<Back to Index>

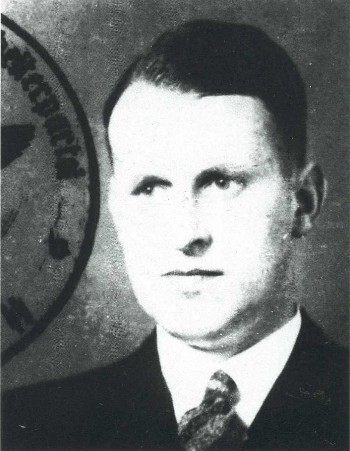

- Commandant of Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen Karl - Otto Koch, 1897

- Engineer of the Crematoria at Auschwitz - Birkenau Hans Friedrich Karl Franz Kammler, 1901

- Chief of the Gestapo Heinrich Müller, 1900

PAGE SPONSOR

Karl-Otto Koch (August 2, 1897 – April 5, 1945), a Standartenführer (Colonel) in the German Schutzstaffel (SS), was the first commandant of the Nazi concentration camps at Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen, and later also served as a commander at the Majdanek concentration camp.

Koch was born in Darmstadt, Grand Duchy of Hesse, on August 2, 1897. His father worked in local registrar's office and died when Karl was only eight years old. After completing elementary school in 1912, Koch began studying business and worked as a messenger and an apprentice in a bookkeeping department in a local factory. In 1916, he volunteered to join the army and fought on the Western Front until he was captured by the British in 1918. Koch spent rest of the war as a POW and returned to Germany in 1919. As a soldier he conducted himself well and was awarded the Iron Cross Second Class, the Observer's Badge and the Wound Badge in Black. Following World War I, Koch worked as an accounting supervisor in a bank and later also in the same role in an insurance company. In 1931, Karl - Otto Koch joined the NSDAP and the Schutzstaffel.

Koch served with several SS - Standarten until June 13, 1935, when he became commander of the Columbia concentration camp in Berlin - Tempelhof. In April 1936 he was assigned to the concentration camp at Esterwegen. Four months later he was moved to Sachsenhausen.

On August 1, 1937, he was given command of the new concentration camp at Buchenwald. He remained at Buchenwald until September 1941, when he was transferred to the Majdanek concentration camp for POWs. That was largely due to an investigation based on allegations of his improper conduct at Buchenwald, which included corruption, fraud, embezzlement, drunkenness, sexual offenses and a murder. Koch commanded the Majdanek camp for only one year; he was relieved from his duties after 86 Soviet POWs escaped from the camp in August 1942. Koch was charged with criminal negligence and transferred to Berlin, where he worked at the SS Personalhauptamt and as a liaison between the SS and the German Post Office.

Koch's actions at Buchenwald first caught the attention of SS - Obergruppenführer Josias, Prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont in

1941. In glancing over the death list of Buchenwald, Josias had

stumbled across the name of Dr. Walter Krämer, a head hospital

orderly at Buchenwald, which he recognized because Krämer had

successfully treated him in the past. Josias investigated the case and

found out that Koch, in a position as the Camp Commandant, had ordered

Krämer and Karl Peixof, a hospital attendant, killed as "political

prisoners" because they had treated him for syphilis and he feared it might be discovered. Waldeck

also received reports that a certain prisoner had been shot while

attempting to escape. By that time, Koch had been transferred to the Majdanek concentration camp in Poland, but his wife, Ilse, was still living at the Commandant's house in Buchenwald. Waldeck ordered a full scale investigation of the camp by Dr. Georg Konrad Morgen, an SS officer who was a judge in a German court. Throughout

the investigation, more of Koch's orders to kill prisoners at the camp

were revealed, as well as embezzlement of property stolen from

prisoners. It

was also discovered that a prisoner who was "shot while trying to

escape" had been told to get water from a well some distance from the

camp, and he was shot from behind. He had also helped treat Koch for

syphilis. A

charge of incitement to murder was lodged by Prince Waldeck and Dr.

