<Back to Index>

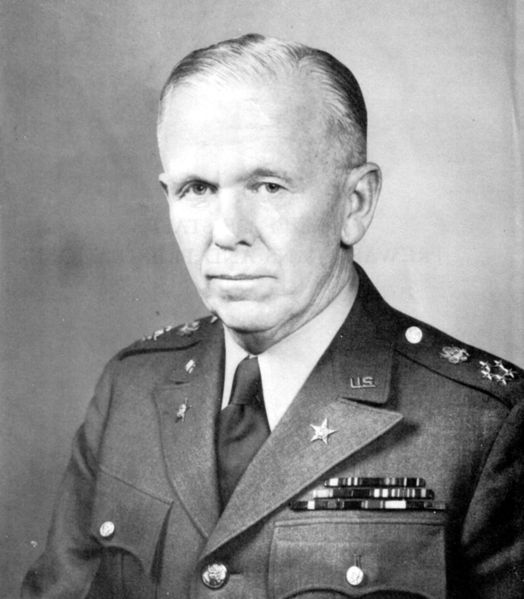

- United States Army Chief of Staff General of the Army George Catlett Marshall, 1880

- Commander in Chief, United States Fleet and Chief of Naval Operations Fleet Admiral Ernest Joseph King, 1878

PAGE SPONSOR

George Catlett Marshall (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American military leader, Chief of Staff of the Army, Secretary of State, and the third Secretary of Defense. Once noted as the "organizer of victory" by Winston Churchill for his leadership of the Allied victory in World War II, Marshall served as the United States Army Chief of Staff during the war and as the chief military adviser to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. As Secretary of State, his name was given to the Marshall Plan, for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953.

George Catlett Marshall was born into a middle class family in Uniontown, Pennsylvania, the son of George Catlett Marshall, Sr. and Laura Emily (Bradford) Marshall. Marshall was a scion of an old Virginia family, as well as a distant relative of former Chief Justice John Marshall. Marshall graduated from the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), where he was initiated into the Kappa Alpha Order, in 1901.

Following graduation from VMI, Marshall was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the U.S. Army. Until World War I, he was posted to various positions in the US and the Philippines and was trained in modern warfare. His pre-war service included a tour at Fort Leavenworth, KS, from 1906 to 1910 as both a student and an instructor. During the war, he had roles as a planner of both training and operations. He went to France in mid 1917 as the director of training and planning for the 1st Infantry Division. In mid 1918, he was promoted to American Expeditionary Forces headquarters, where he worked closely with his mentor General John J. Pershing and was a key planner of American operations. He was instrumental in the design and coordination of the Meuse - Argonne offensive, which contributed to the defeat of the German Army on the Western Front.

In 1919, he became an aide - de - camp to General John J. Pershing. Between 1920 and 1924, while Pershing was Army Chief of Staff, Marshall worked in a number of positions in the US Army, focusing on training and teaching modern, mechanized warfare. Between World Wars I and II, he was a key planner and writer in the War Department, commanded the 15th Infantry Regiment (United States) for three years in China, and taught at the Army War College. From June 1932 to June 1933 he was the Commanding Officer at Fort Screven, Savannah Beach, Georgia, now named Tybee Island. In 1934, Col. Marshall put Edwin F. Harding in charge of the Infantry School's publications, and Harding became editor of Infantry in Battle, a book that codified the lessons of World War I. Infantry in Battle is still used as an officer's training manual in the Infantry Officer's Course and was the training manual for most of the infantry officers and leaders of World War II.

Marshall was promoted to Brigadier General in October 1936. He commanded the Vancouver Barracks in Vancouver, Washington, from 1936 – 1938. Nominated by President Franklin Roosevelt to be Army Chief of Staff, Marshall was promoted to General and sworn in on September 1, 1939, the day German forces invaded Poland, which began World War II. He would hold this post until the end of the war in 1945.

