<Back to Index>

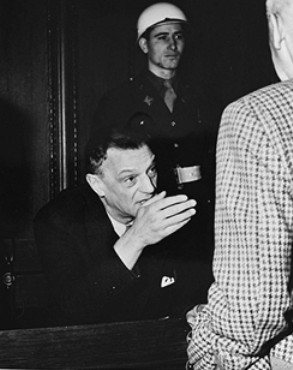

- Federal Chancellor of Austria and Reich Minister of Foreign Affairs Arthur Seyss - Inquart, 1892

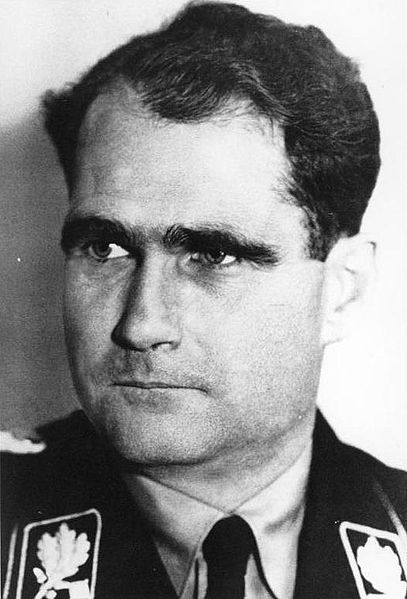

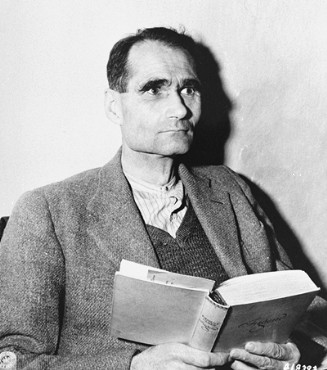

- Deputy Führer Rudolf Walter Richard Hess, 1894

PAGE SPONSOR

Arthur Seyss - Inquart (in German: Seyß - Inquart) (22 July 1892 – 16 October 1946) was a Chancellor of Austria, lawyer and later Nazi official in pre - Anschluss Austria, the Third Reich and for wartime Germany in Poland and the Netherlands. At the Nuremberg Trials, he was found guilty of crimes against humanity and later executed.

Seyss - Inquart was born in 1892 in Stonařov (German: Stannern), Moravia, then part of the Austro - Hungarian Empire, to the ethnic Czech school principal Emil Zajtich and his German speaking wife Auguste Hýrenbach. The family moved to Vienna in 1907. Seyss - Inquart later went to study law at the University of Vienna. At the beginning of World War I in August 1914 Seyss - Inquart enlisted with the Austrian Army and was given a commission with the Tyrolean Kaiserjäger, subsequently serving in Russia, Romania and Italy. He was decorated for bravery on a number of occasions and while recovering from wounds in 1917 he completed his final examinations for his degree. Seyss - Inquart had five older siblings: Hedwig (born 1881), Richard (born 3 April 1883, became a Catholic priest, but left the Church and ministry, married in civil ceremony and became Oberregierungsrat and prison superior by 1940 in the Ostmark), Irene (born 1885), Henriette (born 1887) and Robert (born 1891).

In 1911, Seyss - Inquart met Gertrud Maschka. The couple married in 1916 and had three children: Ingeborg Caroline Auguste Seyss - Inquart (born 18 September 1917), Richard Seyss - Inquart (born 22 August 1921) and Dorothea Seyss - Inquart (born 7 May 1928).

He went into law after the war and in 1921 set up his own practice. During the early years of the Austrian First Republic, he was close to the Vaterländische Front. A successful lawyer, he was invited to join the cabinet of Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss in 1933. Following Dollfuss' murder in 1934, he became a State Councillor from 1937 under Kurt von Schuschnigg. He was not initially a member of the Austrian National Socialist party, though he was sympathetic to many of their views and actions. By 1938, however, Seyss - Inquart knew which way the political wind was blowing and became a respectable frontman for the Austrian National Socialists.

