<Back to Index>

- Writer and Painter Ardengo Soffici, 1879

- Writer and Critic Giovanni Papini, 1881

PAGE SPONSOR

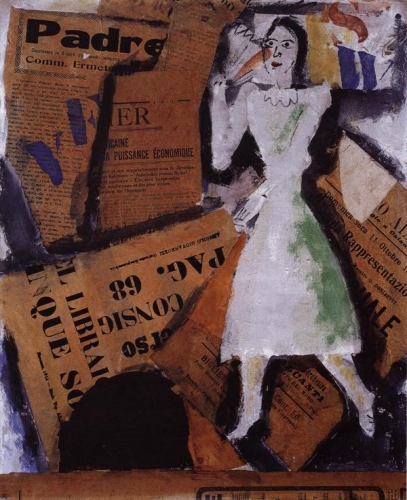

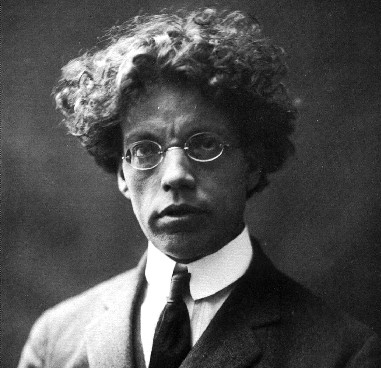

Ardengo Soffici (April 7, 1879 – August 12, 1964), was an Italian writer, painter and Fascist intellectual.

Soffici was born in Rignano sull' Arno, near Florence. In 1893 his family moved to the latter city, where he studied at the Accademia from 1897 and later at the Scuola Libera del Nudo.

In 1900 he moved from Florence to Paris, where he lived for seven years, working for Symbolist journals. While in Paris he became acquainted with Braque, Derain, Picasso, Gris and Apollinaire.

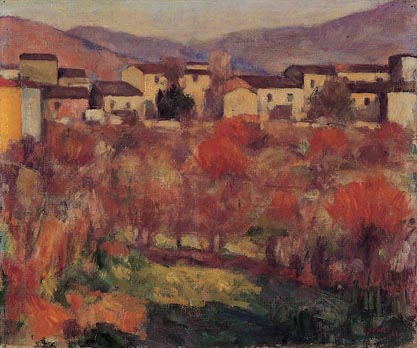

On returning to Italy in 1907, Soffici settled in Poggio a Caiano in the countryside near Florence (where he lived for the rest of his life) and wrote articles on modern artists for the first issue of the political and cultural magazine La Voce.

In 1910 he organized an exhibition of Impressionist painting in Florence in association with La Voce, devoting an entire room to the sculptor Medardo Rosso.