Morgen against Koch, to which were later added charges of embezzlement.

Other camp officials were charged, including Koch's wife. The trial

resulted in Koch being sentenced to death for disgracing both himself

and the SS. Koch was executed by firing squad on 5 April 1945, one week before American allied troops arrived to liberate the camp.

Koch first married in 1924 and had one son; however, his marriage ended in divorce 1931, due to his infidelity.

On May 25, 1936 Koch married Ilse Köhler with whom he had a son and two daughters. Köhler later became known as "The Witch of Buchenwald" (Die Hexe von Buchenwald), usually rendered more alliteratively in English as "The Bitch of Buchenwald." When Koch was transferred to Buchenwald, Ilse was appointed an Oberaufseherin (overseer)

by the SS and thus had an active, official role in the atrocities

committed there. There have been many unverified rumors about a

lampshade made from human skin, which has become an often repeated

legend since the war, but no one could testify that they had actually

seen such a thing during Ilse's trial. Acquitted by Morgen, Ilse Koch was sentenced after the war to life in prison. She hanged herself in prison in 1967.

General Dr Ing. Hans (Heinz) Friedrich Karl Franz Kammler (26 August 1901 – May 1945?) was a civil engineer and high ranking officer of the SS. He oversaw SS construction projects, and towards the end of World War II was put in charge of the V-2 missile program.

He is most commonly referred to as Hans Kammler.

Kammler was born in Stettin, Germany (now Szczecin, Poland). In 1919, after volunteering for army service, he served in the extreme right Rossbach Freikorps. From 1919 to 1923, he studied civil engineering at the Technische Hochschule der Freien Stadt Danzig and Munich, and was awarded his Ph.D. in November 1932, following some years of practical work in local building administration.

Kammler joined the NSDAP on 1 March 1932, and held a variety of administrative positions when the Nazi government

came to power in 1933, initially as head of the Aviation Ministry's

building department. He joined the SS (no. 113,619) on 20 May 1933.

Kammler eventually became Oswald Pohl's deputy at the SS - Wirtschafts - Verwaltungshauptamt (WVHA), which oversaw Amtsgruppe D (Amt D), the Administration of the concentration camp system, and was also Chief of Amt C, which designed and constructed all of the concentration and extermination camps. In this latter capacity he oversaw the installation of cremation facilities at Auschwitz - Birkenau, as part of the camp's conversion to an extermination camp.

Following the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943, Heinrich Himmler assigned him to oversee the demolition of the ghetto in retaliation.

Kammler was also charged with constructing facilities for various secret weapons projects, including manufacturing plants and test stands for the Messerschmitt Me 262 and V-2. Following the Allied bombing raids on Peenemünde in Operation Hydra in August 1943, Kammler was assigned to moving these production facilities underground, which resulted in the Mittelwerk facility and its attendant concentration camp complex, Mittelbau - Dora, which housed slave labor for constructing the factory and working on the production lines. The project was pushed ahead under enormous time pressures despite the consequences for the slave laborers employed on it. Kammler's motto at the time was reportedly, "Don't worry about the victims. The work must proceed ahead in the shortest time possible".

Albert Speer made Kammler his representative for "special construction tasks", expecting that Kammler would commit himself to working in harmony with the ministry's main construction committee. But in March 1944 Kammler had Goering appoint him as his delegate for"special buildings" under the fighter aircraft program, which made him one of the war economy's most important managers, and robbed Speer of much of his influence.

In 1944, Himmler convinced Adolf Hitler to put the V-2 project directly under SS control, and on 8 August Kammler replaced Walter Dornberger as its director. From January 1945, Kammler was appointed head of all missile projects and in April 1945 was created "Fuehrer's general plenipotentiary for jet aircraft" by Hitler.

In

March 1945, as US forces were advancing through Germany, the slave

workers housed in the Dora - Mittelbau concentration camp were to be

executed as security risks. It is believed that the order for their

murder was received by Kammler, but he did not comply with it.