As Chief of Staff, Marshall organized the largest military expansion in U.S. history, inheriting an outmoded, poorly equipped army of 189,000 men and, partly drawing from his experience teaching and developing techniques of modern warfare as an instructor at the Army War College, coordinated the large scale expansion and modernization of the U.S. Army. Though he had never actually led troops in combat, Marshall was a skilled organizer with a talent for inspiring other officers. Many of the American generals who were given top commands during the war were either picked or recommended by Marshall, including Dwight Eisenhower, Lloyd Fredendall, Leslie McNair, Mark Wayne Clark and Omar Bradley.

Faced

with the necessity of turning an army of former civilians into a force

of over eight million soldiers by 1942 (a fortyfold increase within

three years), Marshall directed General Leslie McNair to focus efforts

on rapidly producing large numbers of soldiers. With the exception of

airborne forces, Marshall approved McNair's concept of an abbreviated

training schedule for men entering Army land forces training,

particularly in regard to basic infantry skills, weapons proficiency,

and combat tactics. At

the time, most U.S. commanders at lower levels had little or no combat

experience of any kind; without the input of experienced British or

Allied combat officers on the nature of modern warfare and enemy

tactics, many of them resorted to formulaic training methods emphasizing

static defense and orderly large scale advances by motorized convoys

over improved roads. In

consequence, Army forces deploying to Africa suffered serious initial

reverses when encountering German armored combat units in Africa at Kasserine Pass and other major battles. Even

as late as 1944, U.S. soldiers undergoing stateside training in

preparation for deployment against German forces in Europe were not

being trained in combat procedures and tactics currently being employed

there.

Originally, Marshall had planned a 200 division Army with a system of unit rotation such as practiced by the British and other Allies. By mid 1943, however, after pressure from government and business leaders to preserve manpower for industry and agriculture, he had abandoned this plan in favor of a 90 division Army using individual replacements sent via a circuitous process from training to divisions in combat. The individual replacement system (IRS) devised by Marshall and implemented by McNair greatly exacerbated problems with unit cohesion and effective transfer of combat experience to newly trained soldiers and officers. In Europe, where there were few pauses in combat with German forces, the individual replacement system had broken down completely by late 1944. Hastily trained replacements or service personnel re-assigned as infantry were given six weeks' refresher training and thrown into battle with Army divisions locked in front line combat. The new men were often not even proficient in the use of their own rifles or weapons systems, and once in combat, could not receive enough practical instruction from veterans before being killed or wounded, usually within the first three or four days. Under such conditions, many replacements suffered a crippling loss of morale, while veteran soldiers were kept in line units until they were killed, wounded, or incapacitated by battle fatigue or physical illness. Incidents of soldiers AWOL from combat duty as well as battle fatigue and self inflicted injury rose rapidly during the last eight months of the war with Germany. As one historian later concluded, "Had the Germans been given a free hand to devise a replacement system..., one that would do the Americans the most harm and the least good, they could not have done a better job."

Marshall's

abilities to pick competent field commanders during the early part of

the war was decidedly mixed. While he had been instrumental in advancing

the career of the able Dwight D. Eisenhower, he had also recommended

the swaggering Lloyd Fredendall to Eisenhower for a major command in the American invasion of North Africa during Operation Torch.

Marshall was especially fond of Fredendall, describing him as "one of

the best" and remarking in a staff meeting when his name was mentioned,

"I like that man; you can see determination all over his face."

Eisenhower duly picked him to command the 39,000 man Central Task Force

(the largest of three) in Operation Torch. Both men would later come to regret that decision after the U.S. Army debacle at Kasserine Pass.