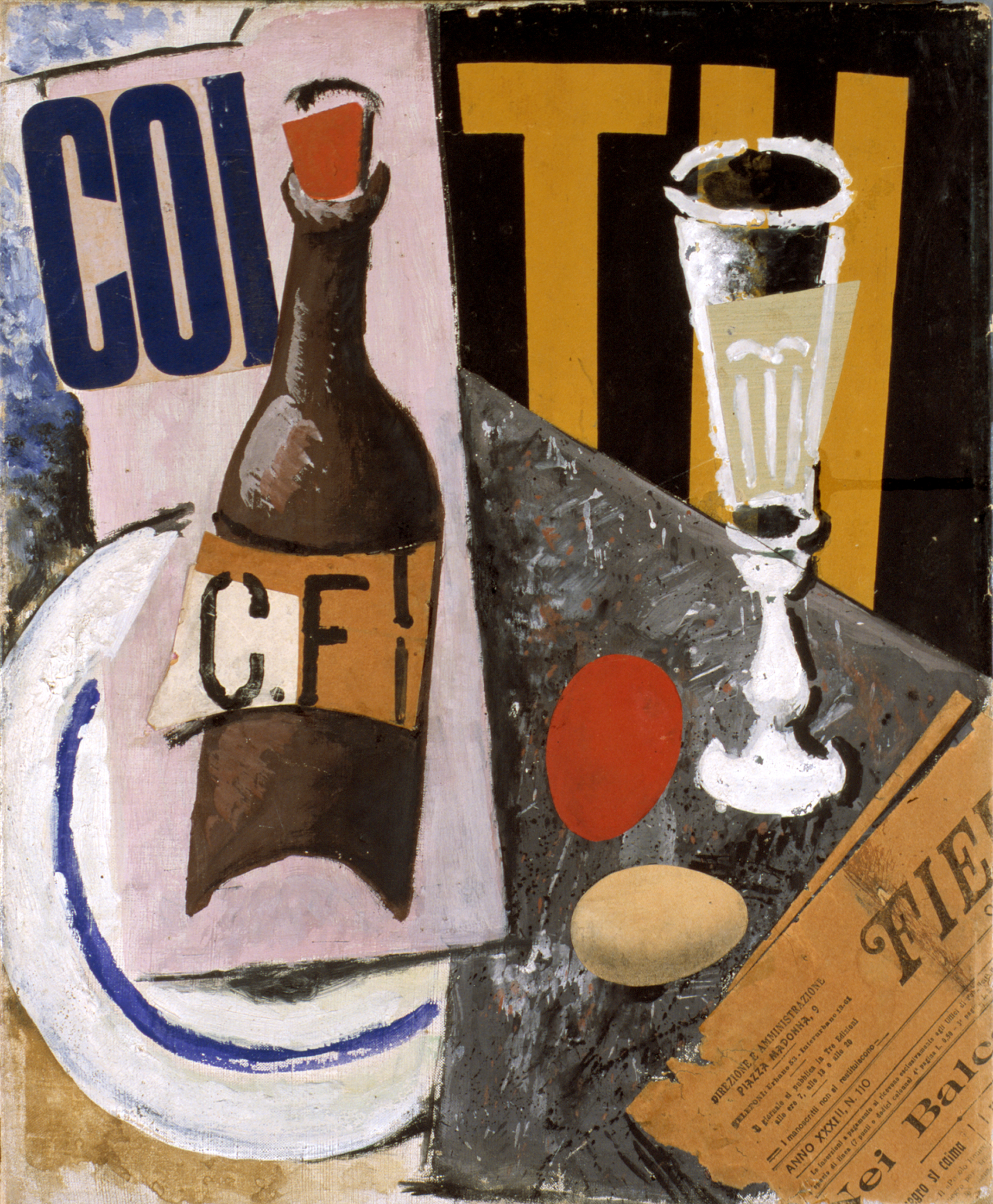

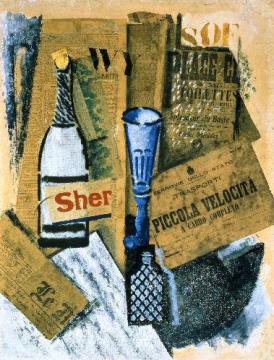

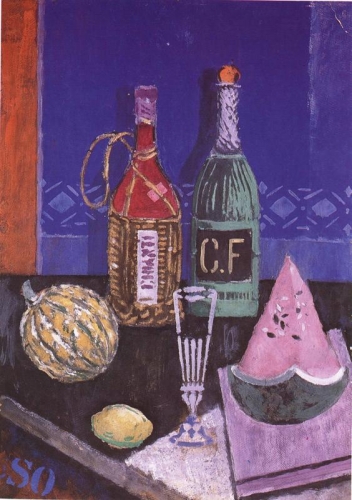

In August 1911 he wrote an article in La Voce on Picasso and Braque, which probably influenced the Futurists in the direction of Cubism. At this time Soffici considered Cubism to be an extension of the partial revolution of the Impressionists. In 1912 - 1913 Soffici painted in a Cubist style.

After visiting the Futurists' Exhibition of Free Art in Milan, he wrote a hostile review in La Voce. The leading Futurists Marinetti, Boccioni and Carrà, were so incensed by this that they immediately boarded a train for Florence and assaulted Soffici and his La Voce colleagues at the Caffè Giubbe Rosse. Reviewing the Futurists' Paris exhibition of 1912 in his article Ancora del Futurismo (Futurism Again) he dismissed their rhetoric, publicity - seeking and their art, but granted that, despite its faults, Futurism was "a movement of renewal, and that is excellent".