There are different accounts of Kammler's death:

- That he committed suicide with a cyanide capsule on 7 May 1945.

- That he shot himself in the head on 9 May 1945.

- That he asked his aide Zeuner to shoot him.

- That he was shot by his aide - de - camp in Prague.

- That the Soviets executed Kammler along with 200 other SS soldiers

- That he died in the USA many years after the war.

On 9 July 1945 Kammler's widow petitioned to have him declared dead as of 9 May 1945, adducing a sworn statement by Kammler's driver, Kurt Preuk, according to which Preuk had personally seen "the corpse of Kammler and been present at his burial" on 9 May 1945. The District Court of Berlin - Charlottenburg ruled on 7 September 1948 that his death was officially established as 9 May 1945.

In a later sworn statement on 16 October 1959, Preuk stated that Kammler's date of death was "about 10 May 1945", but that he did not know the cause of death. However, it must be recognized that many ex Nazis made many sworn statements, to suit many ends. On 7 September 1965, Heinz Zeuner (a wartime aide of Kammler's), stated that Kammler had died on 7 May 1945 and that his corpse had been observed by Zeuner, Preuk and others. All the eyewitnesses consulted were certain that the cause of death was cyanide poisoning. In addition to testifying to Kammler's suicide by cyanide, Zeuner also claimed earlier that Kammler had asked Zeuner to shoot him. However, doubt has been cast on Zeuner's evidence since he is reported to have told an earlier denazification hearing in February 1948 that he was already in US custody on 2 May 1945.. Zeuner's evidence in several sworn statements has subsequently been shown to conflict directly with declassified records.

In their accounts of Kammler's movements Preuk and Zeuner claimed that he left Linderhof near Oberammergau on 28 April 1945 for a tank conference at Salzburg and then went to Ebensee (where tank tracks were manufactured). According to Preuk and Zeuner he then traveled back from Ebensee to visit his wife in the Tyrol region, when he gave her two cyanide tablets. The next day, 5 May, he is said to have departed Tyrol for Prague.

However, Preuk and Zeuner's testimony clashes with the known movements of US Divisions throughout Austria in May 1945. By 4 May 1945 the US 103rd Infantry was already at Innsbruck, preventing Kammler from traveling from Ebensee to Tyrol. The US 88th Infantry division had arrived from Italy cutting off any route to the Tyrol from the south while the US 44th Infantry Division established a command post at Imst in Tyrol on 4 May 1945 and together with the 103rd entirely controlled the Tyrol region preventing Kammler from visiting his wife. Preuk is quite clear that they drove everywhere so that it would have been impossible to bypass US checkpoints.

A further complication is that the 80th Infantry Division reached Ebensee on 4 May 1945, and the concentration camp itself was liberated by two M-18 tank destroyers of the US 80th Division at 2.50pm on 5 May 1945. This would have made it highly likely that Kammler would have been apprehended by US forces.

Author Bernd Ruland, in his 1969 book Wernher von Braun: Mein Leben fur die Raumfahrt, reports an altogether different account of Kammler's death. According to Ruland, Kammler arrived in Prague by aircraft on 4 May 1945, following which he and 21 SS men defended a bunker against an attack by more than 500 Czech resistance fighters on 9 May. During the attack, Kammler's aide - de - camp Sturmbannfuehrer Starck shot Kammler to avoid him falling into enemy hands. This version can reportedly be traced to Walter Dornberger, who in turn is said to have heard it from eyewitnesses.

In recent years Kammler has become associated with apocryphal Nazi super weapons such as "Die Glocke". The first suggestion along these lines came from author Nick Cook, who in his "The Hunt for Zero Point" (2001) raised the possibility that Kammler was brought to the United States along with other German scientists as part of Operation Paperclip as a result of his supposed involvement in secret German projects. Joseph P. Farrell's "Reich of the Black Sun" (2005) casts further doubt upon the facts surrounding his death, however

Farrell's only source is the book "Blunder! How the U.S. Gave Away Nazi

Supersecrets to Russia" (1985) by self - identified "British Intelligence

agent" Tom Agoston.

