<Back to Index>

- President of the People's Court Roland Freisler, 1893

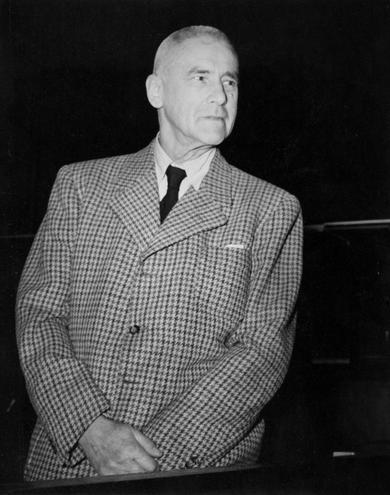

- Reich Minister of the Interior Wilhelm Frick 1877

PAGE SPONSOR

Roland Freisler (30 October 1893 – 3 February 1945) was a prominent and notorious Nazi lawyer and judge. He was State Secretary of the Reich Ministry of Justice and President of the People's Court (Volksgerichtshof), which was set up outside constitutional authority. This court handled political actions against Hitler's dictatorial regime by conducting a series of show trials.

In contrast to most of the Nazi leadership, not much beyond basic detail is known about Freisler. He was born in Celle, the son of an engineer, and saw active service during World War I. He was an officer cadet in 1914, and by 1915 he was a Lieutenant. He won a decoration. In October 1915, he was captured by Russian troops.

While a prisoner of war in Russia, Freisler learned Russian. He is said to have developed an interest in Marxism after the Russian Revolution; the Bolsheviks made use of him as a commissar for the camp's food supplies. It is also said that after the prisoner camps were dissolved in 1918, Freisler became a convinced Communist, though this is not supported by any contemporaneous documents. However, historian H.W. Koch states that after the Bolshevik Revolution, the POW camps in Russia were handed over to German administration, and the title of commissar was merely functional, not political, and that "Freisler was never a Communist, though in the early days of his NS career [...] he belonged to the NSDAP's left wing."

Freisler himself rejected all accusations that he had even tentatively approached the hated enemy, but he could never fully escape the stigma of being a bolshie.

He returned to Germany in 1920 to study law at the University of Jena, becoming a Doctor of Law in 1922. From 1924, he worked as a lawyer in Kassel. He was also elected a city councilor, as a member of the Völkisch-Sozialer Block (German, roughly "People's Social Block"), an extreme nationalist splinter party.

In 1928, he married Marion Russegger. Together, they had two sons, Harald and Roland.

Even though the Nazis declared themselves arch - enemies of Marxism, Freisler joined the Nazi Party in July 1925. He registered with the NSDAP as member number 9679. During this period, he served as defense counsel for members of the nascent Party who got into trouble with the law. He was also a delegate to the Prussian Landtag, or state legislature, and later he became a member of the Reichstag.

In 1927, the Gauleiter of Kurhessen, Karl Weinrich, characterized Freisler in the following manner:

Rhetorically Freisler is equal to our best speakers, if not superior. Particularly on the broad masses, he has influence, but thinking people mostly reject him. Party Comrade Freisler is only usable as a speaker. He is unsuitable for any leadership post, since he is an unreliable and moody person.

In February 1933, Freisler was appointed department head in the Prussian Ministry of Justice. He was Secretary of State in the Prussian Ministry of Justice in 1933 – 1934, and in the Reich Ministry of Justice from 1934 – 1942. He represented the latter at the Wannsee Conference (20 January 1942), where he stood in for Minister Franz Schlegelberger, as regarding the detailed plans of the Final Solution, the murder of all European Jews.

Freisler's mastery of legal texts, mental agility and overwhelming verbal force combined well with strict adherence to the party line and the corresponding ideology, so that he became the most feared judge and the personification of the Nazis' "blood justice". Despite his undisputed legal competence, he was never appointed to cabinet. According to Uwe Wesel, this can be attributed to two factors. Firstly, Roland Freisler was regarded as a lone fighter and had no influential patron.

