<Back to Index>

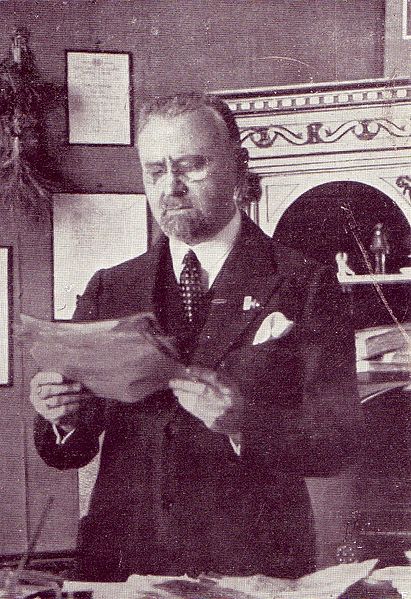

- Founder of the Ceka Giovanni Marinelli, 1879

- Secretary of the National Fascist Party Roberto Farinacci, 1892

- Secretary of the Brescia Fascio Augusto Turati, 1888

PAGE SPONSOR

Giovanni Marinelli (October 18, 1879 — January 11, 1944) was an Italian Fascist political leader.

Marinelli was born in Adria, Veneto.

A wealthy man, he contributed to Fascist success by financing the March on Rome. Secretary of the National Fascist Party (PNF), he created the Ceka, a secret police established on the model of the Soviet Cheka. The Ceka soon established itself as a terrorist squad, and was behind the assassination of Giacomo Matteotti, a prominent member of the opposition to the Fascist régime.

Tried as instigator of the murder, Marinelli was defended by Roberto Farinacci himself, and eventually sentenced to a light punishment. His close friendship with Benito Mussolini ensured that he did not serve the full term. He remained out of the spotlight during most of the next two decades of Fascist rule, and appears to have been involved in the crushing of internal opposition to Mussolini (including moves inside the PNF).

As a member of the Grand Council of Fascism, on July 25, 1943 he joined the coup d'état carried out by Dino Grandi against Mussolini, as an attempt for Italy to switch sides in World War II (out of the alliance with Nazi Germany and into an agreement with the Allies). When the Nazis helped Mussolini re-establish his rule in Northern Italy, as leader of the Italian Social Republic, Marinelli was convicted of treason during the Verona trial of 1944, and executed by firing squad, along with former Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano, Marshal Emilio De Bono, and others.

Roberto Farinacci (October 16, 1892 — April 28, 1945) was a leading Italian Fascist politician, and important member of the National Fascist Party (PNF) before and during World War II, and one of its ardent anti-Semitic proponents.

Born in Isernia, Molise, he was raised in poverty and dropped out of school at a young age, moving to Cremona and beginning working on a railroad there in 1909. Around this time period, he became an irredentist socialist and, when World War I began, a major advocate of Italy’s participation in the war. After the war, Farinacci was an ardent supporter of Benito Mussolini and his Fascist movement. He subsequently established himself as the Ras (local leader, a title borrowed from the Ethiopian aristocracy) of the Fascists in Cremona, publishing the newspaper Cremona Nuova - later on Il Regime Fascista - and organizing Blackshirts combat squads in 1919. The Cremona squads were amongst the most brutal in Italy, and Farinacci effectively used them to terrorize the population into submission to Fascist rule. In 1922, Farinacci appointed himself mayor of Cremona.

Quickly rising as one of the most powerful members of the National Fascist Party, gathering around him a large number of supporters, Farinacci came to represent the most radical syndicalist faction of the party, one that thought Mussolini to be a too liberal leader (likewise, Mussolini believed Farinacci was too violent and irresponsible). Among fascists, Farinacci was known to be particularly anti - clerical, xenophobic, and anti - semitic. Nevertheless, Farinacci’s career continued to rise, and he played a considerable role in establishing Fascist dominance over Italy in 1922, during and after the March on Rome.

