<Back to Index>

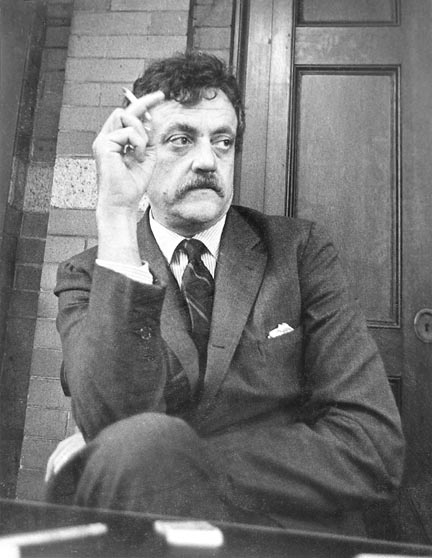

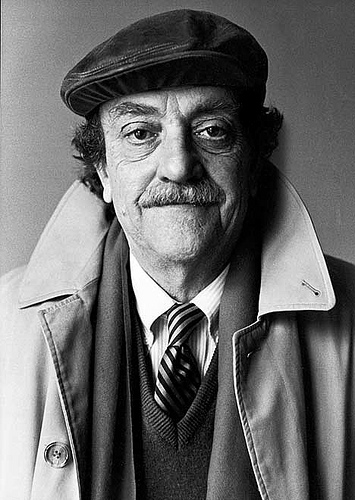

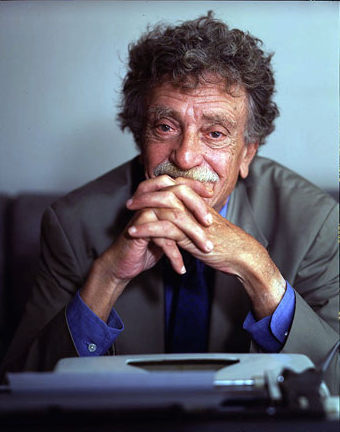

- Novelist Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., 1922

- Playwright Tom Stoppard (Tomáš Straüssler), 1937

PAGE SPONSOR

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. (November 11, 1922 – April 11, 2007) was a 20th century American writer. His works such as Cat's Cradle (1963), Slaughterhouse - Five (1969) and Breakfast of Champions (1973) blend satire, gallows humor and science fiction. He was known for his humanist beliefs and was honorary president of the American Humanist Association.

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. was born in Indianapolis, Indiana to third generation German - American parents, Kurt Vonnegut, Sr. and Edith Lieber. Both his father and his grandfather Bernard Vonnegut attended Massachusetts Institute of Technology and were architects in the Indianapolis firm of Vonnegut & Bohn. His great grandfather Clemens Vonnegut, Sr. was the founder of the Vonnegut Hardware Company, an Indianapolis institution. Vonnegut graduated from Shortridge High School in Indianapolis in May 1940 and matriculated into Cornell University that fall. Though majoring in chemistry, he was Assistant Managing Editor and Associate Editor of The Cornell Daily Sun. He was a member of the Delta Upsilon Fraternity, as was his father. While at Cornell, Vonnegut enlisted in the U.S. Army. The Army transferred him to the Carnegie Institute of Technology and the University of Tennessee to study mechanical engineering.

On Mothers' Day in 1944, when Vonnegut was 21, his mother committed suicide with sleeping pills.

Kurt Vonnegut's experience as a soldier and prisoner of war had a profound influence on his later work. As a private with the 423rd Infantry Regiment, 106th Infantry Division, Vonnegut was captured during the Battle of the Bulge on December 19, 1944, after the 106th was cut off from the rest of Courtney Hodges's First Army. "The other American divisions on our flanks managed to pull out: We were obliged to stay and fight. Bayonets aren't much good against tanks..." Imprisoned in Dresden, Vonnegut was chosen as a leader of the POWs because he spoke some German. After telling the German guards "...just what I was going to do to them when the Russians came..." he was beaten and had his position as leader taken away. While a prisoner, he witnessed the fire bombing of Dresden in February 1945 which destroyed most of the city.

Vonnegut was one of a group of American prisoners of war to survive the attack in an underground slaughterhouse meat locker used by the Germans as an ad hoc detention facility. The Germans called the building Schlachthof Fünf (Slaughterhouse Five) which the Allied POWs adopted as the name for their prison. Vonnegut said the aftermath of the attack was "utter destruction" and "carnage unfathomable." This experience was the inspiration for his famous novel, Slaughterhouse - Five, and is a central theme in at least six of his other books. In Slaughterhouse - Five he recalls that the remains of the city resembled the surface of the moon, and that the Germans put the surviving POWs to work, breaking into basements and bomb shelters to gather bodies for mass burial, while German civilians cursed and threw rocks at them. Vonnegut eventually remarked, "There were too many corpses to bury. So instead the Germans sent in troops with flamethrowers. All these civilians' remains were burned to ashes."

