<Back to Index>

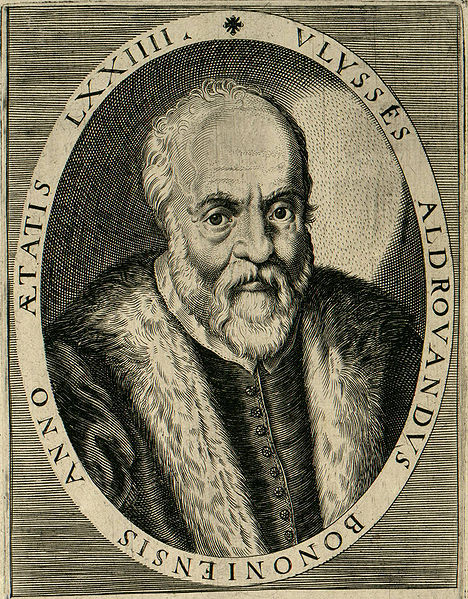

- Naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi, 1522

- Geologist and Meteorologist Jean - André Deluc, 1727

PAGE SPONSOR

Ulisse Aldrovandi (11 September 1522 – 4 May 1605) was an Italian naturalist, the moving force behind Bologna's botanical garden, one of the first in Europe. Carolus Linnaeus and the comte de Buffon reckoned him the father of natural history studies. He is usually referred to, especially in older literature, as Aldrovandus; his name in Italian is equally given as Aldroandi.

Aldrovandi was born in Bologna to a noble family, which sent him to apprentice with merchants, but he found his vocation, after studying humanities and law at the universities of Bologna and Padua and becoming a notary. Successively his interests extended to philosophy and logic which he combined with the study of medicine.

He obtained a degree in medicine and philosophy in 1553 and started teaching logic and philosophy in 1554 at the University of Bologna. In 1559 he became professor of philosophy and in 1561 he became the first professor of natural sciences at Bologna (lectura philosophiae naturalis ordinaria de fossilibus, plantis et animalibus).

In June 1549 he was accused and arrested for heresy, for espousing the anti - trinitarian beliefs of the Anabaptist Camillo Renato. By September he had published an abjuration, but was transferred to Rome, and remained in custody or house arrest till absolved in April 1550. During this time he befriended many local scholars. While in semi - captivity there he became more and more interested in botany, zoology and geology (he is credited for the invention / first written record of this word). From 1551 onward, he organized a variety of expeditions to the Italian mountains, countryside, islands, and coasts in order to collect and catalog plants.

In the course of his life he would assemble one of the most spectacular cabinets of curiosities, his "theater" illuminating natural history comprising some 7000 specimens of the diversità di cose naturali, of which he wrote a description in 1595. Between 1551 and 1554 he organized several expeditions to collect plants for a herbarium, among the first botanizing expeditions. Eventually his herbarium contained about 4760 dried specimens on 4117 sheets in sixteen volumes, preserved at the University of Bologna. He also had various artists, including Jacopo Ligozzi, Giovanni Neri, and Cornelio Schwindt, make illustrations of specimens.

At his demand and under his direction a public botanic garden was created in Bologna in 1568, now the Orto Botanico dell' Università di Bologna. Due to a dispute on the composition of a popular medicine with the pharmacists and doctors of Bologna in 1575 he was suspended from all public position for five years. In 1577 he sought the aid of pope Gregory XIII (a cousin of his mother) who wrote to the authorities of Bologna to reinstate Aldrovandi in his public offices and request financial aid to help him publish his books.

His

vast collections in botany and zoology he willed to the Senate of

Bologna; until 1742 the collections were conserved in the Palazzo

Pubblico, then in the Palazzo Poggi, but were distributed among various

libraries and institutions in the course of the nineteenth century. In

1907 a representative part were reunited at Palazzo Poggi, Bologna,

where the 400th anniversary of his death was memorialized in a

celebrative exhibition in 2005.

Jean - André Deluc or de Luc (8 February 1727 – 7 November 1817) was a Swiss geologist and meteorologist.

He was born at Geneva, descended from a family which had emigrated from Lucca and settled at Geneva in the 15th century. His father, François Deluc, was the author of some publications in refutation of Mandeville and other rationalistic writers, which are best known through Rousseau's humorous account of his ennui in reading them; and he gave his son an excellent education, chiefly in mathematics and natural science. On completing it Jean - André engaged in commerce, which principally occupied the first forty - six years of his life, without any other interruption than that which was occasioned by some journeys of business into the neighboring countries, and a few scientific excursions among the Alps.

