<Back to Index>

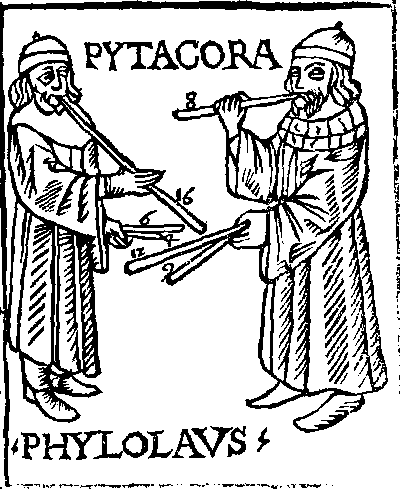

- Philosopher Philolaus of Croton (Φιλόλαος ο Κροτωνιάτης), 470 B.C.

- Philosopher and Astronomer Heraclides Ponticus (Ηρακλείδης ο Ποντικός), 390 B.C.

PAGE SPONSOR

Philolaus (Greek: Φιλόλαος; c. 470 c. 385 BCE) was a Greek Pythagorean and Presocratic philosopher. He argued that all matter is composed of limiting and limitless things, and that the universe is determined by numbers. He is credited with originating the theory that the earth was not the center of the universe.

Philolaus is variously reported as being born in either Croton, Tarentum, or Metapontum. All three places were located in southern Italy. He may have fled the second burning of the Pythagorean meeting place around 454 BCE, after which he migrated to Greece. According to Plato's Phaedo, he was the instructor of Simmias and Cebes at Thebes, around the time the Phaedo takes place, in 399 BCE. This would make him a contemporary of Socrates, and agrees with the statement that Philolaus and Democritus were contemporaries. The various reports about his life are scattered among the writings of much later writers and are of dubious value in reconstructing his life. He apparently lived for some time at Heraclea, where he was the pupil of Aresas, or (as Plutarch calls him) Arcesus. Diogenes Laėrtius is the only authority for the claim that Plato, shortly after the death of Socrates, traveled to Italy where he met with Philolaus and Eurytus. The pupils of Philolaus were said to have included Xenophilus, Phanto, Echecrates, Diocles and Polymnastus. As to his death, Diogenes Laėrtius reports a dubious story that Philolaus was put to death at Croton on account of being suspected of wanting to be the tyrant; a story which Laėrtius even took the trouble to put into verse.

Diogenes Laėrtius speaks of Philolaus composing one book, but elsewhere he speaks of three books, as do Aulus Gellius and Iamblichus. It may have been one treatise, divided into three books. Plato is said to have procured a copy of his book, from which, it was later claimed, Plato composed much of his Timaeus. One of the works of Philolaus was called On Nature, which seems to be the same work which Stobaeus calls On the World, and from which he has preserved a series of passages. Other writers refer to a work entitled Bacchae, which may have been another name for the same work.

Philolaus did away with the ideas of fixed direction in space, and developed one of the first non - geocentric views of the universe. His new way of thinking quite literally revolved around a hypothetical astronomical object he called the Central Fire.

Philolaus says that there is fire in the middle at the center ... and again more fire at the highest point and surrounding everything. By nature the middle is first, and around it dance ten divine bodies - the sky, the planets, then the sun, next the moon, next the earth, next the counterearth, and after all of them the fire of the hearth which holds position at the center. The highest part of the surrounding, where the elements are found in their purity, he calls Olympus; the regions beneath the orbit of Olympus, where are the five planets with the sun and the moon, he calls the world; the part under them, being beneath the moon and around the earth, in which are found generation and change, he calls the sky.Stobaeus

A popular misconception about Philolaus is that he supposed that a sphere of the fixed stars, the five planets, the Sun, Moon and Earth, all moved round his Central Fire, but as these made up only nine revolving bodies, he conceived in accordance with his number theory a tenth, which he called Counter-Earth. This fallacy grows largely out of Aristotle's attempt to lampoon his ideas in his book, Metaphysics. In reality, Philolaus' ideas predated the idea of spheres by hundreds of years. He never recognized the fixed stars as any kind of sphere or object.