Vonnegut was liberated by Red Army troops in May 1945 at the Saxony - Czechoslovakian border. Upon returning to America, he was awarded a Purple Heart for what he called a "ludicrously negligible wound," later writing in Timequake that he was given the decoration after suffering a case of "frostbite".

After the war, Vonnegut attended the University of Chicago as a graduate student in anthropology and also worked at the City News Bureau of Chicago. He described his work there in the late 1940s in terms that could have been used by almost any other City Press reporter of any era: "Well, the Chicago City News Bureau was a tripwire for all the newspapers in town when I was there, and there were five papers, I think. We were out all the time around the clock and every time we came across a really juicy murder or scandal or whatever, they’d send the big time reporters and photographers, otherwise they’d run our stories. So that’s what I was doing, and I was going to university at the same time." Vonnegut admitted that he was a poor anthropology student, with one professor remarking that some of the students were going to be professional anthropologists and he was not one of them. According to Vonnegut in Bagombo Snuff Box, the university rejected his first thesis on the necessity of accounting for the similarities between Cubist painters and the leaders of late 19th Century Native American uprisings, saying it was "unprofessional." He left Chicago to work in Schenectady, New York, in public relations for General Electric, where his brother Bernard worked in the research department. Vonnegut was a technical writer, but was also known for writing well past his typical hours while working. While in Schenectady, Vonnegut lived in the tiny hamlet of Alplaus, located within the town of Glenville, just across the Mohawk River from the city of Schenectady. Vonnegut rented an upstairs apartment located along Alplaus Creek across the street from the Alplaus Volunteer Fire Department, where he was an active Volunteer Fire - Fighter for a few years. To this day, the apartment where Vonnegut lived for a brief time still has a desk at which he wrote many of his short stories; Vonnegut carved his name on its underside. The University of Chicago later accepted his novel Cat's Cradle as his thesis, citing its anthropological content, and awarded him the M.A. degree in 1971.

In the mid 1950s, Vonnegut worked very briefly for Sports Illustrated magazine, where he was assigned to write a piece on a racehorse that had jumped a fence and attempted to run away. After staring at the blank piece of paper on his typewriter all morning, he typed, "The horse jumped over the fucking fence," and left. On the verge of abandoning writing, Vonnegut was offered a teaching job at the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop. While he was there, Cat's Cradle became a best seller, and he began Slaughterhouse - Five, now considered one of the best American novels of the 20th century, appearing on the 100 best lists of Time magazine and the Modern Library.

Early in his adult life he moved to Barnstable, Massachusetts, a town on Cape Cod, where he managed the first Saab dealership established in the U.S.

The author's name appears in print as "Kurt Vonnegut, Jr." throughout the first half of his published writing career; beginning with the 1976 publication of Slapstick, he dropped the "Jr." and was simply billed as Kurt Vonnegut. His older brother, Bernard Vonnegut, was an atmospheric scientist at the University at Albany, SUNY, who discovered that silver iodide could be used for cloud seeding, the process of artificially stimulating precipitation.

After returning from World War II, Kurt Vonnegut married his childhood sweetheart, Jane Marie Cox, writing about their courtship in several of his short stories. In the 1960s they lived in Barnstable, Massachusetts, where for a while Vonnegut worked at a Saab dealership. The couple separated in 1970. He did not divorce Cox until 1979, but from 1970 Vonnegut lived with the woman who would later become his second wife, photographer Jill Krementz. Krementz and Vonnegut were married after the divorce from Cox was finalized.

He raised seven children: three from his first marriage; his sister Alice's three children, adopted by Vonnegut after her death from cancer; and a seventh, Lily, adopted with Krementz. His only biological son, Mark Vonnegut, a pediatrician, wrote the book The Eden Express: A Memoir of Insanity, about his experiences in the late 1960s and his major psychotic breakdown and recovery. Mark was named after Mark Twain, whom Vonnegut considered an American saint.

