<Back to Index>

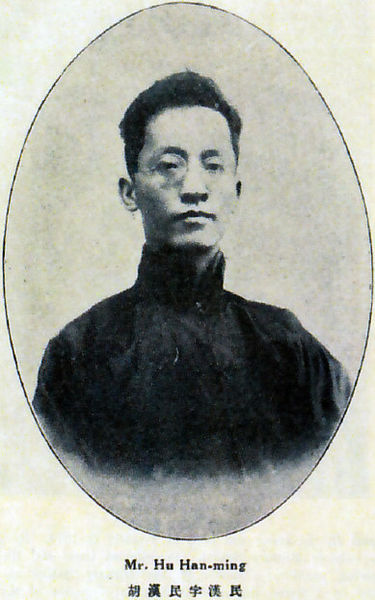

- Leader of Kuomintang Hu Hanmin, 1879

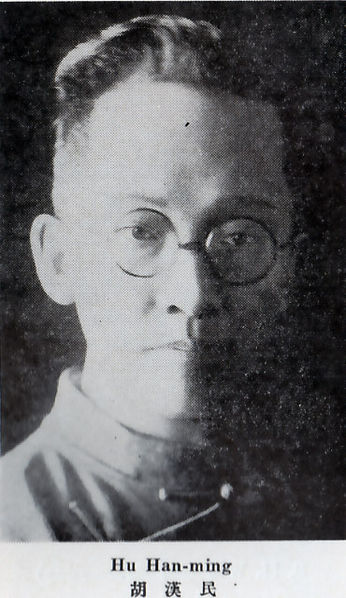

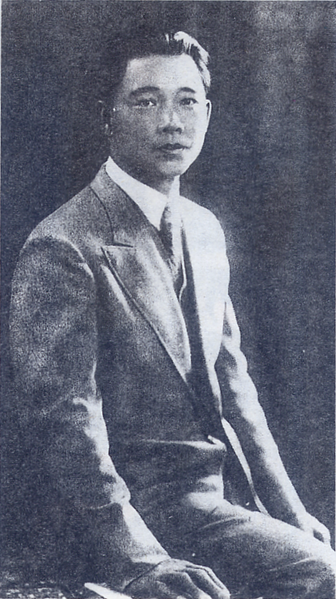

- President of the Republic of China Wang Jingwei, 1883

PAGE SPONSOR

Hu Hanmin (traditional Chinese: 胡漢民; simplified Chinese: 胡汉民; born in Panyu, Guangdong, China, December 9, 1879; died in Guangdong, China, May 12, 1936) was one of the early leaders of Kuomintang (KMT), and a very important right - winger in Kuomintang.

Hu Hanmin was qualified as juren at 21 years of age. He studied in Japan since 1902, and joined Tongmenghui as an editor of ``Minbao" in 1905. From 1907 - 1910, he participated in several armed revolutions. Shortly after the Xinhai Revolution in 1911, he was appointed the governor of Guangdong and chief secretary of the Provisional Government. He participated in the Second Revolution in 1913, and followed Sun Yat-sen to Japan after the failure of that revolution. There they established the Chinese Revolutionary Party. Hu lived in Guangdong between 1917 and 1921 and worked for Sun Yat-sen, as the minister of transportation first and principal consultant later.

Hu was elected to be a central executive committee member in the first conference of Kuomintang in January, 1924. In September, he acted as vice generalissimo, when Sun Yat-sen left Guangzhou to Shaoguan. Sun died in Beijing in March, 1925, and Hu was one of the three most powerful figures in Kuomintang. The other two were Wang Jingwei and Liao Zhongkai. Liao was assassinated in August of the same year, and Hu was suspected and arrested. After the Ninghan split in 1927, Hu supported Chiang Kai-Shek and was head of Legislative Yuan in Nanjing.

Later on February 28, 1931, he was placed under house arrest by Chiang because of disputes over the new provisional constitution. Internal party pressure forced Chiang to release him. After that, he became a powerful leader in South China, holding three political principles of resistance: resistance against Japanese invasion and massacre, resistance against militarist Communists, and finally resistance against the self - proclaimed leader, Chiang Kai-shek. The anti - Chiang factions in the KMT converged on Guangzhou to set up a rival government. They demanded Chiang's resignation from his dual posts of president and premier. Civil war was averted by the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. Hu continued to rule southern China, the heartland of the KMT, with the help of Chen Jitang and the New Guangxi clique. There he attempted to create a model government free of corruption and cronyism to discredit Chiang's Nanjing regime.