Heinrich Müller (born 28 April 1900; date of death unknown, but evidence points to May 1945) was a German police official under both the Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany. He became chief of the Gestapo, the political secret state police of Nazi Germany, and was involved in the planning and execution of the Holocaust. He was known as "Gestapo Müller" to distinguish him from another SS general named Heinrich Müller. He was last seen in the Führerbunker in Berlin on May 1, 1945 and remains the most senior figure of the Nazi regime who was never captured or confirmed to have died.

Müller was born in Munich in Bavaria, the son of working class Catholic parents. After service in the last year of World War I as a pilot for an artillery spotting unit, during which he was decorated several times for bravery (including the Iron Cross1st and 2nd class, Bavarian Military Merit Cross 2nd Class with Swords and Bavarian Pilots Badge), he joined the Bavarian police in 1919, and (although not a member of the Freikorps) was involved in the suppression of the communist risings in the early postwar years. After witnessing the shooting of hostages by the revolutionary "Red Army" in Munich during the Bavarian Soviet Republic, he acquired a lifelong hatred of communism. During the years of the Weimar Republic he ran the political department of the Munich police, and became acquainted with many members of the Nazi Party including Heinrich Himmler, and Reinhard Heydrich, although Müller himself in the Weimar period was generally seen as a supporter of the Bavarian People's Party (which at that time ruled Bavaria). On March 9, 1933, during the Nazi putsch that deposed the Bavarian government of Minister - President Heinrich Held, Müller had advocated to his superiors using force against the Nazis. Ironically, these views aided Müller's rise as it guaranteed the hostility of the Nazis, thereby making Müller very dependent upon the patronage of Reinhard Heydrich, who in turn appreciated Müller's professionalism and skill as a policeman, and was aware of Müller's past, making Müller dependent upon Heydrich's protection.

The historian Richard J. Evans wrote: "Müller was a stickler for duty and discipline, and approached the tasks he was set as if they were military commands. A true workaholic who never took a holiday, Müller was determined to serve the German state, irrespective of what political form it took, and believed that it was everyone's duty, including his own, to obey its dictates without question." Evans also records that Müller was a regime functionary out of ambition, not out a belief in National Socialism:

An internal [Nazi] Party memorandum ... could not understand how "so odious an opponent of the movement" could become head of the Gestapo, especially since he had once referred to Hitler as "an immigrant unemployed house painter" and "an Austrian draft - dodger."

On 4 January 1937, an evaluation by the Nazi Party's Deputy Gauleiter of Munich - Upper Bavaria stated:

| “ |

| ” |

After the Nazis came to power in 1933, Reinhard Heydrich as head of the Security Service (SD) recruited Müller and his staff into his organization. He joined the SS in 1934. By 1936, with Heydrich head of the Gestapo, Müller was its chief of operations. Müller continued to rise quickly through the ranks of the SS: by 1939 he was a Gruppenführer (Lieutenant General). In September 1939, when the Gestapo and other police organizations were consolidated under Heydrich into the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA), Müller was chief of the RSHA "Amt IV" (Office or Dept. 4): the Gestapo. To distinguish him from another SS general named Heinrich Müller (a very common German name), he became known as "Gestapo Müller".

As Gestapo chief of operations and later (after 1939) its chief, Müller played a leading role in the detection and suppression of all forms of resistance to the Nazi regime. Under his leadership, the Gestapo succeeded in infiltrating and to a large extent destroying the underground networks of the Communist Party and the Social Democratic Party by the end of 1935. He was also involved in the regime's policy towards the Jews, although Heinrich Himmler and Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels drove this area of policy. Adolf Eichmann, headed the Gestapo's Office of Resettlement and then its Office of Jewish Affairs (the Amt IV section called Referat IV B4). He was Müller's subordinate. Reinhard Heydrich was Müller's direct superior until his assassination in 1942. For the remainder of the war, Ernst Kaltenbrunner took over as Müller's superior.

