<Back to Index>

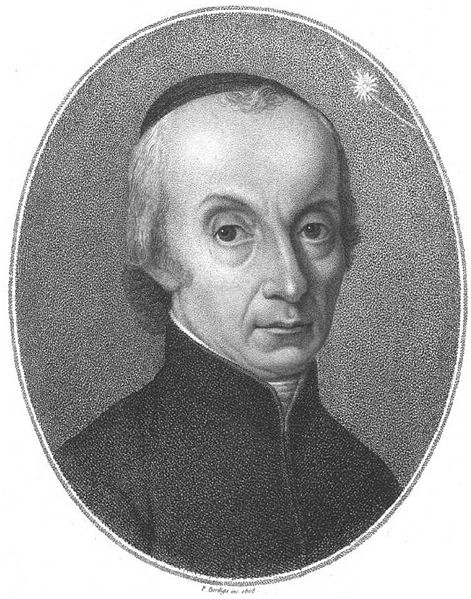

- Mathematician and Astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi, 1746

- Mathematician Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier, 1811

PAGE SPONSOR

Giuseppe Piazzi (July 16, 1746 – July 22, 1826) was an Italian Catholic priest of the Theatine order, mathematician, and astronomer. He was born in Ponte in Valtellina, and died in Naples. He established an observatory at Palermo, now the Osservatorio Astronomico di Palermo – Giuseppe S. Vaiana.

No documented account of Piazzi's scientific education is available in any of the biographies of the astronomer, even in the oldest ones. Piazzi certainly did some studies in Turin, quite likely attending Giovan Battista Beccaria's lessons. In the years 1768 - 1770 he was resident at the Theatines' Home in S. Andrea della Valle, Rome, while studying Mathematics under Jd.

In July 1770 he took the chair of Mathematics at the University of Malta. In December 1773 he moved to Ravenna as "prefetto degli studenti" and lecturer in Philosophy and Mathematics at the Collegio dei Nobili, where he stayed until the beginning of 1779. After a short period spent in Cremona and in Rome, in March 1781 Piazzi moved to Palermo as lecturer in Mathematics at the University of Palermo (at the time known as "Accademia de' Regj Studi").

He kept this position until 19 January 1787, when he became Professor of Astronomy. Almost at the same time he was granted permission to spend two years in Paris and London in order to undergo some practical training in astronomy and also to get some instruments to be specially built for the Palermo Observatory, whose foundation he was in charge of.

In the period spent abroad, from 13 March 1787 until the end of 1789, Piazzi became acquainted with the major French and English astronomers of his time and was able to have the famous altazimuthal circle made by Jesse Ramsden, one of the most skilled instrument makers of the 18th century. The circle was the most important instrument of the Palermo Observatory, whose official foundation took place on 1 July 1790.

In 1817 King Ferdinand put

Piazzi in charge of the completion of the Capodimonte (Naples)

Observatory, naming him General Director of the Naples and Sicily

Observatories.

He supervised the compilation of the Palermo Catalogue of stars, containing 7,646 star entries with unprecedented precision, including the star names "Garnet Star" from Herschel, and the original Rotanev and Sualocin. The work on this catalog was started in 1789, enabling Piazzi and collaborators to observe the sky methodically. The catalog was not finished for first edition publication until 1803.

Spurred

by the success discovering Ceres, and in the line of his

catalog program, Piazzi studied the proper motions of stars in order

to find parallax measurement candidates. One of them, 61 Cygni, was specially appointed as a good candidate for measuring a parallax, which was later performed by Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel. The star system 61 Cygni is sometimes still called variously Piazzi's Flying Star and Bessel's Star.

Piazzi discovered Ceres, today known as the largest member of the asteroid belt. On January 1, 1801, Piazzi discovered a "stellar object" that moved against the background of stars. At first he thought it was a fixed star, but once he noticed that it moved, he became convinced it was a planet, or as he called it, "a new star".

In his journal, he wrote: "The light was a little faint, and of the color of Jupiter, but similar to many others which generally are reckoned of the eighth magnitude. Therefore I had no doubt of its being any other than a fixed star. In the evening of the second I repeated my observations, and having found that it did not correspond either in time or in distance from the zenith with the former observation, I began to entertain some doubts of its accuracy. I conceived afterwards a great suspicion that it might be a new star. The evening of the third, my suspicion was converted into certainty, being assured it was not a fixed star. Nevertheless before I made it known, I waited till the evening of the fourth, when I had the satisfaction to see it had moved at the same rate as on the preceding days."

