<Back to Index>

- Reich Minister of Aviation Hermann Wilhelm Göring 1893

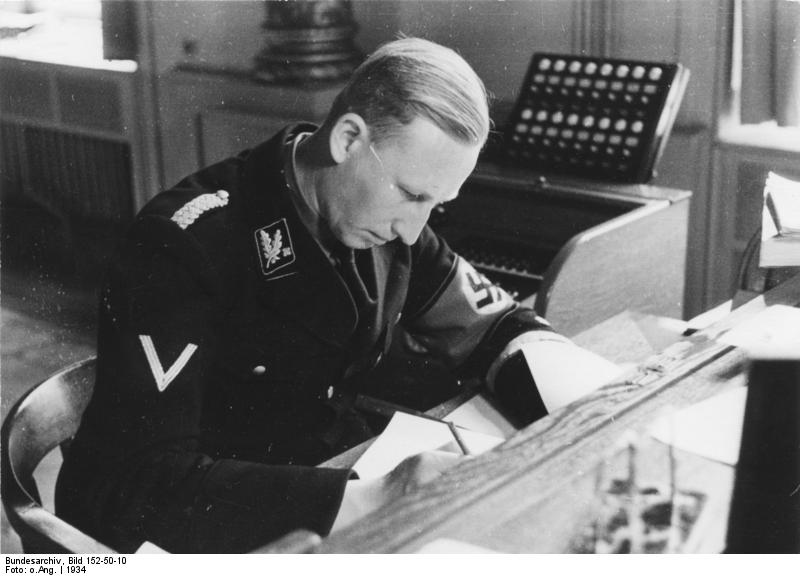

- Director of the Reich Main Security Office Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich 1904

PAGE SPONSOR

Hermann Wilhelm Göring, (or Goering; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader, and a leading member of the Nazi Party. He was a veteran of World War I as an ace fighter pilot, and a recipient of the coveted Pour le Mérite, also known as "The Blue Max". He was the last commander of Jagdgeschwader 1, the fighter wing once led by Manfred von Richthofen, "The Red Baron".

In 1935, Göring was appointed Commander - in - Chief of the Luftwaffe (German: Air Force), a position he held until the final days of World War II. By mid 1940, Göring was at the peak of his power and influence. Adolf Hitler had promoted him to the rank of Reichsmarschall, making Göring senior to all other Wehrmacht commanders, and in 1941 Hitler designated him as his successor and deputy in all his offices. By 1942, with the German war effort stumbling on both fronts, Göring's standing with Hitler was very greatly reduced. Göring largely withdrew from the military and political scene to enjoy the pleasures of life as a wealthy and powerful man. After World War II, Göring was convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity at the Nuremberg Trials. He was sentenced to death by hanging, but committed suicide by cyanide ingestion two hours before he was due to be hanged just after midnight.

Göring was born on 12 January 1893 at the Marienbad sanatorium in Rosenheim, Bavaria. His father Heinrich Ernst Göring (31 October 1839 – 7 December 1913) had been the first Governor General of the German protectorate of South West Africa (modern day Namibia) as

well as being a former cavalry officer and member of the German

consular service. Göring had among his paternal ancestors Eberle / Eberlin, a Swiss - German family of high bourgeoisie.

Göring was a relative of such Eberle / Eberlin descendants as the German aviation pioneer Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin; German romantic nationalist Hermann Grimm (1828 – 1901), an author of the concept of the German hero as a mover of history, whom the Nazis claimed as one of their ideological forerunners; the industrialist family Merck, the owners of the pharmaceutical giant Merck; German Baroness Gertrud von Le Fort, one of the world's major Catholic writers and poets of the 20th century, whose works were largely inspired by her revulsion against Nazism; and Carl J. Burckhardt, Swiss diplomat, historian, and President of the International Red Cross.

In a historical coincidence, Göring was related via the Eberle / Eberlin line to Jacob Burckhardt (1818 – 1897), a great Swiss scholar of art and culture who was a major political and social thinker as well an opponent of nationalism and militarism, who rejected German claims of cultural and intellectual superiority and predicted a cataclysmic 20th century in which violent demagogues, whom he called "terrible simplifiers", would play central roles.

Göring's mother Franziska "Fanny" Tiefenbrunn (1859 – 15 July 1923) came from a Bavarian peasant family. The marriage of a gentleman to a lower class woman occurred only because Heinrich Ernst Göring was a widower. Hermann Göring was one of five children; his brothers were Albert Göring and Karl Göring, and his sisters were Olga Therese Sophia Göring and Paula Elisabeth Rosa Göring, the last of whom were from his father's first marriage. Although antisemitism had become rampant in Germany at that time, his parents were not antisemitic.

Göring's younger brother Albert Göring was opposed to the Nazi regime and helped Jews and dissidents in Germany during the Nazi era, much like Oskar Schindler. In one instance, Albert helped Hermann himself by intervening on behalf of one of his wife’s film colleagues, Henny Porten.

Henny, an erstwhile sweetheart of German cinema, found herself

professionally ostracized after she refused to divorce her Jewish

husband, Dr. William von Kaufman. After meeting Henny in a Hamburg hotel

and learning of her predicament, Emmy Göring pleaded with Hermann

to call his younger brother Albert, who was, at the time, the technical

director of Tobis - Sascha Filmindustrie AG in Vienna. Hermann made the

call, and Albert duly arranged Henny a film contract in Vienna, ensuring

her a livelihood.

Göring's nephew — Hans - Joachim Göring — was a pilot in the Luftwaffe with III Gruppe./ZG 76, flying the Messerschmitt Bf 110. Hans - Joachim was killed in action on 11 July 1940, when his Bf 110 was shot down by Hawker Hurricanes of No. 78 Squadron RAF. His aircraft crashed into Portland Harbour, Dorset, England.

Göring later claimed his given name was chosen to honor the Arminius who defeated the Roman legions at Teutoburg Forest. However, the name was possibly to honor his godfather, a Christian of Jewish descent born Hermann Epenstein. Epenstein — whose father was an army surgeon in Berlin — became a wealthy physician and businessman and a major if not paternal influence on Göring's childhood. Hermann's father held diplomatic posts in Africa and in Haiti, climates considered too harsh for a young European child. This resulted in lengthy separation from his parents, and much of Hermann's very early childhood was spent with governesses and with distant relatives. Heinrich Göring retired circa 1898, and had to support his large family solely on his civil service pension. Thus for financial reasons the Görings became permanent house guests of their longtime friend, Göring's probable namesake. Epenstein had acquired a minor title (through service and donation to the Crown) and was now Hermann, Ritter von Epenstein.

Von Epenstein purchased two largely dilapidated castles, Burg Veldenstein in Bavaria and Burg Mauterndorf near Salzburg,

Austria, whose very expensive restorations were ongoing by the time of

Hermann Göring's birth. Both castles were to be residences of the

Göring family, their official "caretakers" until 1913. Both castles

also ultimately became Hermann's property.

According to some biographers of both Hermann Göring and his younger brother Albert Göring, soon after the family took residence in his castles, von Epenstein began an adulterous relationship with Frau Göring and may in fact have been Albert's father. (Albert's physical resemblance to von Epenstein was noted even during his childhood and is evident in photographs.) Whatever the nature of von Epenstein's relationship with his mother, the young Hermann Göring enjoyed a close relationship with his godfather.

Göring was initially unaware of von Epenstein's Jewish ancestry. He was enrolled in a prestigious Austrian boarding school, where his tuition was paid by von Epenstein. Then he wrote an essay in praise of his godfather and was mocked by the school's antisemitic headmaster for professing such admiration for a Jew. Göring denied the allegation, but was then presented with proof in the "Semi - Gotha", a book which cataloged German speaking nobility of insufficient status to be listed in the Almanach de Gotha. (Von Epenstein had bought his title and castles, and so was relegated to the lesser reference.) Göring remained steadfast in his devotion to his family's friend and patron so adamantly that he left the school and used what money he had to purchase a train ticket home. The action seems to have tightened the already considerable bond between godfather and godson.

Relations

between the Göring family and von Epenstein became far more formal

during Göring's adolescence (causing Mosley and other biographers

to speculate that perhaps the theorized affair ended naturally or that

the elderly Heinrich discovered he was a cuckold and threatened its

exposure). By the time of Heinrich Göring's death, the family no

longer lived in a residence supplied by von Epenstein, or seemed to have

much contact at all with him. The family's comfortable circumstances

indicate the Ritter may have continued to support them financially. Late

in his life, Ritter von Epenstein married Lily, a singer who was half

his age. He bequeathed her his estate in his will, but requested that

she in turn bequeath the castles at Mauterndorf and Veldenstein to his

godson Hermann upon her own death.