During World War II, Müller was heavily involved in espionage and counter - espionage, particularly since the Nazi regime increasingly distrusted the military intelligence service — the Abwehr — which under Admiral Wilhelm Canaris was indeed a hotbed of activity for the German Resistance. In 1942 he successfully infiltrated the "Red Orchestra" network of Soviet spies and used it to feed false information to the Soviet intelligence services.

Müller occupied a position in the Nazi hierarchy between Himmler, the overall head of the Nazi police apparatus and the chief architect of the plan to exterminate the Jews of Europe, and Eichmann, the man entrusted with arranging the deportations of Jews to the eastern ghettos and death camps. Thus, although his chief responsibility was always police work within Germany, he was fully in charge and thus responsible to execute the extermination of the Jews of Europe. During 1941 he dispatched Eichmann on tours of inspection of the occupied Soviet Union, and received detailed reports on the work of the Einsatzgruppen, who killed an estimated 1.4 million Jews in 12 months. In January 1942 he attended the Wannsee Conference at which Heydrich briefed senior officials from a number of government departments of the plan, and at which Eichmann took the minutes.

In May 1942 Heydrich was killed in Prague by Czech agents sent from London. Müller was sent to Prague to head the investigation into "Operation Anthropoid". He succeeded through a combination of bribery and torture in locating the assassins, who killed themselves to avoid capture. Despite this success, his influence within the regime declined somewhat with the loss of his original patron, Heydrich. During 1943 he had differences with Himmler over what to do with the growing evidence of a resistance network within the German state apparatus, particularly the Abwehr and the Foreign Office. In February 1943 he presented Himmler with firm evidence that Canaris was involved with the resistance; however, Himmler told him to drop the case. Offended by this, Müller became an ally of Martin Bormann, the head of the Nazi Party Chancellery, who was Himmler's main rival.

After the assassination attempt against Adolf Hitler on

20 July 1944, Müller was placed in charge of the arrest and

interrogation of all those suspected of involvement in the resistance.

Over 5,000 people were arrested and about 200 executed, including

Canaris. In the last months of the war Müller remained at his post,

apparently still confident of a German victory — he told one of his

officers in December 1944 that the Ardennes offensive would result in the recapture of Paris. In April 1945 he was among the last group of Nazi loyalists assembled in the Führerbunker in central Berlin as the Red Army fought its way into the city. One of his last tasks was the sharp interrogation of Hermann Fegelein in the cellar of the Church of the Trinity.

Fegelein was Himmler's liaison officer to Hitler and was shot after

Hitler had Himmler expelled from his posts for negotiating with the

western allies behind Hitler's back.

Müller was last seen in the bunker on the evening of 1 May 1945, the day after Hitler's suicide. Hans Baur, Hitler's pilot, later quoted Müller as saying, "We know the Russian methods exactly. I haven't the faintest intention of being taken prisoner by the Russians." From that day onwards, no trace of him has ever been found. He is the most senior member of the Nazi regime whose fate remains a mystery. Possible explanations for his disappearance include:

- That he was killed, or killed himself, during the chaos of the fall of Berlin, and that his body was never found.

- That he escaped from Berlin and made his way to a safe location, possibly in South America, where he lived the rest of his life undetected, and that his identity was not disclosed even after his death.

- That he was recruited and given a new identity by either the United States or the Soviet Union, and employed by them during the Cold War, and that this has never been disclosed.

The Central Intelligence Agency's file on Müller was released under the Freedom of Information Act in 2001, and documents several unsuccessful attempts by U.S. agencies to find Müller. The U.S. National Archives commentary on the file concludes: "Though inconclusive on Müller's ultimate fate, the file is very clear on one point. The Central Intelligence Agency and its predecessors did not know Müller's whereabouts at any point after the war. In other words, the CIA was never in contact with Müller."

