<Back to Index>

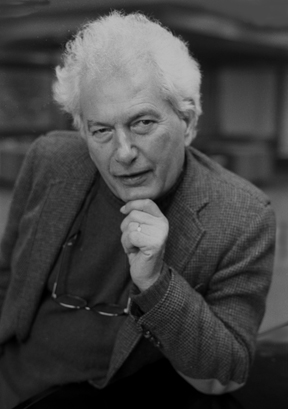

- Novelist and Playwright Joseph Heller, 1923

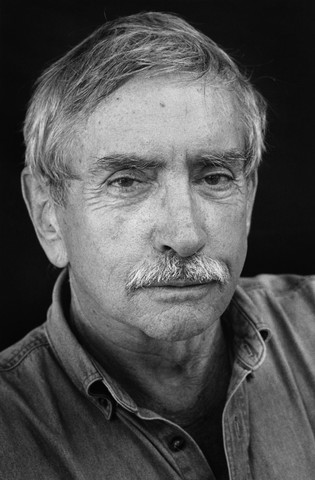

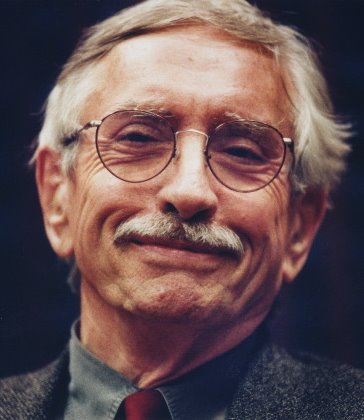

- Playwright Edward Franklin Albee III, 1928

PAGE SPONSOR

Joseph Heller (May 1, 1923 – December 12, 1999) was a US satirical novelist, short story writer, and playwright. His best known work is Catch-22, a novel about US servicemen during World War II. The title of this work entered the English lexicon to refer to absurd, no-win choices, particularly in situations in which the desired outcome of the choice is an impossibility, and regardless of choice, the same negative outcome is a certainty. Heller is widely regarded as one of the best post World War II satirists. Although he is remembered primarily for Catch-22, his other works center on the lives of various members of the middle class and remain exemplars of modern satire.

Joseph Heller was born in Coney Island in Brooklyn, New York, the son of poor Jewish parents, Lena and Isaac Donald Heller, from Russia. Even as a child, he loved to write; as a teenager, he wrote a story about the Russian invasion of Finland and sent it to New York Daily News, which rejected it. At least one scholar suggests that he knew that he wanted to become a writer, after recalling that he received a children's version of the Iliad when he was ten. After graduating from Abraham Lincoln High School in 1941, Heller spent the next year working as a blacksmith's apprentice, a messenger boy, and a filing clerk. In 1942, at age 19, he joined the U.S. Army Air Corps. Two years later he was sent to the Italian Front, where he flew 60 combat missions as a B-25 bombardier. His Unit was the 488th Bombardment Squadron, 340th Bomb Group, 12th Air Force. Heller later remembered the war as "fun in the beginning... You got the feeling that there was something glorious about it." On his return home he "felt like a hero... People think it quite remarkable that I was in combat in an airplane and I flew sixty missions even though I tell them that the missions were largely milk runs." ("Milk Runs" were combat missions, but mostly uneventful due to a lack of intense opposition from enemy anti - aircraft artillery or fighters.)

After the war, Heller studied English at the University of Southern California and NYU on the G.I. Bill. In 1949, he received his M.A. in English from Columbia University. Following his graduation, he spent a year as a Fulbright scholar at St. Catherine's College in Oxford University. After returning home, he taught composition at The Pennsylvania State University for two years. He also taught fiction and dramatic writing at Yale. He then briefly worked for Time, Inc., before taking a job as a copywriter at a small advertising agency, where he worked alongside future novelist Mary Higgins Clark. At home, Heller wrote. He was first published in 1948, when The Atlantic ran one of his short stories. That first story nearly won the "Atlantic First."