During these, however, he collected by degrees, in conjunction with his brother Guillaume Antoine Deluc, a splendid museum of mineralogy and of natural history in general, which was afterwards increased by his nephew J. André Deluc (1763 – 1847), who was also a writer on geology. He at the same time took a prominent part in politics. In 1768 he was sent to Paris on an embassy to the duc de Choiseul, whose friendship he succeeded in gaining. In 1770 he was nominated one of the Council of Two Hundred.

Three years later unexpected reverses in business made it advisable for him to quit his native town, which he only revisited once for a few days. The change was welcome insofar as it set him entirely free for scientific pursuits, and it was with little regret that he removed to England in 1773. He was made a fellow of the Royal Society in the same year, and received the appointment of reader to Queen Charlotte, which he continued to hold for forty - four years, and which afforded him both leisure and a competent income.

In

the latter part of his life he obtained leave to make several tours in

Switzerland, France, Holland and Germany. In Germany he passed the six

years from 1798 to 1804; and after his return he undertook a geological

tour through England. When he was at Göttingen,

in the beginning of his German tour, he received the compliment of

being appointed honorary professor of philosophy and geology in that

university; but he never entered upon the active duties of a

professorship. He was also a correspondent of the French Academy of Sciences, and a member of several other scientific associations. He died at Windsor, Berkshire, England in 1817.

His favorite studies were geology and meteorology, and according to Georges Cuvier, he ranked among the first geologists of his age. His major geological work, Lettres physiques et morales sur les montagnes et sur l'histoire de la terre et de l'homme, first published in 1778, and in a more complete form in 1779, was dedicated to Queen Charlotte. It dealt with the appearance of mountains and the antiquity of the human race, explained the six days of the Mosaic creation as epochs preceding the actual state of the globe, and attributed the deluge to the filling up of cavities supposed to have been left void in the interior of the earth. He published later a series of volumes on geological travels: in northern Europe (1810), in England (1811), and in France, Switzerland and Germany (1813). These were translated into English.

Deluc noticed the disappearance of heat in the thawing of ice about the same time that Joseph Black founded on it his hypothesis of latent heat. He ascertained that water was denser about 40 F. (4 C.) than at the temperature of freezing, expanding equally on each side of the maximum; and he was the originator of the theory, later readvanced by John Dalton, that the quantity of water vapor contained in any space is independent of the presence or density of the air, or of any other elastic fluid.

His Recherches sur les modifications de l'atmosphere (2 vols. 4to, Geneva, 1772; 2nd ed., 4 vols. Paris, 1784) contains experiments on moisture, evaporation and the indications of hygrometers and thermometers, applied to the barometer employed in determining heights. In. the Philosophical Transactions of 1773 appeared his account of a new hygrometer, which resembled a mercurial thermometer, with an ivory bulb, which expanded by moisture, and caused the mercury to descend. The first correct rules published for measuring heights by the barometer were those he gave in the Phil. Trans., 1771, p. 158. His Lettres sur l'histoire physique de la terre (Paris, 1798), addressed to Professor Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, contains an essay on the existence of a General Principle of Morality. It also gives an interesting account of some conversations of the author with Voltaire and Rousseau. Deluc was an ardent admirer of Bacon, on whose writings he published two works; Bacon tel quil est (Berlin, 1800), showing the bad faith of the French translator, who had omitted many passages favorable to revealed religion, and Précis de la philosophie de Bacon (2 vols 8vo, Paris, 1802), giving an interesting view of the progress of natural science. Lettres sur le Christianisme (Berlin and Hanover, 1803) was a controversial correspondence with Dr Teller of Berlin in regard to the Mosaic cosmogony. His Trail elementaire de geologie (Paris, 1809, also in English, by de la Fite, the same year) was principally intended as a refutation of James Hutton and John Playfair. They had shown that geology was driven by the operation of internal heat and erosion. Their system required much more time than Deluc's Mosaic variety of Neptunism allowed.

He sent to the Royal Society, in 1809, a long paper on separating the chemical from the electrical effect of the dry pile a form of Voltaic pile, with a description of the electric column and aerial electroscope, in which he advanced opinions contradicting the latest discoveries of the day, and the council deemed it inexpedient to admit them into the Transactions. The paper was later published in Nicholson's Journal (xxvi.), and the dry column described in it was constructed by various experimental philosophers. His improvements to the dry pile has been regarded as his most important work although he was not in fact its inventor.

Many other papers are in the Transactions and in the Philosophical Magazine. See Philosophical Magazine (November 1817).