Göring was sent to boarding school at Ansbach, Franconia, and then attended the cadet institutes at Karlsruhe and the military college at Berlin Lichterfelde. Göring was commissioned in the Prussian army on 22 June 1912 in the Prinz Wilhelm Regiment (112th Infantry), headquartered at Mulhouse as part of the 29th Division of the Imperial German Army.

During the first year of World War I, Göring served with an infantry regiment in the Vosges region. He was hospitalized with rheumatism resulting from the damp of trench warfare. While he was recovering, his friend Bruno Loerzer convinced him to transfer to the Luftstreitkräfte ("air combat force") of the German army. Göring's transfer request was turned down. But later that year, Göring flew as Loerzer's observer in Feldfliegerabteilung 25 (FFA 25) – Göring had informally transferred himself. He was detected and sentenced to three weeks' confinement to barracks. The sentence was never carried out: by the time it was imposed Göring's association with Loerzer had been regularized. They were assigned as a team to FFA 25 in the Crown Prince's Fifth Army — "though it seems that they had to steal a plane in order to qualify." They flew reconnaissance and bombing missions for which the Crown Prince invested both Göring and Loerzer with the Iron Cross, first class.

On completing his pilot's training course he was posted back to FFA 2 in October 1915. Göring had already claimed two air victories as an Observer (one unconfirmed). He gained another flying a Fokker E.III single seater scout in March 1916. In October 1916, he was posted to Jagdstaffel 5, but was wounded in action in November. In February 1917, he joined Jagdstaffel 26. He now scored steadily until in May 1917, when he got his first command, Jasta 27. In June 1917, after a lengthy dogfight, Göring shot down Australian pilot Frank Slee. The battle is recounted in The Rise and Fall of Hermann Göring. Göring landed and met the Australian, and presented Slee with his Iron Cross. Years after, Slee gave Göring's Iron Cross to a friend, who later died on the beach during the Normandy Landings. Also during the war Göring had through his generous treatment made a friend of his prisoner of war Captain Frank Beaumont, a Royal Flying Corps pilot. "It was part of Goering's creed to admire a good enemy, and he did his best to keep Captain Beaumont from being taken over by the Army."

Serving with Jastas 5, 26 and 27, he continued to claim air victories. Besides the Iron Cross, he was awarded the Zaehring Lion with swords, the Friedrich Order and the House Order of Hohenzollern with swords, third class, and finally in May 1918, the coveted Pour le Mérite. On 7 July 1918, after the death of Wilhelm Reinhard, the successor of The Red Baron, he was made commander of the famed "Flying Circus", Jagdgeschwader 1.

Göring finished the war with 22 confirmed victories. Because of his arrogance, Göring's appointment as commander of Jagdgeschwader 1 had not been well received. According to Hermann Dahlmann, who knew both men, Göring had Loerzer lobby for a premature award of the Pour le Merite for Göring; in turn, Göring's subordinates resented the fact that he had been awarded the prestigious medal with only 18 victories to his credit, when 20 or more was the standard.

When demobilized during the first weeks of November 1918, Göring and his officers spent most of their time in the Stiftskeller, the best restaurant and drinking place in Aschaffenburg. Yet he was the only veteran of Jagdgeschwader 1 never invited to post war reunions.

Göring

was genuinely surprised (at least by his own account) at Germany's

defeat in World War I. He felt personally violated by the surrender, the

Kaiser's abdication, the humiliating terms, and the supposed treachery

of the post war German politicians who had "goaded the people [to

uprising] [and] who [had] stabbed our glorious Army in the back [thinking] of nothing but of attaining power and of enriching themselves at the expense of the people." Ordered

to surrender the planes of his squadron to the Allies in December 1918,

Göring and his fellow pilots intentionally wrecked the planes on landing. This action paralleled the scuttling of

surrendered ships. Typical for the political climate of the day, he was

not arrested or even officially reprimanded for his action.

He remained in flying after the war, worked briefly at Fokker, tried "barnstorming", and in 1921 he joined Svensk Lufttrafik, a Swedish airline. He was also listed on the officer rolls of the Reichswehr, the post World War I peacetime army of Germany, and by 1933 had risen to the rank of Generalmajor. He was made a Generalleutnant in 1935 and then a General in the Luftwaffe upon its founding later that year.

Göring as a veteran pilot was often hired to fly businessmen and others on private aircraft. He worked in Denmark and Sweden as a commercial pilot. One wintry evening he was hired by Count Eric von Rosen to fly him to his castle from Stockholm. Invited to spend the night there, it may have been here that Göring first saw the swastika emblem, a family badge which was set in the chimney piece around the roaring fire.

This was also the first time Göring saw his future wife. A great staircase led down into the hall opposite the fireplace. As Göring looked up he saw a woman coming down the staircase as if toward him. He thought she was very beautiful. The count introduced his sister - in - law Baroness Carin von Kantzow (née Freiin von Fock, 1888 – 1931) to the 27 year old Göring.

Carin was a tall, maternal, unhappy, sentimental woman five years Göring's senior, estranged from her husband and in delicate health. Göring was immediately smitten with her. Carin's eldest sister and biographer claimed that it was love at first sight. Carin was carefully looked after by her parents as well as by Count and Countess von Rosen. She was also married and had an eight year old son Thomas to whom she was devoted. No romance other than one of courtly love was possible at this point.

Carin divorced her estranged husband, Nils Gustav von Kantzow, in December 1922. She married Göring on 3 January 1923 in Stockholm.

Von Kantzow behaved generously. He provided a financial settlement

which enabled Carin and Göring to set up their first home together

in Germany. It was a hunting lodge at Hochkreuth in the Bavarian Alps, near Bayrischzell, some 50 mi (80 km) from Munich.

Göring joined the Nazi Party in 1922 and took over leadership of the Sturmabteilung (SA) as the Oberster SA - Führer. After stepping down as SA Commander, he was appointed an SA - Gruppenführer (Lieutenant General) and held this rank on the SA rolls until 1945. Hitler later recalled his early association with Göring thus:

I liked him. I made him the head of my S.A. He is the only one of its heads that ran the S.A. properly. I gave him a disheveled rabble. In a very short time he had organized a division of 11,000 men.

At this time, Carin — who liked Hitler — often played hostess to meetings of leading Nazis including her husband, Hitler, Hess, Rosenberg and Röhm.

Göring was with Hitler in the Beer Hall Putsch in

Munich on 9 November 1923. He marched beside Hitler at the head of the

SA. When the Bavarian police broke up the march with gunfire,

Göring was seriously wounded in the groin.

Although Göring was stricken with pneumonia, Carin arranged for him to be spirited away to Austria. Göring was in no way fit to travel and the journey may have aggravated his condition, although he did avoid arrest. Göring was X-rayed and operated on in the hospital at Innsbruck. Carin wrote to her mother from Göring's bedside on 8 December 1923 describing his terrible pain: "... in spite of being dosed with morphine every day, his pain stays just as bad as ever." This was the beginning of his morphine addiction, which lasted until his imprisonment at Nuremberg. Meanwhile in Munich the authorities declared Göring a wanted man.

The Görings — acutely short of funds and reliant on the good will of Nazi sympathizers abroad — moved from Austria to Venice, then in May 1924 to Rome via Florence and Siena. Göring met Benito Mussolini in Rome. Mussolini expressed some interest in meeting Hitler, by then in prison, on his release. Personal problems, however, continued to multiply. Göring's mother had died in 1923. By 1925, it was Carin's mother who was ill. The Görings — with difficulty — raised the money for a journey in spring 1925 to Sweden via Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Danzig. Göring had become a violent morphine addict and Carin's family were shocked by his deterioration when they saw him. Carin, herself an epileptic, had to let the doctors and police take full charge of Göring. He was certified a dangerous drug addict and placed in the violent ward of Långbro asylum on 1 September 1925. Biographer Roger Manvell quoted a Stockholm psychiatrist who had seen him before he was committed to Långbro: "Göring was very violent and had to be placed in a straitjacket but was not insane."