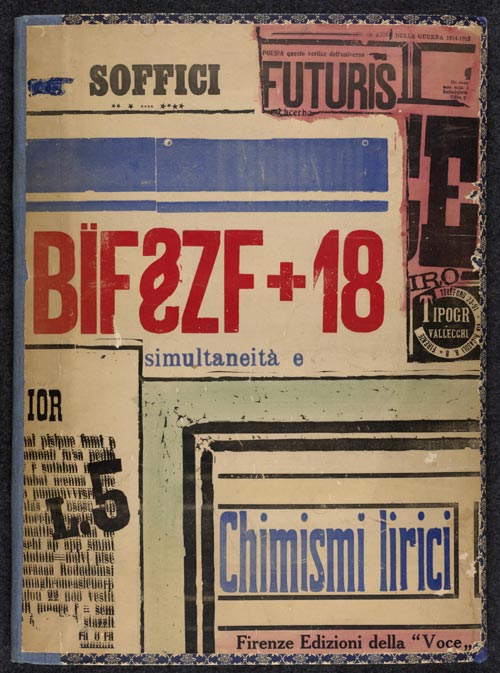

Gino Severini was dispatched from Milan to Florence to make peace with Soffici on behalf of the Futurists – the Peace of Florence, as Boccioni called it. After these diplomatic overtures, Soffici, together with Giovanni Papini, Aldo Palazzeschi and Italo Tavolato withdrew from La Voce in 1913 to form a new periodical, Lacerba, which would concentrate entirely on art and culture. Soffici published "Theory of the movement of plastic Futurism" in Lacerba, accepting that Futurism had reconciled what had previously seemed irreconcilable, Impressionism and Cubism. By its fifth issue Lacerba wholly supported the Futurists. Soffici's paintings in 1913 – e.g., Linee di una strada and Sintesi di una pesaggio autumnale – showed the influence of the Futurists in method and title and he exhibited with them.

In 1914, personal quarrels and artistic differences between the Milan Futurists and the Florence group around Soffici, Papini and Carlo Carrà, created a rift in Italian Futurism. The Florence group resented the dominance of Marinetti and Boccioni, whom they accused of trying to establish "an immobile church with an infallible creed", and each group dismissed the other as passéiste.

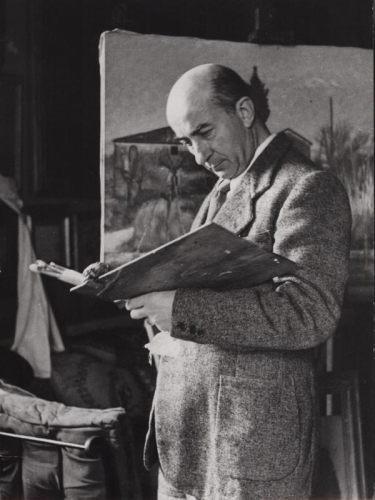

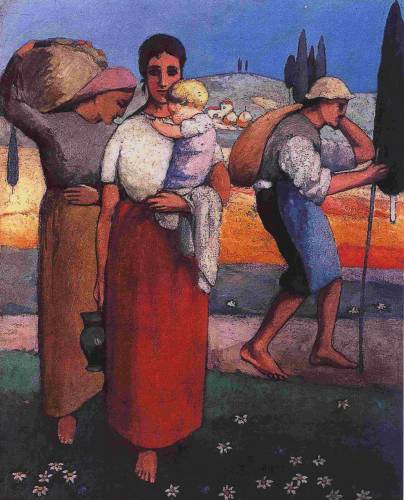

After serving in the First World War, Soffici abandoned Futurism and, discovering a new reverence for Tuscan tradition, became associated with the "return to order" which manifested itself in the naturalistic landscapes which therafter dominated his work. At that time he lived in Poggio a Caiano, painting nature and traditional Tuscan farm scenes. There, in 1926, he discovered the young artist Quinto Martini when the latter went to visit Soffici's workshop with his work. Looking at Martini's first experiments, Soffici recognized the kind of genuine and intimate traits he was seeking and became his mentor.

Soffici was one of the signatories of Gentile's 1925 Fascist manifesto. He regarded the United States of America as "false", "transitory" and "ephemeral". It was a "non - civilization" where the spirituality of art was suffocated by the barbaric vulgarity of a people without history and without tradition, and incapable, therefore, of creating a true civilization. To Soffici and other moralists of Italian Fascism, US civilization represented "impending modernity", that is to say, a violent negation of the Italian genius; it was necessary to wage a holy war against the American monster to save Italian civilization.

He died at the Italian holiday resort of Forte dei Marmi.