In February 1938, Seyss - Inquart was appointed Minister of the Interior by Schuschnigg, after Adolf Hitler had

threatened Schuschnigg with military actions against Austria in the

event of non - compliance. On March 11, 1938, faced with a German invasion

aimed at preventing a plebiscite of

independence, Schuschnigg resigned as Austrian Chancellor and

Seyss - Inquart was reluctantly appointed to the position by Austrian President Wilhelm Miklas. On the next day German troops crossed the border of Austria, at the telegraphed invitation

of Seyss - Inquart, the latter communique having been arranged after the

troops had begun to march, so as to justify the action in the eyes of

the international community. Before his triumphant entry into Vienna,

Hitler had planned to leave Austria as a suppliant state, with an

independent but loyal government. He was carried away, however, by the

wild reception given to the German army by the majority of the Austrian

population, and shortly decreed that Austria would be incorporated into

the Third Reich as the province of Ostmark (Anschluss). Only then, on 13 March 1938, did Seyss - Inquart join the National Socialist party.

Seyss - Inquart drafted the legislative act reducing Austria to a province of Germany and signed it into law on 13 March. With Hitler's approval he remained head (Reichsstatthalter) of the newly named Ostmark, with Ernst Kaltenbrunner his chief minister and Josef Burckelas Commissioner for the Reunion of Austria (concerned with the "Jewish Question"). Seyss - Inquart also received an honorary SS rank of Gruppenführer and in May 1939 he was made a Minister without portfolio in Hitler's cabinet.

Following the invasion of Poland, Seyss - Inquart became administrative chief for Southern Poland, but did not take up that post before the General Government was created, in which he became a deputy to the Governor General Hans Frank. It is claimed that he was involved in the movement of Polish Jews into ghettos, in the seizure of strategic supplies and in the "extraordinary pacification" of the resistance movement.

Following the capitulation of the Low Countries Seyss - Inquart was appointed Reichskommissar for the Occupied Netherlands in May 1940, charged with directing the civil administration, with creating close economic collaboration with Germany and with defending the interests of the Reich. He supported the Dutch NSB and allowed them to create a paramilitary Landwacht, which acted as an auxiliary police force. Other political parties were banned in late 1941 and many former government officials were imprisoned at Sint - Michielsgestel. The administration of the country was controlled by Seyss - Inquart himself and he answered directly to Hitler. He oversaw the politicization of cultural groups "right down to the chess players' club" through the Nederlandsche Kultuurkamer and set up a number of other politicized associations.

He introduced measures to combat resistance and when a widespread strike took place in Amsterdam, Arnhem and Hilversum in May 1943 special summary court martial procedures were brought in and a collective fine of 18 million guilders was imposed. Up until the liberation, Seyss - Inquart condoned the execution of around 800 people, although some reports put this total at over 1,500, including the executions of people under the so-called "Hostage Law", the death of political prisoners who were close to being liberated, the Putten incident, and the reprisal executions of 117 Dutchmen for the attack on SS and Police Leader Hanns Albin Rauter. Although the majority of Seyss - Inquart's powers were transferred to the military commander in the Netherlands and the Gestapo in July 1944, he remained a force to be reckoned with.

There were two small concentration camps in the Netherlands – KZ Herzogenbusch near Vught, Kamp Amersfoort near Amersfoort, and a "Jewish assembly camp" at (camp) Westerbork; there were a number of other camps variously controlled by the military, the police, the SS or Seyss - lnquart's administration. These included a "voluntary labor recruitment" camp at Ommen (Camp Erika). In total around 530,000 Dutch civilians forcibly worked for the Germans, of whom 250,000 were sent to factories in Germany. There was an unsuccessful attempt by Seyss - Inquart to send only workers aged 21 to 23 to Germany, and he refused demands in 1944 for a further 250,000 Dutch workers and in that year sent only 12,000 people.

Seyss - Inquart was an unwavering anti - Semite: within a few months of his arrival in the Netherlands, he took measures to remove Jews from the government, the press and leading positions in industry. Anti - Jewish measures intensified after 1941: approximately 140,000 Jews were registered, a 'ghetto' was created in Amsterdam and a transit camp was set up at Westerbork. Subsequently, in February 1941, 600 Jews were sent to Buchenwald and Mauthausen concentration camps. Later, the Dutch Jews were sent to Auschwitz. As Allied forces approached in September 1944, the remaining Jews at Westerbork were removed to Theresienstadt. Of 140,000 registered, only 30,000 Dutch Jews survived the war.