The 1925 psychiatrist's reports claimed Göring to be weak of character, a hysteric and unstable personality, sentimental yet callous, violent when afraid and a person whose bravado hid a basic lack of moral courage. "Like many men capable of great acts of physical courage which verge quite often on desperation, he lacked the finer kind of courage in the conduct of his life which was needed when serious difficulties overcame him."

At the time of Göring's detention, all doctors' reports in Sweden were matters of public record. In 1925, Carin sued for custody of her son. Nils von Kantzow, her ex-husband, used a doctor's report on Carin and Göring as evidence to show that neither of them was fit to look after the boy, and so von Kantzow kept custody. The reports were also used by political opponents in Germany.

Carin Göring died of heart failure on 17 October 1931.

Marinus van der Lubbe — an ex - Communist radical — was arrested on the scene and claimed sole responsibility for the Reichstag fire. But many observers believed that the Nazis set the fire to justify the subsequent crackdown. Göring in particular was suspected: he was first on the scene, and both Hitler and Goebbels were apparently surprised by the news. At Nuremberg, General Franz Halder testified that Göring admitted responsibility:

At a luncheon on the birthday of Hitler in 1942... [Göring said]... "The only one who really knows about the Reichstag is I, because I set it on fire!" With that he slapped his thigh with the flat of his hand.

William L. Shirer in his seminal study The Rise and Fall Of The Third Reich states that all of the evidence points strongly to the most unusual of possible scenarios being what actually happened, that Van der Lubbe coincidentally was present to start another fire at the same time that Göring and his accomplices also went into the Reichstag to start a different fire. While admitting how strange it sounds, the evidence that Shirer presents in his book makes a compelling case for this unusual situation.

Göring in his own Nuremberg testimony denied this story. It remains unclear whether Göring was responsible for the fire, although it seem fairly certain that van der Lubbe did enter the Reichstag with the intent to commit arson. The following is a transcript excerpt from the Nuremberg Trials:

GOERING: This conversation did not take place and I request that I be confronted with Herr Halder. First of all I want to emphasize that what is written here is utter nonsense. It says, "The only one who really knows the Reichstag is I." The Reichstag was known to every representative in the Reichstag. The fire took place only in the general assembly room, and many hundreds or thousands of people knew this room as well as I did. A statement of this type is utter nonsense. How Herr Halder came to make that statement I do not know. Apparently that bad memory, which also let him down in military matters, is the only explanation.

MR. ROBERT JACKSON: You know who Halder is?

GOERING: Only too well.

GOERING: That accusation that I had set fire to the Reichstag came from a certain foreign press. That could not bother me because it was not consistent with the facts. I had no reason or motive for setting fire to the Reichstag. From the artistic point of view I did not at all regret that the assembly chamber was burned – I hoped to build a better one. But I did regret very much that I was forced to find a new meeting place for the Reichstag and, not being able to find one, I had to give up my Kroll Opera House, that is, the second State Opera House, for that purpose. The opera seemed to me much more important than the Reichstag.

MR. ROBERT JACKSON: Have you ever boasted of burning the Reichstag building, even by way of joking?

GOERING: No. I made a joke, if that is the one you are referring to, when I said that, ′after this, I should be competing with Nero and that probably people would soon be saying that, dressed in a red toga and holding a lyre in my hand, I looked on at the fire and played while the Reichstag was burning′. That was the joke. But the fact was that I almost perished in the flames, which would have been very unfortunate for the German people, but very fortunate for their enemies.

MR. ROBERT JACKSON: You never stated then that you burned the Reichstag?

GOERING: No. I know that Herr Rauschning said in the book which he wrote, and which has often been referred to here, that I had discussed this with him. I saw Herr Rauschning only twice in my life and only for a short time on each occasion. If I had set fire to the Reichstag, I would presumably have let that be known only to my closest circle of confidants, if at all. I would not have told it to a man whom I did not know and whose appearance I could not describe at all today. That is an absolute distortion of the truth.

During the early 1930s Göring was often in the company of Emmy Sonnemann (1893 – 1973), an actress from Hamburg. He proposed to her in Weimar in February 1935. The wedding took place on 10 April 1935 in Berlin and was celebrated like the marriage of an emperor. They had a daughter, Edda Göring (born 2 June 1938) who was reportedly named after Countess Edda Ciano, eldest child of Benito Mussolini, although other sources say she was named after a friend of her mother. Edda's Godfather was Adolf Hitler.

When Hitler was named chancellor of Germany in January 1933, Göring was appointed as minister without portfolio. He was one of only two other Nazis named to the Cabinet (the other being Wilhelm Frick) even though the Nazis were the largest party in the Reichstag and nominally the senior partner in the Nazi - DNVP coalition. However, in a little noticed development, he was named Interior Minister of Prussia — a move which gave him command of the largest state police force in Germany. Soon after taking office, he began filling the political and intelligence units of the Prussian police with Nazis. On 26 April 1933, he formally detached these units from the regular Prussian police and reorganized them under his command as the Gestapo, a secret state police intended to serve the Nazi cause.

Göring was one of the key figures in the process of Gleichschaltung ("forcible coordination") that established the Nazi dictatorship. For example, in 1933, Göring banned all Roman Catholic newspapers

in Germany, not only to suppress resistance to National Socialism but

also to deprive the population of alternative forms of association and

means of political communication.

In the Nazi regime's early years, Göring served as minister in various key positions at both the Reich (German national) level and other levels as required. For example, in the state of Prussia, Göring was responsible for the economy as well as re-armament.

In 1934 / 35, Göring, acting as Prussian Prime Minister, was intimately involved in the dubious acquisition of the Guelph Treasure of Brunswick (the so-called "Welfenschatz") – a unique collection of early medieval religious precious metalwork, at that time in the hands of some persecuted German - Jewish art dealers from Frankfurt, and one of the most important church treasuries to have survived from medieval Germany.

On 20 April 1934, Göring and Himmler agreed to put aside their differences (largely because of mutual hatred and growing dread of the SA or Sturmabteilung) and Göring transferred full authority over the Gestapo to Himmler, who was also named chief of all German police forces outside Prussia. With the Gestapo under their control, Himmler and Heydrich plotted — with Göring — to use it with the SS to crush the SA. Göring retained Special Police Battalion Wecke, which he converted to a paramilitary unit attached to the Landespolizei (State Police), Landespolizeigruppe General Göring. This formation participated in the Night of the Long Knives, when the SA leaders were purged. Göring was head of the Forschungsamt (FA), which secretly monitored telephone and radio communications, the FA was connected to the SS, the SD, and Abwehr intelligence services.

In 1936, he became Plenipotentiary of the Four Year Plan for German rearmament, where he effectively took control of the economy — as economics minister Hjalmar Schacht became increasingly reluctant to pursue rapid rearmament and eventually resigned. The vast steel plant Reichswerke Hermann Göring was named after him. He gained great influence with Hitler (who placed a high value on rearmament). He never seemed to accept the Hitler Myth quite as much as Goebbels and Himmler, but remained loyal nevertheless.

In 1938, Göring forced out the War Minister, Field Marshal Werner von Blomberg, and the Army commander, General von Fritsch. They had welcomed Hitler's accession in 1933, but then annoyed him by criticizing his plans for expansionist wars. Göring, who had been best man at Blomberg's recent wedding to a 26 year old typist, discovered that Frau Blomberg had a criminal record for posing for pornographic photos in 1932, which Göring misrepresented as being for prostitution as a way of smearing her husband. This led to Blomberg's resigning. Fritsch was accused of homosexual activity and, though completely innocent, resigned in shock and disgust. He was later exonerated by a "court of honor" presided over by Göring.

Also in 1938, Göring played a key role in the Anschluss (annexation) of Austria. At the height of the crisis, Göring spoke on the telephone to Austrian Chancellor Schuschnigg.

Göring announced Germany's intent to march into Austria, and

threatened war and the destruction of Austria if there was any

resistance. Schuschnigg collapsed, and the German army marched into

Austria without resistance.

The confiscation of Jewish property gave Göring great opportunities to amass a personal fortune. Some properties he seized himself, or acquired for a nominal price. In other cases, he collected bribes for allowing others to steal Jewish property. He also took kickbacks from industrialists for favorable decisions as Four Year Plan director, and money for supplying arms to the Spanish Republicans in the Spanish Civil War via Pyrkal in Greece (although Germany was supporting Franco and the Nationalists).

Göring also "collected" several other offices, such as Reichsforst - und Jägermeister (Reich Master of the Forest and Hunt), for which he received high government salaries. His Chief Huntsman was Walter Frevert.