Secondly, he was compromised by his brother Oswald's rise actions. Oswald Freisler, though also a Nazi, appeared as the defense counsel in politically significant trials which the Nazis sought to use for propaganda purposes. Oswald even wore his Nazi Party badge in court, which confused the Party's role in these trials. Propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels accordingly reproved Roland Freisler and reported the incident to Hitler, who, for his part, decreed the immediate exclusion of Oswald Freisler from the party.

According to Guido Knopp, however, Goebbels was the only Nazi leader well disposed towards Freisler. In 1941, at a round table discussion in the Führer's headquarters, Goebbels proposed Freisler to replace Reich Justice Minister Franz Gürtner, who had died. Allegedly, Hitler's dismissive retort was: "That old Bolshevik? No!" Uwe Wesel reports a similar remark by Hitler.

Freisler published an article on "Die rassebiologische Aufgabe bei der Neugestaltung des Jugendstrafrechts ("The racial - biological task involved in the reform of Juvenile Criminal Law"). Freisler argued that "racially foreign, racially degenerate, racially incurable or seriously defective juveniles" should be sent to juvenile centers or correctional education centers and be segregated from those who are "German and racially valuable."

He strongly supported rigid laws against Rassenschande ("race defilement", the Nazi term for sexual relations between "Aryans" and inferior races) as racial treason. In 1933, Freisler published a pamphlet that called for banning "mixed - blood" intercourse, regardless of the kind or proportion of "foreign blood" involved, which faced strong public criticism and, at the time, no support from Hitler. This led to conflict with his superior, Franz Gürtner.

In October 1939, Freisler introduced the concept of 'precocious juvenile criminal' in the "Juvenile Felons Decree". This decree "provided the legal basis for imposing the death penalty and penitentiary terms on juveniles for the first time in German legal history". In the period 1933 through 1945, the courts sentenced at least 72 German juveniles to death, among them 16 year old Helmuth Hübener, found guilty of high treason for distributing anti - war leaflets in 1942.

The "Decree against National Parasites" (September 1939) introduced the term perpetrator type, which was used in combination with another Nazi term, parasite, The

adoption of racial biological terminology portrayed juvenile

criminality as parasitic, implying the need for harsher sentences.

Freisler justified the new measures in the following manner: "In times

of war, breach of loyalty and baseness cannot find any leniency and must

be met with the full force of the law."

On 20 August 1942, Hitler promoted Otto Georg Thierack to Reich Justice Minister, replacing the retiring Schlegelberger, and named Freisler to succeed Thierack as president of the People's Court (Volksgerichtshof). This court, set up outside the frame of law, had jurisdiction over a rather broad array of "political offenses", including black marketeering, work slowdowns, and defeatism. These actions were viewed by Freisler's court as Wehrkraftzersetzung (undermining defensive capability) and were accordingly punished severely, the death penalty being meted out in numerous cases. The People's Court almost always sided with the prosecution, to the point that being brought before it was tantamount to a death sentence. Not surprisingly, it was viewed as a kangaroo court.

Freisler chaired the First Senate of the People's Court, and acted as judge, jury and prosecution embodied into one man. He also acted as court recorder; that way, he was responsible for the composition of the written grounds for the sentences that he wrote up in his own unique fashion, namely in accordance with his own notions of a "National Socialist criminal court".

The number of death sentences rose sharply under Freisler's stewardship. Approximately 90% of all proceedings ended with sentences of death or life imprisonment, the sentences frequently having been determined before the trial. Between 1942 and 1945, more than 5,000 death sentences were handed out, and of these, 2,600 through the court's First Senate, which Freisler headed. Thus, Freisler alone was responsible, in his three years on the court, for as many death sentences as all other senate sessions of the court together in the entire time the court existed, between 1934 and 1945.

Freisler was known for humiliating defendants and shouting at them. He was known to be an admirer of Andrei Vyshinsky, the chief prosecutor of the Soviet purge trials, and reportedly copied his demeanor. A number of the trials for defendants in the 20 July Plot before the People's Court were filmed and recorded. In the 1944 trial against Ulrich Wilhelm Graf Schwerin von Schwanenfeld,

for example, Freisler shouted so loudly that the technicians who were

filming the proceeding had major problems making the defendant's words

audible. Schwerin von Schwanenfeld, like many other defendants in the

plot, was sentenced to death by hanging. Among this and other show

trials, Freisler headed the 1943 proceedings against the members of the White Rose resistance group, and ordered many of its members to be executed by guillotine.