During World War II, Marshall was instrumental in preparing the U.S. Army and Army Air Forces for the invasion of the European continent. Marshall wrote the document that would become the central strategy for all Allied operations in Europe. He initially scheduled Operation Overlord for April 1, 1943, but met with strong opposition from Winston Churchill, who convinced Roosevelt to commit troops to Operation Husky for the invasion of Italy. Some authors think that World War II could have been terminated one year earlier if Marshall had had his way, others think that such invasion would have meant utter failure. But it is true that the German Army in 1943 was overstretched, and defense works in Normandy were not ready.

It was assumed that Marshall would become the Supreme Commander of Operation Overlord, but Roosevelt selected Dwight Eisenhower as Supreme Commander. While Marshall enjoyed considerable success in working with Congress and President Franklin D. Roosevelt, he refused to lobby for the position. President Roosevelt did not want to lose his presence in the states. He told Marshall, "I didn't feel I could sleep at ease if you were out of Washington." When rumors circulated that the top job would go to Marshall, many critics viewed the transfer as a demotion for Marshall, since he would leave his position as Chief of Staff of the Army and lose his seat on the Combined Chiefs of Staff.

On December 16, 1944, Marshall became the first American general to be promoted to five - star rank, the newly created General of the Army. He was the second American to be promoted to a five - star rank, as William Leahy was promoted to fleet admiral the previous day. This position is the American equivalent rank to field marshal.

Throughout the remainder of World War II, Marshall coordinated Allied operations in Europe and the Pacific. He was characterized as the organizer of Allied victory by Winston Churchill. Time Magazine named Marshall Man of the Year for 1943. Marshall resigned his post of Chief of Staff in 1945, but did not retire, as regulations stipulate that Generals of the Army remain on active duty for life.

After

World War II ended, the Congressional Joint Committee on the

Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack received testimony on the

intelligence failure. It amassed 25,000 pages of documents, 40 volumes,

and included nine reports and investigations, eight of which had been

previously completed. Among these documents was a report critical of

Marshall for his delay in sending General Walter Short,

the Army commander in Hawaii, important information concerning a

possible attack on December 6 and 7. The report also criticized

Marshall’s admitted lack of knowledge of the readiness of the Hawaiian

Command during November and December 1941. Ten days after the attack,

Lt. General Short and Admiral Husband E. Kimmel,

commander of the Navy at Pearl Harbor, were both relieved of their

duties. The final report of the Joint Committee did not single out and

fault Marshall. While the report was critical of the overall situation,

the committee noted that subordinates had failed to pass on important

information to their superiors, including Marshall. The report noted

that once General Marshall received information about the impending

attack, he immediately passed it on.

In December 1945, President Harry Truman sent Marshall to China to broker a coalition government between the Nationalist allies under Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and Communists under Mao Zedong. Marshall had no leverage over the Communists, but he threatened to withdraw American aid essential to the Nationalists. Both sides rejected his proposals and the Chinese Civil War escalated, with the Communists winning in 1949. His mission a failure, he returned to the United States in January 1947. As Secretary of State in 1947 – 48, Marshall seems to have disagreed with strong opinions in The Pentagon and State department that Chiang's success was vital to American interests, insisting that U.S. troops not become involved.

After Marshall's return to the U.S. in early 1947, Truman appointed Marshall Secretary of State. He became the spokesman for the State Department's ambitious plans to rebuild Europe. On June 5, 1947 in a speech at Harvard University, he outlined the American plan. The European Recovery Program, as it was formally known, became known as the Marshall Plan. Clark Clifford had

suggested to Truman that the plan be called the Truman Plan, but Truman

immediately dismissed that idea and insisted that it be called the

Marshall Plan. The Marshall Plan would help Europe quickly rebuild and modernize its economy along American lines. The Soviet Union forbade its satellites to participate.

Marshall was again named Time's Man of the Year for 1947 and received the Nobel Peace Prize for his post war work in 1953. He was the only U.S. Army General to have received this honor.

