<Back to Index>

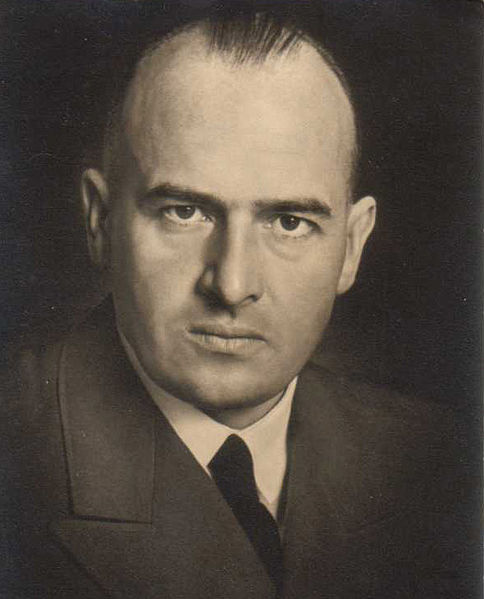

- Chief of the Party Chancellery Martin Ludwig Bormann, 1900

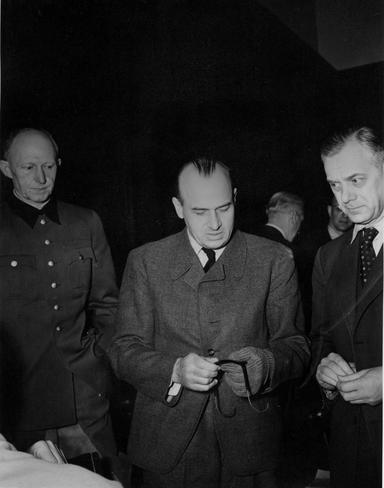

- Governor General of the General Government Hans Michael Frank, 1900

PAGE SPONSOR

Martin Ludwig Bormann (17 June 1900 – 2 May 1945?) was a prominent Nazi official. He became head of the Party Chancellery (Parteikanzlei) and private secretary to Adolf Hitler. He gained Hitler's trust and derived immense power within the Third Reich by controlling access to the Führer and by regulating the orbits of those closest to him.

Born in Wegeleben (now in Saxony - Anhalt) in the Kingdom of Prussia in the German Empire, Bormann was born to a Lutheran family, the son of Theodor Bormann (1862 – 1903), a post office employee, and his second wife, Antonie Bernhardine Mennong. He had two half siblings (Else and Walter Bormann) from his father's earlier marriage to Louise Grobler, who died in 1898. Antonie Bormann gave birth to three sons, one of whom died in infancy. Martin (born 1900) and Albert (born 1902) survived to adulthood.

Bormann dropped out of school to work on a farm in Mecklenburg. He served in an artillery regiment in the last days of World War I, but never saw action. He then became an estate manager in Mecklenburg, which brought him into contact with the Freikorps residing on the estate. He took part in their activities, mostly in assassinations and the intimidation of trade union organizers.

On 17 March 1924, Bormann was sentenced to a year in prison as an accomplice to his friend Rudolf Höss in the murder of Walther Kadow, who they thought had betrayed Freikorps Albert Leo Schlageter to the French during the occupation of the Ruhr District.

On 2 September 1929, Bormann married 19 year old Gerda Buch, whose father, Major Walter Buch, served as a chairman of the Nazi Party Court. Bormann had recently met Hitler, who agreed to serve as a witness at their wedding. Gerda Bormann would give birth to 10 children; one died shortly after birth.

The children of Martin and Gerda Bormann were:

- Adolf Martin Bormann (born 14 April 1930; called Krönzi; named after his godfather Adolf Hitler)

- Ilse Bormann (born 9 July 1931; twin sister Ehrengard died after the birth; named after her godmother Ilse Hess, later called "Eike", died 1958)

- Irmgard Bormann (born 25 July 1933)

- Rudolf Gerhard Bormann (born 31 August 1934; named after his godfather Rudolf Hess)

- Heinrich Hugo Bormann (born 13 June 1936; named after his godfather Heinrich Himmler)

- Eva Ute Bormann (born 4 August 1938)

- Gerda Bormann (born 23 October 1940)

- Fred Hartmut Bormann (born 4 March 1942)

- Volker Bormann (born 18 September 1943, died 1946)

Gerda Bormann suffered from cancer in her later years, and died of mercury poisoning on 23 March 1946, in Merano, Italy. All of Bormann's children survived the war. Most were cared for anonymously in foster homes. His eldest son, Martin, was Hitler's godson. Martin abandoned the Lutheran faith of his family and was ordained a Roman Catholic priest in 1953, but left the priesthood in the late 1960s. He married an ex-nun in 1971 and became a teacher of theology.