When Hitler committed suicide in April 1945, Seyss - Inquart declared the setting up of a new German government under Admiral Karl Dönitz, in which he was to act as the new Foreign Minister, replacing Joachim von Ribbentrop, who had long since lost Hitler's favor. It was a tribute to the high regard Hitler felt for his Austrian comrade, at a time when he was rapidly disowning or being abandoned by so many of the other key lieutenants of the Third Reich. Unsurprisingly, at such a late stage in the war, Seyss - Inquart failed to achieve anything in his new office, and was captured shortly before the end of hostilities. The Dönitz government lasted no more than 20 days.

When the Allies advanced into the Netherlands in late 1944, the Nazi regime had attempted to enact a scorched earth policy, and some docks and harbors were destroyed. Seyss - Inquart, however, was in agreement with Armaments Minister Albert Speer over the futility of such actions, and with the open connivance of many military commanders, they greatly limited the implementation of the scorched earth orders. At the very end of the "hunger winter" in April 1945, Seyss - Inquart was with difficulty persuaded by the Allies to allow airplanes to drop food for the hungry people of the occupied northwest of the country. Although he knew the war was lost, Seyss - Inquart did not want to surrender. This led General Walter Bedell Smith to snap: "Well, in any case, you are going to be shot". "That leaves me cold", Seyss - Inquart replied, to which Smith then retorted: "It will".

He

remained Reichskommissar until 7 May 1945, when, after a meeting with

Karl Dönitz to confirm his blocking of the scorched earth orders,

he was arrested on the Elbe Bridge at Hamburg by two members of the

Royal Welsh Fusiliers, one of whom was Norman Miller (birth name:

Norbert Mueller), a German Jew from Nuremberg who had escaped to Britain

at the age of 15 on a kinder transport just before the war and then

returned to Germany as part of the British occupation forces. Miller's entire family had been killed at the Jungfernhof Camp in Riga, Latvia in March 1942.

At the Nuremberg Trials, Seyss - Inquart was defended by Gustav Steinbauer and faced charges of conspiracy to commit crimes against peace; planning, initiating and waging wars of aggression; war crimes; and crimes against humanity.

During the trial, Gustave Gilbert, an American army psychologist, was allowed to examine the Nazi leaders who were tried at Nuremberg for war crimes. Among other tests, a German version of the Wechsler - Bellevue IQ test was administered. Arthur Seyss - Inquart scored 141, the second highest among the Nazi leaders tested, behind Hjalmar Schacht.

Seyss - Inquart was found guilty of all charges, save conspiracy and sentenced to death by hanging.

Upon hearing of his death sentence, Seyss - Inquart was fatalistic: "Death by hanging... well, in view of the whole situation, I never expected anything different. It's all right." He was hanged on 16 October 1946, at the age of 54, together with nine other Nuremberg defendants. He was the last to mount the scaffold, and his last words were "I hope that this execution is the last act of the tragedy of the Second World War and that the lesson taken from this world war will be that peace and understanding should exist between peoples. I believe in Germany."

Before his execution, Seyss - Inquart had returned to Catholicism, receiving absolution in the sacrament of confession from prison chaplain Father Bruno Spitzl.

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (26 April 1894 in Alexandria, Khedivate of Egypt – 17 August 1987 in West Berlin, West Germany) was a prominent Nazi politician who was Adolf Hitler's deputy in the Nazi Party during the 1930s and early 1940s. On the eve of war with the Soviet Union, he flew solo to Scotland in an attempt to negotiate peace with the United Kingdom, but was arrested and became a prisoner of war. Hess was put on trial at Nuremberg and sentenced to life imprisonment, which he served at Spandau Prison, Berlin, where he died in 1987. There have been conspiracy theories linked to Hess. After World War II Winston Churchill wrote of Hess, "He was a medical and not a criminal case, and should be so regarded."