His daughter Edith ("Edie"), an artist, was named after Kurt Vonnegut's mother, Edith Lieber. She has had her work published in a book titled Domestic Goddesses and was once married to Geraldo Rivera. His youngest biological daughter, Nanette ("Nanny"), was named after Nanette Schnull, Vonnegut's paternal grandmother. She is married to realist painter Scott Prior and is the subject of several of his paintings, notably "Nanny and Rose".

Of Vonnegut's four adopted children, three are his nephews: James, Steven, and Kurt Adams; the fourth is Lily, a girl he adopted as an infant in 1982. James, Steven, and Kurt were adopted after a traumatic week in 1958, in which their father James Carmalt Adams was killed on September 15 in the Newark Bay rail crash when his commuter train went off the open Newark Bay bridge in New Jersey, and their mother — Kurt's sister Alice — died of cancer. In Slapstick, Vonnegut recounts that Alice's husband died two days before Alice herself, and her family tried to hide the knowledge from her, but she found out when an ambulatory patient gave her a copy of the New York Daily News a day before she herself died. The fourth and youngest of the boys, Peter Nice, went to live with a first cousin of their father in Birmingham, Alabama, as an infant. Lily is a singer and actress.

Jane Marie Cox later married Adam Yarmolinsky and wrote an account of the Vonneguts' life with the Adams children. It was published after her death as the book Angels Without Wings: A Courageous Family's Triumph Over Tragedy.

On November 11, 1999, an asteroid was named in Vonnegut's honor: 25399 Vonnegut.

On January 31, 2000, a fire destroyed the top story of his home. Vonnegut suffered smoke inhalation and was hospitalized in critical condition for four days. He survived, but his personal archives were destroyed. After leaving the hospital, he recuperated in Northampton, Massachusetts.

Vonnegut smoked unfiltered Pall Mall cigarettes, a habit he referred to as a "classy way to commit suicide".

Vonnegut died on April 11, 2007 after falling down a flight of stairs in his home and suffering massive head trauma.

Vonnegut's first short story, "Report on the Barnhouse Effect" appeared in the February 11, 1950 edition of Collier's (it has since been reprinted in his short story collection, Welcome to the Monkey House). His first novel was the dystopian novel Player Piano (1952), in which human workers have been largely replaced by machines. He continued to write short stories before his second novel, The Sirens of Titan, was published in 1959. Through the 1960s, the form of his work changed, from the relatively orthodox structure of Cat's Cradle (which in 1971 earned him a Master's Degree) to the acclaimed, semi - autobiographical Slaughterhouse - Five, given a more experimental structure by using time travel as a plot device.

These structural experiments were continued in Breakfast of Champions (1973), which includes many rough illustrations, lengthy non - sequiturs and an appearance by the author himself, as a deus ex machina.

- "This is a very bad book you're writing," I said to myself.

- "I know," I said.

- "You're afraid you'll kill yourself the way your mother did," I said.

- "I know," I said.

Deadeye Dick, although mostly set in the mid 20th century, foreshadows the turbulent times of contemporary America; it ends prophetically with the lines "You want to know something? We are still in the Dark Ages. The Dark Ages — they haven't ended yet." The novel explores themes of social isolation and alienation that are particularly relevant in the postmodern world. Society is seen as openly hostile or indifferent at best, and popular culture as superficial and excessively materialistic.

Vonnegut attempted suicide in 1984 and later wrote about this in several essays.

Breakfast of Champions became one of his best selling novels. It includes, in addition to the author himself, several of Vonnegut's recurring characters. One of them, science fiction author Kilgore Trout, plays a major role and interacts with the author's character.

In 1974, Venus on the Half - Shell, a book by Philip José Farmer in a style similar to that of Vonnegut and attributed to Kilgore Trout, was published. This caused some confusion among readers, as for some time many assumed that Vonnegut wrote it; when the truth of its authorship came out, Vonnegut was reported as being "not amused". In an issue of the semi - prozine The Alien Critic / Science Fiction Review, published by Richard E. Geis, Farmer claimed to have received an angry, obscenity laden telephone call from Vonnegut about it.

In addition to recurring characters, there are also recurring themes and ideas. One of them is ice - nine (a central wampeter in his novel Cat's Cradle).

Although many of his novels involved science fiction themes, they were widely read and reviewed outside the field, not least due to their anti - authoritarianism. For example, in his seminal short story "Harrison Bergeron" egalitarianism is rigidly enforced by overbearing state authority, engendering horrific repression.

