<Back to Index>

- Alchemist Hennig Brandt, 1630

- Chemist and Physicist Robert Boyle, 1627

PAGE SPONSOR

Hennig Brand(t) (c. 1630 – c. 1710) was a merchant and alchemist in Hamburg, Germany. He discovered phosphorus around 1669.

The circumstances of Brand's birth are unknown. Some sources describe his origins as humble and indicate that he had been an apprentice glass maker as a young man. However, correspondence by his second wife Margaretha states that he was of high social standing. In any case he held a post as a junior army officer during the Thirty Years' War and his first wife's dowry was substantial, allowing him to pursue alchemy on leaving the army.

Like other alchemists of the time, Brand searched for the "philosopher's stone", a substance which purportedly transformed base metals (like lead) into gold. By the time his first wife died he had exhausted her money on this pursuit. He then married his second wife Margaretha, a wealthy widow whose financial resources allowed him to continue the search.

Like many before him, he was interested in water (H2O) and tried combining it with various other materials, in hundreds of combinations. He had seen for instance a recipe in a book 400 Auserlensene Chemische Process by F.T. Kessler of Strasbourg for using alum, saltpetre (potassium nitrate) and concentrated urine to turn base metals into silver (a recipe which did not work).

Around 1669 he heated residues from boiled down urine on his furnace until the retort was red hot, where all of a sudden glowing fumes filled it and liquid dripped out, bursting into flames. He could catch the liquid in a jar and cover it, where it solidified and continued to give off a pale green glow. What he collected was phosphorus, which he named from the Greek word for "light - bearing" or "light - bearer."

Phosphorus must have been awe inspiring to an alchemist: it was a product of man, and seeming to glow with a "life force" that did not diminish over time (and did not need re-exposure to light like the previously discovered Bologna stone). Brand kept his discovery secret, as alchemists of the time did, and worked with the phosphorus trying unsuccessfully to use it to produce gold.

His recipe was:

- Boil urine to reduce it to a thick syrup.

- Heat until a red oil distills up from it, and draw that off.

- Allow the remainder to cool, where it consists of a black spongy upper part and a salty lower part.

- Discard the salt, mix the red oil back into the black material.

- Heat that mixture strongly for 16 hours.

- First white fumes come off, then an oil, then phosphorus.

- The phosphorus may be passed into cold water to solidify.

The chemical reaction Brand stumbled on was as follows. Urine contains phosphates PO43-, as sodium phosphate (i.e. with Na+), and various carbon based organics. Under strong heat the oxygens from the phosphate react with carbon to produce carbon monoxide CO, leaving elemental phosphorus P, which comes off as a gas. Phosphorus condenses to a liquid below about 280°C and then solidifies (to the white phosphorus allotrope) below about 44°C (depending on purity). This same essential reaction is still used today (but with mined phosphate ores, coke for carbon, and electric furnaces).

Brand's process yielded far less phosphorus than it could have done.

The salt part he discarded contained most of the phosphate. He used

about 5,500 liters of urine to produce just 120 grams

of phosphorus. If he had ground up the entire residue he could have got

many times more than this (1 liter of adult human urine contains about

1.4g of phosphorus salts, which amounts to around 0.11 grams of pure

white phosphorus).

Robert Boyle, FRS, (25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was a 17th century natural philosopher, chemist, physicist and inventor, also noted for his writings in theology. He has been variously described as Irish, English and Anglo - Irish, his father having come to Ireland from England during the time of the Plantations.

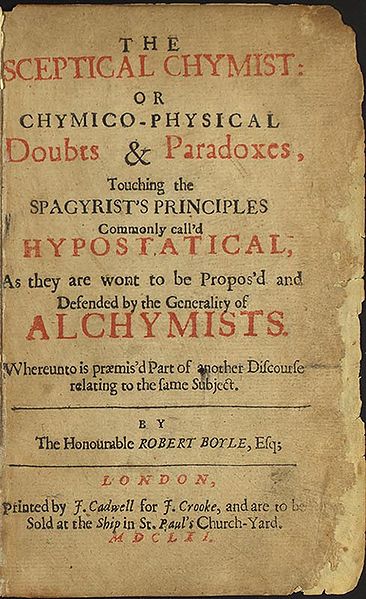

Although his research clearly has its roots in the alchemical tradition, Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the founders of modern chemistry, and one of the pioneers of modern experimental scientific method. He is best known for Boyle's law, which describes the inversely proportional relationship between the absolute pressure and volume of a gas, if the temperature is kept constant within a closed system. Among his works, The Sceptical Chymist is seen as a cornerstone book in the field of chemistry.

