<Back to Index>

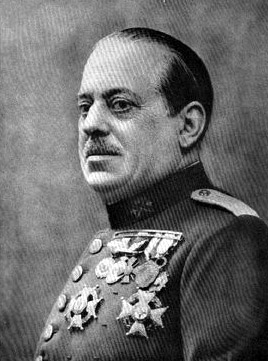

- General of the Spanish Army José Sanjurjo y Sacanell, 1872

- Commander of the Army of the North Emilio Mola y Vidal, 1887

PAGE SPONSOR

General José Sanjurjo y Sacanell, 1st Marquis of the Rif (March 28, 1872 – July 20, 1936) was a General in the Spanish Army who was one of the chief conspirators in the military uprising that led to the Spanish Civil War.

Sanjurjo was born in Pamplona. His father, Captain Justo Sanjurjo Bonrostra, was a Carlist. His mother was Carlota Sacanell Desojo.

He served in Cuba in 1896, in the Rif War (1909) in Morocco, and in the Rif War (1920), including the reconquest of lost territory in Melilla after the Battle of Annual in 1921. In 1922, he was assigned to investigate corruption in the army command of Larache. He was High Commissioner of Spain in Morocco and reached the rank of lieutenant general. In 1925 he participated in the amphibious landing at Alhucemas. With the completion of the 1920 Rif War, King Alfonso XIII awarded him the Gran Cruz de Carlos III on March 28, 1931. In 1928 he was made chief of a main directorate of the Civil Guard.

Miguel Primo de Rivera came to power in a military coup in 1923. He ran Spain as a military dictatorship. Gradually, his support faded, and de Rivera resigned in January 1930. General Dámaso Berenguer was ordered by the king to form a replacement government. This annoyed Sanjurjo, who considered himself far better qualified. Berenguer's dictablanda dictatorship failed to provide a viable alternative to de Rivera. In the municipal elections of 12 April 1931, little support was shown for pro - monarchy parties in the major cities, and large numbers of people gathered in the streets of Madrid. Asked if the government could count on the support of Sanjurjo's Civil Guard, he rejected the suggestion. King Alfonso XIII abdicated. The Second Spanish Republic was formed.

Thus, he became the first general appointed to army command by the Revolutionary Committee of the Republic. However, Sanjurjo was known to be a monarchist.

Sanjurjo clashed with Prime Minister Manuel Azaña over military policy and was replaced by General Miguel Cabanellas. He was demoted by Azaña to chief of the customs officers in 1932 because of the events of Castilblanco and Arnedo. This confrontation with the ministry, and Azaña's military reforms, and grants of regional autonomy to Catalonia and the Basque Country, led him to plot a rebellion with some Carlists of Fal Conde, the conde de Rodezno, and other military officers. This rebellion, which was known as the sanjurjada, was proclaimed in Seville on August 10, 1932. Sanjurjo asserted that the rebellion was only against the current ministry and not against the Republic. It achieved initial success in Seville but absolute failure in Madrid. Sanjurjo tried to flee to Portugal, but in Huelva he decided to give himself up.

He was condemned to death, a sentence which was later commuted to life imprisonment in the penitentiary of the Dueso. In March 1934 he was granted amnesty by the Lerroux government and went into exile in Estoril, Portugal.

When on May 10, 1936, Niceto Alcalá - Zamora was replaced as President of the Republic by Azaña, Sanjurjo joined with Generals Emilio Mola, Francisco Franco and Gonzalo Queipo de Llano in

a plot to overthrow the leftist Popular Front government. This led to

the Nationalist uprising on July 17, 1936, which started the Spanish

Civil War.

Sanjurjo died in Estoril in a plane crash on July 20, 1936, when he tried to fly back to Spain. He chose to fly in a small airplane piloted by Juan Antonio Ansaldo. One of the main reasons for the crash was the heavy luggage that Sanjurjo insisted on bringing. Ansaldo warned him that the load was too heavy, but Sanjurjo answered him:

- I need to wear proper clothes as the new caudillo of Spain.