In 1933, Göring acquired a vast estate in the Schorfheide Forest in Brandenburg, 40 km (25 mi) northeast of Berlin, and built his great manor house there. It was named Carinhall in memory of his first wife Carin. He exulted in aristocratic trappings, such as a coat of arms, and ceremonial swords and daggers, such as the Wedding Sword (an oversized broadsword with elaborate gold hilt presented to Göring at his 1935 wedding to Emmy). He also owned many uniforms and jewelry.

Göring was also noted for his patronage of music, especially opera. He entertained frequently and lavishly. Most infamously, he collected art, looting from numerous museums (some in Germany itself), stealing from Jewish collectors, or buying for grossly discounted prices in occupied countries.

When Göring was promoted to the unique rank of Reichsmarschall, he designed an elaborate personal flag for himself. The design included a German eagle, swastika, and crossed marshal's batons on one side, and on the other the Großkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes ("Grand Cross of the Iron Cross") between four Luftwaffe eagles. He had the flag carried by a personal standard bearer at all public occasions.

Göring was known for his extravagant tastes and garish clothing. Hans - Ulrich Rudel, the top Stuka pilot of the war, recalled twice meeting Göring dressed in outlandish costumes: first, a medieval hunting costume, practicing archery with his doctor, and second, dressed in a russet toga fastened with a golden clasp, smoking an abnormally large pipe. Italian Foreign Minister Ciano once noted Göring wearing a fur coat looking like what "a high grade prostitute wears to the opera." His personal car — dubbed "The Blue Goose" — was an aviation blue Mercedes 540K Special Cabriolet. It had luxurious features, as well as special additions, including bullet proof glass and bomb resistant armor for protection, and modifications to allow him to fit his girth behind the wheel.

Though he liked to be called "der Eiserne"

(the Iron Man), the once dashing and muscular fighter pilot had become

corpulent. He was however one of the few Nazi leaders who did not take

offence at hearing jokes about himself, "no matter how rude," taking

them as a sign of his popularity. Germans joked about his ego, saying

that he would wear an admiral's uniform to take a bath, and his obesity,

joking that "he sits down on his stomach."

Göring was certainly an ardent Nazi and utterly loyal to Hitler. But his

preferences in foreign policy were different. The German diplomatic

historian Klaus Hildebrand in

his study of German foreign policy in the Nazi era noted that besides

Hitler's foreign policy program that there were three rival programs

supported by factions in the Nazi Party, whom Hildebrand dubbed the

agrarians, the revolutionary socialists, and the Wilhelmine

Imperialists.

Göring was the most prominent of the Wilhelmine Imperialists. This group wanted to restore the German frontiers of 1914, regain the pre 1914 overseas empire, and make Eastern Europe Germany's exclusive sphere of influence. This was a much more limited set of goals than Hitler's dream of Lebensraum to be carved out with merciless racial wars. By contrast, Göring and the Wilhelmine Imperialist faction were more guided by traditional Machtpolitik in their foreign policy conceptions. Furthermore, they expected to achieve their goals within the established international order. While not rejecting war as an option, they preferred diplomacy and sought political domination in eastern Europe rather than the military conquests envisioned by Hitler. They also rejected Hitler's mystical vision of war as a necessary ordeal for the nation, and of perpetual war as desirable. Göring himself feared that a major war might interfere with his luxurious lifestyle. Göring's advocacy of this policy led to his temporary exclusion by Hitler for a time in 1938 – 1939 from foreign policy decisions. Göring's unwillingness to offer a major challenge to Hitler prevented him from offering any serious resistance to Hitler's policies, and the Wilhelmine Imperialists had no real influence.

Göring had some private doubts about the wisdom of Hitler’s policies attacking Poland, which he felt would cause a world war, and was anxious to see a compromise solution. This was especially the case as the Forschungsamt (FA), Göring's private intelligence agency, had broken the codes the British Embassy in Berlin used to communicate with London. The FA's work showed that British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was determined to go to war if Germany invaded Poland in 1939. This directly contradicted the advice given to Hitler by Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop (a man whom Göring loathed at the best of times) that Chamberlain would not honor the “guarantee” he had given Poland in March 1939 if Germany attacked that country.

In

the summer of 1939, Göring and the rest of the Wilhelmine

Imperialists made a last ditch effort to assert their foreign policy

program. Göring was involved in desperate attempts to avert a war

by using various amateur diplomats, such as his deputy Helmuth Wohltat

at the Four Year Plan organization, British civil servant Sir Horace Wilson, newspaper proprietor Lord Kemsley, and would be peace makers like Swedish businessmen Axel Wenner - Gren and Birger Dahlerus, who served as couriers between Göring and various British officials. All

of these efforts came to naught because Hitler (who much preferred

Ribbentrop’s assessment of Britain to Göring's) would not be

deterred from attacking Poland in 1939, and the Wilhelmine Imperialists

were unwilling and unable to challenge Hitler despite their reservations

about his foreign policy.

Göring was responsible for the Nuremberg laws and for charging Jews with a billion reichsmark fine for Kristallnacht, which he never denied at his trial. However, his role in and awareness of the extermination of the Jews is much more controversial.

Göring claimed at Nuremberg that he was not anti - Semitic, and it is generally accepted that the anti - Semitism of Goebbels and Himmler was far stronger than that of Göring, who was more cynical than ideological in all of his attitudes. He occasionally intervened to shield individual Jews from harm, (including his own deputy, Erhard Milch) sometimes in exchange for a bribe, sometimes after a request from his wife Emmy or his anti - Nazi brother Albert. Göring despised Himmler and he often sparred with Goebbels who was in favor of more radical measures against the Jews. However, some of the quotes provided at the Nuremberg trial show his apparent antisemitic side, though much milder than that of Goebbels or Himmler, some apparently said as ironic retorts to Goebbels. Despite his sporadic actions to help individuals, Göring was deemed complicit in the Holocaust: he was the highest figure in the Nazi hierarchy to issue a written order for the "complete solution of the Jewish Question", as he issued a memo to Reinhard Heydrich to organize the practical details. Göring, who issued this memo in place of Hitler, which he occasionally did, wrote in the memo to "submit to me as soon as possible a general plan of the administrative, financial and material measures necessary for carrying out the desired Final Solution of the Jewish question." This was in July 1941, many months before, according to most historians, the decision to exterminate Jews was taken. Göring, who at Nuremberg trial unrepentantly took responsibility for his actions, as opposed to most other defendants who blamed Hitler, maintained to his death that this meant relocation of Jews, and that he did not know of the subsequent extermination. Following this transfer of the Jewish question to Heydrich and Himmler, at the Wannsee Conference in early 1942, the Holocaust was planned with Heydrich as the most senior officer present, reporting directly to Himmler.

In 1989, historian and noted Nazi sympathizer David Irving published a biography of Göring, which in part said that he had disapproved of the persecution of Jews and offered documented evidence as proof. Much of Irving's work, however, has been discredited, and Göring's complicity in the Final Solution remains a point of contention.

When

the Nazis took power, Göring was Minister of Civil Air Transport,

which was a screen for the build-up of German military aviation,

prohibited by the Treaty of Versailles. When Hitler repudiated Versailles, in 1935, the Luftwaffe was unveiled, with Göring as Minister and Oberbefehlshaber (Supreme Commander). In 1938, he became the first Generalfeldmarschall (Field Marshal) of the Luftwaffe;

this promotion also made him the highest ranking officer in Germany.

Göring directed the rapid creation of this new branch of service.

Within a few years, Germany produced large numbers of the world's most

advanced military aircraft.

In 1936, Göring at Hitler's direction sent several hundred aircraft along with several thousand air and ground crew, to assist the Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War. This became known as the Condor Legion.

By 1939, the Luftwaffe was one of the most advanced and powerful air forces in the world.

Unusually, the Luftwaffe also included its own ground troops, which became in a sense, Göring's private army. German Fallschirmjäger (parachute and glider) troops were organized as part of the Luftwaffe, not as part of the Army. Subject to rigorous training, they came to be regarded as elite troops, much the same as the paratroopers of the British and American armies. Fallschirmjäger units were awarded 134 Knight's Cross of the Iron Crosses between the years 1940 – 1945.

In addition to the Fallschirmjäger, there were also the Luftwaffe Field Divisions,

which were organized as basic infantry units but were led by officers

with little training for ground combat, and generally performed badly as

combat troops as a result. The Hermann Göring Panzerdivision was also raised and served with distinction in the Italian campaign.

