<Back to Index>

- Polymath Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī, 1201

- Astronomer and Mathematician Ibn al-Shatir, 1304

PAGE SPONSOR

Khawaja Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ibn Ḥasan Ṭūsī (Persian: محمد بن محمد بن الحسن طوسی) (born 18 February 1201 in Ṭūs, Khorasan – died on 26 June 1274 in al-Kāżimiyyah district of metropolitan Baghdad), better known as Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (Persian: نصیر الدین طوسی; or simply Tusi in the West), was a Persian polymath and prolific writer: an astronomer, biologist, chemist, mathematician, philosopher, physician, physicist, scientist, theologian and Marja Taqleed. He was of the Ismaili, and subsequently Twelver Shī‘ah Islamic belief. The Muslim scholar Ibn Khaldun (1332 – 1406) considered Tusi to be the greatest of the later Persian scholars.

Nasir al-Din Tusi was born in the city of Tus in medieval Khorasan (now in north - eastern Iran) in the year 1201 and began his studies at an early age. In Hamadan and Tus he studied the Qur'an, Hadith, Shi'a jurisprudence, logic, philosophy, mathematics, medicine and astronomy.

He was apparently born into a Shī‘ah family and lost his father at a young age. Fulfilling the wish of his father, the young Muhammad took learning and scholarship very seriously and traveled far and wide to attend the lectures of renowned scholars and acquire the knowledge which guides people to the happiness of the next world. At a young age he moved to Nishapur to study philosophy under Farid al-Din Damad and mathematics under Muhammad Hasib. He met also Farid al-Din al-'Attar, the legendary Sufi master who was later killed by Mongol invaders and attended the lectures of Qutb al-Din al-Misri.

In Mosul he studied mathematics and astronomy with Kamal al-Din Yunus (d. 639 / 1242). Later on he corresponded with Sadr al-Din al-Qunawi, the son - in - law of Ibn al-'Arabi, and it seems that mysticism, as propagated by Sufi masters of his time, was not appealing to his mind and once the occasion was suitable, he composed his own manual of philosophical Sufism in the form of a small booklet entitled Awsaf al-Ashraf "The Attributes of the Illustrious".

As the armies of Genghis Khan swept his homeland, he fled to join the Ismailis and made his most important contributions in science during this time when he was moving from one stronghold to another. He finally joined Hulagu Khan's ranks, after the invasion of the Alamut castle by the Mongol forces.

During

his stay in Nishapur, Tusi established a reputation as an exceptional

scholar. "Al-Tusi’s prose writing, which number over 150 works,

represent one of the largest collections by a single Islamic author.

Writing in both Arabic and Persian,

Nasir al-Din Tusi dealt with both religious (“Islamic”) topics and non -

religious or secular subjects (“the ancient sciences”). His works include the definitive Arabic versions of the works of Euclid, Archimedes, Ptolemy, Autolycus, and Theodosius of Bithynia.

Tusi convinced Hulegu Khan to construct an observatory for establishing accurate astronomical tables for better astrological predictions. Beginning in 1259, the Rasad Khaneh observatory was constructed in Azarbaijan, west of Maragheh, the capital of the Ilkhanate Empire.

Based on the observations in this for the time being most advanced observatory, Tusi made very accurate tables of planetary movements as depicted in his book Zij-i ilkhani (Ilkhanic Tables). This book contains astronomical tables for calculating the positions of the planets and the names of the stars. His model for the planetary system is believed to be the most advanced of his time, and was used extensively until the development of the heliocentric model in the time of Nicolaus Copernicus. Between Ptolemy and Copernicus, he is considered by many to be one of the most eminent astronomers of his time, and his work and theory in astronomy can also be compared to that of the Chinese scientist Shen Kuo (1031 - 1095 AD).

For his planetary models, he invented a geometrical technique called a Tusi - couple, which generates linear motion from the sum of two circular motions. He used this technique to replace Ptolemy's problematic equant, and it was later employed in Ibn al-Shatir's geocentric model and Nicolaus Copernicus' heliocentric Copernican model. He also calculated the value for the annual precession of the equinoxes and contributed to the construction and usage of some astronomical instruments including the astrolabe.

Ṭūsī criticized Ptolemy's use of observational evidence to show that the Earth was at rest, noting that such proofs were not decisive. Although it does not mean that he was a supporter of mobility of the earth, as he and his 16th century commentator al-Bīrjandī, maintained that the earth's immobility could be demonstrated, but only by physical principles found in natural philosophy. Tusi's criticisms of Ptolemy were similar to the arguments later used by Copernicus in 1543 to defend the Earth's rotation.