He was married to Shirley Held from 1945 – 1981 and they had two children, Erica (born 1952) and Ted (born 1956).

While sitting at home one morning in 1953, Heller thought of the lines, "It was love at first sight. The first time he saw the chaplain, Someone fell madly in love with him." Within the next day, he began to envision the story that could result from this beginning, and invented the characters and the plot, as well as the tone and form that the story would eventually take. Within a week, he had finished the first chapter and sent it to his agent. He did not do any more writing for the next year, as he planned the rest of the story. The initial chapter was published in 1955 as "Catch-18", in Issue 7 of New World Writing.

Although he originally did not intend the story to be longer than a novelette, Heller was able to add enough substance to the plot that he felt it could become his first novel. When he was one third done with the work, his agent, Candida Donadio, began submitting the novel to several publishers. Heller was not particularly attached to the work, and decided that he would not finish it if publishers were not interested. The work was never rejected, and was soon purchased by Simon and Schuster, who gave him US $750 and promised him an additional $750 when the full manuscript was delivered. Heller missed his deadline by four to five years, but, after eight years of thought, delivered the novel to his publisher.

The finished novel describes the wartime experiences of Army Air Corps Captain John Yossarian. Yossarian devises multiple strategies to avoid combat missions, but the military bureaucracy is always able to find a way to make him stay. As Heller observed, "Everyone in my book accuses everyone else of being crazy. Frankly, I think the whole society is nuts — and the question is: What does a sane man do in an insane society?" Heller has also commented that "peace on earth would mean the end of civilization as we know it" — perhaps further food for thought when reading Catch-22, in which the concept and circumstances of war are so overwhelming and fundamental.

Just before publication, the novel's title was changed to Catch-22 to avoid confusion with Leon Uris's new novel, Mila 18. The novel was published in hardback in 1961 to mixed reviews, with the Chicago Sun - Times calling it "the best American novel in years", while other critics derided it as "disorganized, unreadable, and crass". It sold only 30,000 copies in the United States hardback in its first year of publication. (Reaction was very different in Great Britain, where, within one week of its publication, the novel reached number one on the bestseller lists.) Once it was released in paperback in October 1962, however, Catch-22 caught the imaginations of many baby - boomers, who identified with the novel's anti - war sentiments. The book went on to sell 10 million copies in the United States. The novel's title became a buzzword for a dilemma with no easy way out. Now considered a classic, the book was listed at number 7 on Modern Library's list of the top 100 novels of the century. The United States Air Force Academy uses the novel to "help prospective officers recognize the dehumanizing aspects of bureaucracy."

The movie rights to the novel were purchased in 1962, and, combined with his royalties, made Heller a millionaire. The film, which was directed by Mike Nichols and starred Alan Arkin, Jon Voight and Orson Welles, was not released until 1970.

Shortly after Catch-22 was published, Heller thought of an idea for his next novel, which would become Something Happened, but did not act on it for two years. In the meantime he focused on scripts, completing the final screenplay for the movie adaptation of Helen Gurley Brown's Sex and the Single Girl, as well as a television comedy script that eventually aired as part of "McHale's Navy". He also completed a play in only six weeks, but spent a great deal of time working with the producers as it was brought to the stage.

In 1969, Heller wrote a play called We Bombed in New Haven. It delivered an anti - war message while discussing the Vietnam War. It was originally produced by the Repertory Company of the Yale Drama School, with Stacey Keach in the starring role. After a slight revision, it was published by Alfred Knopf and then debuted on Broadway, starring Jason Robards.

Heller's follow up novel, Something Happened,

was finally published in 1974. Critics were enthusiastic about the

book, and both its hardcover and paperback editions reached number one

on the New York Times bestseller list. Heller wrote another five novels, each of which took him several years to complete. One of them, Closing Time, revisited many of the characters from Catch-22 as they adjusted to post war New York. All of the novels sold respectably well, but could not duplicate the success of his debut. Told by an interviewer that he had never produced anything else as good as Catch-22, Heller famously responded, "Who has?"

