<Back to Index>

- Prime Minister of Spain Francisco Largo Caballero, 1869

- Prime Minister of Spain Juan Negrín y López, 1892

PAGE SPONSOR

Francisco Largo Caballero (15 October 1869 – 23 March 1946) was a Spanish politician and trade unionist. He was one of the historic leaders of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) and of the Workers' General Union (UGT). During 1936 and 1937, Largo Caballero served as the Prime Minister of the Second Spanish Republic.

Born in Madrid, as a young man he made his living stuccoing walls. He participated in a construction workers strike in 1890 and joined the PSOE in 1894. Upon the death in 1925 of party founder Pablo Iglesias, he succeeded him as head of the party and of the UGT.

Moderate in his positions at the beginning of his political life, he advocated maintaining a degree of UGT cooperation with the dictatorial government of General Miguel Primo de Rivera, which permitted the union to continue functioning under his military dictatorship (that lasted from 1923 to 1930). This was the start of his political conflict with Indalecio Prieto, who opposed all collaboration with the dictatorial regime.

He was Minister of Labor Relations between 1931 and 1933, in the first governments of the Second Spanish Republic, headed by Niceto Alcalá - Zamora, and in that of his successor Manuel Azaña. He enjoyed great popularity among the masses of workers, who saw their own austere existences reflected in his way of life.

In the elections of 19 November 1933, the right wing Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right (CEDA) won power in Spain. The government nominally led by the centrist Radical Alejandro Lerroux was dependent on CEDA's parliamentary support. Responding to this reversal of fortune, Largo abandoned his moderate positions, began to talk of "socialist revolution", and became the leader of the left (Marxist and revolutionary) wing of the UGT and the PSOE. In early October 1934, after three CEDA ministers entered the government, he was one of the leaders of the failed armed rising of workers (mainly in Asturias) which was forcefully put down by the CEDA - dominated government.

He defended the pact of alliance with the other workers' political parties and trade unions, such as the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) and the anarchist trade union, the Confederacion Nacional del Trabajo (CNT). Once again, this placed him at odds with Prieto. He declared, that he, Largo Caballero "shall be the second Lenin", whose aim is the union of Iberian Soviet republics.

After the Popular Front won the elections in February 1936, president Manuel Azaña proposed that Prieto join the government, but Largo blocked these attempts at collaboration between PSOE and the Republican government. Largo dismissed fears of a military coup, and predicted that, were it to happen, a general strike would defeat it, opening the door to the workers' revolution.

In the event, the coup attempt by the colonial army and the right came on 17 July 1936. While not immediately successful, further actions by rebellious army units sparked the Spanish Civil War (1936 – 1939), in which the republic was ultimately defeated and destroyed.

On 4 September 1936, a few months into the civil war, he was designated the 134th Prime Minister and Minister of War. Besides conducting the war, he also focused on maintaining military discipline and government authority within the Republic. Nonetheless, the Barcelona May Days led to a governmental crisis that forced Caballero to resign on May 17th, 1937. Juan Negrín, also a member of the PSOE, was appointed Prime Minister in his stead.

Upon the defeat of the Republic in 1939, he fled to France. Arrested during the German occupation of France, he spent most of World War II imprisoned in the Sachsenhausen - Oranienburg concentration camp, until the liberation of the camps at the end of the war.

He died in exile in Paris in 1946; his remains were returned to Madrid in 1978.

His son, Francisco Largo Calvo, was imprisoned by the Francoists at the start of the Spanish Civil War and spent the entire war behind bars under the threat of execution. Largo Calvo fled Spain to Mexico in 1949 where he resided until his death in 2001.

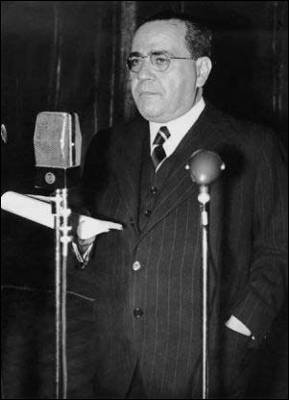

Juan Negrín y López (3 February 1892 – 12 November 1956) was a Spanish politician and physician.

Born in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Negrín came from a religious middle class family. He was a pupil of the Nobel Prize of Medicine winner, Ramon y Cajal, qualified as a doctor in Germany and later he became a university professor of physiology at the Complutense University of Madrid (Universidad Complutense de Madrid) at the age of 29. Negrin spoke English, French, German and also a little Russian.

On 21 July 1914 he married María Fidelman y Brodsky and had Juan Negrín y Fidelman, married to Rosita Díaz y Gimeno, Rómulo Negrín y Fidelman (Madrid, 1917 - 30 July 2004), married to Jeanne Fetter and father of Juan Román Negrín y Fetter (b. Mexico City, 20 September 1945), and Miguel Negrín y Fidelman.

Negrín joined the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) in 1929. He belonged to the Indalecio Prieto faction, opposed to that led by Largo Caballero, left wing extremists. In 1931 he was elected deputy for Las Palmas, in the Canary Islands. Negrin helped many people to escape from the revolutionary checas in July and August 1936.