Hu was an advocate of action against Japanese aggression, criticizing Chiang for "his spineless failure to adopt a strong policy toward the foreign power which has torn and ravaged our homeland!"

Hu visited Europe and stopped his political attack on Chiang Kai-shek in June, 1935. In the first session of the fifth conference of Kuomintang in December 1935, he was absently elected as the Chair of Central Committee of Common Affairs. Hu returned to China in January, 1936, and lived in Guangzhou until he died of cerebral hemorrhage on May 12, 1936.

His death sparked a crisis. Chiang wanted to replace Hu with loyal followers in southern China and end the autonomy the south enjoyed under Hu. As a result Chen and the New Guangxi clique conspired to remove Chiang from office. In the so - called "Liangguang Incident", Chen was forced to resign as governor of Guangdong after Chiang bribed many of Chen's officers to defect and the conspiracy collapsed.

Hu's political philosophy was that one's individual rights are a function of one's membership in a nation.

Wang Jingwei (4 May 1883 – 10 November 1944), alternate name Wang Zhaoming, was a Chinese politician. He was initially known as a member of the left wing of the Kuomintang (KMT), but later became increasingly anti - Communist after his efforts to collaborate with the CCP ended in political failure. His politics veered sharply to the right later in his career, after he joined the Japanese.

A close associate of Sun Yat-sen, Wang is most noted for disagreements with Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and for his formation of a Japanese supported collaborationist government in Nanjing. For this role he has often been labeled as a Hanjian. His name in mainland China is also now a term used to refer to a traitor, similar to "Benedict Arnold" for Americans or "Quisling" for Norwegians.

Born in Sanshui, Guangdong, but of Zhejiang origin, Wang went to Japan as an international student sponsored by the Qing government in 1903, and joined the Tongmenghui in

1905. As a young man, Wang came to blame the Qing dynasty for holding

China back, and making it too weak to fight off exploitation by Western Imperialist powers.

While in Japan, Wang became a close confidant of Sun Yat-Sen, and would

later go on to become one of the most important members of the early

Kuomintang.

In the years leading up to the 1911 Revolution, Wang was active in opposing the Qing. Wang gained prominence during this period as an excellent public speaker and a staunch advocate of Chinese nationalism. He was jailed for plotting an assassination of the regent, the 2nd Prince Chun, and readily admitted his guilt at trial. He remained in jail from 1910 until the Wuchang Uprising the next year, and became something of a national hero upon his release.

During and after the 1911 Revolution, Wang’s political life was defined by his opposition to Western Imperialism. In the early 1920s, he held several posts in Sun Yat-sen's Revolutionary Government in Guangzhou,

and was the only member of Sun's inner circle to accompany him on trips

outside of KMT - held territory in the months immediately preceding

Sun's

death. He is believed by many to have drafted Sun's will during the

short period before Sun's death, in the winter of 1925. He was

considered one of the main contenders to replace Sun as leader of the Kuomintang, but eventually lost control of the party and army to Chiang Kai-shek. Wang had clearly lost control of the KMT by 1926, when, following the Zhongshan Warship Incident,

Chiang successfully sent Wang and his family to vacation in Europe. It

was important for Chiang to have Wang away from Guangdong while Chiang

was in the process of expelling communists from the KMT because Wang was

then the leader of the left wing of the KMT, notably sympathetic to

communists and communism, and may have opposed Chiang if he had remained in China.

During the Northern Expedition, Wang was the leading figure in the left leaning faction of the KMT that called for continued cooperation with the Chinese Communist Party. Although Wang collaborated closely with Chinese Communists in Wuhan, he was philosophically opposed to communism and regarded the KMT’s Comintern advisors with suspicion. He did not believe that Communists could be true patriots or true Chinese nationalists.