As Secretary of State, Marshall strongly opposed recognizing the state of Israel. Marshall felt that if the state of Israel was declared that a war would break out in the Middle East (which it did in 1948 one day after Israel declared independence). Marshall saw recognizing the Jewish state as a political move to gain Jewish support in the upcoming election, in which Truman was expected to lose to Dewey. He told President Truman in May 1948, "If you (recognize the state of Israel) and if I were to vote in the election, I would vote against you."

Marshall resigned from the State Department because of ill health on January 7, 1949, and the same month became chairman of American Battle Monuments Commission. In September 1949, Marshall was named president of the American National Red Cross.

When the early months of the Korean War showed how poorly prepared the Defense Department was, Truman fired Secretary Louis A. Johnson and named Marshall as Secretary of Defense in

September 1950. On September 30, Defense Secretary George Marshall sent

an eyes - only message to MacArthur instructing MacArthur to escalate the

war in Korea "We want you to feel unhampered tactically and

strategically to proceed north of the 38th parallel." His

main role was to restore confidence and rebuild the armed forces from

the post war state of demobilization. He served in that post for one

year, retiring from public office for good in September 1951. In 1953,

he represented America at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom.

U.S. Senator Joe McCarthy, whose hearings and black lists later spawned the term McCarthyism, gave a speech titled America's Retreat from Victory: The Story of George Catlett Marshall (1951), in which he argued that General Albert Coady Wedemeyer had prepared a wise plan that would keep China a valued ally, but that it had been sabotaged. He concluded that "If Marshall were merely stupid, the laws of probability would dictate that part of his decisions would serve this country's interest." He suggested that Marshall was old and feeble and easily duped but did not charge Marshall with treason. McCarthy specifically alleged:

"When Marshall was sent to China with secret State Department orders, the Communists at that time were bottled up in two areas and were fighting a losing battle, but that because of those orders the situation was radically changed in favor of the Communists. Under those orders, as we know, Marshall embargoed all arms and ammunition to our allies in China. He forced the opening of the Nationalist - held Kalgan Mountain pass into Manchuria, to the end that the Chinese Communists gained access to the mountains of captured Japanese equipment. No need to tell the country about how Marshall tried to force Chiang Kai-shek to form a partnership government with the Communists."

Marshall died on Friday, October 16, 1959. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

After leaving office, in a television interview, Harry Truman was asked who he thought was the American who made the greatest contribution of the last thirty years. Without hesitation, Truman picked Marshall, adding "I don't think in this age in which I have lived, that there has been a man who has been a greater administrator; a man with a knowledge of military affairs equal to General Marshall."

Orson Welles, in an interview with Dick Cavett, called Marshall "...the greatest human being who was also a great man... He was a tremendous gentlemen, an old fashioned institution which isn't with us anymore."

In spite of world wide acclaim, dozens of national and international awards and honors and the Nobel Peace prize, public opinion became bitterly divided along party lines on Marshall's record. While campaigning for president in 1952, Eisenhower denounced the Truman administration's failures in Korea, campaigned alongside McCarthy, and refused to defend Marshall's policies. Marshall, who assisted Eisenhower in his promotions, and in refusing to lobby for the position of supreme commander effectively stood aside, thus allowing Eisenhower an opportunity to be chosen for that role, was surprised at the lack of a positive statement supporting him from Eisenhower during the McCarthy hearings.

He married Elizabeth Carter Cole of San Antonio, Texas,

in 1902. She died in 1927. In 1930, he married Katherine Boyce Tupper

(formerly Mrs. Clifton Stevenson Brown), a widowed mother of three

children. One of Marshall's stepsons with Tupper, Army Lt. Allen Tupper

Brown, was killed by a German sniper in Italy on May 29, 1944. George

Marshall maintained a home, known as Dodona Manor (now restored), in Leesburg, Virginia. Actress Kitty Winn is his step - granddaughter.