In 1927, Bormann joined the NSDAP. His NSDAP number was 60,508 and his (honorary) SS membership number was originally 278,267. By special order of Himmler in 1938, Bormann was granted SS number 555 to reflect his Alter Kämpfer (Old Fighter) status. He became the party's regional press officer and business manager in 1928.

On 10 October 1933, Bormann became a Reich Leader (Reichsleiter) of the NSDAP, and in November, a member of the Reichstag. From 1 July 1933 until 1941, Bormann served as the personal secretary for Rudolf Hess. Bormann commissioned the building of the Kehlsteinhaus (Eagle's Nest). The Kehlsteinhaus was formally presented to Hitler on 20 April 20 1938, after 13 months of expensive construction, and is commemorated on a plaque just above the entrance to the tunnel to the lift up to the Eagle's Nest. During this period, Bormann had also managed Hitler's finances through various schemes such as royalties collected on Hitler's book, his image on postage stamps, as well as setting up an "Adolf Hitler Endowment Fund of German Industry", which was really a thinly veiled extortion attempt on the behalf of Hitler to collect more money from German industrialists.

In May 1941, the flight of Hess to Britain cleared the way for Bormann to become Head of the Party Chancellery (Parteikanzlei) that same month. Bormann proved to be a master of intricate political infighting. Due to his mastery of such infighting, along with his access and closeness to Hitler, and because of the trust Hitler held in him, he was able to constantly and effectively check and thus make enemies of Joseph Goebbels, Hermann Göring, Heinrich Himmler, Alfred Rosenberg, Robert Ley, Albert Speer and a plethora of other high ranking officers and officials, both public and private. The ruthless and continuous intriguing for power, influence, and favor from Hitler within the regime came to characterize the inner workings of the Third Reich.

Bormann took charge of all of Hitler's paperwork, appointments and personal finances. Hitler came to have complete trust in Bormann and the view of reality he presented. During one meeting, Hitler was said to have screamed, "To win this war, I need Bormann!" Some historians have suggested Bormann held so much power that, in some respects by 1945, he became Germany's "secret leader" during the war. A collection of transcripts edited by Bormann during the war appeared in print in 1952 and 1953 as Hitler's Table Talk1941 – 1944, mostly a re-telling of Hitler's wartime dinner conversations.

Bormann's bureaucratic power and effective reach had broadened considerably by 1942. Later, faced with the imminent demise of the Third Reich, he systematically set about organizing German corporate flight capital, and established off shore holding companies and business interests in close coordination with the same Ruhr industrialists and German bankers who, although often not Nazis, had helped to facilitate Hitler's explosive rise to power 10 years before.

His view of Christianity was epitomized in a confidential memo to the Gauleiters in 1942 by stating that Nazism "was completely incompatible with Christianity". Contrary to Hitler's tactical judgment, Bormann pushed the Kirchenkampf forward at the height of World War II. He reopened the fight against the Christian churches, declaring in a confidential memo to the Gauleiters in 1942 that their power 'must absolutely and finally be broken.' Bormann viewed the power of the churches and Christianity to be completely incompatible with Nazism, and saw their influence as a serious obstacle to totalitarian rule. The sharpest anti - cleric in the Nazi leadership (he collected all the files of cases against the clergy that he could lay his hands on), Bormann was the driving force of the Kirchenkampf, which Hitler for tactical reasons had wished to postpone until after the war.

In February 1943, the German defeat at the Battle of Stalingrad produced a crisis in the regime. Bormann exploited the disaster at Stalingrad, and his daily access to Hitler, to persuade him to create a three man junta representing the State, the Army and the Party, represented respectively by Hans Lammers, head of the Reich Chancellery, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, chief of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht ("Armed Forces High Command", or OKW), and Bormann, who controlled the Party and access to the Führer. This Committee of Three would exercise dictatorial powers over the home front. Goebbels, Speer, Göring and Himmler all saw this proposal as a power grab by Bormann and a threat to their power, and combined to block it.

However, their alliance was shaky at best. This was mainly due to the fact that during this period Himmler was still cooperating with Bormann to gain more power at the expense of Göring and most of the traditional Reich administration. Göring's loss of power had resulted from an overindulgence in the trappings of power and his strained relations with Goebbels made it difficult for a unified coalition to be formed, despite the attempts of Speer and Göring's Luftwaffe deputy Field Marshal Erhard Milch, to reconcile the two Party comrades.