He was named Minister of Finance in September 1936 in the government of Francisco Largo Caballero. As the finance minister, he built up the carabineros (custom guards), a force of 20,000 men which was later nicknamed The Hundred Thousand Sons of Negrín, in order to recover the control of the French frontier posts, which had been seized by the CNT. He

also took the controversial decision to transfer the Spanish gold

reserves to the Soviet Union in return for arms to continue the war

(October 1936). Worth $500 million at the time (another $240 million had been sent to France in July), critics argued that this action put the Republican government under the control of Joseph Stalin.

On 17 May 1937, Manuel Azaña (after Largo was dismissed) named Negrín the 135th President of the Government. Negrin's government included Indalecio Prieto named minister of War, Navy and Air, Julian Zugazagoitia as minister of interior (both socialists), the communists Jesus Hernandez as minister of education and Vicente Uribe as minister of agriculture, the republicans Jose Giral as foreign minister and Giner de los Rios as public work minister, the Basque Manuel Irujo as minister of justice and the Catalan Nationalist Ayguade as minister of labor. His main objectives were to fortify the central government, to reorganize and fortify the Republican army and to impose the law and order in the republican held area, against largely independent armed militias of the labor unions (CNT) and parties, thus curtailing the revolution inside the Republic. He also wanted to break the international isolation of the Republic in order to get the arms embargo lifted, and from 1938 to search an international mediation in order to finish the war. He also wished to normalize the position of the Catholic Church inside the Republic. All this was intended to connect the Spanish conflict with World War II, which he believed to be imminent, although the Munich Agreement definitively made all hope of outside aid vanish.

On the military level, along 1937 he launched a series of offensives on June (Huesca and Segovia), July, Brunete and August, Belchite, in order to halt the Nationalist offensive in the North, but all failed and by October the Nationalist had occupied all the North. On December, he launched an offensive in order to conquer Teruel, but by February the Republican Army retreated after suffering heavy losses and the Nationalists launched an offensive in Aragon, cutting in a half the Republican held zone. On July 1938 he launched an offensive in order to cross the Ebro River and reconnect the two Republican held zones. The Republican army managed to cross the Ebro, but by November had to retire after suffering heavy casualties and losing most of its material. Finally, on February 1939, he ordered an offensive in Extremadura in order to halt the Nationalist offensive against Catalonia, but was halted after a few days and Catalonia fell.

Although Negrín had always been a centrist in the PSOE, he maintained links with the Spanish Communist Party (PCE), whose policies at that point were in favor of a Popular Front alignment. One of the most controversial aspects of Negrín's government was its deep infiltration by the PCE, leading his critics - on both the Spanish left and right - to accuse him of being a puppet for the eventual establishment of a Stalinist communist state. The collapse of his government against the military golpe of Franco's forces destroyed any future development of the Spanish Republic. Negrín relied on the Communists to curtail the Anarchist wing of the Spanish Left, and was forced to rely on the Soviet Union, then led by Joseph Stalin, for weapons and armament, because of the arms embargo imposed by the Non - Intervention Committee. Soviet activities in Spain seemed to be focused as much or more on NKVD - directed purges of real or alleged Trotskyists and anarchists within the republican zone as on winning the war against the Phalange.

The military situation of the Spanish Republic deteriorated steadily under Negrín's government, largely because of the superior quality of the opposing generals and officers many of whom were veterans of the Rif War, and by 1938 the overwhelming advantage of the Nationalists in terms of men (20%), aircraft and artillery provided by Germany and Italy. On May 1938, Negrin issued the "Thirteen Points" (Trece Puntos), a program for peace negotiations, including absolute independence of Spain, liberty of conscience, protection of the regional liberties, universal suffrage, an amnesty for all Spaniards and agrarian reform, but Franco rejected any peace deal. Before the fall of Catalonia he proposed, in the meeting of the Cortes in Figueres, capitulation with the sole condition of respecting the lives of the vanquished and the holding of a plebiscite so the Spanish people could decide the form of government, but Franco rejected the new peace deal. On 9 February 1939, he moved to the Central Zone (30% of the Spanish territory) with the intention of defending the remaining territory of the republic until the start of the general European conflict, and organize the evacuation of those most at risk. Negrin thought that there were no other course but resistance, because the Nationalists rejected to negotiate any peace deal.

To fight on because there was no other choice, even if winning was not possible, then to salvage what we could - and at the very end our self respect... Why go on resisting? Quite simply because we knew what capitulation would mean.

However, Colonel Segismundo Casado, joined by José Miaja, Julian Besteiro and Cipriano Mera, tired of fighting, which they regarded then as hopeless. Seeking better surrender terms, they seized power in Madrid on 5 March 1939, created a military Junta, the Consejo Nacional de Defensa, and deposed Negrín. The same day, Negrin fled to France. Although the troops led by the PCE rejected the coup on Madrid they were defeated by Cipriano Mera's troops. The Junta tried to negotiate a peace deal with the nationalists, but Franco only accepted an unconditional surrender of the Republic. Finally all the members of the Junta (except Besteiro) fled, and by 31 of March 1939 the Nationalists seized all Spanish territory.

Unlike Spanish President Manuel Azaña, Negrín remained in Spain until the final collapse of the Republican front and his fall from office in March 1939. He organized the S.E.R.E. (Servicio de Evacuación de Refugiados Españoles) to help republican exiles. He remained prime minister of the Spanish Republican government in Exile between 1939 an 1945 (although ignored by most of the exiled political forces) and died in Paris in 1956.