In much of his work, Vonnegut's own voice is apparent, often filtered through the character of science fiction author Kilgore Trout (whose name is based on that of real life science fiction writer Theodore Sturgeon). It is characterized by wild leaps of imagination and a deep cynicism, tempered by humanism. In the foreword to Breakfast of Champions, Vonnegut wrote that as a child, he saw men with locomotor ataxia, and it struck him that these men walked like broken machines; it followed that healthy people were working machines, suggesting that humans are helpless prisoners of determinism. Vonnegut also explored this theme in Slaughterhouse - Five, in which protagonist Billy Pilgrim "has come unstuck in time" and has so little control over his own life that he cannot even predict which part of it he will be living through from minute to minute. Vonnegut's well-known phrase "So it goes", used ironically in reference to death, also originated in Slaughterhouse - Five. "Its combination of simplicity, irony, and rue is very much in the Vonnegut vein."

With the publication of his novel Timequake in 1997, Vonnegut announced his retirement from writing fiction. He continued to write for the magazine In These Times, where he was a senior editor, until his death in 2007, focusing on subjects ranging from contemporary U.S. politics to simple observational pieces on topics such as a trip to the post office. In 2005, many of his essays were collected in a new bestselling book titled A Man Without a Country, which he insisted would be his last contribution to letters.

An August 2006 article reported:

- He has stalled finishing his highly anticipated novel If God Were Alive Today — or so he claims. "I've given up on it... It won't happen... The Army kept me on because I could type, so I was typing other people's discharges and stuff. And my feeling was, 'Please, I've done everything I was supposed to do. Can I go home now?' That's what I feel right now. I've written books. Lots of them. Please, I've done everything I'm supposed to do. Can I go home now?"

The April 2008 issue of Playboy featured the first published excerpt from Armageddon in Retrospect, the first posthumous collection of Vonnegut's work. The book itself was published in the same month. It included never before published short stories by the writer and a letter that was written to his family during World War II when Vonnegut was captured as a prisoner of war. The book also contains drawings by Vonnegut and a speech he wrote shortly before his death. The introduction was written by his son, Mark Vonnegut.

Vonnegut also taught at Harvard University, where he was a lecturer in English, and the City College of New York, where he was a Distinguished Professor.

Vonnegut's work as a graphic artist began with his illustrations for Slaughterhouse - Five and developed with Breakfast of Champions, which included numerous felt - tip pen illustrations. Later in his career, he became more interested in artwork, particularly silk - screen prints, which he pursued in collaboration with Joe Petro III.

In 2004, Vonnegut participated in the project The Greatest Album Covers That Never Were, for which he created an album cover for Phish called Hook, Line and Sinker, which has been included in a traveling exhibition for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Vonnegut was deeply influenced by early Socialist labor leaders, especially Indiana natives Powers Hapgood and Eugene V. Debs, and he frequently quoted them in his work. He named characters after both Debs (Eugene Debs Hartke in Hocus Pocus and Eugene Debs Metzger in Deadeye Dick) and Russian Communist leader Leon Trotsky (Leon Trotsky Trout in Galápagos). He was a lifetime member of the American Civil Liberties Union and was featured in a print advertisement for them.

In 1968, he signed the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War.

Vonnegut frequently addressed moral and political issues but rarely dealt with specific political figures until after his retirement from fiction. Though the downfall of Walter Starbuck, a minor Nixon administration bureaucrat who is the narrator and main character in Jailbird (1979), would not have occurred but for the Watergate scandal, the focus is not on the administration. His collection God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian referenced controversial assisted suicide proponent Jack Kevorkian.

With his columns for In These Times, he began an attack on the Bush administration and the Iraq war. "By saying that our leaders are power - drunk chimpanzees, am I in danger of wrecking the morale of our soldiers fighting and dying in the Middle East?" he wrote. "Their morale, like so many bodies, is already shot to pieces. They are being treated, as I never was, like toys a rich kid got for Christmas." In These Times quoted him as saying "The only difference between Hitler and Bush is that Hitler was elected." In a 2003 interview Vonnegut said, "I myself feel that our country, for whose Constitution I fought in a just war, might as well have been invaded by Martians and body snatchers. Sometimes I wish it had been. What has happened, though, is that it has been taken over by means of the sleaziest, low - comedy, Keystone Cops - style coup d’etat imaginable. And those now in charge of the federal government are upper - crust C-students who know no history or geography, plus not - so - closeted white supremacists, aka 'Christians,' and plus, most frighteningly, psychopathic personalities,or 'PPs.'" When asked how he was doing at the start of a 2003 interview, he replied: "I'm mad about being old and I'm mad about being American. Apart from that, OK."