However, the result was that nothing was done — the Committee of Three declined into irrelevance due to the loss of power by Keitel and Lammers and the ascension of Bormann, and the situation continued to drift, with administrative chaos increasingly undermining the war effort. The ultimate responsibility for this lay with Hitler, as Goebbels well knew, referring in his diary to a "crisis of leadership," but Goebbels was too much under Hitler’s spell ever to challenge his power.

Bormann was invariably the advocate of extremely harsh, radical measures when it came to the treatment of Jews, of the conquered eastern peoples or prisoners of war. He signed the decree of 9 October 1942 prescribing that "the permanent elimination of the Jews from the territories of Greater Germany can no longer be carried out by emigration but by the use of ruthless force in the special camps of the East." A further decree, signed by Bormann on 1 July 1943, gave Adolf Eichmann absolute powers over Jews, who now came under the exclusive jurisdiction of the Gestapo.

Bormann's memos concerning the Slavs make it clear that he regarded them as a 'Sovietized mass' of sub - humans who had no claim to national independence. In a brutal memo of 19 August 1942, he wrote: "The Slavs are to work for us. In so far as we do not need them, they may die. Slav fertility is not desirable."

At the Nuremberg Trials, Arthur Seyss - Inquart, the Reich Commissioner for the Netherlands, testified that he had called Bormann to confirm an order to deport the Dutch Jews to Auschwitz, and further testified that Bormann passed along Hitler's orders for the extermination of Jews during the Holocaust. A telephone conversation between Bormann and Heinrich Himmler,

who was his main antagonist in the struggle for power within the Nazi

elite, was overheard by telephone operators during which Himmler

reported to Bormann the extermination of 40,000 Jews in Poland. Himmler

was sharply rebuked for using the word "exterminated" rather than the

codeword "resettled," and Bormann ordered the apologetic Himmler never

again to report on this by phone but through SS couriers.

Bormann, his adjutant, SS - Standartenführer Wilhelm Zander, and his secretary, Else Krüger, were with Hitler in the Führer's shelter (Führerbunker) during the Battle of Berlin. The Führerbunker was located under the Reich Chancellery (Reichskanzlei) gardens in the center government district of Berlin. On 23 April, his brother Albert Bormann left the Berlin bunker complex by aircraft for the Obersalzberg. He and several others had been ordered by Hitler to leave Berlin.

On 28 April, Bormann wired the following message to Großadmiral Karl Dönitz: "Situation very serious . . . Those ordered to rescue the Führer are keeping silent . . . Disloyalty seems to gain the upper hand everywhere . . . Reichskanzlei a heap of rubble."

At 04:00 on 29 April 1945, Wilhelm Burgdorf, Joseph Goebbels, Hans Krebs, and Bormann witnessed and signed Hitler's last will and testament. Hitler dictated this document to his personal secretary, Traudl Junge. Bormann was Head of the Party Chancellery (Parteikanzlei) and was also the private secretary to Hitler. Shortly before signing the last will and testament, Hitler married Eva Braun in a civil ceremony.

The Soviet forces continued to fight their way into the center of Berlin. Adolf and Eva Hitler committed suicide during the afternoon of the 30 April. Eva took cyanide and Adolf Hitler shot himself. As per instructions, their bodies were taken to the garden and burned. In accordance with Hitler's last will and testament, Joseph Goebbels, the Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, became the new "Head of Government" and Chancellor of Germany (Reichskanzler). Martin Bormann was named as Party Minister, thus officially confirming his position as de facto General Secretary of the Party.

At 03:15 on 1 May, Reichskanzler Goebbels and Bormann sent a radio message to Dönitz informing him of Hitler's death. In accordance with Hitler's last wishes, Dönitz was appointed as the new "President of Germany" (Reichspräsident). Goebbels and his wife committed suicide later that same day.

On 2 May, the Battle in Berlin ended when General der Artillerie Helmuth Weidling, the commander of the Berlin Defense Area, unconditionally surrendered the city to General Vasily Chuikov, the commander of the Soviet 8th Guards Army. It is agreed that, by this day, Bormann had left the Führerbunker. It has been reported that he left with Ludwig Stumpfegger and Artur Axmann as part of a group attempting to break out of the Soviet encirclement of the city.