Boyle was born in Lismore Castle, in County Waterford, Ireland, the seventh son and fourteenth child of Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork and Catherine Fenton. Richard Boyle arrived in Dublin from England in 1588 during the Tudor plantations of Ireland and obtained an appointment as a deputy escheator. He had amassed enormous landholdings by the time Robert was born. Catherine Fenton was the daughter of English writer Geoffrey Fenton, who was born Dublin in 1539, and Alice Weston, the daughter of Robert Weston, who was born in Lismore in 1541.

As a child, Robert was fostered to a local family, as were his elder brothers. Consequently, the eldest of the Boyle children had sufficient Irish at four years of age to act as a translator for his father. Robert received private tutoring in Latin, Greek and French and when he was eight years old, following the death of his mother, he was sent to Eton College in England. His father's friend, Sir Henry Wotton, was then the provost of the college.

During this time, his father hired a private tutor, Robert Carew, who

had knowledge of Irish, to act as private tutor to his sons in Eton.

However, "only Mr. Robert sometimes desires it [Irish] and is a little

entered in it", but despite the "many reasons" given by Mr. Carew to

turn their attentions to it, "they practice the French and Latin but

they affect not the Irish". After spending over three years at Eton, Robert traveled abroad with a French tutor. They visited Italy in 1641 and remained in Florence during the winter of that year studying the "paradoxes of the great star - gazer" Galileo Galilei, who was elderly but still living in 1641.

Boyle returned to England from Continental Europe in mid 1644 with a keen interest for scientific research. His father had died the previous year and had left him the manor of Stalbridge in Dorset, England, and substantial estates in County Limerick in Ireland that he had acquired. From that time, Robert devoted his life to scientific research and soon took a prominent place in the band of enquirers, known as the "Invisible College", who devoted themselves to the cultivation of the "new philosophy". They met frequently in London, often at Gresham College, and some of the members also had meetings at Oxford.

Having made several visits to his Irish estates beginning in 1647, Robert moved to Ireland in 1652 but became frustrated at his inability to make progress in his chemical work. In one letter, he described Ireland as "a barbarous country where chemical spirits were so misunderstood and chemical instruments so unprocurable that it was hard to have any Hermetic thoughts in it."

In 1654, Boyle left Ireland for Oxford to pursue his work more successfully. An inscription can be found on the wall of University College, Oxford, the High Street at Oxford (now the location of the Shelley Memorial), marking the spot where Cross Hall stood until the early 19th century. It was here that Boyle rented rooms from the wealthy apothecary who owned the Hall.

Reading in 1657 of Otto von Guericke's air pump, he set himself with the assistance of Robert Hooke to devise improvements in its construction, and with the result, the "machina Boyleana" or "Pneumatical Engine", finished in 1659, he began a series of experiments on the properties of air. An account of Boyle's work with the air pump was published in 1660 under the title New Experiments Physico - Mechanicall, Touching the Spring of the Air, and its Effects....

Among the critics of the views put forward in this book was a Jesuit, Francis Line (1595 – 1675), and it was while answering his objections that Boyle made his first mention of the law that the volume of a gas varies inversely to the pressure of the gas, which among English speaking people is usually called Boyle's Law after his name. The person that originally formulated the hypothesis was Henry Power in 1661. Boyle included a reference to a paper written by Power, but mistakenly attributed it to Richard Towneley. In continental Europe the hypothesis is sometimes attributed to Edme Mariotte, although he did not publish it until 1676 and was likely aware of Boyle's work at the time.

In 1663 the Invisible College became the Royal Society of London for the Improvement of Natural Knowledge, and the charter of incorporation granted by Charles II of England, named Boyle a member of the council. In 1680 he was elected president of the society, but declined the honor from a scruple about oaths.

He made a "wish list" of 24 possible inventions which included "The Prolongation of Life", the "Art of Flying", "perpetual light", "making armour light and extremely hard", "A ship to saile with All Winds, and a Ship not to be sunk", "practicable and certain way of finding Longitudes", "potent druggs to alter or Exalt Imagination, Waking, Memory and other functions and appease pain, procure innocent sleep, harmless dreams etc". They are extraordinary because all but a few of the 24 have come true.

It was during his time at Oxford that Boyle was a Chevalier. The Chevaliers are thought to have been established by royal order a few years before Boyle's time at Oxford. The early part of Boyle's residence was marked by the actions of the victorious parliamentarian forces, consequently this period marked the most secretive period of Chevalier movements and thus little is known about Boyle's involvement beyond his membership.

In 1668 he left Oxford for London where he resided at the house of his sister, Lady Ranelagh, in Pall Mall.