He did not regard the 2004 election with much optimism; speaking of Bush and John Kerry, he said that "no matter which one wins, we will have a Skull and Bones President at a time when entire vertebrate species, because of how we have poisoned the topsoil, the waters and the atmosphere, are becoming, hey presto, nothing but skulls and bones."

In 2005, Vonnegut was interviewed by David Nason for The Australian. During the course of the interview Vonnegut was asked his opinion of modern terrorists, to which he replied, "I regard them as very brave people." When pressed further Vonnegut also said that "They [suicide bombers] are dying for their own self - respect. It's a terrible thing to deprive someone of their self - respect. It's [like] your culture is nothing, your Race is nothing, you're nothing ... It is sweet and noble — sweet and honorable I guess it is — to die for what you believe in." (This last statement is a reference to the line "Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori" ["it is sweet and fitting to die for one's country"] from Horace's Odes, or possibly to Wilfred Owen's ironic use of the line in his Dulce Et Decorum Est.) Nason took offense at Vonnegut's comments and characterized him as an old man who "doesn't want to live any more ... and because he can't find anything worthwhile to keep him alive, he finds defending terrorists somehow amusing." Vonnegut's son, Mark, responded to the article by writing an editorial to the Boston Globe in which he explained the reasons behind his father's "provocative posturing" and stated that "If these commentators can so badly misunderstand and underestimate an utterly unguarded English speaking 83 year old man with an extensive public record of saying exactly what he thinks, maybe we should worry about how well they understand an enemy they can't figure out what to call."

A 2006 interview with Rolling Stone stated, " ... it's not surprising that he disdains everything about the Iraq War. The very notion that more than 2,500 U.S. soldiers have been killed in what he sees as an unnecessary conflict makes him groan. 'Honestly, I wish Nixon were president,' Vonnegut laments. 'Bush is so ignorant.' "

Though

he was a dissident to the end, Vonnegut held a bleak view on the power

of artists to effect change. "During the Vietnam War," he told an

interviewer in 2003, "every respectable artist in this country was

against the war. It was like a laser beam. We were all aimed in the same

direction. The power of this weapon turns out to be that of a custard

pie dropped from a stepladder six feet high."

Vonnegut was descended from a family of German freethinkers, who were skeptical of "conventional religious beliefs." His great grandfather Clemens Vonnegut had authored a freethought book titled Instruction in Morals, as well as an address for his own funeral in which he denied the existence of God, an afterlife, and Christian doctrines about sin and salvation. Kurt Vonnegut reproduced his great grandfather's funeral address in his book Palm Sunday, and identified these freethought views as his "ancestral religion," declaring it a mystery as to how it was passed on to him.

Vonnegut described himself variously as a skeptic, freethinker, humanist, Unitarian Universalist, agnostic, and atheist. He disbelieved in the supernatural, considered religious doctrine to be "so much arbitrary, clearly invented balderdash," and believed people were motivated by loneliness to join religions.

Vonnegut considered humanism to be a modern - day form of freethought, and advocated it in various writings, speeches and interviews. His ties to organized humanism included membership as a Humanist Laureate in the Council for Secular Humanism's International Academy of Humanism. In 1992, the American Humanist Association named him the Humanist of the Year. Vonnegut went on to serve as honorary president of the American Humanist Association (AHA), having taken over the position from his late colleague Isaac Asimov, and serving until his own death in 2007. In a letter to AHA members, Vonnegut wrote: "I am a humanist, which means, in part, that I have tried to behave decently without expectations of rewards or punishments after I am dead."

Vonnegut was at one time a member of a Unitarian congregation. Palm Sunday reproduces a sermon he delivered to the First Parish Unitarian Church in Cambridge, Massachusetts, concerning William Ellery Channing, who was a principal founder of Unitarianism in the United States. In 1986, Vonnegut spoke to a gathering of Unitarian Universalists in Rochester, New York, and the text of his speech is reprinted in his book Fates Worse Than Death. Also reprinted in that book was a "mass" by Vonnegut, which was performed by a Unitarian Universalist choir in Buffalo, New York. Vonnegut identified Unitarianism as the religion that many in his freethinking family turned to when freethought and other German "enthusiasms" became unpopular in the United States during the World Wars. Vonnegut's parents were married by a Unitarian minister, and his son had at one time aspired to become a Unitarian minister.

Vonnegut's views on religion were unconventional and nuanced. While rejecting the divinity of Jesus, he was nevertheless an ardent admirer, and believed that Jesus's Beatitudes informed his own humanist outlook. While he often identified himself as an agnostic or atheist, he also frequently spoke of God. Despite

describing freethought, humanism and agnosticism as his "ancestral

religion," and despite being a Unitarian, he also spoke of himself as

being irreligious. A press release by the American Humanist Association described him as "completely secular."