As World War II came to a close, Bormann held out with Hitler in the Führerbunker in Berlin. On 30 April 1945, just before committing suicide, Hitler signed the order to allow a breakout. On 1 May, Bormann left the Führerbunker with SS doctor Ludwig Stumpfegger, Hitler Youth leader Artur Axmann and Hitler's pilot Hans Baur as part of one of the groups attempting to break out of the Soviet encirclement. At the Weidendammer Bridge, a Tiger tank spearheaded the first attempt to storm across the bridge, but it was destroyed. Bormann and Stumpfegger were "knocked over" when the tank was hit. There followed two more attempts and on the third attempt, made around 1:00, Bormann in his group from the Reich Chancellery crossed the Spree. Leaving the rest of their group, Bormann, Stumpfegger and Axmann walked along railway tracks to Lehrter station, where Axmann decided to go alone in the opposite direction of his two companions. When he encountered a Red Army patrol, Axmann doubled back and later insisted he had seen the bodies of Bormann and Stumpfegger near the railway switching yard with moonlight clearly illuminating their faces. He did not check the bodies, so he did not know what killed them.

Axmann, Werner Naumann, and their adjutants escaped Berlin. Axmann hid in the Bavarian Alps under the alias "Erich Siewert". He was arrested in December 1945 while organizing an underground Nazi movement. Naumann found asylum in Argentina, where he became an editor of the neo - Nazi magazine Der Weg.

Lieutenant

General Konstantin Telegin, of the Soviet 5th Shock Army, remembered

his men bringing Bormann’s diary to him. "It was brought in immediately

after the fighting had ended. As far as I can remember, it was found on

the road when they were cleaning up the battle area." Inspired by the

diary and reports from prisoners, Telegin said, "Naturally, we sent a

recon group to the bridge, who searched the site of the breakthrough

attempt. All they found were a few civilians. Bormann was not found."

During the chaotic closing days of the war, there were contradictory reports as to Bormann's whereabouts. For example, Jakob Glas, Bormann's long time chauffeur, insisted he saw Bormann in Munich weeks after 1 May 1945. The bodies were not found, and a global search followed including extensive efforts in South America. With no evidence sufficient to confirm Bormann's death, the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg tried Bormann in absentia in October 1946 and sentenced him to death. His court appointed defense lawyer used the unusual and unsuccessful defense that the court could not convict Bormann because he was already dead.

In 1965, a retired postal worker named Albert Krumnow stated that around 8 May 1945 the Soviets had ordered him and his colleagues to bury two bodies found near the railway bridge near Lehrter station. One was "a member of the Wehrmacht" and the other was "an SS doctor".

Krumnow’s colleague, Wagenpfohl is said to have found a paybook on the SS doctor’s body identifying him as Dr. Ludwig Stumpfegger. He gave the paybook to his boss, postal chief Berndt, who turned it over to the Soviets. They in turn destroyed it. The Soviets allowed Berndt to notify Stumpfegger’s wife. He wrote and told her that her husband’s body was "…interred with the bodies of several other dead soldiers in the grounds of the Alpendorf in Berlin NW 40, Invalidenstrasse 63."

In mid 1965, Berlin police excavated the alleged burial site looking for Bormann's remains, but found nothing. Krumnow stated he could no longer remember exactly where he buried the bodies. Stern magazine editor Jochen Von Lang, whose investigation inspired the dig, later wrote, "even if bones had been discovered, it would have been exceedingly difficult to identify them as those of Martin Bormann." He went on to opine that the only way to identify Bormann would be to find "glass particles" from a cyanide capsule in the jaw and that "would border almost on the miraculous."

Unconfirmed sightings of Bormann were reported globally for 20 years, particularly in Europe, Paraguay and elsewhere in South America. Some rumors claimed that Bormann had plastic surgery while on the run. At a 1967 press conference, Simon Wiesenthal asserted there was strong evidence that Bormann was alive and well in South America. Writer Ladislas Farago's widely known 1974 book Aftermath: Martin Bormann and the Fourth Reich argued that Bormann had survived the war and lived in Argentina. Farago's evidence, which drew heavily on official governmental documents, was compelling enough to persuade Dr. Robert M.W. Kempner (a lawyer at the Nuremberg Trials) to briefly re-open an active investigation in 1972. However, Farago's claims were generally rejected by historians and critics. Allegations that Bormann and his organization survived the war figure prominently in the work of David Emory. More recently, researchers Simon Dunstan and Gerrard Williams have also stated in their recent work that Bormann escaped to South America and spent the years prior to 1945 preparing the escape plan.

