<Back to Index>

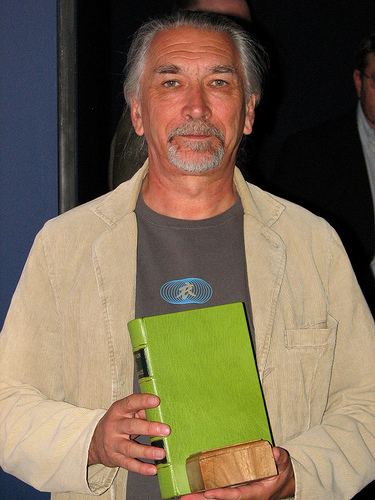

- Writer Paul Benjamin Auster, 1947

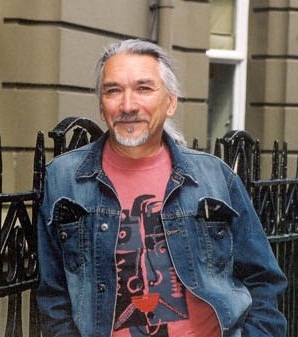

- Writer and Critic M. John Harrison, 1945

PAGE SPONSOR

Paul Benjamin Auster (born February 3, 1947) is an American author known for works blending absurdism, existentialism, crime fiction and the search for identity and personal meaning in works such as The New York Trilogy (1987), Moon Palace (1989), The Music of Chance (1990), The Book of Illusions (2002) and The Brooklyn Follies (2005).

Auster was born in Newark, New Jersey, to Jewish middle class parents of Polish descent, Samuel and Queenie Auster. He grew up in South Orange, New Jersey and graduated from Columbia High School in adjoining Maplewood. After graduating from Columbia University in 1970, he moved to Paris, France, where he earned a living translating French literature. Since returning to the U.S. in 1974, he has published poems, essays, novels of his own as well as translations of French writers such as Stéphane Mallarmé and Joseph Joubert.

He and his second wife, writer Siri Hustvedt, were married in 1981, and they live in Brooklyn. Together they have one daughter, Sophie Auster. Previously, Auster was married to the acclaimed writer Lydia Davis. They had one son together, Daniel Auster.

He is also the Vice - President of PEN American Center.

Following his acclaimed debut work, a memoir entitled The Invention of Solitude, Auster gained renown for a series of three loosely connected detective stories published collectively as The New York Trilogy. These books are not conventional detective stories organized around a mystery and a series of clues. Rather, he uses the detective form to address existential issues and questions of identity, space, language and literature, creating his own distinctively postmodern (and critique of postmodernist) form in the process. Comparing the two works, Auster said, "I believe the world is filled with strange events. Reality is a great deal more mysterious than we ever give it credit for. In that sense, the Trilogy grows directly out of The Invention of Solitude."

The

search for identity and personal meaning has permeated Auster's later

publications, many of which concentrate heavily on the role of

coincidence and random events (The Music of Chance) or increasingly, the relationships between men and their peers and environment (The Book of Illusions, Moon Palace).

Auster's heroes often find themselves obliged to work as part of

someone else's inscrutable and larger - than - life schemes. In 1995, Auster

wrote and co-directed the films Smoke (which won him the Independent Spirit Award for Best First Screenplay) and Blue in the Face. Auster's more recent works, Oracle Night (2003), The Brooklyn Follies (2005) and the novella Travels in the Scriptorium have also met critical acclaim.

According to a dissertation by Heiko Jakubzik at the University of Heidelberg, two central influences in Paul Auster's writing are Jacques Lacan's psychoanalysis and the American transcendentalism of the early to middle 19th century, namely amongst others Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

In short Lacan's theory declares that we enter the world through words. We observe the world through our senses but the world we sense is structured (mediated) in our mind through language. Thus our subconscious is also structured as a language. This leaves us with a sense of anomaly. We can only perceive the world through language, but we have the feeling of something missing. This is the sense of being outside language. The world can only be constructed through language but it always leaves something uncovered, something that cannot be told or be thought of, it can only be sensed. This can be seen as one of the central themes of Paul Auster's writing.

Lacan is considered to be one of the key figures of French poststructuralism. Some academics are keen to discern traces of other poststructuralist philosophers throughout Auster's oeuvre - mainly Jacques Derrida, Jean Baudrillard and Michel de Certeau - although Auster himself has claimed to find such philosophies 'unreadable'.

The transcendentalists believe that the symbolic order of civilization separated us from the natural order of the world. By moving into nature - like Thoreau in Walden - it would be possible to return to this natural order.

The common factor of both ideas is the question of the meaning of symbols for human beings. Auster's protagonists are often writers who establish meaning in their lives through writing, and they try to find their place within the natural order to be able to live within "civilization" again.

Edgar Allan Poe, Samuel Beckett, and Herman Melville have also had a strong influence on Auster's writing. Not only do their characters reappear in Auster's work (like William Wilson in City of Glass or Hawthorne's Fanshawe in The Locked Room, both from The New York Trilogy), Auster also uses variations on the themes of these writers.

