<Back to Index>

- Statesman and Orator Antiphon (Αντιφών), 480 B.C.

PAGE SPONSOR

Antiphon the Sophist lived in Athens probably in the last two decades of the 5th century BC. There is an ongoing controversy over whether he is one and the same with Antiphon (Ἀντιφῶν) of the Athenian deme Rhamnus in Attica (480 – 411 BC), the earliest of the ten Attic orators. For the purposes of this article, they will be treated as distinct persons.

Antiphon of Rhamnus was a statesman who took up rhetoric as a profession. He was active in political affairs in Athens, and, as a zealous supporter of the oligarchical party, was largely responsible for the establishment of the Four Hundred in 411 (Theramenes); upon restoration of the democracy shortly afterwards, he was accused of treason and condemned to death. Thucydides famously characterized Antiphon's skills, influence, and reputation:

| “ | ... He who concerted the whole affair [of the 411 coup], and prepared the way for the catastrophe, and who had given the greatest thought to the matter, was Antiphon, one of the best men of his day in Athens; who, with a head to contrive measures and a tongue to recommend them, did not willingly come forward in the assembly or upon any public scene, being ill - looked upon by the multitude owing to his reputation for cleverness; and who yet was the one man best able to aid in the courts, or before the assembly, the suitors who required his opinion. Indeed, when he was afterwards himself tried for his life on the charge of having been concerned in setting up this very government, when the Four Hundred were overthrown and hardly dealt with by the commons, he made what would seem to be the best defense of any known up to my time. | ” |

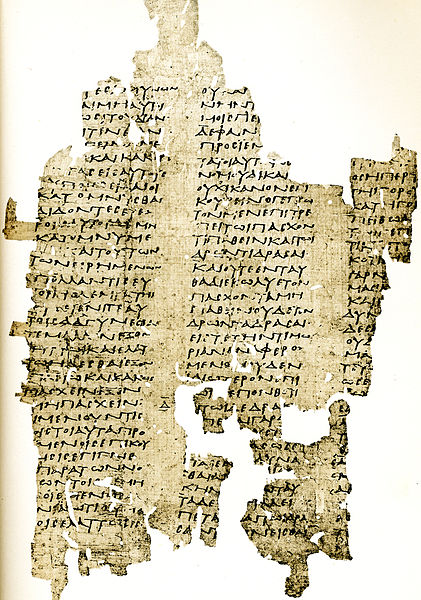

Antiphon may be regarded as the founder of political oratory, but he never addressed the people himself except on the occasion of his trial. Fragments of his speech then, delivered in defense of his policy (called Περὶ μεταστάσεως) have been edited by J. Nicole (1907) from an Egyptian papyrus.

His chief business was that of a logographer (λογογράφος),

that is a professional speech writer. He wrote for those who felt

incompetent to conduct their own cases — all disputants were obliged to

do so — without expert assistance. Fifteen of Antiphon's speeches are

extant: twelve are mere school exercises on fictitious cases, divided

into tetralogies,

each comprising two speeches for prosecution and defense — accusation,

defense, reply, counter - reply; three refer to actual legal processes. All

deal with cases of homicide (φονικαὶ δίκαι). Antiphon is also said to have composed a Τεχνη or art of Rhetoric.

A treatise known as On Truth, of which only fragments survive, is attributed to Antiphon the Sophist. It is of great value to political theory, as it appears to be a precursor to natural rights theory. The views expressed in it suggest its author could not be the same person as Antiphon of Rhamnus, since it was interpreted as affirming strong egalitarian and libertarian principles appropriate to a democracy - but antithetical to the oligarchical views of one who was instrumental in the anti - democratic coup of 411 like Antiphon of Rhamnus. It is been argued that that interpretation has become obsolete in light of a new fragment of text from On Truth discovered in 1984. New evidence supposedly rules out an egalitarian interpretation of the text. However, that argument cannot withstand the actual text of the surviving fragments of "On Truth," which specifically attacks class and national distinctions as being based, not on nature, but on conventional prejudice.

- "Those born of illustrious fathers we respect and honor, whereas those who come from an undistinguished house we neither respect nor honor. In this we behave like barbarians towards one another. For by nature we all equally, both barbarians and Greeks, have an entirely similar origin: for it is fitting to fulfill the natural satisfactions which are necessary to all men: all have the ability to fulfill these in the same way, and in all this none of us is different either as barbarian or as Greek; for we all breathe into the air with mouth and nostrils and we all eat with the hands."

The egalitarian thrust of this statement is unmistakable and is in harmony with the Greek tendency to view liberty as requiring equality. Aristotle for one, mentions this as the consensus concerning democracy, that it champions equality as a form of liberty. This conjunction of equality with liberty would apply both to supporters of democracy like Pericles or opponents, like Plato. The following passages confirm the strongly libertarian commitments of Antiphon the Sophist.

On Truth juxtaposes the repressive nature of convention and law (νόμος) with "nature" (φύσις), especially human nature. Nature is envisaged as requiring spontaneity and freedom, in contrast to the often gratuitous restrictions imposed by institutions:

Most of the things which are legally just are [none the less] ... inimical to nature. By law it has been laid down for the eyes what they should see and what they should not see; for the ears what they should hear and they should not hear; for the tongue what it should speak, and what it should not speak; for the hands what they should do and what they should not do ... and for the mind what it should desire, and what it should not desire.

Repression means pain, whereas it is nature (human nature) to shun pain.

Elsewhere, Antiphon wrote: "Life is like a brief vigil, and the duration of life like a single day, as it were, in which having lifted our eyes to the light we give place to other who succeed us." Mario Untersteiner comments: "If death follows according to nature, why torment its opposite, life, which is equally according to nature? By appealing to this tragic law of existence, Antiphon, speaking with the voice of humanity, wishes to shake off everything that can do violence to the individuality of the person."

In his championship of the natural liberty and equality of all men, Antiphon anticipates the natural rights doctrine of Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, and the Declaration of Independence.

Antiphon was also a capable mathematician. Antiphon, alongside his companion Bryson of Heraclea, was the first to give an upper and lower bound for the value of pi by inscribing and then circumscribing a polygon around a circle and finally proceeding to calculate the polygons' areas. This method was applied to the problem of squaring the circle.