Heller did not begin work on a story until he had envisioned both a first and last line. The first sentence usually appeared to him "independent of any conscious preparation". In most cases, the sentence did not inspire a second sentence. At times, he would be able to write several pages before giving up on that hook. Usually, within an hour or so of receiving his inspiration, Heller would have mapped out a basic plot and characters for the story. When he was ready to begin writing, he focused on one paragraph at a time, until he had three or four handwritten pages, which he then spent several hours reworking.

Heller maintained that he did not "have a philosophy of life, or a need to organize its progression. My books are not constructed to 'say anything.'" Only when he was almost one third finished with the novel would he gain a clear vision of what it should be about. At that point, with the idea solidified, he would rewrite all that he had finished and then continue to the end of the story. The finished version of the novel would often not begin or end with the sentences he had originally envisioned, although he usually tried to include the original opening sentence somewhere in the text.

In the 1970s Heller taught creative writing at the City College of New York. After the publication of Catch-22,

Heller resumed a part time academic career as a teacher of creative

writing at Yale University and at the University of Pennsylvania.

On Sunday, December 13, 1981, Heller was diagnosed with Guillain - Barré syndrome, a debilitating syndrome that was to leave him temporarily paralyzed. He was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit of Mount Sinai Medical Hospital the same day, and remained there, bedridden, until his condition had improved enough to permit his transfer to the Rusk Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine, which occurred on January 26, 1982. His illness and recovery are recounted at great length in the autobiographical No Laughing Matter, which contains alternating chapters by Heller and his good friend Speed Vogel. The book reveals the assistance and companionship Heller received during this period from a number of his prominent friends — Mel Brooks, Mario Puzo, Dustin Hoffman and George Mandel among them.

Heller

eventually made a substantial recovery. In 1984, while in the process

of divorcing his wife of 35 years, he met Valerie Humphries, the nurse

who had helped him to recover, and later married her.

Heller returned to St. Catherine's as a visiting Fellow, for a term, in 1991 and was appointed an Honorary Fellow of the college. In 1998, he released a memoir, Now and Then: From Coney Island to Here, in which he relived his childhood as the son of a deliveryman and offered some details about the inspirations for Catch-22.

He died of a heart attack at his home in East Hampton, on Long Island, in December 1999, shortly after the completion of his final novel, Portrait of an Artist, as an Old Man. On hearing of Heller's death, his friend Kurt Vonnegut said, "Oh, God, how terrible. This is a calamity for American literature."

In April 1998, Lewis Pollock wrote to The Sunday Times for

clarification as to "the amazing similarity of characters, personality

traits, eccentricities, physical descriptions, personnel injuries and

incidents" in Catch-22 and a novel published in England in 1951. The book that spawned the request was written by Louis Falstein and titled The Sky is a Lonely Place in Britain and Face of a Hero in the United States. Falstein's novel was available two years before Heller wrote the first chapter of Catch-22 (1953) while he was a student at Oxford. The Times stated: "Both have central characters who are using their wits to escape the

aerial carnage; both are haunted by an omnipresent injured airman,

invisible inside a white body cast". Stating he had never read

Falstein's novel, or heard of him, Heller

said: "My book came out in 1961[;] I find it funny that nobody else has

noticed any similarities, including Falstein himself, who died just

last year".

Edward Franklin Albee III (born March 12, 1928 - September 16, 2016) was an American playwright who is best known for The Zoo Story (1958), The Sandbox (1959), Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1962), and a rewrite of the book for the unsuccessful musical version of Truman Capote's Breakfast at Tiffany's (1966). His works are considered well crafted, often unsympathetic examinations of the modern condition. His early works reflect a mastery and Americanization of the Theatre of the Absurd that found its peak in works by European playwrights such as Jean Genet, Samuel Beckett, and Eugène Ionesco. Younger American playwrights, such as Paula Vogel, credit Albee's daring mix of theatricalism and biting dialogue with helping to reinvent the post war American theater in the early 1960s. Later in his life, Albee continued to experiment in works, such as The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia? (2002).