His ideas about the nature of the Earth's place in the cosmos was influential. Nicolaus Copernicus mentions in De revolutionibus that Philolaus already knew about the Earth's revolution around a central fire.

Philolaus argued that all matter is composed of limiters and unlimiteds. Limiters set boundaries, such as shape and quantity. Unlimiteds are universal forms and rules such as the four elements of earth, air, fire and water and the continua of space and time. Limiters and unlimiteds are combined together in a harmony (harmonia):

This is the state of affairs about nature and harmony. The essence of things is eternal; it is a unique and divine nature, the knowledge of which does not belong to man. Still it would not be possible that any of the things that are, and are known by us, should arrive to our knowledge, if this essence was not the internal foundation of the principles of which the world was founded, that is, of the limiting and unlimited elements. Now since these principles are not mutually similar, neither of similar nature, it would be impossible that the order of the world should have been formed by them, unless the harmony intervened . . .Philolaus

This

harmony can be described mathematically (similar to the combinations of

elements in modern chemistry). Philolaus used the musical scale to

illustrate his philosophy, whereby whole number ratios limit pleasing

sounds (e.g., the octave, fifth, and fourth are defined by the ratios

2 : 1, 4 : 3 and 3 : 2). Philolaus also regarded the soul

as a "mixture and harmony" of the bodily parts.

Heraclides Ponticus (Greek: Ἡρακλείδης ὁ Ποντικός; c. 390 BC c. 310 BC), also known as Herakleides and Heraklides of Pontus, was a Greek philosopher and astronomer who lived and died at Heraclea Pontica, now Karadeniz Ereğli, Turkey. He is best remembered for proposing that the earth rotates on its axis, from west to east, once every 24 hours. He is also frequently hailed as the originator of the heliocentric theory, although this is doubted.

Heraclides' father was Euthyphron, a wealthy nobleman who sent him to study at the Platonic Academy in Athens under its founder Plato and under his successor Speusippus. According to Suda, Plato, on his departure for Sicily in 361 / 360 BC, left the Academy in the charge of Heraclides. Heraclides was nearly elected successor to Speusippus as head of the academy in 339 / 338 BC, but narrowly lost to Xenocrates.

Like the Pythagoreans Hicetas and Ecphantus, Heraclides proposed that the apparent daily motion of the stars was created by the rotation of the Earth on its axis once a day. This view contradicted the accepted Aristotelian model of the universe, which said that the earth was fixed and that the stars and planets in their respective spheres might also be fixed. Simplicius says that Heraclides proposed that the irregular movements of the planets can be explained if the earth moves while the sun stays still.

Although some historians have proposed that Heraclides taught that Venus and Mercury revolve around the Sun, a detailed investigation of the sources has shown that "nowhere in the ancient literature mentioning Heraclides of Pontus is there a clear reference for his support for any kind of heliocentrical planetary position."

A punning on his name, dubbing him Heraclides "Pompicus," suggests he may have been a rather vain and pompous man and the target of much ridicule. According to Diogenes Laertius, he forged plays under the name of Thespis, and according to the same author, this time drawing from a different source, Dionysius the Deserter composed plays and forged them under the name of Sophocles. Heraclides was deceived by this easily and cited from them as the words of Aeschylus and Sophocles. However, Heraclides seems to have been a versatile and prolific writer on philosophy, mathematics, music, grammar, physics, history and rhetoric, notwithstanding doubts about attribution of many of the works. It appears that he composed various works in dialogue form.

Heraclides also seems to have had an interest in the occult. In particular he focused on explaining trances, visions and prophecies in terms of the retribution of the gods, and reincarnation.

A quote of Heraclides, of particular significance to historians, is his statement that fourth century Rome was a Greek city.