In early 1927, shortly before Chiang Captured Shanghai and moved the capital to Nanjing, Wang's faction declared the capital of the Republic to be Wuhan. While attempting to direct the government from Wuhan, Wang was notable for his close collaboration with leading Communist figures, including Mao Zedong, Chen Duxiu, and Borodin, and for his faction's provocative land reform policies. Wang later blamed the failure of his Wuhan government on its excessive adoption of Communist agendas. Wang's regime was opposed by Chiang Kai-shek, who was in the midst of a bloody purge of Communists in Shanghai and was calling for a push farther north. The separation between the governments of Wang and Chiang are known as the "Ninghan Separation" (simplified Chinese: 宁汉分裂; traditional Chinese: 寧漢分裂).

Chiang Kai-shek occupied Shanghai in April 1927, and began a bloody suppression of suspected Communists known as the "White Terror".

Within several weeks of Chiang's suppression of Communists in Shanghai

Wang's leftist government was attacked by a KMT aligned warlord and

disintegrated, leaving Chiang as the sole legitimate leader of the

Republic. KMT troops occupying territories formerly controlled by Wang

conducted massacres of suspected Communists in those areas: around Changsha alone,

over ten thousand people were killed in a single twenty day period.

Fearing retribution as a Communist sympathizer, Wang publicly claimed

allegiance to Chiang and fled to Europe.

Between 1929 and 1930, Wang collaborated with Feng Yuxiang and Yan Xishan to form a central government in opposition to the one headed by Chiang. Wang took part in a conference hosted by Yan to draft a new constitution, and was to serve as the Prime Minister under Yan, who would be President. Wang's attempts to aid Yan's government ended when Chiang defeated the alliance in the Central Plains War.

In 1931, Wang joined another anti - Chiang government in Guangzhou. After Chiang defeated this regime, Wang reconciled with Chiang's Nanjing government and held prominent posts for most of the decade. Wang was appointed premier just as the Battle of Shanghai (1932) began. He had frequent disputes with Chiang and would resign in protest several times only to have his resignation rescinded. As a result of these power struggles within the KMT, Wang was forced to spend much of his time in exile. He traveled to Germany, and maintained some contact with Adolf Hitler. The effectiveness of the KMT was constantly hindered by leadership and personal struggles, such as that between Wang and Chiang. In December 1935, Wang permanently left the premiership after being seriously wounded during an assassination attempt a month earlier.

During the 1936 Xian Incident, in which Chiang was taken prisoner by his own general, Zhang Xueliang, Wang favored sending a "punitive expedition" to attack Zhang. He was apparently ready to march on Zhang, but Chiang's wife, Soong Meiling, and brother, T.V. Soong, feared that such an action would lead to Chiang's death and his replacement by Wang, so they successfully opposed this action.

Wang Jingwei accompanied the government on its retreat to Chongqing during the Second Sino - Japanese War (1937 – 1945).

During this time, he organized some right - wing groups under European

fascist lines inside the KMT. Wang was originally part of the pro-war

group; but, after the Japanese were successful in occupying large areas

of coastal China, Wang became known for his pessimistic view on China's

chances in the war against Japan. He

often voiced defeatist opinions in KMT staff meetings, and continued to

express his view that Western Imperialism was the greater danger to

China, much to the chagrin of his associates. Wang believed that China

needed to reach a negotiated settlement with Japan so that Asia could

resist Western Powers.

In late 1938, Wang left Chongqing for Hanoi, French Indochina, where he stayed for three months and announced his support for a negotiated settlement with the Japanese. During this time, he was wounded in an assassination attempt by KMT agents. Wang then flew to Shanghai, where he entered negotiations with Japanese authorities. The Japanese invasion had given him the opportunity he had long sought to establish a new government outside of Chiang Kai-shek’s control.

On 30 March 1940, Wang became the head of state of what came to be known as the Wang Jingwei regime based in Nanjing, serving as the President of the Executive Yuan and Chairman of the National Government (行政院長兼國民政府主席). In November, 1940, Wang's government signed the "Sino - Japanese Treaty" with the Japanese, a document that has been compared with Japan's Twenty-one Demands for its broad political, military, and economic concessions. In June, 1941, Wang gave a public radio address from Tokyo in which he praised Japan, affirmed China's submission to it, criticized the Kuomintang government, and pledged to work with the Empire of Japan to resist Communism and Western imperialism. Wang continued to orchestrate politics within his regime in concert with Chiang's international relationship with foreign powers, seizing the French Concession and the International Settlement of Shanghai in 1943, after Western nations agreed by consensus to abolish extraterritoriality.