Ironically, Sanjurjo chose to fly in Ansaldo's plane rather than a much larger and more suitable airplane that was available. It was an 8 passenger de Havilland Dragon Rapide, the same one which had transported Franco from the Canary Islands to Morocco. Sanjurjo apparently preferred the drama of flying with a "daring aviator". (Ansaldo survived the crash.)

When Mola also died in an aircraft accident, Franco was left as the effective leader of the Nationalist cause. This led to rumors that Franco had arranged the deaths of his two rivals, but no evidence has been produced to support this allegation.

The opening of the alternate history fiction writer Harry Turtledove's novel Hitler's War in his series The War That Came Early begins with Sanjurjo's flight from Portugal. The point of divergence is

that he accepts the pilot's advice and abandons the luggage, the flight

no longer being overloaded and thus arriving safely. His behavior from

that point on is described as if he diverged from the actual one of

Franco, with Spain taking a less isolated role in World War II.

Emilio Mola y Vidal, 1st Duke of Mola, Grandee of Spain (June 9, 1887 – June 3, 1937) was a Spanish Nationalist commander during the Spanish Civil War. He is best known for having coined the term "fifth column".

Mola was born in Placetas, Cuba - at that time a Spanish province - where his father, an army officer, was stationed. He enrolled in the Infantry Academy of Toledo in 1907. He served in Spain's colonial war in Morocco where he received the Medalla Militar Individual, and became an authority on military affairs. By 1927 he was a Brigadier general.

Mola

was made Director General of Security in 1930. This was a political

post and his conservative views made him unpopular with opposition liberal and socialist politicians. When the left wing Popular Front government was elected in February 1936 Mola was made military governor of Pamplona in Navarre, which the government regarded as a backwater. But the area was a center of Carlist activity and Mola himself secretly collaborated with the movement.

In the spring of 1936, Mola joined a group of army officers led by José Sanjurjo who desired to oust the Popular Front government. Mola's energy and organizational ability soon made him the group's chief planner, while Sanjurjo remained a figurehead. Mola, whose codename was director, sent secret instructions to the various military units to be involved in the uprising. After several delays, July 18, 1936 was chosen as the date of the coup. Francisco Franco's participation was not confirmed until early July. Although events ran ahead of schedule in the Spanish Protectorate of Morocco, Mola waited until July 19 to proclaim the revolt. When Mola's brother was captured by the Republicans in Barcelona, the government threatened his life. Mola replied: "No, he knows how to die as an officer. I can neither take back my word to my followers and probably you cannot either from yours." Mola then ordered systematic executions in captured cities for the purpose of instilling fear.

The Nationalist coup failed to gain control of either Madrid or other urban areas, though most of the army supported it. As the situation devolved into civil war, Sanjurjo was killed in an air crash on July 20. Mola then became Nationalist commander in the north, while Franco became commander in the south. On September 5, a Nationalist offensive sent by General Mola under Colonel Alfonso Beorlegui took Irún and closed the French border. Mola's forces went on to secure the whole of the province of Guipúzcoa, isolating the remaining Republican provinces in the north.

A junta in Burgos proved unable to set overall strategy thus Franco was chosen commander - in - chief at a meeting of ranking generals on September 21. Mola continued to command the Army of the North and led an unsuccessful effort to take Madrid in October. In a radio address, he described Nationalists sympathizers in the city as a "fifth column" that supplemented his four military columns.

Mola died on June 3, 1937, when the aircraft in which he was traveling crashed in bad weather while returning to Vitoria. The deaths of Sanjurjo and Mola left Franco as the preeminent leader of the Nationalist cause. This led to the suspicion that Franco contributed in some way to the deaths of his two rivals, but no evidence has been produced. Generalissimo Franco as Head of the Spanish State granted him the posthumous title of Duke of Mola, Grandee of Spain, and the title was immediately succeeded by his son, Emilio Mola y Bascón.