Fleet Admiral Ernest Joseph King (23 November 1878 – 25 June 1956) was Commander in Chief, United States Fleet and Chief of Naval Operations (COMINCH-CNO) during World War II. As COMINCH, he directed the United States Navy's operations, planning, and administration and was a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He was the U.S. Navy's second most senior officer after Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy, and the second admiral to be promoted to five star rank. As COMINCH, he served under Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox and later under James Forrestal.

King was born in Lorain, Ohio, on 23 November 1878, the son of James Clydesdale King and Elizabath Keam King. He attended the United States Naval Academy from 1897 until 1901, graduating fourth in his class. During his senior year at the Academy, he attained the rank of Midshipman Lieutenant Commander, the highest midshipman ranking at that time.

While still at the Academy, he served on the USS San Francisco during the Spanish American War. After graduation, he served as a junior officer on the survey ship USS Eagle, the battleships USS Illinois, USS Alabama and USS New Hampshire, and the cruiser USS Cincinnati.

While still at the Naval Academy, he met Martha Rankin ("Mattie") Egerton, a Baltimore socialite, whom he married in a ceremony at the Naval Academy Chapel on 10 October 1905. They had six daughters, Claire, Elizabeth, Florence, Martha, Eleanor and Mildred; and then a son, Ernest Joseph King, Jr. (Commander, USN.).

King returned to shore duty at Annapolis in 1912. He received his first command, the destroyer USS Terry in 1914, participating in the United States occupation of Veracruz. He then moved on to a more modern ship, USS Cassin.

During World War I he served on the staff of Vice Admiral Henry T. Mayo, the Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet. As such, he was a frequent visitor to the Royal Navy and occasionally saw action as an observer on board British ships. It appears that his Anglophobia developed during this period, although the reasons are unclear. He was awarded the Navy Cross "for distinguished service in the line of his profession as assistant chief of staff of the Atlantic Fleet".

After the war, King, now a captain, became head of the Naval Postgraduate School. Along with Captains Dudley Wright Knox and William S. Pye, King prepared a report on naval training that recommended changes to

naval training and career paths. Most of the report's recommendations were accepted and became policy.

Before World War I he served in the surface fleet. From 1923 to 1925, he held several posts associated with submarines. As a junior captain, the best sea command he was able to secure in 1921 was the store ship USS Bridge. The relatively new submarine force offered the prospect of advancement.

King attended a short training course at the Naval Submarine Base New London before taking command of a submarine division, flying his commodore's pennant from USS S-20. He never earned his Submarine Warfare insignia, although he did propose and design the now familiar dolphin insignia. In 1923, he took over command of Submarine Base itself. During this period, he directed the salvage of the submarine USS S-51, earning the first of his three Distinguished Service Medals.

In 1926, Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, asked King if he would consider a transfer to naval aviation. King accepted the offer and took command of the aircraft tender USS Wright with additional duties as Senior Aide on the Staff of Commander Air Squadrons, Atlantic Fleet.

That year, the United States Congress passed a law (10 USC Sec. 5942) requiring commanders of all aircraft carriers, seaplane tenders, and aviation shore establishments be qualified naval aviators. King therefore reported to Naval Air Station Pensacola for aviator training in January 1927. He was the only captain in his class of twenty, which also included Commander Richmond K. Turner. King received his wings as Naval Aviator No. 3368 on 26 May 1927 and resumed command of Wright. For a time, he frequently flew solo, flying down to Annapolis for weekend visits to his family, but his solo flying was cut short by a naval regulation prohibiting solo flights for aviators aged 50 or over. However, the History Chair at the Naval Academy from 1971 - 1976 disputes this assertion, stating that after King soloed, he never flew alone again. His biographer described his flying ability as "erratic" and quoted the commander of the squadron with which he flew as asking him if he "knew enough to be scared?" Between 1926 and 1936 he flew an average of 150 hours annually.

King commanded Wright until 1929, except for a brief interlude overseeing the salvage of USS S-4.

He then became Assistant Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics under

Moffett. The two fell out over certain elements of Bureau policy, and he

was replaced by Commander John Henry Towers and transferred to command of Naval Station Norfolk.