The Government of National Salvation of the collaborationist "Republic of China", which Wang headed, was established on the Three Principles of Pan - Asianism, anti - Communism, and opposition to Chiang Kai-shek. Wang continued to maintain his contacts with German Nazis and

Italian fascists he had established while in exile. In March 1944, Wang

left for Japan to undergo medical treatment for the wound left by an

assassination attempt in 1939. He died in Nagoya on

10 November 1944, less than a year before Japan's surrender to the

Allies, thus avoiding a trial for treason. Many of his senior followers

who lived to see the end of the war were executed. Wang was buried in

Nanjing near the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum,

in an elaborately constructed tomb. Soon after Japan's defeat, the

Kuomintang government under Chiang Kai-shek moved its capital back to

Nanjing, destroyed Wang's tomb, and burned the body. Today the site is

commemorated with a small pavilion that notes Wang as a traitor.

Chinese under the regime had greater access to coveted war time luxuries, and the Japanese enjoyed things like matches, rice, tea, coffee, cigars, foods, and alcoholic drinks, all of which were scarce in Japan proper, but consumer goods became more scarce after Japan entered World War II. In Japanese occupied Chinese territories the prices of basic necessities rose substantially as Japan's war effort expanded. In Shanghai of 1941, they increased eleven - fold.

Daily life was often difficult in the Nanjing Nationalist Government controlled Republic of China, and grew increasingly so as the war turned against Japan (c.1943). Local residents resorted to the black market in order to obtain needed items or to influence the ruling establishment. The Japanese Kempeitai, Japanese Tokko, collaborationist Chinese police, and Chinese citizens in the service of the Japanese all worked to censor information, monitor any opposition, and torture enemies and dissenters. A "native" secret agency, the Tewu, was created with the aid of Japanese Army "advisors". The Japanese also established prisoner - of - war detention centers, concentration camps, and Kamikaze training centers to indoctrinate pilots.

Since Wang’s government held authority only over territories under Japanese military occupation, there was a limited amount that officials loyal to Wang could do to ease the suffering of Chinese under Japanese occupation. Wang himself became a focal point of anti - Japanese resistance. He was demonized and branded as an “arch - traitor” in both KMT and Communist rhetoric. Wang and his government were deeply unpopular with the Chinese populace, who regarded them as traitors to both the Chinese state and Han Chinese identity. Wang’s rule was constantly undermined by resistance and sabotage.

The strategy of the local education system was to create a workforce suited for employment in factories and mines, and for manual labor. The Japanese also attempted to introduce their culture and dress to the Chinese. Complaints and agitation called for more meaningful Chinese educational development. Shinto temples and similar cultural centers were built in order to instill Japanese culture and values. These activities came to a halt at the end of the war.

For his role in the Pacific War, Wang has been considered a traitor by most post - World War II Chinese historians in both Taiwan and Mainland China. His name has become a byword for "traitor" or "treason" in Mainland China and Taiwan. The Mainland’s Communist government despised Wang not only for his collaboration with the Japanese, but also for his anti - Communism, while the KMT downplayed his anti - Communism and emphasized his collaboration and betrayal of Chiang Kai-Shek. The Communists also used his KMT ties to demonstrate what they saw as the duplicitous, treasonous nature of the Kuomintang. Both sides downplayed his earlier association with Sun Yat-Sen because of his eventual collaboration.

Wang was married to Chen Bijun and had six children with her, five of which survived into adulthood. Of those who survived into adulthood, Wang's eldest son, Wen - Jin, was born in France in 1913. Wang's eldest daughter, Wen - Xing, was born in France in 1915, and is now living in New York. Wang's second daughter, Wang Wenbin, was born in 1920. Wang's third daughter, Wen - Xun, was born in Guangzhou in 1922, and died in 2002 in Hong Kong. Wang's second son, Wen - ti, was born in 1928, and was sentenced for being a hanjian in 1946.