Reinhard Gehlen states in his memoirs his

conviction that Bormann was a Russian agent and that at the time of his

'disappearance' in Berlin he in reality went over to his Russian

masters and was spirited away by them to Moscow. He bases his conclusion

on a conversation he had with Admiral Canaris and

on his conviction that there was an enemy agent at work inside the

German supreme command. He deduced the latter from the fact that the

Russians appeared to be able to obtain "rapid and detailed information

on incidents and top level decision making on the German side". Of

course, at the time he was writing up his memoirs (late 1960s to early

1970s), Gehlen was not aware of the breaking of the Enigma codes. Gehlen goes on to say that he discovered that Bormann was engaged in a Funkspiel with Moscow with Hitler's express approval. He claims that in the 1950s, when he headed first the Gehlen Organization and later the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND), the West German Intelligence Service, he "was passed two separate reports from behind the Iron Curtain to the effect that Bormann had been a Soviet agent and had lived after the war in the Soviet Union under

perfect cover as an adviser to the Moscow government. He has died in

the meantime." (1971 ed.) After the collapse of the

Soviet Union, based on KGB archival

material from this period, it was claimed that the Russians may indeed

have had a spy in the bunker, code named Sasha. However, Sasha was said

to have been a Russian, not Bormann.

The hunt for Bormann lasted 26 years without success. International investigators and journalists searched for Bormann from Paraguay to Moscow and from Norway to Egypt. Digs for his body in Paraguay in March 1964 and Berlin in July 1964 were unsuccessful. The German government offered a 100,000 Mark reward in November 1964, but no one claimed it. The final straw came in July 1965, when the search of Albert Krumnow’s Berlin location turned up nothing. The German government determined that Berlin was simply "too full of cemeteries and mass graves dating from the last days of the war."

On the political end, the hunt for Bormann became a recurring memory of the Nazi regime and also an embarrassment that would not go away. On 13 December 1971, the West German government officially called an end to the search for Bormann. This pronouncement was met with protest from Jewish human rights groups and Nazi hunters like Simon Wiesenthal who insisted the search must continue until Bormann was found, alive or dead.

Almost a year later, on 7 December 1972, Axmann and Krumnow's accounts were bolstered when construction workers uncovered human remains near the Lehrter Bahnhof in West Berlin just 12 m (39 ft) from the spot where Krumnow claimed he had buried them. Dental records — reconstructed from memory in 1945 by Dr. Hugo Blaschke — identified the skeleton as Bormann's, and damage to the collarbone was consistent with injuries Bormann's sons reported he had sustained in a riding accident in 1939. The second skeleton was deemed to be Stumpfegger‘s, since it was of similar height to his last known proportions. Fragments of glass in the jawbones of both skeletons suggested that Bormann and Stumpfegger committed suicide by biting cyanide capsules to avoid capture. Soon after, in a press conference held by the West German government, Bormann was declared dead, a statement condemned by Britain's Daily Express as a whitewash perpetrated by the Brandt government. West German diplomatic officials were given official instruction that "if anyone is arrested on suspicion that he is Bormann we will be dealing with an innocent man".

The remains were conclusively identified as Bormann's in 1998 when German authorities ordered a genetic test on the skull. The test identified the skull as that of Bormann, using DNA from one of his relatives. Bormann's remains were cremated and the ashes scattered in the Baltic Sea by Bormann's son Martin Adolf Bormann, a Roman Catholic and retired priest.

Despite these DNA tests, there had and continues to be controversy regarding the authenticity of the remains. For example, Hugh Thomas' 1995 book Doppelgängers claimed there were forensic inconsistencies suggesting Bormann died later than 1945. When exhumed, Bormann’s skeleton was covered in flecks of red clay, whereas Berlin is a city based on yellow sand. This indicated to some that the body had been re-interred from somewhere with a clay based soil, such as Paraguay, the Andes Mountains or even Russia (as the Gehlen theory surmised).

Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal refused to accept the government’s declaration of Bormann‘s death, persisting in the belief that Bormann escaped Berlin with Axmann and headed south to the safety of the Alps. There he was rumored to have been seen in both Bavaria and Austria. Bormann’s aide Wilhelm Zander was captured in Passau, along the Austrian frontier, in December 1945. From the Alps, Wiesenthal believed, Bormann and others escaped to South America.