Paul Auster's reappearing subjects are:

- coincidence

- frequent portrayal of an ascetic life

- a sense of imminent disaster

- obsessive writer as central character/narrator

- loss of the ability to understand

- loss of language

- depiction of daily and ordinary life

- failure

- absence of a father

- writing / story telling, metafiction

- intertextuality

- American History

- American Space

Instances of coincidence can be found throughout Auster's work. Auster himself claims that people are so influenced by the continuity among them that they do not see the elements of coincidence, inconsistency and contradiction in their own lives:

| “ | This idea of contrasts, contradictions, paradox, I think, gets very much to the heart of what novel writing is for me. It's a way for me to express my own contradictions. | ” |

Failure in Paul Auster's works is not just the opposite of the happy ending. In Moon Palace and The Book of Illusions it comes from the individual's uncertainty about the status of his own identity. The protagonists start a search for their own identity and reduce their life to the absolute minimum. From this zero point they gain new strength and start their new life and they are also able to regain contact with their surroundings. A similar development can also be seen in City of Glass and The Music of Chance.

Failure in this context is not the "nothing" - it is the beginning of something all new.

Auster's protagonists often go through a process that reduces their support structure to an absolute minimum: They sever all contact with family and friends, go hungry and lose or give away all their belongings. Out of this state of "nothingness" they either acquire new strength to reconnect with the world or they fail and disappear for good.

| “ | But in the end, he manages to resolve the question for himself - more or less. He finally comes to accept his own life, to understand that no matter how bewitched and haunted he is, he has to accept reality as it is, to tolerate the presence of ambiguity within himself. | ” |

—Paul Auster about the protagonist of The Locked Room, quoted in Martin Klepper, Pynchon, Auster, DeLillo. | ||

"Over the past twenty - five years," opined Michael Dirda in The New York Review of Books in 2008, "Paul Auster has established one of the most distinctive niches in contemporary literature." Dirda has also extolled his loaded virtues in The Washington Post:

Ever since City of Glass, the first volume of his New York Trilogy, Auster has perfected a limpid, confessional style, then used it to set disoriented heroes in a seemingly familiar world gradually suffused with mounting uneasiness, vague menace and possible hallucination. His plots — drawing on elements from suspense stories, existential récit and autobiography — keep readers turning the pages, but sometimes end by leaving them uncertain about what they've just been through.

Respected literary critic James Wood, however, offers Auster little praise in his piece "Shallow Graves" in the November 30, 2009, issue of The New Yorker:

What Auster often gets instead is the worst of both worlds: fake realism and shallow skepticism. The two weaknesses are related. Auster is a compelling storyteller, but his stories are assertions rather than persuasions. They declare themselves; they hound the next revelation. Because nothing is persuasively assembled, the inevitable postmodern disassembly leaves one largely untouched. (The disassembly is also grindingly explicit, spelled out in billboard - size type.) Presence fails to turn into significant absence, because presence was not present enough.

Michael John Harrison (born 26 July 1945), known primarily by his pen name M. John Harrison, is an English author and critic. His work includes the Viriconium sequence of novels and short stories, (1982), Climbers (1989), and the Kefahuchi Tract series which begins with Light (2002). He currently resides in London.

Harrison was born in Rugby, Warwickshire, in 1945. In an interview with Zone magazine, Harrison says "I liked anything bizarre, from being about four years old. I started on Dan Dare and worked up the Absurdists. At 15 you could catch me with a pile of books that contained an Alfred Bester, a Samuel Beckett, a Charles Williams, the two or three available J.G. Ballards, On the Road by Jack Kerouac, some Keats, some Alan Ginsberg, maybe a Thorne Smith. I've always been pick 'n' mix: now it's a philosophy. ("Disillusioned by the Actual: An Interview with M. John Harrison" by Patrick Hudson).

According

to the jacket blurb of his first novel, he was treated to a technical

education which didn't stick; he worked at various times as a groom

(North Warwicks Hunt), a teacher, and a clerk for a masonic charity

outfit; his hobbies included dwarfs, electric guitars and writing pastiches of H.H. Munro.

His first short story was published in 1966 by Kyril Bonfiglioli at Science Fantasy magazine, on the strength of which he moved to London. He there met Michael Moorcock, who was editing new Worlds magazine.

From 1968 to 1975 he was literary editor of the New Wave science fiction magazine New Worlds. He was central to the New Wave movement which also included writers such as Norman Spinrad, Barrington Bayley and Thomas M. Disch. As reviewer for New Worlds he often used the pseudonym "Joyce Churchill" and was trenchantly critical of many works and writers published under the rubric of science fiction.

Amongst his works of that period are three stories utilizing the Jerry Cornelius character invented by Michael Moorcock. (These stories do not appear in any of Harrison's own collections but do appear in the Nature of the Catastrophe and New Nature of the Catastophe published under Moorcock's name.) Other early stories appearing as from 1966, featured in anthologies such as such as New Writings in SF edited by John Carnell, and in magazines such as Transatlantic Review and the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

Harrison later moved to Manchester and was a regular contributor to New Manchester Review (1978 – 79). David Britton and Michael Butterworth of Savoy Books employed him to write in their basement, commissioning what eventually became the novel In Viriconium.