On 3 February 1945, Freisler was conducting a Saturday session of the People's Court, when American bombers attacked Berlin. Government and Nazi Party buildings were hit, including the Reich Chancellery, the Gestapo headquarters, the Party Chancellery, and the People's Court.

According to one report, Freisler hastily adjourned court and had ordered that day's prisoners to be taken to a shelter, but paused to gather that day's files. Freisler was killed when an almost direct hit on the building caused him to be struck down by a beam in his own courtroom. His body was reportedly found crushed beneath a fallen masonry column, clutching the files that he had tried to retrieve. Among those files was that of Fabian von Schlabrendorff, a 20 July Plot member who was on trial that day and was facing execution.

According to a different report, Freisler "was killed by a bomb fragment while trying to escape from his law court to the air - raid shelter", and he "bled to death on the pavement outside the People's Court at Bellevuestrasse 15 in Berlin." Fabian von Schlabrendorff was "standing near his judge when the latter met his end."

Freisler's death saved von Schlabrendorff, who after the war became a judge of the Constitutional Court of the Federal Republic of Germany (Bundesverfassungsgericht).

Yet another version of Freisler's death states that he was killed by a British bomb that came through the ceiling of his courtroom as he was trying two women, who survived the explosion.

A foreign correspondent reported, "Apparently nobody regretted his death." Luise Jodl, the widow of General Alfred Jodl, recounted more than 25 years later that she had been working at the Luetzow Hospital when Freisler's body was brought in, and that a worker commented, "It is God's verdict." According to Mrs. Jodl, "Not one person said a word in reply."

Freisler is interred in the plot of his wife's family at the Waldfriedhof Dahlem cemetery in Berlin. His name is not shown on the gravestone.

Freisler is the "fictional" character Judge Feisler in the 1947 Hans Fallada novel Every Man Dies Alone (Jeder stirbt für sich allein). In 1943 he tried and handed down death penalties to Otto and Elise Hampel, whose true story inspired Fallada's novel.

Freisler has been portrayed by screen actors at least five times: by Rainer Steffen in the 1984 German television movie Wannseekonferenz, by Brian Cox in the British 1996 television movie Witness Against Hitler, by Owen Teale in the 2001 BBC/HBO film Conspiracy, by André Hennicke in the 2005 film Sophie Scholl – The Final Days, and by Helmut Stauss in the 2008 film Valkyrie.

Wilhelm Frick (12 March 1877 – 16 October 1946) was a prominent German Nazi official serving as Minister of the Interior of the Third Reich. After the end of World War II, he was tried for war crimes at the Nuremberg Trials and executed. Besides Adolf Hitler himself, he and Lutz Graf Schwerin von Krosigk were the only members of the Third Reich's cabinet to serve continuously from Hitler's appointment as Chancellor until his death.

Frick was born in Alsenz, Bavaria, Germany, the last of four children of teacher Wilhelm Frick the elder and his wife Henriette (née Schmidt). He was educated in Kaiserslautern and studied jurisprudence at Heidelberg, graduating in 1901. He joined the Bavarian civil service in 1903, working as a lawyer at the police headquarters in Munich. He was made a Bezirksamtassessor in 1907 and rose to the position of Regierungsassessor by 1917.

In 1910, Frick married Elisabetha Emilie Nagel (1890 – 1978) in Pirmasens. They had two sons and a daughter. The marriage ended in an ugly divorce in 1934. Later that year Frick remarried, to Margarete Schultze - Naumburg (1896 – 1960), the former wife of Paul Schultze - Naumburg. Margarete gave birth to a son and a daughter.

Frick finished school in Kaiserslautern. Between 1896 and 1900, he studied at the University of Munich, the University of Göttingen and the University of Berlin and completed his degree in law in Munich. Frick earned a doctor of laws from the University of Heidelberg in 1901.