On 20 June 1930, King became captain of the carrier USS Lexington – then one of the largest aircraft carriers in the world – which he commanded for the next two years. During his tenure aboard the Lexington, Captain King was the commanding officer of notable science fiction author Robert A. Heinlein, then Ensign Heinlein, prior to his medical retirement from the US Navy. During that time, Ensign Heinlein dated one of King's daughters.

In 1932 he attended the Naval War College. In a war college thesis entitled "The Influence of National Policy on Strategy", King expounded on the theory that America's weakness was Representative democracy:

| “ | Historically... it is traditional and habitual for us to be inadequately prepared. Thus is the combined result of a number factors, the character of which is only indicated: democracy, which tends to make everyone believe that he knows it all; the preponderance (inherent in democracy) of people whose real interest is in their own welfare as individuals; the glorification of our own victories in war and the corresponding ignorance of our defeats (and disgraces) and of their basic causes; the inability of the average individual (the man in the street) to understand the cause and effect not only in foreign but domestic affairs, as well as his lack of interest in such matters. Added to these elements is the manner in which our representative (republican) form of government has developed as to put a premium on mediocrity and to emphasise the defects of the electorate already mentioned. | ” |

Following the death of Admiral Moffet in the crash of the airship USS Akron on 4 April 1933, King became Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, and was promoted to Rear Admiral on 26 April 1933. As Bureau chief, King worked closely with the chief of the Bureau of Navigation, Rear Admiral William D. Leahy, to increase the number of naval aviators.

At the conclusion of his term as Bureau Chief in 1936, King became Commander, Aircraft, Base Force, at Naval Air Station North Island. He was promoted to Vice Admiral on 29 January 1938 on becoming Commander, Aircraft, Battle Force – at the time one of only three vice admiral billets in the US Navy.

King hoped to be appointed as either CNO or Commander - in - Chief of the U.S. Fleet, but on 15 June 1939, he was posted to the General Board, an elephant's graveyard where senior officers sat out the time remaining before retirement. A series of extraordinary events would alter this outcome.

His career was resurrected by one of his few friends in the Navy, CNO Admiral Harold "Betty" Stark, who realized that King's talent for command was being wasted on the General Board. Stark appointed King as Commander - in - Chief, Atlantic Fleet, in the fall of 1940, and he was promoted to Admiral in February 1941. On 30 December 1941 he became Commander - in - Chief, United States Fleet. On 18 March 1942, he was appointed Chief of Naval Operations, relieving Admiral Stark. He is the only person to hold this combined command. After turning 64 on 23 November 1944, he wrote a message to President Roosevelt to say he had reached mandatory retirement age. Roosevelt replied with a note reading "So what, old top?". On 17 December 1944 he was promoted to the newly created rank of Fleet Admiral. He left active duty on 15 December 1945 but was recalled as an advisor to the Secretary of the Navy in 1950.

After retiring, King lived in Washington, D.C..

He was active in his early post retirement, but suffered a debilitating

stroke in 1947, and subsequent ill health ultimately forced him to stay

in Naval Hospitals at Bethesda, Maryland, and at the Portsmouth Naval

Shipyard in Kittery, Maine. He died of a heart attack in Kittery on 26

June 1956 and was buried in the United States Naval Academy Cemetery at Annapolis, Maryland.

King was highly intelligent and extremely capable, but controversial. Some consider him to have been one of the greatest admirals of the 20th century; others, however, point out that he never commanded ships or fleets at sea in war time, and that his Anglophobia led him to make decisions which cost many Allied lives. Others see as indicative of strong leadership his willingness and ability to counter both British and U.S. Army influence on American World War II strategy, and praise his sometimes outspoken recognition of the strategic importance of the Pacific War. His instrumental role in the decisive Guadalcanal Campaign has earned him admirers in the United States and Australia, and some also consider him an organizational genius. He was considered rude and abrasive; as a result, King was loathed by many officers with whom he served.