In his book Bagombo Snuff Box: Uncollected Short Fiction, Vonnegut listed eight rules for writing a short story:

- Use the time of a total stranger in such a way that he or she will not feel the time was wasted.

- Give the reader at least one character he or she can root for.

- Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.

- Every sentence must do one of two things — reveal character or advance the action.

- Start as close to the end as possible.

- Be a Sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them — in order that the reader may see what they are made of.

- Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia.

- Give your readers as much information as possible as soon as possible. To hell with suspense. Readers should have such complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves, should cockroaches eat the last few pages.

Vonnegut qualifies the list by adding that Flannery O'Connor broke all these rules except the first, and that great writers tend to do that. He wrote an earlier version of writing tips that was even more straightforward and contained only seven rules (though it advised using Elements of Style for more indepth advice).

In "The Sexual Revolution", Chapter 18 of his book Palm Sunday, Vonnegut grades his own works. He states that the grades "do not place me in literary history" and that he is comparing "myself with myself." The grades are as follows:

- Player Piano: B

- The Sirens of Titan: A

- Mother Night: A

- Cat's Cradle: A-plus

- God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater: A

- Slaughterhouse-Five: A-plus

- Welcome to the Monkey House: B-minus

- Happy Birthday, Wanda June: D

- Breakfast of Champions: C

- Slapstick: D

- Jailbird: A

- Palm Sunday: C

Sir Tom Stoppard (born Tomáš Straüssler 3 July 1937) is a British playwright, knighted in 1997. He has written prolifically for TV, radio, film and stage, finding prominence with plays such as Arcadia, The Coast of Utopia, Every Good Boy Deserves Favour, Professional Foul, The Real Thing, and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. He co-wrote the screenplays for Brazil and Shakespeare in Love and has won one Academy Award and four Tony Awards. Themes of human rights, censorship and political freedom pervade his work along with exploration of linguistics and philosophy. Stoppard has been a key playwright of the National Theatre and is one of the most internationally performed dramatists of his generation.

In

1939, Stoppard left Czechoslovakia as a child refugee, fleeing imminent

Nazi occupation. He settled with his family in Britain after the war,

in 1946. After being educated at schools in Nottingham and Yorkshire,

Stoppard became a journalist, a drama critic and then, in 1960, a

playwright. He has been married twice, to Josie Ingle (1965 – 1972) and Miriam Stoppard (1972 – 1992), and has two sons from each marriage, one of whom is actor Ed Stoppard.

Stoppard was born Tomáš Straüssler, in Zlín, a "Shoe Town", in the Moravia region of Czechoslovakia. He was the son of Martha Beckova and Eugen Straüssler, a doctor with the Bata shoe company. Both parents were Jewish, though neither practicing. Just before the German occupation of Czechoslovakia, the town's patron, Thomas J. Bata, helped re-post his Jewish employees, mostly physicians, to various branches of his firm all over the world. On 15 March 1939, the day that the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia, the Straüssler family fled to Singapore, one of the places Bata had a company.

Before the Japanese occupation of Singapore, the two sons and their mother were sent on to Australia. Stoppard's father remained in Singapore as a British army volunteer, knowing that, as a doctor, he would be needed in its defense. His father died when Stoppard was four years old. In the book Tom Stoppard in conversation, Stoppard tells how his father died in Japanese captivity, a prisoner of war although Straüssler is also commonly reported to have drowned on board a ship bombed by Japanese forces.

From there, in 1941, when Tomas was five, the three were evacuated to Darjeeling in India. The boys attended the Mount Hermon American multi - racial school where Tomas became Tom and his brother Petr became Peter.

In 1945, his mother Martha married British army major Kenneth Stoppard, who gave the boys his English surname and, in 1946, after the war, moved the family to England. His stepfather believed strongly that "to be born an Englishman was to have drawn first prize in the lottery of life", telling his small stepson: "Don't you realize that I made you British?" setting up Stoppard's desire as a child to become "an honorary Englishman". "I fairly often find I'm with people who forget I don't quite belong in the world we're in", he says. "I find I put a foot wrong – it could be pronunciation, an arcane bit of English history – and suddenly I'm there naked, as someone with a pass, a press ticket." This is reflected in his characters, he notes, who are "constantly being addressed by the wrong name, with jokes and false trails to do with the confusion of having two names". Stoppard attended the Dolphin School in Nottinghamshire, and later completed his education at Pocklington School in East Riding, Yorkshire, which he hated.