On 27 – 28 September 2007, numerous British news services published descriptions of disagreement between his Western and Soviet captors over his treatment and how the Soviet captors were steadfast in denying his release. In July 2011, the remains of Rudolf Hess were exhumed from a grave in Bavaria after it became a focus of a pilgrimage for neo-Nazis.

Hess was born in Alexandria, Egypt, the eldest of four children, to Fritz H. Hess, a prosperous German Lutheran importer / exporter from Bavaria, and Clara (née Münch). The family lived in luxury on the Egyptian coast, near Alexandria, and visited Germany often during the summers, allowing the Hess children to learn the German language and to absorb German culture. The family moved back to Germany in 1908, where Rudolf was subsequently enrolled in boarding school in Bad Godesberg, at the Evangelical School. Hess showed aptitude in science and mathematics, and expressed interest in becoming an astronomer. However, his father wished him to eventually continue the family business, Hess & Co., and in 1911 convinced Rudolf to study business for one year in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, at the Ecole Supérieure de Commerce.

Hess joined the Hamburg trading company Feldt, Stein & Co. as an apprentice in 1912. At the outbreak of World War I he enlisted in the 7th Bavarian Field Artillery Regiment, became an infantryman and was awarded the Iron Cross, second class. He saw heavy action both on the Western Front (at Ypres and Verdun) and in the Carpathian Mountains. After being wounded on several occasions — including a chest wound severe enough to prevent his return to the front as an infantryman — he transferred to the Imperial Air Corps (after being rejected once). He then took aeronautical training and served as a pilot in an operational squadron, Jasta 35b (Bavarian), with the rank of lieutenant from 16 October 1918. He won no victories. The war ended on 11 November 1918.

On 20 December 1927, Hess married 27 year old Ilse Pröhl (22 June 1900 – 7 September 1995) from Hannover. They had a son, Wolf Rüdiger Hess (18 November 1937 – 24 October 2001).

After the war, the successful Hess family business collapsed. Hess went to Munich, and took a job at a textile importing firm. He joined the Freikorps. He also joined the Thule Society, a right wing völkisch occult - mystical organization. After the end of the war, Bavaria underwent fierce infighting between right wing groups and left wing forces, some of which were Soviet backed.

In autumn of 1919, Hess left his job and enrolled in the University of Munich where he studied political science, history, geography, and geopolitics under Professor Karl Haushofer,

whom he had first met in the summer of 1919 in a social setting. From

their first meeting, Hess became a disciple of Karl Haushofer, the two

became close friends, and their families would also become close in the

ensuing years, as Hess and Karl's son Albrecht Haushofer also developed a strong friendship.

After hearing Adolf Hitler, a powerful orator, speak for the first time in May 1920 at a Munich rally, Hess became completely devoted to him, and spent much of his time and effort for the next several years organizing for Hitler at the local level in Bavaria. Hess joined the fledgling Nazi Party in 1920 as one of its first members. Hess introduced Karl Haushofer to Hitler in the spring of 1921, following a rally at a beer hall. This was a critical and vital development in the eventual Nazi rise to power. Haushofer and Hitler connected immediately on a personal level. Haushofer's geopolitical theories found a strong convert in Hitler, who used this material to form the basis of his own plans for the rebuilding of Germany; Hitler soon began using Haushofer's material in his speeches, which drew ever larger audiences and attention. Haushofer would become a close adviser to Hitler, and assume prominence in Germany with Hitler's rise.

Hess commanded an SA battalion during the Hitler led Beer Hall Putsch in 1923, which failed. Hess served seven and a half months in Landsberg Prison; Hitler was sentenced to five years in the same prison, but eventually served just nine months. Acting as Hitler's private secretary in prison, Hess transcribed and partially edited Hitler's book Mein Kampf. While in prison, Hitler and Hess were frequently visited and tutored by Karl Haushofer. Hess also introduced Hitler at early Nazi Party rallies.

Hess retained his interest in flying after the end of his active military career, and competed successfully in several races during the 1920s and 1930s latterly in a BFW M35b monoplane. He also flew the Messerschmitt Bf 108 and Messerschmitt Bf 110 which he learned to fly under the tutelage of the company chief test pilot Willi Stör.