Göring was skeptical of Hitler's war plans. He believed Germany was not prepared for a new conflict and, in particular, that his Luftwaffe was not yet ready to beat the British Royal Air Force (RAF).

However, once Hitler decided on war, Göring supported him completely. On 1 September 1939, the first day of the war, Hitler spoke to the Reichstag. In this speech, he designated Göring as his successor "if anything should befall me."

Initially, decisive German victories followed quickly one after the other. The Luftwaffe destroyed the Polish Air Force within two weeks. The Fallschirmjäger seized key airfields in Norway and captured Fort Eben - Emael in Belgium. German air - to - ground attacks served as the "flying artillery" of the Panzertroops in the blitzkrieg of France. "Leave it to my Luftwaffe" became Göring's perpetual gloat.

After the defeat of France, Hitler awarded Göring the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross for his successful leadership. By a decree on 19 July 1940, Hitler promoted Göring to the rank of Reichsmarschall des Grossdeutschen Reiches (Reich Marshal of the Greater German Reich), a special rank which made him senior to all other Army and Luftwaffe Field Marshals. It also reinforced his status as Hitler's chosen successor, as a result of which the Führer gave Göring personal use of Kransberg Castle.

Göring's political and military careers were at their peak. Göring had already received the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross on 30 September 1939 as Commander in Chief of the Luftwaffe.

Göring promised Hitler that the Luftwaffe would quickly destroy the RAF, or break British morale with devastating air raids. He personally directed the first attacks on Britain from his private luxury train. But the Luftwaffe failed to gain control of the skies in the Battle of Britain. This was Hitler's first defeat. Britain withstood the worst Luftwaffe bombers could do for the eight months of "the Blitz" without being cowed by circumstances. However, the damage inflicted on British cities largely maintained Göring's prestige. The Luftwaffe conducted bombings of Belgrade in April 1941, and Fallschirmjäger captured Crete from the British Army the following month.

If

Göring had been skeptical about war against Britain and France, he

was absolutely certain that a new campaign against the Soviet Union was doomed to defeat. After trying, completely in vain, to convince Hitler to give up Operation Barbarossa,

he embraced the campaign. Hitler still relied on him completely. On 29

June, Hitler composed a special 'testament', which was kept secret till

the end of the war. This formally designated Göring as "my deputy

in all my offices" if Hitler was unable to function as dictator of

Germany, and his successor if he died. Ironically, Göring did not

know the contents of this testament, which was marked "To be opened only

by the Reichsmarschall", until after leaving Berlin in April 1945 for Berchtesgaden, where it had been kept.

The Luftwaffe shared in the initial victories in the east, destroying thousands of Soviet aircraft. But as Soviet resistance grew and the weather turned bad, the Luftwaffe became overstretched and exhausted.

Göring by this time had lost interest in administering the Luftwaffe. That duty was left to others like Udet and Jeschonnek. Aircraft production lagged and Udet killed himself in November 1941. Yet Göring persisted in outlandish promises. When the Soviets surrounded a German army in Stalingrad in 1942, Göring encouraged Hitler to fight for the city rather than retreat. He asserted that the Luftwaffe would deliver 500 short tons (450 t) per day of supplies to the trapped force. In fact, no more than 100 short tons (91 t) were ever delivered in a day, and usually much less. While Göring's men struggled to fly in the savage Russian winter, Göring celebrated his 50th birthday.

Göring

was in charge of exploiting the vast industrial resources captured

during the war, particularly in the Soviet Union. This proved to be an

almost total failure, and little of the available potential was

effectively harnessed for the service of the German military machine.

On 9 August 1939, Göring boasted "The Ruhr will not be subjected to a single bomb. If an enemy bomber reaches the Ruhr, my name is not Hermann Göring: you can call me Meier!" ("I want to be called Meier if ..." is a German idiom to express that something is impossible. Meier [in several spelling variants] is the second most common surname in Germany.) He also said he would eat his hat.

But as early as 1940, British aircraft raided targets in Germany, debunking Göring's assurance that the Reich would never be attacked; the British were — throughout the war — destined to be his personal undoing. However, the initial raids were unsuccessful in inflicting significant damage to German infrastructure, allowing Göring to reassure the public especially as the German air defense network improved. However, in 1942 the British Area Bombing Directive was issued, the main workhorse aircraft of the later part of the war came into service (the Halifax and Lancaster made up the backbone of the Command, and had a longer range, higher speed and much greater bomb load than the earlier aircraft; the classic aircraft of the Pathfinders, the de Havilland Mosquito, also made its appearance) and America began transferring long range strategic bombers to England for further air raids.

By 1942, hundreds of Allied bombers were bombing Germany; occasionally, there were as many as 1,000. The Luftwaffe responded with night fighters and anti - aircraft guns, but entire cities such as Cologne (Köln) and Hamburg were

destroyed anyway. Göring was still nominally in charge, but in

practice he had little to do with operations. When Göring visited

the devastated cities, civilians called out "Hello, Mr. Meier. How's

your hat?" By the end of the war, Berlin's air raid sirens were

bitterly known to the city's residents as "Meier's trumpets", or

"Meier's hunting horns". Civilians would also call the bomber war "a

defeat in every city".

The Luftwaffe's own efforts at having a strategic bomber force had been crippled even before the war began, from the death in 1936 of General Walter Wever, the Luftwaffe's primary promoter for Germany to have a strategic bombing capability, and a subsequent placement of greater value on medium bombers such as the Heinkel He 111, and Schnellbomber fast medium bombers, such as the Junkers Ju 88. Belated efforts in replacement designs of greater performance in altitude, speed and range, such as the Bomber B development program and Amerika Bomber trans - oceanic range strategic bomber design competition, either never worked out due to inadequate powerplants or the inability to complete the development of new airframe designs from the constantly worsening war and aircraft production facility situation. These problems led to the Luftwaffe continuing to primarily use the pre - war origin medium bomber designs, or barely upgraded versions of them. The only German aircraft design of a comparable capability and size to Allied heavy bombers such as the B-17 to see wartime service, the troubled Heinkel He 177 Greif, had been afflicted with having to use a set of four DB 601 engines paired up into twin "power systems" as the "DB 606", partly due to its mis - assignment as a "giant Stuka" from its beginnings heavily influencing its design. By September 1942, Goering had roundly derided the DB 606, and its later development, the DB 610, as fire prone, monstrous zusammengeschweißte Motoren, or "welded - together engines", that could not be properly maintained in service as installed in the He 177A, the one German aircraft design that Goering is said to have despised the most during the war years.

Göring's

prestige, reputation, and influence with Hitler all declined,

especially after the Stalingrad debacle. Hitler could not publicly

repudiate him without embarrassment, but contact between them largely

stopped. Göring withdrew from the military and political scene to

enjoy the pleasures of life as a wealthy and powerful man. His

reputation for extravagance made him particularly unpopular as ordinary

Germans began to suffer deprivation.

In 1945, Göring fled the Berlin area with trainloads of treasures for the Nazi alpine resort in Berchtesgaden. Soon afterward, the Luftwaffe's chief of staff, Karl Koller, arrived with unexpected news: Hitler — who had by this time conceded that Germany had lost — had suggested that Göring would be better suited to negotiate peace terms. To Koller, this seemed to indicate that Hitler wanted Göring to take over the leadership of the Reich.

Göring was initially unsure of what to do, largely because he did not want to give Martin Bormann, who now controlled access to Hitler, a window to seize greater power. He thought that if he waited he'd be accused of dereliction of duty. On the other hand, he feared being accused of treason if he did try to assume power. He then pulled his copy of Hitler's secret decree of 1941 from a safe. It clearly stated that Göring was not only Hitler's designated successor, but was to act as his deputy if Hitler ever became incapacitated. Göring, Koller, and Hans Lammers — the state secretary of the Reich Chancellery — all agreed that Hitler faced almost certain death by staying in Berlin to lead the defense of the capital against the Soviets. They also agreed that by staying in Berlin, Hitler had incapacitated himself from governing and Göring had a clear duty to assume power as Hitler's deputy.

On 23 April, as Soviet troops closed in around Berlin, Göring sent a carefully worded telegram by radio to Hitler, asking Hitler to confirm that he was to take over the "total leadership of the Reich." He added that if he did not hear back from Hitler by 22:00, he would assume Hitler was incapacitated, and would assume leadership of the Reich. A few minutes later, he sent a radio message to Ribbentrop stating that if the foreign minister got no further word, he was to come to Berchtesgaden immediately.