He was... perhaps the most disliked Allied leader of World War II. Only British Field Marshal Montgomery may have had more enemies... King also loved parties and often drank to excess. Apparently, he reserved his charm for the wives of fellow naval officers. On the job, he "seemed always to be angry or annoyed."

There was a tongue - in - cheek remark about King, made by one of his daughters, carried about by Naval personnel at the time that "he is the most even - tempered person in the United States Navy. He is always in a rage." Roosevelt once described King as a man who "shaves every morning with a blow torch".

It

is commonly reported that when King was called to be CominCh he

remarked,"When they get in trouble they send for the sons - of - bitches”.

However, when he was later asked if he had said this King replied that

he had not but would have if he had thought of it.

At the start of US involvement in World War II, blackouts on the U.S. eastern seaboard were not in effect, and commercial ships were not traveling under convoy. King's critics attribute the delay to implement these measures to his Anglophobia, as the convoys and seaboard blackouts were British proposals, and King was supposedly loath to have his much beloved U.S. Navy adopt any ideas from the Royal Navy. He also refused, until March 1942, the loan of British convoy escorts when the USN had only a handful of suitable vessels. He was, however, aggressive in driving his destroyer captains to attack U-boats in defense of convoys and in planning counter measures against German surface raiders, even before the formal declaration of war by Germany.

Instead of convoys, King had the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard perform regular anti - submarine patrols, but these patrols followed a regular schedule. U-boat commanders learned the schedule, and coordinated their attacks to these schedules. Leaving the lights on in coastal towns back - lit merchant ships to the U-Boats. As a result, there were disastrous shipping losses — two million tons lost in January and February 1942 alone, and urgent pressure applied from both sides of the Atlantic. However, King resisted the use of convoys because he was convinced that the Navy lacked sufficient escort vessels to make them effective. The formation of convoys with inadequate escort would also result in increased port - to - port time, giving the enemy concentrated groups of targets rather than single ships proceeding independently. Furthermore, blackouts were a politically sensitive issue – coastal cities resisted, citing the loss of tourism revenue.

It was not until May 1942 that King marshaled resources — small cutters and private vessels that he had previously scorned — to establish a day - and - night interlocking convoy system running from Newport, Rhode Island, to Key West, Florida.

By August 1942, the submarine threat to shipping in U.S. coastal waters had been contained. The U-boats' "second happy time" ended, with the loss of seven U-boats and a dramatic reduction in shipping losses. The same effect occurred when convoys were extended to the Caribbean. Despite the ultimate defeat of the U-boat, some of King's initial decisions in this theater could be viewed as flawed.

In King's defense, noted naval historian Professor Robert W. Love has stated that "Operation Drumbeat (or Paukenschlag)

off the Atlantic Coast in early 1942 succeeded largely because the U.S.

Navy was already committed to other tasks: transatlantic

escort - of - convoy operations, defending troop transports, and maintaining

powerful, forward deployed Atlantic Fleet striking forces to prevent a

breakout of heavy German surface forces. Navy leaders, especially

Admiral King, were unwilling to risk troop shipping to provide escorts

for coastal merchant shipping. Unscheduled, emergency deployments of

Army units also created disruptions to navy plans, as did other

occasional unexpected tasks. Contrary to the traditional historiography,

neither Admiral King’s unproven yet widely alleged Anglophobia, an

equally undocumented navy reluctance to accept British advice, nor a

preference for another strategy caused the delay in the inauguration of

coastal escort - of - convoy operations. The delay was due to a shortage of

escorts, and that resulted from understandably conflicting priorities, a

state of affairs that dictated all Allied strategy until 1944."