Writing in Mein Kampf, Hitler said, 'under the old regime there was Prince Eulenburg, under the new, there is Rudolf Hess'. Anton Drexler (known for being Adolf Hitler's mentor during his early days in politics) and

his group resented Hess, considering him 'too intellectual'.

Eventually, Hess became the third most powerful man in Germany, behind Hitler and Hermann Göring. Soon after Hitler assumed dictatorial powers, beginning in early 1933, Hess was named "Deputy to the Fuhrer". Hess had a privileged position as Hitler's deputy in the early years of the Nazi movement and in the early years of the Third Reich. For instance, he had the power to take "merciless action" against any defendant who he thought got off too lightly — especially in cases of those found guilty of attacking the party, Hitler or the state. Hess also played a prominent part in the creation of the Nuremberg Laws in 1935. Hitler biographer John Toland described Hess's political insight and abilities as somewhat limited.

Hess had extensive dealings with senior leaders of major European nations during the 1930s. His education, family man image, high office, and calm, forthright manner all served to make him the more respectful and respectable representative of the often otherwise crude and vulgar Nazis. Compared with other Nazi leaders, Hess had a good reputation among foreign leaders.

Within Germany, Hess was somewhat marginalized as the 1930s progressed, as foreign policy took greater prominence. His alienation increased during the early years of the war, as attention and glory were focused on military leaders, along with Hermann Göring, Joseph Goebbels and Heinrich Himmler. Those three Nazi leaders in particular had much higher profiles than Hess. Though Hess worshiped Hitler more than the others, he was not nakedly ambitious and did not crave power in the same manner they did. However, as the Deputy Fuhrer, he was definitely not a figurehead. Hess held as much power as the other Nazi leaders, if not more, under Hitler. He controlled who could get an audience with the Fuhrer, as well as passing and vetoing proposed bills, and managing party activities. Hitler appointed Hess as "Minister Without Portfolio".

On 1 September 1939, the day Germany invaded Poland and

launched World War II, Hitler announced that should anything happen to

both him and Göring, Hess would be next in the line of succession.

Like Goebbels, Hess was privately distressed by the war with the United Kingdom because he, influenced by his academic advisor and in line with earlier statements by Hitler himself, hoped that Britain would accept Germany as an ally. Hess may have hoped to score a diplomatic victory by sealing a peace between the Third Reich and Britain, using the contact his adviser Albrecht Haushofer had made in Nazi Germany, just before the war, with Douglas Douglas - Hamilton, 14th Duke of Hamilton.

On 10 May 1941, at about 6:00pm, Hess took off from Augsburg in a Messerschmitt Bf 110 (radio code VJ+OQ) which he had equipped with drop tanks to increase its range. Goering ordered the General of the Fighter Arm to

stop him but squadron leaders were ordered to scramble only one or two

fighters, since Hess's particular aircraft could not be distinguished

from others and he was soon out of their range over the North Sea.

Hess flew from Augsburg via Darmstadt and Bonn towards the Zuider Zee and then on a track towards the Shetland Islands, until he intercepted a Luftwaffe radio navigation signal transmitted from Kalundborg, Denmark. At that point he turned west towards the mainland of Britain. At about 22:08 Hess's aircraft was first detected by radar from RAF Station Ouston, north of Newcastle - upon - Tyne, at which time he was 70 mi (110 km) off the coast of Scotland, headed in a north - westerly direction towards the island of Lindisfarne. His flight was designated HOSTILE RAID 42J.[23]

Two Spitfires from Acklington in Northumberland which were already airborne received orders to intercept the unidentified aircraft, while a third was scrambled from Acklington. None of the three managed to sight the Bf 110 which dived to lose altitude after crossing the coast, and was subsequently sighted by a Royal Observer Corps post near Chatton in Northumberland (12.5 mi (20.1 km) inland) at 22:25, flying at only 50 ft (15 m).

Over Lanarkshire, south of Glasgow, Hess managed to identify what he thought was Dungavel, the residence of the Duke of Hamilton. However, he had in fact sighted Eaglesham House, near the village of Eaglesham.