Others, like English scholar and intelligence officer Hugh Trevor - Roper,

decried the evidence upon which the German government based its

searches for Bormann: the testimony of one man. He and others argued

that the testimony of Artur Axmann, the only man who said he saw Bormann

dead was falsified to protect Bormann who was then on the run. Both men

were unrepentant Nazis and shared the motivation to keep their cause

alive. Axmann, they argued, probably escaped Berlin with Bormann.

Russian author Lev Bezymenski wrote that Axmann’s statements had, "the

apparent aim of convincing the world that the Reichsleiter had

been killed." Bezymenski also wrote that Axmann’s statements, "give

rise to a lot of doubt, especially when one considers that he changed

his explanations at least three times in the postwar years." Some

also believed it implausible that the Soviets would identify the body

of Stumpfegger and ignore Bormann’s body, supposedly at Stumpfegger’s

side. Further, it was said that Bormann was reinterred only to later be

"discovered" by the German government.

Hans Michael Frank (23 May 1900 – 16 October 1946) was a German lawyer who worked for the Nazi party during the 1920s and 1930s, and after Hitler's accession to power in 1933, became chief jurist of Nazi Germany and Governor General of the 'General Government' territory of occupied Poland. During his tenure (1939 – 1945), he instituted a reign of terror against the civilian population and became directly involved in the mass murder of the Polish Jews. At the Nuremberg trials, he was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity and executed.

Frank was born in Karlsruhe, and his parents were Karl Frank, a lawyer, and his wife Magdalena (née Buchmaier). He had an older brother, Karl Jr., and a younger sister, Elisabeth. He joined the German army in 1917, during World War I. After the war he served in the Freikorps under the command of Franz Ritter von Epp, and then joined the German Worker's Party (which soon evolved into NSDAP), in 1919, and was one of the party's earliest members.

He studied law, passing the final state examination in 1926, and rose to become Adolf Hitler's personal legal adviser. In this capacity, Frank was privy to personal details of Hitler's life. In his memoirs, written shortly before his execution, Frank made the sensational claim that he had been commissioned by Hitler to investigate Hitler's family in 1930 after a "blackmail letter" had been received from Hitler's nephew, William Patrick Hitler, who allegedly threatened to reveal embarrassing facts about his uncle's ancestry. Frank said that the investigation uncovered evidence that Maria Schicklgruber, Hitler's paternal grandmother, had been working as a cook in the household of a Jewish man named Leopold Frankenberger before she gave birth to Hitler's father, Alois, out of wedlock. Frank claimed that he had obtained from a relative of Hitler's by marriage a collection of letters between Maria Schicklgruber and a member of the Frankenberger family that discussed a stipend for her after she left the employ of the family. According to Frank, Hitler told him that the letters did not prove that the Frankenberger son was his grandfather but rather his grandmother had merely extorted money from Frankenberger by threatening to claim his paternity of her illegitimate child. Frank accepted this explanation, but added that it was still just possible that Hitler had some Jewish ancestry. Nevertheless, he thought it unlikely because, "...from his entire demeanor, the fact that Adolf Hitler had no Jewish blood coursing through his veins seems so clearly evident that nothing more need be said on this."

Given that all Jews had been expelled from the province of Styria (which includes Graz) in the 15th century and were not allowed to return until the 1860s, scholars such as Ian Kershaw and Brigitte Hamann dismiss the Frankenberger hypothesis, which before had only Frank's speculation to support it as baseless. There is no evidence outside of Frank's statements for the existence of a "Leopold Frankenberger" living in Graz in the 1830s, and Frank's story is notably inaccurate on several points such as the claim that Maria Schicklgruber came from "Leonding near Linz", when in fact she came from the hamlet of Strones near the village of Döllersheim. It has been suggested that Frank, who turned against National Socialism after 1945, remained an anti - Semitic fanatic, made the claim that Hitler had Jewish ancestry as way of proving that Hitler was thus really a "Jew" and not an "Aryan"; and in this way, "proved" that the crimes of the Third Reich were the work of the "Jewish" Hitler. The full anti - Semitic implications of Frank's story were borne out in a letter to the editor of a Saudi newspaper in 1982 by a German man living in Saudi Arabia entitled "Was Hitler a Jew?". The letter writer accepted Frank's story as the truth, and added since Hitler was a Jew, "the Jews should pay Germans reparations for the War, since one of theirs caused the destruction of Germany". The American author Ron Rosenbaum wrote about Frank:

"On the other hand, a different version of Frank emerges in the brilliantly vicious, utterly unforgiving portrait of him by his son, Niklas Frank, who (in a memoir called In the Shadow of the Reich) depicts his father as a craven coward and weakling, but one not without a kind of animal cunning, an instinct for lying, insinuation, self - aggrandizement. For this Hans Frank, disgraced and facing death on the gallows for following Hitler, fabricating such a story might be a cunning way of ensuring his place in history as the one man who gave the world the hidden key to the mystery of Hitler's psyche. While at the same time, revenging himself on his former master for having led him to this end by foisting a sordid and humiliating explanation of Hitler on him for all posterity. In any case, it was one Frank knew the victors would find seductive".