Stoppard left school at seventeen and began work as a journalist for Western Daily Press in Bristol, never receiving a university education, having taken against the idea. Years

later he came to regret not going to university, but loved his time as a

journalist and felt passionately about his career at the time. He remained at the paper from 1954 until 1958, when the Bristol Evening World offered

Stoppard the position of feature writer, humor columnist, and

secondary drama critic, which took Stoppard into the world of theater.

At the Bristol Old Vic – at the time a well regarded regional repertory company – Stoppard formed friendships with director John Boorman and actor Peter O'Toole early

in their careers. In Bristol, he became known more for his strained

attempts at humor and unstylish clothes than for his writing.

Stoppard wrote short radio plays in 1953-4 and by 1960 he had completed his first stage play, A Walk on the Water, which was later re-titled Enter a Free Man (1968). He noted that the work owed much to Robert Bolt's Flowering Cherry and Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman. Within a week after sending A Walk on the Water to an agent, Stoppard received his version of the "Hollywood - style telegrams that change struggling young artists' lives." His first play was optioned, staged in Hamburg, then broadcast on British Independent Television in 1963. From September 1962 until April 1963, Stoppard worked in London as a drama critic for Scene magazine, writing reviews and interviews both under his name and the pseudonym William Boot (taken from Evelyn Waugh's Scoop). In 1964, a Ford Foundation grant enabled Stoppard to spend 5 months writing in a Berlin mansion, emerging with a one act play titled Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Meet King Lear, which later evolved into his Tony winning play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. In the following years, Stoppard produced several works for radio, television and the theater, including "M" is for Moon Among Other Things (1964), A Separate Peace (1966) and If You're Glad I'll Be Frank (1966). On 11 April 1967 — following acclaim at the 1966 Edinburgh Festival — the opening of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead in a National Theatre production at the Old Vic made Stoppard an overnight success.Jumpers (1972) places a professor of moral philosophy in a murder mystery thriller along side a slew of radical gymnasts and Travesties (1974), explored the 'Wildean' possibilities arising from the fact that Lenin, Joyce, and Tristan Tzara had all been in Zurich during the First World War. In his early years, he also wrote extensively for BBC radio, often introducing surrealist themes. He has also adapted many of his stage works for radio, film and television winning extensive awards and honors from the start of his career.

Stoppard has written one novel, Lord Malquist and Mr Moon (1966), set in contemporary London. Its cast includes the 18th century figure of the dandified Malquist and his ineffectual Boswell, Moon, and also cowboys, a lion (banned from the Ritz) and a donkey borne Irishman claiming to be the Risen Christ.

In the 1980s, in addition to writing his own works, Stoppard translated many plays into English, including works by Sławomir Mrożek, Johann Nestroy, Arthur Schnitzler, and Václav Havel. It was at this time that Stoppard became influenced by the works of Polish and Czech absurdists. He has been co-opted into the Outrapo group, a far - from - serious French movement to improve actors' stage technique through science.

Stoppard has also co-written screenplays including Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Spielberg states that though Stoppard was uncredited, "he was responsible for almost every line of dialogue in the film". It is also rumored that Stoppard worked on Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith, though again Stoppard received no official or formal credit in this role. He worked in a similar capacity with Tim Burton on his film Sleepy Hollow. In 2008, Stoppard was voted the number 76 on the Time 100, Time magazine's list of the most influential people in the world.

Stoppard serves on the advisory board of the magazine Standpoint, and was instrumental in its foundation, giving the opening speech at its launch.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966–7) was Stoppard's first major play to gain recognition. The story of Hamlet, as told from the viewpoint of two courtiers echoes Beckett in its double act repartee, existential themes and language play. "Stoppardian" became a term describing works using wit and comedy while addressing philosophical concepts. Critic Dennis Kennedy notes "It established several characteristics of Stoppard's dramaturgy: his word - playing intellectuality, audacious, paradoxical, and self - conscious theatricality, and preference for reworking pre - existing narratives... Stoppard's plays have been sometimes dismissed as pieces of clever showmanship, lacking in substance, social commitment, or emotional weight. His theatrical surfaces serve to conceal rather than reveal their author's views, and his fondness for towers of paradox spirals away from social comment. This is seen most clearly in his comedies The Real Inspector Hound (1968) and After Magritte (1970), which create their humor through highly formal devices of reframing and juxtaposition." Stoppard himself went so far as to declare "I must stop compromising my plays with this whiff of social application. They must be entirely untouched by any suspicion of usefulness." He acknowledges that he started off "as a language nerd", primarily enjoying linguistic and ideological playfulness, feeling early in his career that journalism was far better suited for presaging political change, than playwriting.