In 1689 his health, never very strong, began to fail seriously and he

gradually withdrew from his public engagements, ceasing his

communications to the Royal Society, and advertising his desire to be

excused from receiving guests, "unless upon occasions very

extraordinary", on Tuesday and Friday forenoon, and Wednesday and

Saturday afternoon. In the leisure thus gained he wished to "recruit his

spirits, range his papers", and prepare some important chemical

investigations which he proposed to leave "as a kind of Hermetic legacy

to the studious disciples of that art", but of which he did not make

known the nature. His health became still worse in 1691, and he died on

31 December that year, just a week after that of the sister with whom he

had lived for more than twenty years. Robert Boyle died from paralysis.

He was buried in the churchyard of St Martin in the Fields, his funeral sermon being preached by his friend Bishop Gilbert Burnet. In his will, Boyle endowed a series of Lectures which came to be known as the Boyle Lectures.

Boyle's great merit as a scientific investigator is that he carried out the principles which Francis Bacon espoused in the Novum Organum. Yet he would not avow himself a follower of Bacon, or indeed of any other teacher. On several occasions he mentions that in order to keep his judgment as unprepossessed as might be with any of the modern theories of philosophy, until he was "provided of experiments" to help him judge of them, he refrained from any study of the Atomical and the Cartesian systems, and even of the Novum Organum itself, though he admits to "transiently consulting" them about a few particulars. Nothing was more alien to his mental temperament than the spinning of hypotheses. He regarded the acquisition of knowledge as an end in itself, and in consequence he gained a wider outlook on the aims of scientific inquiry than had been enjoyed by his predecessors for many centuries. This, however, did not mean that he paid no attention to the practical application of science nor that he despised knowledge which tended to use.

Boyle was an alchemist; and believing the transmutation

of metals to be a possibility, he carried out experiments in the hope

of achieving it; and he was instrumental in obtaining the repeal, in

1689, of the statute of Henry IV against multiplying gold and silver. With all the important work he accomplished in physics – the enunciation of Boyle's law,

the discovery of the part taken by air in the propagation of sound, and

investigations on the expansive force of freezing water, on specific gravities and refractive powers, on crystals, on electricity, on color, on hydrostatics, etc. – chemistry was his peculiar and favorite study. His first book on the subject was The Sceptical Chymist, published in 1661, in which he criticized the "experiments whereby vulgar Spagyrists are wont to endeavour to evince their Salt, Sulphur and Mercury

to be the true Principles of Things." For him chemistry was the science

of the composition of substances, not merely an adjunct to the arts of

the alchemist or the physician. He endorsed the view of elements as the

undecomposable constituents of material bodies; and made the distinction

between mixtures and compounds.

He made considerable progress in the technique of detecting their

ingredients, a process which he designated by the term "analysis". He

further supposed that the elements were ultimately composed of particles of various sorts and sizes, into which, however, they were not to be resolved in any known way. He studied the chemistry of combustion and of respiration, and conducted experiments in physiology, where, however, he was hampered by the "tenderness of his nature" which kept him from anatomical dissections, especially vivisections, though he knew them to be "most instructing".

In addition to philosophy, Boyle devoted much time to theology, showing a very decided leaning to the practical side and an indifference to controversial polemics. At the Restoration of the king in 1660 he was favorably received at court, and in 1665 would have received the provostship of Eton College, if he would have taken orders; but this he refused to do on the ground that his writings on religious subjects would have greater weight coming from a layman than a paid minister of the Church.

As a director of the East India Company he spent large sums in promoting the spread of Christianity in the East, contributing liberally to missionary societies and to the expenses of translating the Bible or portions of it into various languages. Boyle supported the policy that the Bible should be available in the vernacular language of the people (in contrast to the Latin only policy of the Roman Catholic Church at the time). An Irish language version of the New Testament was published in 1602 but was rare in Boyle's adult life. In 1680 - 1685 Boyle personally financed the printing of the Bible, both Old and New Testaments, in Irish. In this respect, Boyle's attitude to the Irish language differed from the English Ascendancy class in Ireland at the time, which was generally hostile to the language and largely opposed the use of Irish (not only as a language of religious worship).

Boyle was a believer in monogenism that all races no matter how diverse came from the same source, Adam and Eve. His racial origin views were described as both "disturbing" and "amusing" and were rejected by the scientific community. He studied reported stories of parents giving birth to different colored albinos, he believed that Adam and Eve were originally white and that Caucasians could give birth to different colored races.

In his Will, Boyle provided money for a series of lectures to defend the Christian religion against those he considered "notorious infidels, namely atheists, deists, pagans, Jews and Muslims", with the provision that controversies between Christians were not to be mentioned (Boyle Lectures).