To more precisely confirm his position he continued to fly on, over the

Ayrshire coast where at 22:35 he avoided contact with a RAF Defiant nightfighter which had been scrambled from RAF Prestwick to intercept the intruder. Shortly

afterwards, Hess abandoned the Bf 110 and landed by parachute near the

village of Eaglesham, injuring his ankle on landing.

Hess landed near Floors Farm, Eaglesham, where he was discovered removing his parachute harness by local ploughman David McLean. Hess identified himself as "Hauptmann Alfred Horn", and said that he had an important message for the Duke of Hamilton. McLean helped Hess to his home nearby then contacted the local Home Guard unit. Hess was then escorted under guard to the local Home Guard headquarters in Busby, East Renfrewshire, and from there to the Battalion HQ in Giffnock, where he arrived shortly after midnight. At Giffnock he was briefly questioned by Major Donald, the Assistant Group Officer of the Glasgow Royal Observer Corps. Hess gave a short description of his flight and repeated that he had "a secret and vital message" for the Duke of Hamilton and that he must see him immediately. The message was described as being "in the highest interest of the British Air Force", but Hess declined to go into any detail.

Hess was handed over to the Army and taken to Maryhill Barracks, Glasgow, where he again requested that the Duke should speak to him alone. Hamilton was informed of the prisoner and visited him whereupon he revealed his true identity. Shortly afterwards, Hamilton summarized their conversation in a report to Winston Churchill, dictated at RAF Turnhouse. Hamilton stated that, based on Press photographs and a description of Hess given by Albrecht Haushofer, that "this prisoner was indeed Hess himself". Hamilton then flew to RAF Northolt, and on to Kidlington near Oxford, from where he was taken by car to meet Churchill at Ditchley Park.

The flight of Hess, but not his destination or fate, was first announced by Munich Radio in Germany on the evening of Monday, May 12. Hess's capture was reported at the time in the British and international media and farmhand David McLean claimed to have arrested Hess with his pitchfork.

The wreckage of the aircraft was salvaged by 63 Maintenance Unit between 11 and 16 May 1941. The aeroplane was found to be armed with machine guns in the nose but there was no ammunition on board.

Records released by the UK's National Archives confirm that Hess was on a peace mission. In early 1941 Germany tried to negotiate peace with Britain through diplomatic communications via Sweden. The Duke of Hamilton commenced libel action in 1941 / 42 and wanted to stand Hess in court as a witness. There is no evidence to implicate the Duke of Hamilton. National Archives files relating to Hess and concerning the nature and range of German peace feelers in early 1941 (C1687G, C1954, C2785G) were formerly closed until 2017, but were released in 2007.

In May 1943, the American Mercury magazine published a story from an anonymous source that indicated the British Secret Service lured Hess to Scotland to meet with Douglas Douglas - Hamilton, 14th Duke of Hamilton, a member of the Anglo - German Fellowship and that Hess was on a peace mission; this was denied by Hitler. The Queen's Lost Uncle, a television program broadcast in November 2003 and March 2005 on Britain's Channel 4, indicated involvement by Prince George, Duke of Kent. It appears that Hess was tricked into thinking he was in communication with the Duke of Hamilton who Hess was led to believe was an opponent of Winston Churchill.

Hess was quoted by his wife Ilse as saying:

"My coming to England in this way is, as I realize, so unusual that nobody will easily understand it. I was confronted by a very hard decision. I do not think I could have arrived at my final choice unless I had continually kept before my eyes the vision of an endless line of children's coffins with weeping mothers behind them, both English and German, and another line of coffins of mothers with mourning children."

Hitler granted Hess's wife a pension but stripped Hess of all of his party and state offices, and privately ordered him shot on sight if he ever returned to Germany. Martin Bormann succeeded Hess as deputy under a newly created title.

Hess's flight raised suspicions with Soviet leader Joseph Stalin that secret discussions were under way between Britain and Germany to attack the Soviet Union. Later, in a meeting with Stalin, Churchill would address the topic and find Stalin still believed secret agreements were discussed with Hess. "When I make a statement of facts within my knowledge I expect it to be accepted," Churchill responded to Stalin, again denying that the incident resulted in any communications with Nazi Germany. Files at The National Archives dated 1942 include Moscow Embassy correspondence concerning Hess; some pages are subject to non - disclosure under statute.