The accusations of favoring intellectuality over political commitment or commentary were met with a change of tack, as Stoppard produced increasingly socially engaged work. From 1977, he became personally involved with human rights issues, in particular with the situation of political dissidents in Central and Eastern Europe. In February 1977, he visited the Soviet Union and several Eastern European countries with a member of Amnesty International. In June, Stoppard met Vladimir Bukovsky in London and traveled to Czechoslovakia (then under communist control), where he met dissident playwright and future president Václav Havel, whose writing he greatly admires. Stoppard became involved with Index on Censorship, Amnesty International, and the Committee Against Psychiatric Abuse and wrote various newspaper articles and letters about human rights. He was also instrumental in translating Havel's works into English. Every Good Boy Deserves Favour (1977), ‘a play for actors and orchestra’ was based on a request by composer André Previn; inspired by a meeting with a Russian exile. This play as well as Dogg's Hamlet, Cahoot's Macbeth (1979), The Coast of Utopia (2002), Rock ‘n’ Roll (2006), and two works for television Professional Foul (1977) and Squaring the Circle (1984) all concern themes of censorship, rights abuses, and state repression.

Stoppard's later works have sought greater inter - personal depths, whilst maintaining their intellectual playfulness. Stoppard acknowledges that around 1982 he moved away from the "argumentative" works and more towards plays of the heart, as he became "less shy" about emotional openness. Discussing the later integration of heart and mind in his work, he commented "I think I was too concerned when I set off, to have a firework go off every few seconds... I think I was always looking for the entertainer in myself and I seem to be able to entertain through manipulating language... [but] it's really about human beings, it's not really about language at all." He was inspired by a Trevor Nunn production of Gorky's Summerfolk to write more a trilogy of more 'human' plays: The Real Thing (1982) uses a meta - theatrical structure to explore the suffering that adultery can produce and The Invention of Love (1997) also investigates the pain of passion. Arcadia (1993) explores the meeting of chaos theory, historiography, and landscape gardening.

He

has commented that he loves the medium of theater for how 'adjustable'

it is at every point, how unfrozen it is, continuously growing and

developing through each rehearsal, free from the text. His experience of

writing for film is similar, offering the liberating opportunity to

'play God', in control of creative reality. It often takes four to five

years from the first idea of a play to staging, taking pains to be as

profoundly accurate in his research as he can be.

Stoppard has been married twice, to Josie Ingle (1965 – 1972), a nurse, and to Miriam Stoppard (née Stern and subsequently Miriam Moore - Robinson, 1972 – 1992), whom he left to begin a relationship with actress Felicity Kendal. He has two sons from each marriage: Oliver Stoppard, Barnaby Stoppard, the actor Ed Stoppard and Will Stoppard, who is married to violinist Linzi Stoppard.

In 1979, the year of Margaret Thatcher's election, Stoppard noted to Paul Delaney: "I'm a conservative with a small c. I am a conservative in politics, literature, education and theatre." In 2007, Stoppard described himself as a "timid libertarian".

Stoppard sat for sculptor Alan Thornhill, and a bronze head is now in public collection, situated with the Stoppard papers in the reading room of the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. The terracotta remains in the collection of the artist in London. The correspondence file relating to the Stoppard bust is held in the archive of the Henry Moore Foundation's Henry Moore Institute in Leeds.

The Tom Stoppard Prize was created in 1983 (in Stockholm, under the Charter 77 Foundation) and is awarded to authors of Czech origin.

Stoppard's mother died in 1996. The family had not talked about their history and neither brother knew what had happened to the family left behind in Czechoslovakia. In the early 1990s, with the fall of communism, Stoppard found out that all four of his grandparents had been Jewish and had died in Terezin, Auschwitz and other camps, along with three of his mother's sisters. In 1998, following the deaths of his parents he went back, for the first time, to Zlín after 60 years. He has expressed grief both for a lost father and a missing past, but he has no sense of being a survivor, at whatever remove. "I feel incredibly lucky not to have had to survive or die. It's a conspicuous part of what might be termed a charmed life."

Stoppard, Kevin Spacey, Jude Law, and others, joined protests against the regime of Alexander Lukashenko in March 2011, showing their support for the Belarusian democracy movement.