Other decisions perceived as questionable were his resistance to employ long range Liberators on Atlantic maritime patrols (thus allowing the U-boats a safe area in the middle of the Atlantic — the "Atlantic Gap"), the denial of adequate numbers of landing craft to the Allied invasion of Europe, and the reluctance to permit the Royal Navy's Pacific Fleet any role in the Pacific. In all of these instances, circumstances forced a re-evaluation or he was over - ruled. It has also been pointed out that King did not, in his post war report to the Secretary of the Navy, accurately describe the slowness of the American response to the off shore U-boat threat in early 1942.

It should be noted, however, employment of long range maritime patrol aircraft in the Atlantic was complicated by inter service squabbling over command and control (the aircraft belonged to the Army; the mission was the Navy's; Stimson and Arnold initially refused to release the aircraft.) Although King had certainly used the allocation of ships to the European Theater as leverage to get the necessary resources for his Pacific objectives, he provided (at General Marshall's request) an additional month's production of landing craft to support Operation Overlord. Moreover, the priority for landing craft construction was changed, a factor outside King's remit. The level of sea lift for Overlord turned out to be more than adequate.

The employment of British and Empire forces in the Pacific was a political matter. The measure was forced on Churchill by the British Chiefs of Staff, not only to re-establish British presence in the region, but to mitigate any perception in the U.S. that the British were doing nothing to help defeat Japan. King was adamant that naval operations against Japan remain 100% American, and angrily resisted the idea of a British naval presence in the Pacific at the Quadrant Conference in late 1944, citing (among other things) the difficulty of supplying additional naval forces in the theater (for much the same reason, Hap Arnold resisted the offer of RAF units in the Pacific). In addition, King (along with Marshall) had continually resisted operations that would assist the British agenda in reclaiming or maintaining any part of her pre-war colonial holdings in the Pacific or the Eastern Mediterranean. Roosevelt, however, overruled him and, despite King's reservations, the British Pacific Fleet accounted itself well against Japan in the last months of the war.

General Hastings Ismay, chief of staff to Winston Churchill, described King as:

tough as nails and carried himself as stiffly as a poker. He was blunt and stand - offish, almost to the point of rudeness. At the start, he was intolerant and suspicious of all things British, especially the Royal Navy; but he was almost equally intolerant and suspicious of the American Army. War against Japan was the problem to which he had devoted the study of a lifetime, and he resented the idea of American resources being used for any other purpose than to destroy the Japanese. He mistrusted Churchill's powers of advocacy, and was apprehensive that he would wheedle President Roosevelt into neglecting the war in the Pacific.

Despite British perceptions, King was a strong believer in the Germany first strategy. However, his natural aggression did not permit him to leave resources idle in the Atlantic that could be utilized in the Pacific, especially when "it was doubtful when — if ever — the British would consent to a cross - Channel operation". King once complained that the Pacific deserved 30% of Allied resources but was getting only 15%. When, at the Casablanca Conference, he was accused by Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke of favoring the Pacific war, the argument became heated. The combative General Joseph Stilwell wrote: "Brooke got nasty, and King got good and sore. King almost climbed over the table at Brooke. God, he was mad. I wished he had socked him."

Following Japan's defeat at the Battle of Midway, King advocated (with Roosevelt's tacit consent) the invasion of Guadalcanal. When General Marshall resisted this line of action (as well as who would command the operation), King stated that the Navy (and the Marines) would then carry out the operation by themselves, and instructed Admiral Nimitz to proceed with the preliminary planning. King eventually won the argument, and the invasion went ahead with the backing of the Joint Chiefs. It was ultimately successful, and was the first time the Japanese lost ground during the war. For his attention to the Pacific Theater he is highly regarded by some Australian war historians.

In spite of (or perhaps partly because of) the fact that the two men did not get along, the combined influence of King and General Douglas MacArthur increased the allocation of resources to the Pacific War.

Other controversies involving King include:

- The United States Coast Guard Auxiliary aka "Corsair Fleet".

- Captain Charles B. McVay III court-martial.