According to Magill's Survey of American Literature (2007), Edward Albee was born somewhere in Virginia (the popular belief is that he was born in Washington, D.C.). He was adopted two weeks later and taken to Larchmont, New York, in Westchester County, where he grew up. Albee's adoptive father, Reed A. Albee, the wealthy son of vaudeville magnate Edward Franklin Albee II, owned several theaters. Here the young Edward first gained familiarity with the theater as a child. His adoptive mother, Reed's third wife, Frances tried to raise Albee to fit into their social circles.

Albee attended the Clinton High School, then the Lawrenceville School in New Jersey, from which he was expelled. He then was sent to Valley Forge Military Academy in Wayne, Pennsylvania, where he was dismissed in less than a year. He enrolled at The Choate School (now Choate Rosemary Hall) in Wallingford, Connecticut, graduating in 1946. His formal education continued at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, where he was expelled in 1947 for skipping classes and refusing to attend compulsory chapel. In response to his expulsion, Albee's play Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? is believed to be based on his experiences at Trinity College.

Albee left home for good when he was in his late teens. In a later interview, he said: "I never felt comfortable with the adoptive parents. I don't think they knew how to be parents. I probably didn't know how to be a son, either." In a 2008 interview, he told interviewer Charlie Rose that he was "thrown out" because his parents wanted him to become a "corporate thug" and didn't approve of his aspirations to become a writer.

Albee moved into New York's Greenwich Village, where he supported himself with odd jobs while learning to write plays. His first play, The Zoo Story, was first staged in Berlin. The less than diligent student later

dedicated much of his time to promoting American university theater. He became a distinguished professor at the University of Houston, where he taught an exclusive playwriting course. His plays are published by Dramatists Play Service and Samuel French, Inc..

Albee was openly gay and stated that he first knew he was gay at age 12 and a half. He insisted, however, that he did not want to be known as a "gay writer," stating in his acceptance speech for the 2011 Lambda Literary Foundation's Pioneer Award for Lifetime Achievement: "A writer who happens to be gay or lesbian must be able to transcend self. I am not a gay writer. I am a writer who happens to be gay."

A former member of the Dramatists Guild Council, Albee received three Pulitzer Prizes for drama — for A Delicate Balance (1967), Seascape (1975), and Three Tall Women (1994). His play Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf was selected for the 1963 Pulitzer Prize by the award's drama jury, but was overruled by the advisory committee, which elected not to give a drama award at all. Albee was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1972. He received a Special Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement (2005); the Gold Medal in Drama from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters (1980); as well as the Kennedy Center Honors and the National Medal of Arts (both in 1996). In 2009 Albee received honorary degree a.k.a. "Doctor Honoris Causa" by the Bulgarian National Academy of Theater and Film Arts (NATFA) - a member of the Global Alliance of Theater Schools.

Albee was the President of the Edward F. Albee Foundation, Inc., which maintains the William Flanagan Memorial Creative Persons Center, a writers and artists colony in Montauk, New York, better known at ``The Barn".

In 2008, in celebration of Albee's eightieth birthday, a number of his plays were mounted in distinguished Off Broadway venues, including the historic Cherry Lane Theatre. The playwright directed two of his one acts, The American Dream and The Sandbox there. These were first produced at the theater in 1961 and 1962, respectively.

Despite being gay,

Albee was briefly engaged to Larchmont debutante Delphine Weissinger,

and although their relationship ended when she moved to England, he

remained a close friend of the Weissinger family. Growing up, he often

spent more of his time in the Weissinger household than he did in his

own, due to discord with his adoptive parents.

His longtime partner, Jonathan Thomas, a sculptor, died on May 2, 2005, from bladder cancer. They had been partners from 1971 until Thomas's death. Albee also had a relationship of several years with playwright Terrence McNally during the 1950s.

Albee died at his Montauk, New York, home on September 16, 2016, aged 88.