As the Nazis rose to power, Frank served as the party's lawyer, representing it in over 2,400 cases, and spending over $10,000. This sometimes brought him into conflict with other lawyers, and one, a former teacher of Frank's appealed to him: "I beg you to leave these people alone! No good will come of it! Political movements that begin in the criminal courts will end in the criminal courts!" In September – October 1930, Frank served as the defense lawyer at the court martial in Leipzig of Lieutenants Richard Scheringer, Hans Friedrich Wendt and Hanns Ludin, three Reichswehr officers charged with membership in the NSDAP. The trial was a media sensation with Hitler himself testifying, and the defense successfully putting the Weimar Republic on trial, and many Army officers won over to a sympathetic view of the National Socialist movement.

Frank was elected to the Reichstag in 1930, and in 1933 he was made Minister of Justice for Bavaria. From 1933, he was also the head of the National Socialist Jurists Association and President of the Academy of German Law. Frank objected to extrajudicial killings, both at the Dachau concentration camp and during the Night of the Long Knives.

Frank's view of what the judicial process required should not be exaggerated:

| “ | [The judge's] role is to safeguard the concrete order of the racial community, to eliminate dangerous elements, to prosecute all acts harmful to the community, and to arbitrate in disagreements between members of the community. The National Socialist ideology, especially as expressed in the Party program and in the speeches of our Leader, is the basis for interpreting legal sources. | ” |

From 1934, Frank was Reich Minister Without Portfolio.

In September 1939 Frank was assigned as Chief of Administration to Gerd von Rundstedt in the German military administration in occupied Poland. From 26 October 1939, following the end of the invasion of Poland, Frank was assigned Governor General of the occupied Polish territories (Generalgouverneur für die besetzten polnischen Gebiete), controlling the General Government, the area of Poland not directly incorporated into Germany (roughly 90,000 km² out of the 187,000 km² Germany had gained). He was also granted the SS rank of Obergruppenführer.

One of his first operations was the AB Action, aimed at destroying Polish culture, and in which more than 30,000 Poles (intellectuals and the upper classes) were arrested and 7,000 were subsequently massacred. Frank oversaw the segregation of the Jews into ghettos and the use of Polish civilians as "forced and compulsory" labor. In 1942 he lost his positions of authority outside the GG after annoying Hitler with a series of speeches in Berlin, Vienna, Heidelberg and Munich and also as part of a power struggle with Friedrich Wilhelm Krüger, the State Secretary for Security — head of the SS and the police in the GG. Krüger himself was ultimately replaced with Wilhelm Koppe.

An assassination attempt by Polish Secret State on 29 / 30 January 1944 (the night preceding the 11th anniversary of the appointment of Adolf Hitler as Chancellor of Germany) in Szarów near Krakow failed. A special train with Frank traveling to Lviv was derailed after an explosive device went off but no one was killed.

As governor general, Frank "stripped away" his appearance of culture stating to his cabinet,

| “ | Gentlemen, I must ask you to rid yourself of pity. We must annihilate the Jews. | ” |

The General Government was the location of four of the six extermination camps. Frank later claimed that the extermination of Jews was entirely controlled by Heinrich Himmler and the SS and that he, Frank, was unaware of the extermination camps in the GG until early in 1944. During his testimony at Nuremberg, Frank claimed he submitted resignation requests to Hitler on 14 occasions, but Hitler would not allow him to resign. Frank fled GG in January 1945, in advance of the Soviet Army.

Hans Frank was extremely interested in chess.

He not only possessed an extensive library of chess literature but was

also a good player, and he even received the Ukrainian chess grandmaster Efim Bogoljubow at the Wawel castle. He was a patron of General Government chess tournaments (1940 – 1944). On 3 November 1940 he organized a chess congress in Krakow. Six months later he announced the establishment of a chess school under Bogoljubow and the World Chess Champion, Dr. Alexander Alekhine, and he visited a chess tournament in October 1942 at the "Literary Café" in Krakow.