However, Bormann received the telegram before Hitler did. He portrayed it as an ultimatum to surrender power or face a coup d'état. The message to Ribbentrop, suggesting that Göring was already acting as Hitler's successor, provided further ammunition for Bormann. On 25 April, Hitler issued a telegram to Göring telling him that he had committed "high treason" and gave him the option of resigning all of his offices in exchange for his life. However, not long after that, Bormann ordered the SS in Berchtesgaden to arrest Göring. In his last will and testament, Hitler dismissed Göring from all of his offices and expelled him from the Nazi Party.

Shortly

after Hitler completed his will, Bormann ordered the SS to execute

Göring, his wife, and their daughter (Hitler's own goddaughter) if

Berlin were to fall. But this order was ignored. Instead, the

Görings and their SS captors moved together, to the same Schloß Mauterndorf where

Göring had spent much of his childhood and which he had inherited

(along with Burg Veldenstein) from his godfather's widow in 1938.

(Göring had arranged for preferential treatment for the woman, and

protected her from confiscation and arrest as the widow of a wealthy

Jew.)

Göring surrendered to U.S. soldiers on 9 May 1945 in Bavaria. He was flown by United States Army pilot Mayhew Foster from Austria to Germany, where he was debriefed and then in November of that same year tried in Nuremberg for war crimes. He was the third highest ranking Nazi official tried at Nuremberg, behind Reich President (former Admiral) Karl Dönitz and former Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess. Göring's last days were spent with Captain Gustave Gilbert, a German speaking American intelligence officer and psychologist, who had access to all the prisoners held in the Nuremberg jail. Gilbert classified Göring as having an I.Q. of 138, the same as Dönitz. Gilbert kept a journal which he later published as Nuremberg Diary. Here he describes Göring on the evening of 18 April 1946, as the trials were halted for a three day Easter recess:

Sweating in his cell in the evening, Göring was defensive and deflated and not very happy over the turn the trial was taking. He said that he had no control over the actions or the defense of the others, and that he had never been anti - Semitic himself, had not believed these atrocities, and that several Jews had offered to testify on his behalf.

In taking the witness stand during his part of the trial, Göring claimed that he was not antisemitic; however, Albert Speer reported that in the prison yard at Nuremberg, after someone made a remark about Jewish survivors in Hungary, he had overheard Göring say, "So, there are still some there? I thought we had knocked off all of them. Somebody slipped up again." Despite his claims of non - involvement, he was confronted with orders he had signed for the murder of Jews and prisoners of war.

Though he defended himself vigorously, and actually appeared to be winning the trial early on (partly by building popularity with the court audience by making jokes and finding holes in the prosecution's case), he was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. The judgment stated that:

There is nothing to be said in mitigation. For Göring was often, indeed almost always, the moving force, second only to his leader. He was the leading war aggressor, both as political and as military leader; he was the director of the slave labour programme and the creator of the oppressive programme against the Jews and other races, at home and abroad. All of these crimes he has frankly admitted. On some specific cases there may be conflict of testimony, but in terms of the broad outline, his own admissions are more than sufficiently wide to be conclusive of his guilt. His guilt is unique in its enormity. The record discloses no excuses for this man.

Göring made an appeal, offering to accept the court's death sentence if he were shot as a soldier instead of hanged as a common criminal, but the court refused.

Defying the sentence imposed by his captors, he committed suicide with a potassium cyanide capsule the night before he was to be hanged. Göring — who suffered from dermatitis — had hidden two cyanide capsules in jars of opaque skin cream. It has been claimed that Göring befriended U.S. Army Lieutenant Jack G. Wheelis, who was stationed at the Nuremberg Trials and helped Göring obtain cyanide which had been hidden among Göring's personal effects when they were confiscated by the Army. In 2005, former U.S. Army Private Herbert Lee Stivers claimed he gave Göring "medicine" hidden inside a gift fountain pen from a German woman the private had met and flirted with. Stivers served in the 1st Infantry Division's 26th Infantry Regiment, who formed the honor guard for the Nuremberg Trials. Stivers claims to have been unaware of what the "medicine" he delivered actually was until after Göring's death. Göring's biographer, David Irving, has dismissed this claim as pure fabrication. Because he committed suicide, his dead body was displayed by the gallows for the witnesses of the executions.

After their deaths, the bodies of Göring and the executed Nazi leaders were cremated in the East Cemetery, Munich (Ostfriedhof). His ashes were disposed of in the Isar river in Munich.

Göring spoke about war and extreme nationalism to Captain Gilbert, as recorded in Gilbert's Nuremberg Diary:

Naturally, the common people don't want war; neither in Russia nor in England nor in America, nor for that matter in Germany. That is understood. But, after all, it is the leaders of the country who determine the policy and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy or a fascist dictatorship or a Parliament or a Communist dictatorship. ...voice or no voice, the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is to tell them they are being attacked, and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same way in any country.

The well - known quotation, and its variations,

Whenever I hear the word culture, the first thing I will do is reach for my gun.

is

frequently attributed to Göring during the inter - war period.

Whether or not he actually used this phrase is unclear; it did not

originate with him. The line comes from Nazi playwright Hanns Johst's play Schlageter, "Wenn ich Kultur höre ... entsichere ich meinen Browning" ("Whenever I hear of culture... I release the safety - catch of my Browning"). Nor was Göring the only Nazi official to use this phrase: Rudolf Hess used

it as well, and it was a popular cliché in Germany, often in the

form: "Wenn ich 'Kultur' höre, nehme ich meine Pistole."

("Whenever I hear 'culture', I take my pistol" or "When I hear of

culture, I pick up my gun.")

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich (7 March 1904 – 4 June 1942) was a high ranking German Nazi official.

Heydrich was SS - Obergruppenführer (Lieutenant General) and General der Polizei, chief of the Reich Main Security Office (including the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), Gestapo, and Kripo) and Stellvertretender Reichsprotektor (Deputy Reich Protector) of Bohemia and Moravia. In August 1940, he was appointed and served as President of Interpol (the international law enforcement agency). Heydrich chaired the January 1942 Wannsee Conference, which laid out plans for the final solution to the Jewish Question — the deportation and extermination of all Jews in German occupied territory.

He was attacked in Prague on 27 May 1942 by a British trained team of Czech and Slovak soldiers who had been sent on behalf of the Czechoslovak government - in - exile to kill him in an operation named Operation Anthropoid. He died from his injuries a week later. Intelligence falsely linked the assassins to the towns of Lidice and Ležáky. In retaliation, Heinrich Himmler ordered over 13,000 people arrested. The village of Lidice was razed to the ground and all but a handful of its women and children were deported and killed in Nazi concentration camps; all male residents over the age of 16 (192 in total) were shot by firing squads. At least 1,300 people were murdered in the wake of Heydrich's death.

Historians regard him as the darkest figure within the Nazi elite. Hitler christened him "The Man with the Iron Heart".

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich was born in Halle an der Saale to composer and opera singer Richard Bruno Heydrich and his wife Elisabeth Anna Maria Amalia Krantz, a Roman Catholic. His two forenames were patriotic musical references: "Reinhard" was the name of the tragic hero from Amen, an opera written by his father, while "Tristan" stems from Richard Wagner's Tristan und Isolde.

His third name, "Eugen", was the name of his late maternal grandfather,

Professor Eugen Krantz, who had been the director of the Dresden Royal Conservatory. Heydrich

was born into a family of social standing and substantial financial

means. Music was a part of Heydrich's everyday life; his father was the

founder of the Halle Conservatory of Music. His mother, Elisabeth, was a

piano instructor there. Heydrich

developed a passion for the violin, a passion he carried into his adult

life; he impressed listeners with his musical talent.

His father was a German nationalist who instilled patriotic ideas in the minds of his three children, but was never affiliated with any party until after World War I. The Heydrich household was strict. As a youth, Heydrich engaged his younger brother, Heinz, in mock fencing duels. Heydrich was very intelligent and excelled in his schoolwork at the "Reformgymnasium", especially in science. A talented athlete, he became an expert swimmer and fencer. He was shy, insecure, and was frequently bullied for his high pitched voice. Heydrich was often mocked in his youth, being nicknamed "Moses Handel" due to rumours that he had Jewish ancestry. Years later, Wilhelm Canaris said he had obtained photocopies proving Heydrich's Jewish ancestry, but these photocopies never surfaced. Rudolf Jordan also made the claim that Heydrich was not a pure "Aryan". Heydrich ordered Schutzstaffel (SS) researchers to investigate the rumour. They established that he had no Jewish ancestors. Achim Gercke concluded that Heydrich was a pure Aryan.

