<Back to Index>

- Painter Francisco de Zurbarán, 1598

PAGE SPONSOR

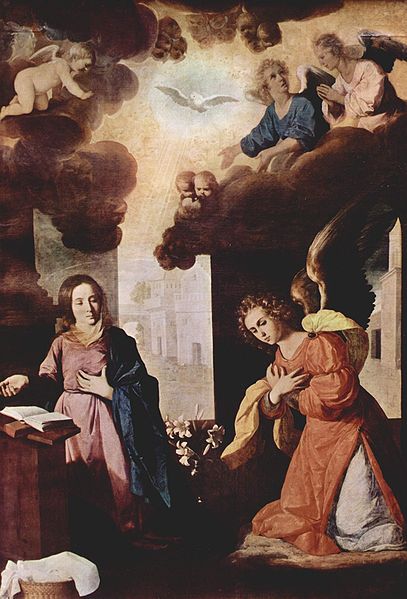

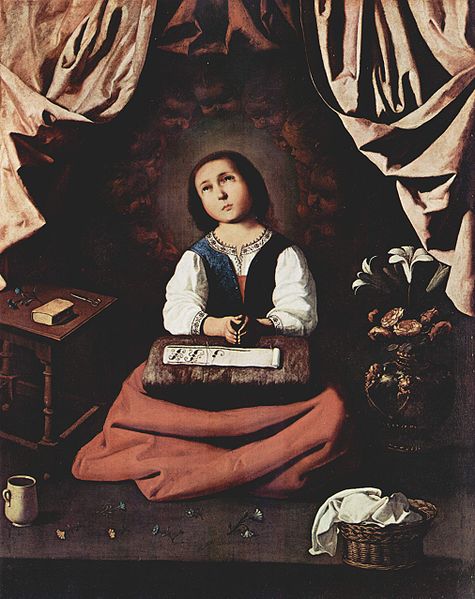

Francisco de Zurbarán (baptized November 7, 1598; died August 27, 1664) was a Spanish painter. He is known primarily for his religious paintings depicting monks, nuns, and martyrs, and for his still lifes. Zurbarán gained the nickname Spanish Caravaggio, owing to the forceful, realistic use of chiaroscuro in which he excelled.

Zurbarán was born in 1598 in Fuente de Cantos, Extremadura; he was baptized on November 7 of that year. His parents were Luis de Zurbarán, a haberdasher, and his wife, Isabel Márquez. In childhood he set about imitating objects with charcoal. In 1614 his father sent him to Sevilla to apprentice for three years with Pedro Díaz de Villanueva, an artist of whom very little is known.

While

in Sevilla, Zurbarán married Leonor de Jordera, by whom he had

several children. Towards 1630 he was appointed painter to Philip IV

of Spain, and there is a story that on one occasion the

sovereign laid his hand on the artist's shoulder, saying "Painter to the

king, king of painters." After 1640 his austere, harsh, hard edged

style was unfavorably compared to the sentimental religiosity of Murillo and Zurbarán's reputation declined. It was only in 1658, late in Zurbarán's life that he moved to Madrid in search of work and renewed his contact with Velázquez. Zurbarán died in poverty and obscurity.

It is unknown whether Zurbarán had the opportunity to copy the paintings of Caravaggio; at any rate, he adopted Caravaggio's realistic use of chiaroscuro and tenebrism. The painter who may have had the greatest influence on his characteristically severe compositions was Juan Sánchez Cotán. Polychrome sculpture — which by the time of Zurbarán's apprenticeship had reached a level of sophistication in Sevilla that surpassed that of the local painters — provided another important stylistic model for the young artist; the work of Juan Martínez Montañés is especially close to Zurbarán's in spirit.

He

painted directly from nature, and he made great use of the lay - figure

in the study of draperies, in which he was particularly proficient. He

had a special gift for white draperies; as a consequence, the houses of

the white - robed Carthusians are

abundant in his paintings. To these rigid methods, Zurbarán is

said to have adhered throughout his career, which was prosperous, wholly

confined to Spain, and varied by few incidents beyond those of his

daily labor. His subjects were mostly severe and ascetic religious

vigils, the spirit chastising the flesh into subjection, the

compositions often reduced to a single figure. The style is more

reserved and chastened than Caravaggio's, the tone of color often quite

bluish. Exceptional effects are attained by the precisely finished

foregrounds, massed out largely in light and shade.

In 1627 he painted the great altarpiece of St. Thomas Aquinas, now in the Museum of Fine Arts of Sevilla; it was executed for the church of the college of that saint there. This is Zurbarán's largest composition, containing figures of Christ, the Madonna, various saints, Charles V with knights, and Archbishop Deza (founder of the college) with monks and servitors, all the principal personages being more than life size. It had been preceded by numerous pictures of the screen of St. Peter Nolasco in the cathedral.

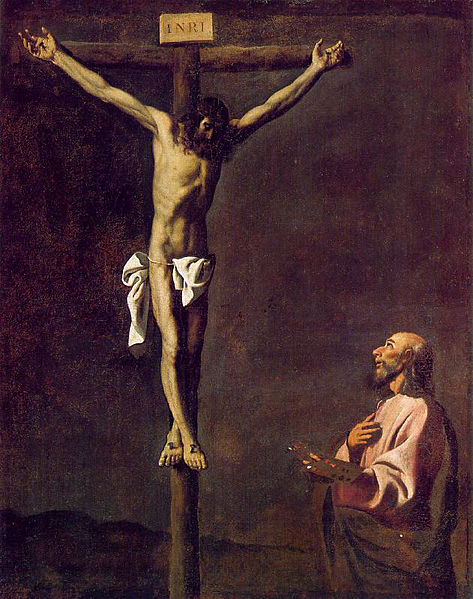

In Santa Maria de Guadalupe he painted various large pictures, eight of which relate to the history of St. Jerome; and in the church of Saint Paul, Sevilla, a famous figure of the Crucified Savior, in grisaille, creating an illusion of marble. In 1633 he finished the paintings of the high altar of the Carthusians in Jerez. In the palace of Buenretiro, Madrid, are four large canvases representing the Labors of Hercules, an unusual instance of non - Christian subjects from the hand of Zurbarán. A fine example of his work is in the National Gallery, London: a whole - length, life - sized figure of a kneeling Franciscan holding a skull.

His principal pupils were Bernabe de Ayala and the Polanco brothers.