<Back to Index>

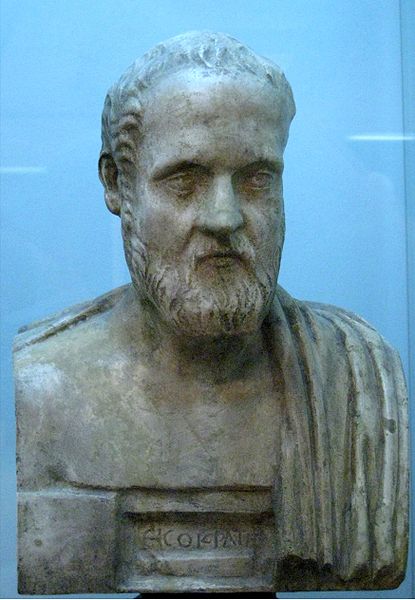

- Rhetorician Isocrates (Ισοκράτης), 436 B.C.

PAGE SPONSOR

Isocrates (Greek: Ἰσοκράτης; 436 – 338 BC), an ancient Greek rhetorician, was one of the ten Attic orators. In his time, he was probably the most influential rhetorician in Greece and made many contributions to rhetoric and education through his teaching and written works.

Greek rhetoric is commonly traced to Corax of Syracuse, who first formulated a set of rhetorical rules in the fifth century BC. His pupil, Tisias, was influential in the development of the rhetoric of the courtroom, and by some accounts was the teacher of Isocrates. Within two generations, rhetoric had become an important art, its growth driven by the social and political changes, such as democracy and the courts of law.

Unlike most rhetoric schools of the times which were taught by itinerant sophists, Isocrates defined himself with his treatise Against the Sophists. This polemic was written to explain and advertise the reasoning and educational principles behind his newly opened school. He promoted his broad based education by speaking against two types of teachers: the Eristics who disputed about theoretical and ethical matters and the Sophists, who taught political debate techniques.

Isocrates was born to a wealthy family in Athens and received a fine education. He was greatly influenced by his sophist teachers, Prodicus and Gorgias, and was also closely acquainted with Socrates. After the Peloponnesian War, Isocrates' family lost its wealth, and Isocrates was forced to earn a living.

Isocrates' professional career is said to have begun as a logographer, or a hired courtroom speech writer. Athenian citizens would not hire lawyers because legal procedure required self representation. Instead they would speak for themselves and hire people like Isocrates to write speeches for them in exchange for a fee. Isocrates had a great talent for this since he lacked confidence in public speaking. His weak voice motivated him to publish pamphlets and although he played no direct part in state affairs, his written speech influenced the public and provided significant insight on large political issues of the fourth century. Around 392 BC he set up his own school of rhetoric, because at the time Athens had no set curriculum for higher education (sophist teachers often traveled), and proved to be not only an influential teacher, but a shrewd businessman. His fees were unusually high, and he accepted no more than nine pupils at a time. Many of them went on to be philosophers, legislators and historians. As a consequence, he amassed a considerable fortune. According to Pliny the Elder (NH VII.30) he could sell a single oration for twenty talents.

Isocrates' program of rhetorical education stressed the ability to use language to address practical problems, and he referred to his teachings as more of a philosophy as opposed to rhetoric. He emphasized that students needed three things to learn: a natural aptitude which was inborn, knowledge training granted by teachers and textbooks and applied practices designed by educators. He also stressed civic education, training students to serve the state. Students would practice composing and delivering speeches on various subjects. He considered natural ability and practice to be more important than rules or principles of rhetoric. Rather than delineating static rules, Isocrates stressed "fitness for the occasion," or kairos (the rhetor's ability to adapt to changing circumstances and situations). His school lasted for over fifty years and taught the basis of liberal arts education as we know it today, including oratory, composition, history, citizenship, culture and morality.

Because of Plato's attacks on the sophists, Isocrates' school of rhetoric and philosophy came to be viewed as unethical and deceitful. Yet many of Plato's criticisms are hard to substantiate in the work of Isocrates, and at the end of his Phaedrus Plato even has Socrates praising Isocrates, though some scholars take this to be sarcastic. Isocrates saw the ideal orator as someone who must not only possess rhetorical gifts, but possess also a wide knowledge of philosophy, science, and the arts. The orator should also represent Greek ideals of freedom, self control, and virtue. In this, he influenced several Roman rhetoricians, such as Cicero and Quintilian, and also had an influence on the idea of liberal education.