In

1918, World War I ended with Germany's defeat. In late February 1919,

civil unrest took place in Heydrich's home town of Halle. There were

strikes and clashes between communist and anti - communist groups. Under

Defense Minister Gustav Noske's directives, a right wing paramilitary unit was formed and ordered to "recapture" the city of Halle. 15 year old Heydrich joined Maercker's Volunteer Rifles (the first Freikorps unit). After the skirmishes had ended, Heydrich was part of the force assigned to protect private property. Little is known as to Heydrich's role, but the events left a strong impression; it was a "political awakening" for him. He joined the Deutschvölkischer Schutz und Trutzbund (The National German Protection and Shelter League), an anti - Semitic organisation.

Because of the conditions of the Treaty of Versailles, hyperinflation spread across Germany and many people lost their life savings. By 1921, these events greatly reduced the ability of the people of Halle to afford a musical education at Bruno Heydrich's conservatory. This led to a financial crisis for the Heydrich family.

In 1922 Reinhard Heydrich joined the Navy, taking advantage of the security, structure and pension it offered. He became a naval cadet at Germany's chief naval base at Kiel. On 1 April 1924 Heydrich was promoted to senior midshipman and sent off to officer training at the Mürwik Naval College. In 1926 he advanced to the rank of ensign (Leutnant zur See) and was assigned as a signals officer on the battleship Schleswig - Holstein, the flagship of the German North Sea Fleet. With the promotion came greater recognition; he received good evaluations from his superiors. He had fewer problems with other crewmen, but the increased rank drove his ambition and arrogance.

Heydrich became a notorious womaniser, having countless affairs. In December 1930 he attended a rowing club ball and met Lina von Osten.

The two became romantically involved and soon announced their

engagement. Lina was already a Nazi Party follower; she had attended her

first rally in 1929. A former lover whom Heydrich had known for over six months became

infuriated that he was to marry another woman. She complained to her

father, who in turn contacted Admiral Erich Raeder,

then Chief of Naval Operations. A formal complaint was filed against

Heydrich for insulting the honor of a woman and breaking an engagement

promise. He

was charged with "conduct unbecoming to an officer and a gentleman" and

ordered before a military court of honor. Heydrich protested his

innocence and accused the woman of lying. The court officers were

irritated by Heydrich's arrogance. Although they did not make an

official recommendation, Heydrich's dismissal is what the presiding

officers felt was the proper course of action. The matter was passed

back to Admiral Raeder, who dismissed Heydrich from the navy in April

1931. Heydrich was devastated, but he remained engaged to Lina von

Osten. He found himself with no prospects for a career. Heydrich and von Osten married in December 1931.

In 1931, Heinrich Himmler began setting up a counterintelligence division of the SS. Acting on the advice of his associate Karl von Eberstein, who was a friend of Lina von Osten, Himmler interviewed Heydrich. Himmler was impressed and hired him immediately. His pay was 180 reichsmarks per month (40 USD). His NSDAP number was 544,916 and his SS number was 10,120. Heydrich later received a Totenkopfring from Himmler for his service.

On 1 August 1931 Heydrich began his job as chief of the new 'Ic Service' (intelligence service). He set up his office at the Brown House, the Nazi Party headquarters in Munich. By October he had created a network of spies and informers for intelligence gathering purposes and to obtain information to be used as blackmail to further political aims. Information on thousands of people was recorded on index cards stored at the Brown House. To mark the occasion of Heydrich's December wedding, Himmler promoted him to the rank of SS - Sturmbannführer (major). In just over fifteen months, Heydrich had surpassed his former navy rank and was making what was considered a "comfortable" salary.

In

1932 a number of Heydrich's enemies began to spread rumours of his

possible Jewish ancestry. Within the Nazi organisation such innuendo

could be deadly, even for the head of the Reich's counterintelligence

service. An investigation was conducted by Nazi Party racial expert Dr.

Achim Gercke into Heydrich's genealogy. Dr Gercke reported that Heydrich was "... of German origin and free from any colored and Jewish blood". Nevertheless,

Himmler was distressed by the mere suggestion of a man with "tainted"

blood heading his counterintelligence service. In 1942 Himmler told Felix Kersten, his personal masseur, that he had discussed the matter ten years

earlier with Hitler, back when Himmler was head of the Bavarian

political police. Hitler then interviewed Heydrich and found him "a

highly gifted but also very dangerous man, whose gifts the movement had

to retain". Himmler

related to Kersten that Hitler said Heydrich's "non - Aryan origins were

extremely useful; for he would be eternally grateful to us that we had

kept him and not expelled him and would obey blindly". Himmler said to Kersten that Hitler's appraisal turned out to be accurate — that he did obey blindly. Kersten's

recollection of this event and the actions described involving Himmler

and Hitler are "somewhat suspect", having been challenged by historian

Max Williams, who holds it should be "viewed with caution". Peter Longerich also holds that Kersten "cannot in the strict sense be regarded as a reliable source", while Robert Gerwarth regards Kersten's "sensational revelations" as "highly unreliable".

In the summer of 1932, Himmler appointed Heydrich chief of the renamed security service — the Sicherheitsdienst (SD). Heydrich's counterintelligence service grew into an effective machine of terror and intimidation. With Hitler striving for absolute power in Germany, Himmler and Heydrich wished to control the political police forces of all 17 German states, and they began with the state of Bavaria. In 1933, Heydrich gathered some of his men from the SD and together they stormed police headquarters in Munich and took over the police using intimidation tactics. Himmler became the Munich police chief and Heydrich became the commander of Department IV, which controlled the political police.

In 1933, Hitler became Chancellor of Germany, and through a series of decrees became Führer und Reichskanzler (leader and chancellor) of Germany. Originally intended to house political opponents, the first concentration camps were set up in early 1933, and by the end of the year there were over fifty of them.

The Gestapo was originally founded in 1933 as a Prussian police force by Hermann Göring. When Göring transferred full authority over the Gestapo to Himmler in April 1934, it immediately became an instrument of terror under the purview of the SS. Himmler named Heydrich the head of the Gestapo on 22 April 1934.

At this point, the SS was still a part of the Sturmabteilung (SA),

the early Nazi paramilitary organisation. Beginning in April 1934, and

at Hitler's request, Heydrich and Himmler began building a dossier on SA

leader Ernst Röhm in an effort to remove him as a rival for leadership of the party. At Hitler's direction, Heydrich, Himmler, Göring, and Viktor Lutze drew

up lists of those who should be liquidated, starting with seven top SA

officials and including many more. On 30 June 1934, the SS and Gestapo

acted in coordinated mass arrests that continued throughout the weekend.

Röhm was shot without trial, along with the leadership of the SA. This Nazi purge became known as the Night of the Long Knives.

Up to 200 people were killed in the purge. Lutze was appointed new head

of the SA, and it was converted into a sports and training

organization.

With the SA out of the way, Heydrich began building the Gestapo into an instrument of fear. He improved his index card system, creating categories of offenders, and using color coded cards. The Gestapo had the authority to arrest citizens on the suspicion that they might commit a crime, and the definition of a crime was at their discretion. The Gestapo Law, passed in 1936, gave the police force the right to act outside the law. This led to the sweeping use of Schutzhaft — "protective custody", a euphemism for the power to imprison people without judicial proceedings. The courts were not allowed to investigate or interfere. The Gestapo was considered to be acting legally as long as it was carrying out the will of the leadership. People were arrested arbitrarily, sent to concentration camps, or killed.

Himmler began developing the idea of a Germanic religion and

wanted SS members to leave the church. In early 1936, Heydrich left the

Catholic Church. His wife, Lina, had already left the church the year

before. Heydrich not only felt he could no longer be a member, but came

to consider the political power (and influence) of the church a danger

to the state.

On 17 June 1936 all police forces throughout Germany were united, with Himmler as the chief. On 26 June, Himmler reorganised the police into two groups: the Ordnungspolizei (Orpo), which consisted of the national uniformed police and the municipal police, and the Sicherheitspolizei (SiPo), which consisted of the Gestapo and the Kripo or Kriminalpolizei (criminal police). At that point, Heydrich was head of the SiPo and SD. Heinrich Müller was the chief of operations of the Gestapo.