According to data published in a book about Wilhelm Canaris, a number of contacts between Britain and Germany were kept during the war.

Churchill sent Hess initially to the Tower of London, making Hess the last in the long line of prominent people to be held in the 900 year old fortress. Churchill gave orders that Hess was to be strictly isolated, but treated with dignity. He remained in the Tower until 20 May 1941. After being held in the Maryhill army barracks, he was transferred to Mytchett Place near Aldershot. He was kept under close guard. Frank Foley and two other MI6 officers were given the job of debriefing Hess — or "Jonathan", as he was now known. Churchill's instructions were that Hess should be strictly isolated, and that every effort should be taken to get any information out of him that might be useful.

During his time as a prisoner of war Hess was confined at Maindiff Court Military Hospital, Abergavenny, Wales, for treatment for insanity. He was treated well and enjoyed painting.

At the time of his capture, official London sources had claimed Hess was "sane and healthy" and had not brought any peace message. However, the Nazis claimed he had left behind a letter which "showed clearly traces of mental disorder which led to fears that Party Comrade Hess was a victim of hallucinations." In an official report to President Franklin Roosevelt "A Former Naval Person" wrote: "Hess seems in good health and not excited, and no ordinary signs of insanity can be detected."

On 15 October 1941, Hess made his first suicide attempt by throwing himself over the rail of the first floor balcony, but he only broke his leg.

Hess was interviewed by psychiatrist John Rawlings Rees, who had worked at the Tavistock Clinic prior to becoming a Brigadier in the British Army. Rees concluded that he was not insane, but certainly mentally ill and suffering from depression — probably due to the failure of his mission. Hess's diaries from his imprisonment in Britain after 1941 make many references to visits from Rees, whom he did not like and accused of poisoning him and "mesmerizing" him. Rees took part in the Nuremberg Trials of 1945.

Hess

was in captivity for almost four years of the war and thus he was

absent from most of it, in contrast to the others who stood accused at

Nuremberg. British government files released by The National Archives include

a note concerning Hess's war crimes trial in which Judge Jackson

considered whether Hess should be testified as insane. His case was

considered by the Attorney General.

Hess became a defendant at the Nuremberg Trials of the International Military Tribunal, on the insistence of the Soviet Union, despite his being in a state of almost complete forgetfulness. He was eventually flown to Nuremberg in October 1945. Hess regained his memory for a short period and was declared fit to stand trial. Partial memory loss returned and he went back into amnesia. He spent his time in court reading, occasionally laughing. In the British view, Hess was of unsound mind. Some of his last words before the tribunal were "I regret nothing".

In 1946, Hess was found guilty on two of four counts: crimes against peace (planning and preparation of aggressive war) and conspiracy with other German leaders to commit crimes. He was found not guilty of war crimes or crimes against humanity. Hess was given a life sentence.

Following the release in 1966 of Baldur von Schirach and Albert Speer, Hess was the sole remaining inmate of Spandau Prison, partly at the insistence of the Soviets. Guards reportedly said he degenerated mentally and lost most of his memory. For the next 8 years, his main companion was warden Eugene K. Bird, with whom he formed a close friendship. Bird wrote a 1974 book titled The Loneliest Man in the World: The Inside Story of the 30 - Year Imprisonment of Rudolf Hess about his relationship with Hess. Frank Keller, a former guard at Spandau, said that "Hess would march by himself in the jail courtyard every day".

In the third volume of his book The Second World War Winston Churchill wrote:

Reflecting upon the whole of the story, I am glad not to be responsible for the way in which Hess has been and is being treated. Whatever may be the moral guilt of a German who stood near to Hitler, Hess had, in my view, atoned for this by his completely devoted and frantic deed of lunatic benevolence. He came to us of his own free will, and, though without authority, had something of the quality of an envoy. He was a medical and not a criminal case, and should be so regarded.