About the real essence of the Milky Way, Ṭūsī in his Tadhkira writes:

"The Milky Way, i.e. the galaxy, is made up of a very large number of

small, tightly - clustered stars, which, on account of their concentration

and smallness, seem to be cloudy patches. Because of this, it was

likend to milk in color." Three centuries later the proof of the Milky Way consisting of many stars came in 1610 when Galileo Galilei used a telescope to study the Milky Way and discovered that it is really composed of a huge number of faint stars.

In his Akhlaq - i - Nasri, Al-Tusi put forward a basic theory for the evolution of species. He begins his theory of evolution with the universe once consisting of equal and similar elements. According to Tusi, internal contradictions began appearing, and as a result, some substances began developing faster and differently from other substances. He then explains how the elements evolved into minerals, then plants, then animals, and then humans. Tusi then goes on to explain how hereditary variability was an important factor for biological evolution of living things:

"The organisms that can gain the new features faster are more variable. As a result, they gain advantages over other creatures. [...] The bodies are changing as a result of the internal and external interactions."

Tusi discusses how organisms are able to adapt to their environments:

"Look at the world of animals and birds. They have all that is necessary for defense, protection and daily life, including strengths, courage and appropriate tools [organs] [...] Some of these organs are real weapons, [...] For example, horns - spear, teeth and claws - knife and needle, feet and hoofs - cudgel. The thorns and needles of some animals are similar to arrows. [...] Animals that have no other means of defense (as the gazelle and fox) protect themselves with the help of flight and cunning. [...] Some of them, for example, bees, ants and some bird species, have united in communities in order to protect themselves and help each other."

Tusi recognized three types of living things: plants, animals, and humans. He wrote:

"Animals are higher than plants, because they are able to move consciously, go after food, find and eat useful things. [...] There are many differences between the animal and plant species, [...] First of all, the animal kingdom is more complicated. Besides, reason is the most beneficial feature of animals. Owing to reason, they can learn new things and adopt new, non - inherent abilities. For example, the trained horse or hunting falcon is at a higher point of development in the animal world. The first steps of human perfection begin from here."

Tusi then explains how humans evolved from advanced animals:

"Such humans [probably anthropoid apes] live in the Western Sudan and other distant corners of the world. They are close to animals by their habits, deeds and behavior. [...] The human has features that distinguish him from other creatures, but he has other features that unite him with the animal world, vegetable kingdom or even with the inanimate bodies. [...] Before [the creation of humans], all differences between organisms were of the natural origin. The next step will be associated with spiritual perfection, will, observation and knowledge. [...] All these facts prove that the human being is placed on the middle step of the evolutionary stairway. According to his inherent nature, the human is related to the lower beings, and only with the help of his will can he reach the higher development level."

In chemistry and physics, Tusi stated a version of the law of conservation of mass. He wrote that a body of matter is able to change, but is not able to disappear:

"A body of matter cannot disappear completely. It only changes its form, condition, composition, color and other properties and turns into a different complex or elementary matter."

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi was a supporter of Avicennian logic, and wrote the following commentary on Avicenna's theory of absolute propositions:

"What spurred him to this was that in the assertoric syllogistic Aristotle and others sometimes used contradictories of absolute propositions on the assumption that they are absolute; and that was why so many decided that absolutes did contradict absolutes. When Avicenna had shown this to be wrong, he wanted to give a way of construing those examples from Aristotle."

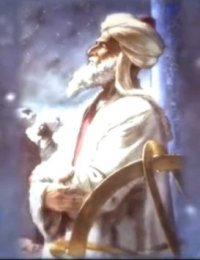

Al-Tusi was the first to write a work on trigonometry independently of astronomy. Al-Tusi, in his Treatise on the Quadrilateral, gave an extensive exposition of spherical trigonometry, distinct from astronomy. It was in the works of Al-Tusi that trigonometry achieved the status of an independent branch of pure mathematics distinct from astronomy, to which it had been linked for so long.

He was the first to list the six distinct cases of a right triangle in spherical trigonometry.

This followed earlier work by Greek mathematicians such as Menelaus of Alexandria, who wrote a book on spherical trigonometry called Sphaerica, and the earlier Muslim mathematicians Abū al-Wafā' al-Būzjānī and Al-Jayyani.

In his On the Sector Figure, appears the famous law of sines for plane triangles.

He also stated the law of sines for spherical triangles, discovered the law of tangents for spherical triangles, and provided proofs for these laws.

In 1265, Tusi wrote a manuscript regarding the calculation for nth roots of an integer. Moreover, he revealed the coefficients of the expansion of a binomial to any power giving the binomial formula and the Pascal triangle relations between binomial coefficients. He also wrote a famous work on theory of color, based on mixtures of black and white, and included sections on jewels and perfumes.