In 1925, Farinacci became the second most powerful man in the country when Mussolini appointed him secretary of the Party. He was then used by Mussolini to centralize the PNF. Mussolini used him to purge the party of thousands of its radical members. Mussolini then removed Farinacci and he disappeared from the limelight, and practiced law for much of the late 1920s and early 1930s. In a Time magazine article in 1929, Farinacci was nicknamed the "castor oil man" of Fascism, based on his custom of physically forcing opponents of Fascism to swallow castor oil which he called the "golden nectar of nausea". The effects of swallowing castor oil would cause the victims to suffer severe diarrhea followed by dehydration. The Time article also claims that as secretary of the Fascist party, Farinacci allowed the murderers of Italian Socialist Party deputy Giacomo Matteotti to be let free in 1926. In 1935 Farinacci fought in the Second Italo - Abyssinian War, as a member of the Voluntary Militia for National Security (MVSN) - the new official name of the Blackshirts, and eventually attained the rank of lieutenant general. He lost a hand after fishing with a grenade.

In the same year, he joined the Grand Council of Fascism, thus returning to national prominence. In 1937, Farinacci participated in the Spanish Civil War, and in 1938 became a governmental minister and enforced the anti - semitic racial segregation measures inspired by Nazi Germany.

When World War II began, Farinacci sided with Germany: he frequently communicated with the Nazis, and became one of Mussolini’s advisors on Italy’s dealings with Germany. For his part, Farinacci urged Mussolini to enter Italy into the war as a member of the Axis. In 1941, Farinacci became Inspector of the Militia in Italian occupied Albania.

In July 1943 he took part in the Grand Council of Fascism meeting which led to Mussolini’s downfall. While the majority of the council voted to force Mussolini out of the government, Farinacci did not side against the Duce. After Mussolini's arrest, Farinacci fled to Germany in order to escape arrest.

The Nazi hierarchy considered putting Farinacci in charge of a German backed Italian government in Northern Italy - the Italian Social Republic - but he was passed over in favor of Mussolini when the dictator was rescued by Otto Skorzeny in September (through the raid known as Unternehmen Eiche). Afterwards Farinacci went back to Cremona without taking part in political life. He was executed at Vimercate by Italian partisans in 1945.

Farinacci is cited in David Kertzer's book as being one of the Fascist voices of racial anti - semitism during the Mussolini regime.

He was an atheist.

Augusto Turati (April 16, 1888 — August 27, 1955) was an Italian journalist and Fascist politician.

Born in Parma, after moving to Brescia as a young man, Turati worked on newspapers and became one of the editors at the liberal Provincia di Brescia; he attended law classes, but never graduated. An irredentist and advocate of Italy entering World War I, he volunteered for the front in 1915. In 1918, he returned to Brescia as head editor of the same newspaper.

In 1920, he joined the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento - a year later, the National Fascist Party (Partito Nazionale Fascista, or PNF). Active in trade unionism for the régime backed corporatist enterprises, Turati was a secretary for the Brescia Fascio. In 1926 - 1930, he was secretary of the PNF, helping in the consolidation of Benito Mussolini's rule. He doubled this task with leadership positions in sports: a Federtennis president, a Federazione Italiana di Atletica Leggera one, and leader of the Italian National Olympic Committee (jobs held in 1928 - 1930). In 1930 - 1931, he was a member of the International Olympic Committee. Turati was also the inventor of a short lived and supposedly uniquely Italian team sport which he called volata.

Between 1924 and 1934, Turati served in the Italian Chamber of Deputies; in 1931 - 1932, he was the editor - in - chief of La Stampa. Accused of intrigues against other members of the PNF, Turati was demoted from official positions, and was confined on Rhodes (an Italian possession at the time) in 1933. Redeemed in 1937, he was released and assigned the task of carrying out a massive agricultural experiment in Ethiopia (part of Italian East Africa). He had to return to Italy after the project failed the next year.

Turati moved away from the political scene, and worked as a legal consultant. He was however opposed to Italy's entry into World War II, as well as to the Nazi protected Italian Social Republic; at the end of the war, he nevertheless faced trial, but was acquitted on all charges.

He died in Rome.