1900 Nijinsky joined the Imperial Ballet School, where he studied under Enrico Cecchetti, Nikolai Legat, and Pavel Gerdt. At 18 years old he was given a string of leads. In 1910, the company's Prima ballerina assoluta Mathilde Kschessinska selected Nijinsky to dance in a revival of Marius Petipa's Le Talisman, during which Nijinsky created a sensation in the role of the Wind God Vayou.

A turning point for Nijinsky was his meeting Sergei Diaghilev, a celebrated and highly innovative producer of ballet and opera as well as art exhibitions, who concentrated on promoting Russian visual and musical art abroad, particularly in Paris. Nijinsky and Diaghilev became lovers for a time, and Diaghilev was heavily involved in directing and managing Nijinsky's career. In 1909 Diaghilev took a company of Russian opera and ballet stars to Paris featuring Nijinsky and Anna Pavlova. The season of colorful Russian ballets and operas, works mostly new to the West, was a great success. It led Diaghilev to create his famous company the Ballets Russes with choreographer Michel Fokine and designer Léon Bakst. The Paris seasons of the Ballets Russes were an artistic and social sensation; setting trends in art, dance, music and fashion for the next decade.

Nijinsky's unique talent showed in Fokine's pieces such as Le Pavillon d'Armide (music by Nikolai Tcherepnin), Cleopatra (music by Anton Arensky and other Russian composers) and a divertissement La Fète. His expressive execution of a pas de deux from The Sleeping Beauty (Tchaikovsky) was a tremendous success; in 1910 he performed in Giselle, and Fokine's ballets Carnaval and Scheherazade (based on the orchestral suite by Rimsky - Korsakov). His partnership with Tamara Karsavina, also of the Mariinsky Theatre, was legendary, and they have been called the "most exemplary artists of the time".

Nijinsky took the creative reins and choreographed ballets, which pushed boundaries and stirred controversy. His ballets were L'après - midi d'un faune (The Afternoon of a Faun, based on Claude Debussy's Prélude à l'après - midi d'un faune) (1912), Jeux (1913), Till Eulenspiegel (1916). In The Rite of Spring (Le Sacre du Printemps), with music by Stravinsky (1913), Nijinsky created choreography that exceeded the limits of traditional ballet and propriety. For the first time, his audiences were experiencing the futuristic, new direction of modern dance. The radically angular movements expressed the heart of Stravinsky's radically modern score. Unfortunately, Nijinsky's new trends in dance caused a riotous reaction at the Théâtre de Champs - Élysées when they premiered in Paris. As the title character in L'après - midi d'un faune the final tableau (or scene), during which he mimed masturbation with the scarf of a nymph, caused a scandal; he was defended by such artists as Auguste Rodin, Odilon Redon and Marcel Proust.

In 1913 the Ballets Russes toured South America. Diaghilev did not make this journey, because of a superstitious fear that he would die on the ocean if he ever sailed. Free from supervision, Nijinsky became acquainted with Romola de Pulszky, a Hungarian countess. An ardent fan of Nijinsky, she took up ballet and used her family connections to get close to him. Despite her efforts to attract him, Nijinsky initially appeared unaware of her interest. When the company returned to Europe Diaghilev is reported to have flown into a rage, culminating in Nijinsky's dismissal.

During World War I, Nijinsky was interned in Hungary. Diaghilev with the help of King Alfonso XIII of Spain succeeded in getting him out for a North American tour in 1916. However, it was around this time in his life that signs of his schizophrenia were becoming apparent to members of the company. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia and taken to Switzerland by his wife, where he was treated unsuccessfully by psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler.

He

spent the rest of his life in and out of psychiatric hospitals and

asylums. During the last days of World War II, Nijinsky danced in public

for the last time. He encountered a group of Russian soldiers decamped

outside of Vienna, playing traditional folk tunes. Inspired by the music

and his reunion with his countrymen, he leapt into an exquisite dance,

astounding the men with the complexity and grace of his figures. The

experience restored some of Nijinsky's capacity for communication, after

having maintained long periods of almost absolute silence. Nijinsky died in a clinic in London on April 8, 1950 and was buried in London until 1953 when his body was moved to Montmartre Cemetery, Paris, France beside the graves of Gaétan Vestris, Théophile Gautier, and Emma Livry.

Nijinsky's daughter Kyra married the Ukrainian conductor Igor Markevitch, and they had a son named Vaslav. The marriage ended in divorce.

Nijinsky's Diary was written during the six weeks he spent in Switzerland before being committed to the asylum, combining elements of autobiography with appeals for compassion toward the less fortunate, and for vegetarianism and animal rights. Nijinsky writes of the importance of feeling as opposed to reliance on reason and logic alone, and he denounces the practice of art criticism as being nothing more than a way for those who practice it to indulge their own egos rather than focusing on what the artist was trying to say. The diary also contains bitter and conflicted thoughts regarding his relationship with Diaghilev.

As a dancer Nijinsky was extraordinary for his time. His main talent was probably as much in his charisma and skill in mime and characterization as strictly technical ability (Stanislas Idzikowski could leap as high and as far).

Nijinsky is immortalized in numerous still photographs, many of which were made by E.O. Hoppé,

who extensively photographed the Ballets Russes London seasons between

1909 and 1921. However no film exists of Nijinsky dancing. Diaghilev

never allowed the Ballets Russes to be filmed. He felt that the quality

of film at the time could never capture the artistry of his dancers and

that the reputation of the company would suffer if people saw it only in

short jerky films.

Bronislava Nijinska (Polish: Bronisława Niżyńska; Russian: Бронислава Фоминична Нижинская, Bronislava Fominichna Nizhinskaya; January 8, 1891 — old style 27 December 1890 - February 22, 1972) was a Russian dancer, choreographer, and teacher of Polish descent.

Nijinska was born in Minsk, the third child of the Polish dancers Tomasz and Eleonora Nijinska (née Bereda). Her brother was Vaslav Nijinsky. She was four years old when she made her theatrical debut in a Christmas pageant with her brothers in Nizhny Novgorod.

Nijinska played a leading role in the pioneering venture that turned against 19th century Classicism. A breakthrough came in 1910, when she created her first solo, the role Papillon in Le Carnival.

Nijinska was a member of the Imperial Ballet and then the Ballets Russes, for whom she choreographed her best known works, Les Noces (1923), The Blue Train (1924) and Les Biches (1924). She also choreographed the dances (to Felix Mendelssohn's music) for Max Reinhardt's 1935 film version of William Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream. Bronislava Nijinska died in Pacific Palisades, California.

She was twice married. Her first husband was Alexandre Kochetovsky, a fellow Ballet Russes dancer by whom she had two children - a son, Leo Kochetovsky, who was killed in a car accident and a daughter, Irina Nijinska, a ballet dancer in her own right who subsequently carried on her work, including editing and publishing her mother's memoirs in 1972. The true love of her life, but to whom she was never married, was the Russian bass singer Feodor Chaliapin.

She was the subject of an album The Nijinska Chamber by Kate Westbrook and Mike Westbrook.

Her students included the prima ballerina Maria Tallchief and the dancer Cyd Charisse.

Nijinska was inducted into the National Museum of Dance C.V. Whitney Hall of Fame in 1994.