A 60 km diameter lunar crater located on the southern hemisphere of the moon is named after him as "Nasireddin". A minor planet 10269 Tusi discovered by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh in 1979 is named after him. The K.N. Toosi University of Technology in Iran and Observatory of Shamakhy in the Republic of Azerbaijan are also named after him.

Ala Al-Din Abu'l-Hasan Ali Ibn Ibrahim Ibn al-Shatir (1304 – 1375) (Arabic: ابن الشاطر) was an Arab Muslim astronomer, mathematician, engineer and inventor who worked as muwaqqit (موقت, religious timekeeper) at the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, Syria.

His most important astronomical treatise was the Kitab nihayat al-sul fi tashih al-usul (The Final Quest Concerning the Rectification of Principles), in which he drastically reformed the Ptolemaic models of the Sun, Moon, and planets, by his introducing his own non - Ptolemaic models which eliminates the epicycle in the solar model, which eliminate the eccentrics and equant by introducing extra epicycles in the planetary models via the Tusi - couple, and which eliminates all eccentrics, epicycles and equant in the lunar model.

While previous Maragha school models

were just as accurate as the Ptolemaic model, Ibn al-Shatir's

geometrical model was the first that was actually superior to the

Ptolemaic model in terms of its better agreement with empirical observations. Another achievement of Ibn al-Shatir was the rejection of the Ptolemaic model on empirical rather than philosophical grounds. Unlike previous astronomers before him, Ibn al-Shatir was not concerned with adhering to the theoretical principles of cosmology or natural philosophy (or Aristotelian physics), but rather to produce a model that was more consistent with empirical observations. His model was thus in better agreement with empirical observations than

any previous models produced before him. His work thus marked a turning

point in astronomy, which may be considered a "Scientific Revolution

before the Renaissance".

Unlike previous astronomers, Ibn al-Shatir generally had no philosophical objections against Ptolemaic astronomy, but was only concerned with how well it matched his own empirical observations. He employed careful observations of the diameters of the Sun and Moon to test the Ptolemaic models on empirical grounds, testing "the Ptolemaic value for the apparent size of the solar disk by using lunar eclipse observations." His work on his experiments and observations, however, has not survived, but there are references to this work in his The Final Quest Concerning the Rectification of Principles.

As a consequence of his observations,

he formulated his own modification of the Ptolemaic model. Ibn

al-Shatir's concern with the observed solar diameter led him to replace

Ptolemy's epicycle and equant solar

model with a model using three spheres, a large sphere centered on the

Earth which he called the parecliptic, a smaller sphere carried by the

pareclptic, which he called the deferent, and an even smaller sphere

carried by the deferent, which he called the director. The Sun was then

carried by the director.

Although his system was firmly geocentric, he had eliminated the Ptolemaic equant and eccentrics, and the mathematical details of his system were identical to those in Nicolaus Copernicus' De revolutionibus. His lunar model was also no different from the lunar model used by Copernicus. This suggests that Ibn al-Shatir's model may have influenced Copernicus while constructing the heliocentric model. Though it remains uncertain how this may have happened, it is known that Byzantine Greek manuscripts containing the Tusi - couple which Ibn al-Shatir employed had reached Italy in the 15th century. It is also known that Copernicus' diagrams for his heliocentric model, including the markings of points, was nearly identical to the diagrams and markings used by Ibn al-Shatir for his geocentric model, making it very likely that Copernicus may have been aware of Ibn al-Shatir's work.

Y. M. Faruqi writes:

"Ibn al-Shatir’s theory of lunar motion was very similar to that attributed to Copernicus some 150 years later".

"Whereas Ibn al-Shatir’s concept of planetary motion was conceived in order to play an important role in an earth - centered planetary model, Copernicus used the same concept of motion to present his sun - centered planetary model. Thus the development of alternative models took place that permitted an empirical testing of the models."

He devised a timekeeping device incorporating both a universal sundial and a magnetic compass.

The compendium, a multi - purpose astronomical instrument, was first constructed by Ibn al-Shatir. His compendium featured an alhidade and polar sundial among other things. These compendia later became popular in Renaissance Europe.

Ibn al-Shatir described another astronomical instrument which he called the "universal instrument" in his Rays of light on operations with the universal instrument (Al-Ashi'a al-lāmi'a fī 'l-'amal bi-'l-āla al jāmi'a). A commentary on this work entitled Book of Ripe Fruits from Clusters of Universal Instrument (Kitab al-thimār al-yāni'a ‘an qutāf al-āla al-jāmi'a) was later written by the Ottoman astronomer and engineer Taqi al-Din, who employed the instrument at the Istanbul observatory of Taqi al-Din from 1577 - 1580.