In the early 1970s, the U.S., British and French governments had approached the Soviet government to propose that Hess be released on humanitarian grounds due to his age. The Soviet official response was apparently to reject these attempts and reportedly "refused to consider any reduction in Hess's life sentence." U.S. President Richard Nixon was in favor of releasing Hess and stated that the U.S., Britain and France should continue to entreat the Soviet Union for his release.

In 1977, Britain's chief prosecutor at Nuremberg, Sir Hartley Shawcross, characterized Hess's continued imprisonment as a "scandal". In 1987, the new Soviet leadership agreed that Hess should be set free on humanitarian grounds.

The restrictions of communication in prison for Hess were harsh. Family visits were restricted to a half - hour visit once a month; he considered this degrading and refused such short visits until 1968. In the 1970s he was visited by members of his family once a month, and later in the 1970s on "humanitarian grounds" visitation rights were extended to one hour per month. Hess was never allowed to discuss anything related to the period of World War II or to the Nazi regime.

Hess's letters and all communication were subject to censorship. British government files released by The National Archives detail a disagreement between the western powers and the Soviet Union regarding rights, especially censorship. The Soviet governor argued that uncensored letters to Hess's wife could be used to construct a propagandist essay.

British

government files opened on 28 September 2007 by The National Archives

from the period 6 May to 6 August 1974 contains a report of an

altercation between Hess and a Soviet warder. The western governors

raise issues of Soviet policy towards Hess, for example taking away

Hess’s glasses before lights out, destroying his notebooks, increasing

the strictness of censorship and blocking visits by Hess’s lawyer.

On 17 August 1987, Hess died while under Four - Power imprisonment at Spandau Prison in West Berlin, at the age of 93. He was found in a summer house in a garden located in a secure area of the prison with an electrical cord wrapped around his neck. His death was ruled a suicide by asphyxiation. He was buried at Wunsiedel in a Hess family grave plot sold to his family by the Vetters of the Sechsämtertropfen bitter liquor company of Wunsiedel. Spandau Prison was subsequently demolished to prevent it from becoming a shrine.

Hess was the last surviving member of Hitler's cabinet.

Neo - Nazis from Germany and Europe held gatherings in Wunsiedel for a memorial march and similar demonstrations that took place every year around the anniversary of Hess's death. These gatherings were banned from 1991 to 2000 and neo - Nazis tried to assemble in other cities and countries (such as the Netherlands and Denmark). Demonstrations in Wunsiedel were again legalized in 2001. After stricter German legislation regarding demonstrations by neo - Nazis was enacted in March 2005, the demonstrations were banned again.

With the grave's lease due to expire in October 2011, the Hess family applied for a 20 year extension which was denied. "We decided not to extend the lease because of all the unrest and disturbances," said parish council chairman Peter Seisser. After negotiations between the church's chaplin and Hess's granddaughter, the family agreed to remove his remains from the town. Hess's grave was re-opened on the morning of 20 July 2011 and his remains exhumed then cremated. Soon afterward his ashes were scattered at sea; the gravestone, which bore the epitaph "Ich hab's gewagt" ("I dared"), was destroyed.

Hess ordered a mapping of all the ley lines in the Third Reich. There is speculation that Hess was questioned by the British about Nazi interest in the occult.

There have been conspiracy theories concerning his death, mainly from Wolf Rüdiger Hess.

Wolfgang Spann, who was in charge of the second autopsy, publicly stated that "we can't prove a third hand participated in the death of Rudolf Hess".

In 2008 Abdallah Melaouhi, a Tunisian who acted as Hess's medical caretaker in Spandau prison from 1984 to 1987, was dismissed from his position in his local German district parliament's advisory board for integration after he wrote a book, I Looked into the Murderer's Eyes. He had claimed in the book that his patient was murdered by MI6 (the British Secret Intelligence Service).

According to Hugh Thomas's book The Murder of Rudolf Hess (1979), the prisoner tried at Nuremberg and incarcerated in Spandau as Rudolf Hess was actually an imposter. Dutch author At Voorhorst contradicts Thomas's allegations with his study in which he compares biometric features of the prisoner in Spandau prison and deputy of Hitler in the Second World War.