In spite of his assumption that it was a planet, he took the conservative route and announced it as a comet. In a letter to astronomer Barnaba Oriani of Milan he made his suspicions known in writing:

- "I have announced this star as a comet, but since it is not accompanied by any nebulosity and, further, since its movement is so slow and rather uniform, it has occurred to me several times that it might be something better than a comet. But I have been careful not to advance this supposition to the public."

He was not able to observe it long enough as it was soon lost in the glare of the Sun. Unable to compute its orbit with existing methods, the renowned mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss developed a new method of orbit calculation that allowed astronomers to locate it again. After its orbit was better determined, it was clear that Piazzi's assumption was correct and this object was not a comet but more like a small planet. Coincidentally, it was also almost exactly where the Titius - Bode law predicted a planet would be.

Piazzi named it "Ceres Ferdinandea," after the Roman and Sicilian goddess of grain and King Ferdinand IV of Naples and Sicily. The Ferdinandea part was later dropped for political reasons. Ceres turned out to be the first, and largest, of the asteroids existing within the asteroid belt. Ceres is today called a dwarf planet.

In 1871, a memorial statue of Piazzi sculpted by Costantino Corti was dedicated in the main plaza of his birthplace, Ponte. In 1923, the 1000th asteroid to be numbered was named 1000 Piazzia in his honor. The lunar crater Piazzi was named after him in 1935. More recently, a large albedo feature, probably a crater, imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope on Ceres, has been informally named Piazzi.

Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier (11 March 1811 – 23 September 1877) was a French mathematician who specialized in celestial mechanics and is best known for his part in the discovery of Neptune.

Le Verrier was born at Saint-Lô, Manche, France, and studied at Ecole Polytechnique. Following a brief period studying chemistry under Gay - Lussac, he switched to astronomy, particularly celestial mechanics, and accepted a job at the Paris Observatory, where he spent most of his professional life, and eventually became that institution's Director.

In 1846, Le Verrier became a member of the French Academy of Sciences, and in 1855, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Le Verrier's name is one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

Le Verrier's most famous achievement is his prediction of the existence of the then unknown planet Neptune, using only mathematics and astronomical observations of the known planet Uranus. Encouraged by physicist Arago, Director of the Paris Observatory, Le Verrier was intensely engaged for months in complex calculations to explain small but systematic discrepancies between Uranus's observed orbit and the one predicted from the laws of gravity of Newton. At the same time, but unknown to Le Verrier, similar calculations were made by John Couch Adams in England. Le Verrier announced his final predicted position for Uranus's unseen perturbing planet publicly to the French Academy on 31 August 1846, two days before Adams's final solution, which turned out to be 12° off the mark, was privately mailed to the Royal Greenwich Observatory. Le Verrier transmitted his own prediction by 18 September letter to Johann Galle of the Berlin Observatory. The letter arrived five days later, and the planet was found with the Berlin Fraunhofer refractor that same evening, 23 September 1846, by Galle and Heinrich d'Arrest within 1° of the predicted location near the boundary between Capricorn and Aquarius.

There was, and to an extent still is, controversy over the apportionment of credit for the discovery. There is no ambiguity to the discovery claims of Le Verrier, Galle, and d'Arrest. Adams's work was begun earlier than Le Verrier's but was finished later and was unrelated to the actual discovery. Not even the briefest account of Adams's predicted orbital elements was published until more than a month after Berlin's visual confirmation. But Adams himself made full public acknowledgement of Le Verrier's priority and credit (not forgetting to mention the role of Galle) when he gave his paper to the Royal Astronomical Society in November 1846:

I mention these dates merely to show that my results were arrived at independently, and previously to the publication of those of M. Le Verrier, and not with the intention of interfering with his just claims to the honours of the discovery; for there is no doubt that his researches were first published to the world, and led to the actual discovery of the planet by Dr. Galle, so that the facts stated above cannot detract, in the slightest degree, from the credit due to M. Le Verrier.

In 1859, Le Verrier was the first to report that the slow precession of Mercury’s orbit around the Sun could not be completely explained by Newtonian mechanics and perturbations by the known planets. He suggested, among possible explanations, that another planet (or perhaps, instead, a series of smaller 'corpuscules') might exist in an orbit even closer to the Sun than that of Mercury, to account for this perturbation. (Other explanations considered included a slight oblateness of the Sun.) The success of the search for Neptune based on its perturbations of the orbit of Uranus led astronomers to place some faith in this possible explanation, and the hypothetical planet was even named Vulcan. However, no such planet was ever found, and the anomalous precession was eventually explained by general relativity theory.

Le Verrier had a wife and children. He died in Paris, France and was buried in the Cimetière Montparnasse. A large stone celestial globe sits over his grave. He will be remembered by the phrase attributed to Arago: "the man who discovered a planet with the point of his pen."