His early novels, the dystopian The Committed Men, The Pastel City and the revisionist space opera The Centauri Device have been reprinted several times. The latter was included in the SF Masterworks series, though Harrison is reputedly not fond of it. His work is profoundly leftist and committed to depicting alienated characters in the world of late Capitalism. Indeed, in interviews, M. John Harrison has described himself as an anarchist, and Michael Moorcock wrote in an essay entitled "Starship Stormtroopers" that, "His books are full of anarchists -- some of them very bizarre like the anarchist aesthetes of The Centauri Device."

Between 1976 and 1986 he lived in the Peak District, where his interest in rock climbing led to the autobiographical novel Climbers (1989), the first novel to receive the Boardman Tasker Prize for Mountain Literature. Harrison also ghost wrote the autobiography of one of Britain's best rock climbers, Ron Fawcett (Fawcett on Rock, 1987, as by Mike Harrison). Harrison has repeatedly affirmed in print the importance of rock climbing for his writing as an attempt to grapple with reality and its implications, which he had lost sight of while writing fantasy. The difference in his approach can be observed in the stylistic differences between the first novel of the Viriconium sequence The Pastel City and the second, A Storm of Wings.

In Viriconium was nominated for the Guardian Fiction Prize in 1982. The Viriconium sequence, influenced in its imagery by the poems of T.S. Eliot, consists of three novels and various short stories; its most complete version is the 2005 omnibus simply titled Viriconium which includes all the connected novels and most of the short stories. The graphic novel The Luck in the Head adapts one of his short works set in the sequence.

Subsequent novels and short stories, such as The Course of the Heart (1991) and "Empty" (1993), were set between London and the Peak District. They have a lyrical style and a strong sense of place, and take their tension from characteristically conflicting veins of mysticism and realism. The Course of the Heart deals in part with a magical experiment gone wrong, and with an imaginary country which may exist at the heart of Europe, as well as Gnostic themes.

The novel Signs of Life (1996) is a romantic thriller which explores concerns about genetics and biotechnology amidst the turmoil of what might be termed a three way love affair between its central characters.

Beginning with The Wild Road in 1996, he co-wrote four linked fantasies about cats with Jane Johnson, under the pseudonym "Gabriel King".

Harrison won the Richard Evans Award in 1999 (named after the near legendary figure of UK publishing) given to the author who has contributed significantly to the SF genre without concomitant commercial success.

In 2003 Harrison was on the jury of the Michael Powell Award at the Edinburgh International Film Festival.

His science fiction novel Light was co-winner of the James Tiptree, Jr. Award in 2003. Its sequel, Nova Swing (2006), won the Arthur C. Clarke Award in 2007 and the Philip K. Dick Award in 2008.

Harrison has collaborated on short stories with Simon Ings and with Simon Pummel on the short film Ray Gun Fun (1998). His work has been seen by some as forming part of the movement dubbed the New Weird, along with writers such as China Mieville, though Harrison himself resists being labelled as part of any literary movement.

He recently provided material for performance by Barbara Campbell (1001 Nights Cast, 2007, 2008) and Kate McIntosh (Loose Promise, 2007).

He has taught creative writing courses in Devon and Wales, focusing on landscape and autobiography, with Adam Lively and the travel writer James Perrin. Since 1991, Harrison has reviewed fiction and nonfiction for The Guardian, the Daily Telegraph, the Times Literary Supplement and the New York Times.

His short stories have appeared in magazines as diverse as Conjunctions ("Entertaining Angels Unawares", Fall issue 2002), the Independent on Sunday ("Cicisbeo", 2003), the Times Literary Supplement ("Science and the Arts", 1999) and Women's Journal ("Old Women", 1982). They were collected in Travel Arrangements (2000) and Things That Never Happen (2002).

In 2009, Harrison shared (with Sarah Hall (writer) and Nicholas Royle) the judging of the Manchester Fiction Prize.

On 6 June 2009, Harrison wrote on his official blog that he has three major works in progress. These are: "(a) a third Light novel, which will collide A.E. van Vogt with all sorts of other unlikely people" - this novel has been announced as Pearlant,

for publication in April 2012; (b) "a collection of short stories, some

of which will be voiced in a familiar way, some of which won’t;" and

(c) "something I would describe as a literary seaside concept - horror

novel if four - word descriptions weren’t a betrayal of everything I stand

for…"

Harrison is stylistically an Imagist and his early work relies heavily on the use of strange juxtapositions characteristic of absurdism. His work has been acclaimed by writers including Angela Carter, Neil Gaiman, China Miéville, and Clive Barker, who has referred to him as "a blazing original". In a Locus magazine interview, Harrison describes his work as "a deliberate intention to illustrate human values by describing their absence."

Many of Harrison's novels include expansions or reworkings of previously published short stories. For instance, "The Ice Monkey" (title story of the collection) provides the seed for the novel Climbers, the novel The Course of the Heart is based on his short story "The Great God Pan", and the story "Isobel Avens returns to Stepney in the Spring" is a short version of the story expanded as the novel Signs of Life.