Wilhelm Frick joined the NSDAP in September 1925 and worked for an insurance company. He took part in the Beer Hall Putsch (November 1923), at which time he was director of the Munich Kriminalpolizei. He was one of those arrested and imprisoned for the putsch and was tried for treason before the People's Court in April 1924. He was given a suspended sentence of 15 months' imprisonment and was dismissed from his police job. Frick was elected to the Reichstag in May 1924 and associated himself with the radical Gregor Strasser; he climbed to posts of leadership in the NSDAP, becoming Fraktionsführer (parliamentary leader) in 1928.

Wilhelm Frick was appointed Minister of the Interior and of Education in the state government of Thuringia during 1930 – 31, being the first Nazi to hold any ministerial level post in pre - Nazi Germany.

When Hitler came to power in January 1933, Frick was appointed as Reich Minister of the Interior. He was one of only three Nazis in the original Hitler Cabinet, the others being Hitler and Hermann Göring, as minister without portfolio. He initially had far less power than his counterparts in the rest of Europe. For example, he had no authority over the police. In Germany, law enforcement has traditionally been a state and local matter.

Frick's power dramatically increased as a result of the Reichstag Fire Decree and the Enabling Act of 1933. He was responsible for drafting many of the "Gleichschaltung" laws that consolidated the Nazi regime. Under the Law for the Reconstruction of the Reich, which converted Germany into a highly centralized state, the state governors were responsible to him. By 1935, he also had sole power to appoint the mayors of all municipalities with populations greater than 100,000 (except for Berlin and Hamburg, where Hitler reserved the right to appoint the mayors).

Frick was instrumental in passing laws against Jewish people, like the notorious Nuremberg Laws, in September 1935. Frick took a leading part in Germany's re-armament in violation of the Versailles Treaty. He drafted laws introducing universal military conscription and extending the military service law to Austria after the Anschluss, as well as to the annexed regions of Czechoslovakia. In the summer 1938 Wilhelm Frick was named the patron (Schirmherr) of the Deutsches Turn- und Sportfest in Breslau, a patriotic sports festival attended by Hitler and all the Nazi top brass. In this event he presided the ceremony of "handing over" the new Nazi Sports Officestandard (Bannerüberführung) to Hans von Tschammer und Osten, marking the further nazification of sports in Germany.

From the mid - to - late 1930s Frick lost favor irreversibly within the Nazi Party after a power struggle involving attempts to resolve the lack of coordination within the Reich government. For example, in 1933 he tried to restrict the widespread use of "protective custody" orders that were used to send people to concentration camps, only to be begged off by SS chief Heinrich Himmler. His power was greatly reduced in 1936 when Hitler named Himmler chief of all German police forces. This effectively united the police with the SS and made it virtually independent of Frick's control, since Himmler was responsible only to Hitler. A long running power struggle between the two culminated in Frick being replaced by Himmler as interior minister in 1943.

Frick's

replacement as Reich interior minister did not reduce, however, the

growing administrative chaos and infighting between party and state

agencies. Frick was then appointed to the ceremonial post of Protector of Bohemia and Moravia. Prague, the capital of the protectorate, where Frick used ruthless methods to counter dissent, was one of the last Axis held cities to fall at the end of World War II in Europe.

Frick was arrested and tried before the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, where he was the only defendant besides Rudolf Hess who refused to testify on his own behalf. For his role in formulating the Enabling Act as Minister of the Interior, the later Nuremberg Laws (as co-author with Wilhelm Stuckart), that led to people under those laws being sent to German concentration camps, Frick was convicted of planning, initiating and waging wars of aggression, war crimes and crimes against humanity. Frick was also accused of being one of the highest persons responsible for the existence of the concentration camps. Wilhelm Frick was sentenced to death on 1 October 1946, and was hanged about two weeks later on 16 October. Of his execution, journalist Howard K. Smith wrote:

- The sixth man to leave his prison cell and walk with handcuffed wrists to the death house was 69 - year - old Wilhelm Frick. He entered the execution chamber at 2.05 a.m., six minutes after Rosenberg had been pronounced dead. He seemed the least steady of any so far and stumbled on the thirteenth step of the gallows. His only words were, "Long live eternal Germany," before he was hooded and dropped through the trap.