Frank was captured by American troops on 3 May 1945, at Tegernsee in southern Bavaria. Upon his capture, he tried to cut his own throat; two days later, he lacerated his left arm while attempting to slit his wrists in a second unsuccessful suicide attempt. He was indicted for war crimes and tried before the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg from 20 November 1945 to 1 October 1946. During the trial he renewed the faith of his childhood, Roman Catholicism, and claimed to have a series of religious experiences.

Frank voluntarily surrendered 43 volumes of his personal diaries to the Allies, which were then used against him as evidence of his guilt. Frank confessed to some of the charges put against him and viewed his own execution as a form of atonement for his sins.

Although on the witness stand he expressed remorse, during the trial,

he vacillated between penitence for his crimes and blaming the Allies,

especially the Soviets, for an equal share of wartime atrocities.

The former Governor General of Poland was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity on 1 October 1946, and was sentenced to death by hanging. While awaiting execution, he wrote his memoirs. The sentence was carried out on 16 October by Master Sergeant John C. Woods. Journalist Howard K. Smith wrote of the execution:

| “ | Hans Frank was next in the parade of death. He was the only one of the condemned to enter the chamber with a smile on his countenance. And, although nervous and swallowing frequently, this man, who was converted to Roman Catholicism after his arrest, gave the appearance of being relieved at the prospect of atoning for his evil deeds. | ” |

He and Albert Speer were allegedly the only defendants to show remorse for their war crimes. "My conscience does

not allow me simply to throw the responsibility simply on minor

people... A thousand years will pass and still Germany's guilt will not

have been erased." He

answered to his name quietly and when asked for any last statement, he

replied "I am thankful for the kind treatment during my captivity and I

ask God to accept me with mercy."

On 2 April 1925 Frank married 29 year old secretary Brigitte Herbst (1895 – 1959) from Forst (Lausitz). The wedding took place in Munich and the couple honeymooned in Venetia. Hans and Brigitte Frank had five children:

- Sigrid Frank (born 13 March 1927, Munich)

- Norman Frank (born 3 June 1928, Munich)

- Brigitte Frank (born 13 January 1935, Munich)

- Michael Frank (born 15 February 1937, Munich)

- Niklas Frank (born 9 March 1939, Munich)

Brigitte Frank had a reputation for having a more dominant personality than her husband, and from 1939 she called herself "a queen of Poland" ("Königin von Polen"). The marriage was unhappy and became colder from year to year. When Frank sought a divorce in 1942, Brigitte gave everything to save their marriage in order to remain the "First Lady in the General Government". One of her most famous comments was "I'd rather be widowed than divorced from a Reichsminister!" Frank answered: "So you are my deadly enemy!"

In 1987, Niklas Frank wrote a book about his father, Der Vater: Eine Abrechnung ("The Father: A Settling of Accounts"), which was published in English in 1991 as In the Shadow of the Reich. The book, which was serialized in the magazine Stern,

resulted in controversy in Germany because of the scathing way in which

the younger Frank depicted his father, referring to him as "a

slime - hole of a Hitler fanatic" and questioning his remorse before his

execution.

In a 1940 interview in the Völkischer Beobachter:

| “ | In Prague, big red posters were put up on which one could read that seven Czechs had been shot today. I said to myself, 'If I had to put up a poster for every seven Poles shot, the forests of Poland would not be sufficient to manufacture the paper.' | ” |

About Polish partisans in Warsaw in 1943, he spoke from Kraków, stating:

| “ | If not for Warsaw in the General Government, we wouldn't have 4/5 of our current problems on that territory. Warsaw was and will be the center of chaos and a place from which opposition spreads throughout the rest of the country. | ” |

| “ | A thousand years will pass and still Germany's guilt will not have been erased. | ” |

| “ | There is still one statement of mine which I must rectify. On the witness stand I said that a thousand years would not suffice to erase the guilt brought upon our people because of Hitler's conduct in this war. Every possible guilt incurred by our nation has already been, completely wiped out today, not only by the conduct of our war - time enemies towards our nation and its soldiers, which has been carefully kept out of this Trial, but also by the tremendous mass crimes of the most frightful sort which - as I have now learned - have been and still are being committed against Germans by Russians, Poles, and Czechs, especially in East Prussia, Silesia, Pomerania, and Sudetenland. Who shall ever judge these crimes against the German people?" | ” |