The CIA file shows that an extensive search was made for Müller, among many other wanted Nazi officials, in the months after the German surrender. The search was led by the counterespionage branch of the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (forerunner of the CIA). The search was complicated by the fact that "Heinrich Müller" is a very common German name. The U.S. National Archives comment: "By the end of 1945, American and British occupation forces had gathered information on numerous Heinrich Müllers, all of whom had different birth dates, physical characteristics and job histories... Part of the problem stemmed from the fact that some of these Müllers, including Gestapo Müller, did not appear to have middle names. An additional source of confusion was that there were two different SS Generals named Heinrich Müller."

The U.S. was still looking for Müller in 1947, when agents searched the home of his wartime mistress Anna Schmid, but found nothing suggesting that he was still alive. With the onset of the Cold War and the shift of priorities to meeting the challenge of the Soviet Union, interest in pursuing missing Nazis declined. By this time the conclusion seems to have been reached that Müller was most likely dead. The Royal Air Force Special Investigation Branch also had an interest in Müller with regards to the Stalag Luft III murders, for which he was presumed to have responsibility given his position in the Gestapo.

The seizure in 1960 and subsequent trial in Israel of Adolf Eichmann sparked new interest in Müller's whereabouts. Although Eichmann revealed no specific information, he told his Israeli interrogators that he believed that Müller was still alive. This prompted the West German office in charge of the prosecution of war criminals to launch a new investigation. The West Germans investigated the possibility that Müller was working for the Soviet Union, but gained no definite information. They placed his family and his former secretary under surveillance in case he was corresponding with them.

In 1967 in Panama City, Francis William Keith was accused of being Heinrich Müller, the former head of the Gestapo. West German diplomats pressed Panama to extradite him to Berlin for trial. German prosecutors said Mrs. Sophie Müller, 64, identified the man as her husband. However he was released once fingerprints revealed he was in fact not Müller.

The West Germans investigated several reports of Müller's body being found and buried in the days after the fall of Berlin. None of the sources for these reports were wholly reliable; the reports were contradictory, and it was not possible to confirm any of them. The most interesting of these came from Walter Lüders, a former member of the Volkssturm, who said that he had been part of a burial unit which had found the body of an SS General in the garden of the Reich Chancellery, with the identity papers of Heinrich Müller. The body had been buried, Lüders said, in a mass grave at the old Jewish Cemetery on Grosse Hamburger Strasse in the Soviet Sector. Since this location was in East Berlin in 1961, this gravesite could not be investigated, nor has there been any attempt to excavate this gravesite since the reunification of Germany in 1990.

The CIA also conducted an investigation into Müller's disappearance in the 1960s, prompted by the defection to the West of Lieutenant - Colonel Michael Goleniewski, the Deputy Chief of Polish Military Counter Intelligence. Goleniewski had worked as an interrogator of captured German officials from 1948 to 1952. He did not claim to have met Müller, but said he had heard from his Soviet supervisors that sometime between 1950 and 1952 the Soviets had picked up Müller and taken him to Moscow. The CIA tried to track down the men Goleniewski named as having worked with Müller in Moscow, but were unable to confirm his story, which was in any case no more than hearsay. Israel also continued to pursue Müller: in 1967 two Israeli operatives were caught by West German police attempting to break into the Munich apartment of Müller's wife.

The CIA investigation concluded: "There is little room for doubt that the Soviet and Czech [intelligence] services circulated rumors to the effect that Müller had escaped to the West... to offset the charges that the Soviets had sheltered the criminal... There are strong indications but no proof that Müller collaborated with [the Soviets]. There are also strong indications but no proof that Müller died [in Berlin]." The CIA apparently remained convinced at that time that if Müller had survived the war, he was being harbored within the Soviet Union. But when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 and the Soviet archives were opened, no evidence to support this contention emerged. By the 1990s it was in any case increasingly unlikely that Müller, who was born in 1900, was alive even if he had survived.

The U.S. National Archives commentary concludes: "More information about Müller's fate might still emerge from still secret files of the former Soviet Union. The CIA file, by itself, does not permit definitive conclusions. Taking into account the currently available records, the authors of this report conclude that Müller most likely died in Berlin in early May 1945."