On the art of rhetoric, he was also an innovator. He paid closer attention to expression and rhythm far more than any other Greek writer, but because his sentences were so complex and artistic, he often sacrificed clarity to demonstrate his messages.

Of

the 60 orations in his name available in Roman times, 21 were

transmitted by ancient and medieval scribes. Another three orations were

found in a single codex during a 1988 excavation at Kellis, a site in the Dakhla Oasis of Egypt.

We have nine letters in his name, but the authenticity of four has been

questioned. He is said to have compiled a treatise, the Art of Rhetoric, but it has not survived. In addition to the orations, other works include his autobiographical Antidosis and educational texts, such as Against the Sophists.

In Panathenaicus, Isocrates argues with a student about the literacy of the Spartans. In section 250, the student claims that the most intelligent of the Spartans owned copies of and admired some of Isocrates' speeches. The implication is that some Spartans had books, were able to read them and were eager to do so. The Spartans, however, needed an interpreter to clear up any misunderstandings of double meanings which might lie concealed beneath the surface of complicated words. This text indicates that some Spartans were not illiterate. If this speech is taken literally, it would suggest that Spartans could conduct political affairs and that they collected and made use of written works such as speeches. This text is important to scholars' understanding of literacy in Sparta because it indicates that Spartans were able to read and that they often put written documents to use in their public affairs.

"Ἰσοκράτης τῆς παιδείας τὴν ῥίζαν πικρὰν ἔφη, γλυκεῖς δὲ τοὺς καρπούς."

"Isocrates said that the root of education is bitter, but the fruits are sweet."

Progymnasmata of Aphthonios. A similar sentence is found in the Progymnasmata of Libanios.

In Greece there has been, due to the rise of immigration, debate between nationalists and anti - nationalists on what the passage in Panegyricus 50 actually entails. The proposition by antinationalists is that Isocrates said that "A Greek is he who shares our common culture" (meaning Greek culture) and understand from that that he was an early proponent of multiculturalism who wanted barbarians as well as Greeks becoming a part of the Greek ethnic group. On the other hand nationalists refute that with some of them claiming that he in fact meant that "It is a shame that a Greek is considered by some one who shares our culture rather than our common kinship" and paint him as a proto - racist.

Some claim Isocrates was merely making an appeal to unite all Hellenes under the hegemony of Athens (whose culture is implied under the words "our common culture") in a crusade against the Persians rather than their customary fighting against each other. That is Isocrates was referring to Athenian not Greek culture when he said that. In all cases Isocrates was not extending the appellation Hellene to non - Greeks.

However he was also not an early proponent of racism either since he did specifically, in Panegyricus, make an appeal to define the Hellenes as a people sharing a common culture, albeit the Athenian one. This was done in order to boost Athens whose present military weakness meant that its only claim to leadership of the Greeks was its cultural ascendancy.

Nonetheless

Isocrates misinterpretation is not wholly new. Second Sophistic Greeks,

living in a multi - cultural environment had a fresh impetus to

re-interpret him and apply his words, if not spirit, to their time.

τοσοῦτον

δ' ἀπολέλοιπεν ἡ πόλις ἡμῶν περὶ τὸ φρονεῖν καὶ λέγειν τοὺς

ἄλλους ἀνθρώπους, ὥσθ' οἱ ταύτης μαθηταὶ τῶν ἄλλων διδάσκαλοι γεγόνασι,

καὶ τὸ τῶν Ἑλλήνων ὄνομα πεποίηκε μηκέτι τοῦ γένους ἀλλὰ τῆς διανοίας

δοκεῖν εἶναι, καὶ μᾶλλον Ἕλληνας καλεῖσθαι τοὺς τῆς παιδεύσεως τῆς

ἡμετέρας ἢ τοὺς τῆς κοινῆς φύσεως μετέχοντας.

"Our

city of Athens has so far surpassed other men in its wisdom and its

power of expression that its pupils have become the teachers of the

world. It has caused the name of Hellene to be regarded as no longer a

mark of racial origin but of intelligence, so that men are called

Hellenes because they have shared our common education rather than that

they share in our common ethnic origin."