Heydrich was assigned to help organise the 1936 Summer Olympics, held in Berlin. The games were used to promote the propaganda aims of the Nazi regime. Goodwill ambassadors were sent to countries that were considering a boycott. Anti - Jewish violence was forbidden for the duration, and news stands were required to stop displaying copies of Der Stuermer. For his part in the success of the Games, Heydrich was awarded the Deutsches Olympiaehrenzeichen or German Olympic Games Decoration (First Class).

In mid 1939 Heydrich created the Stiftung Nordhav Foundation to obtain real estate for use of the SS and Security Police as guest houses and vacation spots. The Wannsee Villa, which the Stiftung Nordhav acquired in November 1940, was the site of the Wannsee Conference (20 January 1942), a meeting Heydrich held with senior officials of the Nazi regime to formalize plans for the deportation and extermination of all Jews in German occupied territory, and in countries not yet conquered. This action was to be coordinated among the representatives from the Nazi state agencies present at the meeting.

On 27 September 1939 the SD and SiPo (made up of the Gestapo and the Kripo) were folded into the new Reich Main Security Office or SS - Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA), which was placed under Heydrich's control. The title of "Chef der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD" (Chief of the Security Police and SD) or CSSD was conferred on Heydrich on October 1. Heydrich became the President of Interpol on 24 August 1940, and its headquarters was transferred to Berlin. He was promoted to SS - Obergruppenführer und General der Polizei on 24 September 1941.

In 1936, the SD received information that a top ranking Soviet officer was plotting to overthrow Joseph Stalin. Sensing an opportunity to strike a blow at both the Soviet Army as well as Admiral Canaris of the German Abwehr, Heydrich decided the Russian officers should be "unmasked". Heydrich discussed the matter with Himmler and both in turn brought it to the attention of Hitler. Unknown to Heydrich, the "information" that he received about the plot was actually initiated by Stalin himself, in an attempt to make his purges of the Red Army high command believable. Stalin ordered one of his best NKVD agents, General Nikolai Skoblin, to pass Heydrich the false information suggesting a plot against Stalin by Marshall Mikhail Tukhachevsky and other Soviet generals. Heydrich received approval from Hitler to act immediately on the information. Heydrich's SD forged a series of documents and correspondence implicating Tukhachevsky and other Red Army commanders. The material was delivered to the NKVD. The Great Purge of the Red Army followed upon orders of Stalin. While Heydrich believed they had successfully deluded Stalin into executing or dismissing some 35,000 of his officer corps, the importance of Heydrich's part is a matter of speculation and conjecture. The forged documents were not used by Soviet military prosecutors against the generals in their secret trial, which instead relied on false confessions extorted or beaten out of the defendants.

By

late 1940, German armies had swept through most of Western Europe. In

1941, Heydrich's SD was given the responsibility of carrying out the Nacht und Nebel (Night

and Fog) decree, designed to "seize persons endangering German

security". According to the decree, suspects had to be arrested in a

maximally discreet way "under the cover of night and fog". People

disappeared without a trace and no one was told of their whereabouts or their eventual fate. For each prisoner, the SD was required to fill out a questionnaire that

listed their personal information, their country of origin and the

details of their crimes against the Reich. This questionnaire was to be

put into an envelope inscribed with a seal that read "Nacht und Nebel"

and submitted to the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA). In the WVHA "Central

Inmate File", as in many camp files, these prisoners would be given a

special "covert prisoner" code, as opposed to the code for POW, Felon,

Jew, Gypsy, etc. This

decree remained in effect after Heydrich's death. The exact number of

people who vanished in the name of the decree has never been positively

established, but it is estimated to be roughly 7,000.

On 27 September 1941 Heydrich was appointed Deputy Reich Protector of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (the part of Czechoslovakia incorporated into the Reich on 15 March 1939). The Reich Protector, Konstantin von Neurath, remained titular Protector, but was sent on "leave", and Heydrich assumed effective government of the territory, as Hitler, Himmler, and Heydrich felt Neurath's "soft approach" to the Czechs had promoted anti - German sentiment and encouraged anti - German resistance by strikes and sabotage. Heydrich told his aides upon his appointment, "We will Germanize the Czech vermin."

Heydrich came to Prague to

enforce policy, fight resistance to the Nazi regime, and keep up

production quotas of Czech motors and arms that were "extremely important to the German war effort". Heydrich

viewed the area as a bulwark of Germandom and condemned the "stabs in

the back" by the Czech resistance. To realize his goals Heydrich

demanded racial classification of those who could and could not be Germanized. He explained, " ... making this Czech garbage into Germans must give way to methods based on racist thought". Heydrich

started his rule by terrorizing the population: within three days of

his arrival in Prague, 92 people were executed, with their names

appearing on posters throughout the occupied region. Almost all avenues by which Czechs could act Czech in public were closed. According

to Heydrich's estimate between 4,000 and 5,000 people had been arrested

by February 1942. Those who were not executed were sent to Mauthausen - Gusen concentration camp, where only four per cent of Czech prisoners survived the war. In

March 1942, further sweeps against Czech cultural and patriotic

organizations, military, and intelligentsia resulted in the practical

paralysis of Czech resistance. Although small disorganized cells of Central Leadership of Home Resistance (Ústřední vedení odboje domácího, ÚVOD) survived, only communist resistance was able to function in a more coordinated form (although it also suffered arrests). The

terror also served to paralyze resistance in society, with public and

widespread reprisals against any action resisting the German rule. Heydrich's brutal policies during that time quickly earned him the nickname "the Butcher of Prague".

As the Acting Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia, Heydrich applied carrot - and - stick methods. Labor was reorganized on the basis of the German Labor Front. Heydrich used equipment confiscated from the Czech organization Sokol to organize events for workers. The black market was suppressed, with food given out in worker cafeterias. Food rations and free shoes were given out, pensions were increased, and (for some time) free Saturdays were introduced. Unemployment insurance was established for the first time. Those associated with the resistance movement or the black market were tortured or executed. Heydrich described those harshly dealt with as "economic criminals" and "enemies of the people" in the press, which helped gain him support. Conditions in Prague and the rest of the Czech lands were relatively peaceful under Heydrich, and industrial output increased. Still, those measures could not hide shortages and increasing inflation, and reports grew of growing discontent.

Despite public displays of goodwill towards the Czechs, privately Heydrich made no illusions as to his eventual goal: "This entire area will one day be definitely German, and the Czechs have nothing to expect here". Eventually up to two - thirds of Czechs were to be either be removed to regions of Russia or exterminated after Nazi Germany won the war. Bohemia and Moravia were to be annexed directly into the German Reich.

The Czech workforce was exploited as conscripted labor by the Nazis. More than 100,000 workers were removed from "unsuitable" jobs and conscripted by the Ministry of Labor; by December 1941, Czechs could be called to work anywhere within the Reich. Between April and November 1942, 79,000 Czech workers were taken in this manner for work within Nazi Germany. Also in February 1942, the work day was increased from eight hours to twelve.

Heydrich

was, for all intents and purposes, military dictator of Bohemia and

Moravia. His changes to the government's structure left President Emil Hacha and

his cabinet virtually powerless. He often drove alone in a car with an

open roof — a show of his confidence in the occupation forces and in the effectiveness of his government.

In London, the Czechoslovak government - in - exile resolved to kill Heydrich. Jan Kubiš and Jozef Gabčík were chosen for the operation. After receiving training from the British Special Operations Executive (SOE), they returned to the Protectorate by parachute on 28 December 1941, dropped from a Handley Page Halifax. They lived in hiding, preparing for the assassination attempt.

On 27 May 1942 Heydrich was scheduled to attend a meeting with Hitler in Berlin. German documents suggest that Hitler intended to transfer Heydrich to German occupied France, where the French resistance had started to gain ground. Heydrich would have to pass a section where the Dresden - Prague road merged with a road to the Troja Bridge. The intersection, in the Prague suburb of Libeň, was well suited for the attack because Heydrich's car would have to slow to negotiate a hairpin turn. As the car slowed to take the turn, Gabčík took aim with a Sten sub - machine gun, but it jammed and failed to fire. Instead of ordering his driver to speed away, Heydrich called his car to a halt in an attempt to take on the attackers. Kubiš then threw a bomb (a converted anti - tank mine) at the rear of the car as it was coming to a halt. The explosion wounded Heydrich and Kubiš.