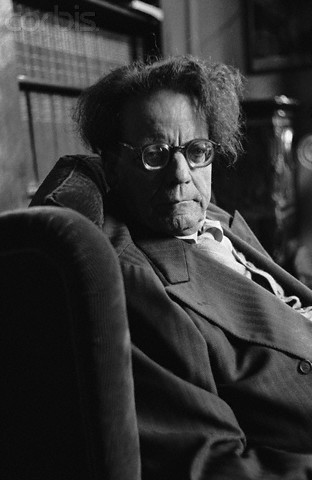

Giovanni Papini (January 9, 1881 – July 8, 1956) was an Italian journalist, essayist, literary critic, poet, and novelist.

Born in Florence as the son of a modest furniture retailer (and former member of Giuseppe Garibaldi's Redshirts) from Borgo degli Albizi, Papini was baptized secretly to avoid the aggressive atheism of his father, and he lived a rustic, lonesome, and precociously introspective childhood. From that time onwards he felt a strong aversion to all beliefs, to all churches, as well as to any form of servitude (which he saw as connected to religion); he also became enchanted with the impossible idea of writing an encyclopedia wherein all cultures would be summarized.

Trained

as a schoolteacher, he taught for a few years after 1899, then became a

librarian. The literary life attracted Papini, who founded the magazine Il Leonardo, together with Giuseppe Prezzolini, in 1903, then joined Enrico Corradini's group as co-editor of Il Regno. He started publishing short stories and essays: in 1903, Il tragico quotidiano ("The Tragic Everyday"), in 1907 Il pilota cieco ("The Blind Pilot") and Il crepuscolo dei filosofi ("The Twilight of the Philosophers"). The latter constituted a polemic with established and diverse intellectual figures, such as Immanuel Kant, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Auguste Comte, Herbert Spencer, Arthur Schopenhauer, and Friedrich Nietzsche - Papini proclaimed to the death of philosophers and the demolition of thinking itself. He briefly flirted with Futurism and other violent and liberating forms of Modernism (Papini is the character in several poems of the period written by Mina Loy).

After leaving Il Leonardo in 1907, Giovanni Papini founded Anima together with Giovanni Amendola. His Parole e sangue ("Words and Blood") essay of the period showed his unequivocal atheism, summoned in his advice:

- Humans: become atheists each and all!... God will nevertheless welcome you with all [H]is heart!

Furthermore, Papini sought to create scandal by speculating that Jesus and John the Apostle had a homosexual relationship.

He broke off with Prezzolini, co-editor of Anima, and the paper ceased to appear. Papini founded Lacerba, published between 1913 and 1915 (right before Italy's entry into World War I). In 1912, he published his best known work, the autobiography Un uomo finito (tr.: "The Failure").

His 1915 collection of prose poetry Cento pagine di poesia, followed by Buffonate and Maschilità, and the 1916 Stroncature - Papini faced Giovanni Boccaccio, William Shakespeare, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, but also contemporaries such as Benedetto Croce and Giovanni Gentile, and less prominent disciples of Gabriele D'Annunzio. He published verse in 1917, grouped under the title Opera prima. In 1921, Papini announced his newly found Roman Catholicism, publishing the international bestseller essay Storia di Cristo ("Life of Christ").

After further verse works, he published the satire Gog (1931) and the essay Dante vivo (tr. "If Dante Were Alive"; 1933).

He moved towards Fascism, and his beliefs earned him a teaching position at the University of Bologna in 1935 (although his studies only qualified him for primary school teaching); the Fascist authorities confirmed Papini's "impeccable reputation" through the appointment. In 1937, Papini published the only volume of his History of Italian Literature, which he dedicated to Benito Mussolini: "to Il Duce, friend of poetry and of the poets", being awarded top positions in academia, especially in the study of Italian Renaissance. An Antisemite, he believed in an international plot of Jews, applauding the racial discrimination laws enforced by Mussolini in 1938. Papini was the vice president of the European Writers' League, which was founded by Joseph Goebbels in 1941 / 42. When the Fascist regime crumbled (1943), Papini entered the Franciscan convent in La Verna.

Largely discredited at the end of World War II, he was defended by the Catholic political right. His work concentrated on different subjects, including a biography of Michelangelo, while he continued to publish dark and tragic essays. He collaborated with Corriere della Sera, contributing articles that were published as a volume after his death.

According to The Spectator, NATO allegedly encouraged Papini, in 1951, to publish a fake interview with Pablo Picasso, to dramatically undercut his pro - Communist image. In 1962, the artist asked his biographer Pierre Daix, to expose the fake interview, which he did in Les Lettres Françaises.