<Back to Index>

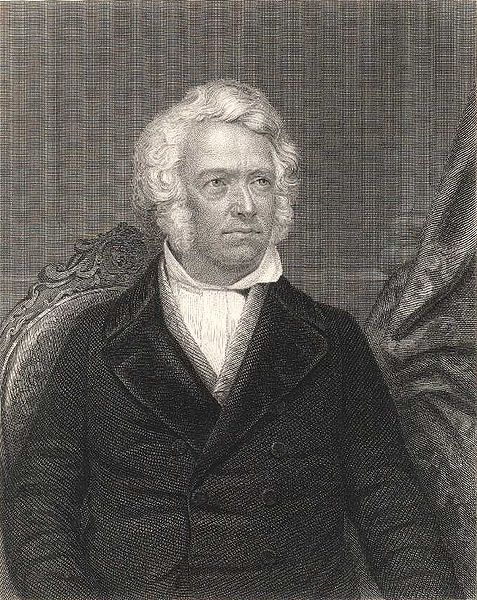

- Chemist Leopold Gmelin, 1788

- Chemist Jean Baptiste André Dumas, 1800

PAGE SPONSOR

Leopold Gmelin (2 August 1788 – 13 April 1853) was a German chemist. Gmelin was professor at the University of Heidelberg and among other things, he worked on the red prussiate and created Gmelin's test.

Gmelin was a son of the physician, botanist and chemist Johann Friedrich Gmelin and his wife Rosine Schott. Due to his family, he came early in contact with medicine and the natural sciences. In 1804 he attended the chemical lectures of his father. In the same year Gmelin moved to Tübingen to work in the family pharmacy. He also studied at the University of Tübingen among other relatives like Ferdinand Gottlieb Gmelin (a cousin) and Carl Friedrich Kielmeyer (husband of a cousin). Supported by Kielmeyer, Gmelin moved to the University of Göttingen in 1805 and later he worked as assistant in the laboratory of Friedrich Stromeyer, under whom he successfully passed his exams in 1809.

Leopold Gmelin returned to Tübingen and again attended the lectures of Ferdinand Gottlieb Gmelin and Carl Friedrich Kielmeyer. In February 1811 Gmelin clashed with the medical student Gutike. Because of an insult he challenged him to a duel, without serious injuries. Because duels were forbidden among students the incident was kept secret at first, but later it came to light. On March 10 Gmelin fled and went to Joseph Franz von Jacquin at the University of Vienna. The focus of his research was on the Black pigment of oxen and calves eyes. The outcome of this work was the subject of Gmelins dissertation. In 1812 he received his doctorate in Göttingen in absentia. Until 1813 Gmelin went on an extensive study trip through Italy. After his return, he began to work as a Privatdozent at Heidelberg University since the winter semester of 1813-14. At first he worked on his Habilitation in Göttingen. On 26 September of the following year he was appointed associate professor in Heidelberg.

In the fall of 1814, he went on another educational trip to Paris to study at the Sorbonne, and remained there until the spring of 1815. Together with his cousin, Christian Gottlob Gmelin he made the acquaintance of René Just Haüy, Joseph Louis Gay - Lussac, Louis Jacques Thénard and Louis Nicolas Vauquelin.

1816 Gmelin married Louise in Heidelberg - Kirchheim, a daughter of the Kirchheimer pastor Johann Conrad Maurer. The lawyer Georg Ludwig von Maurer became his brother - in - law. Together they had three daughters and one son, including Auguste, the future wife of the physician Theodor von Dusch.

When the chemist Martin Heinrich Klaproth died in Berlin in 1817, Gmelin should have succeeded him. However, he refused and became full Professor of Chemistry at Heidelberg University. There, a close cooperation with Friedrich Tiedemann evolved with time. The two published "The digestion after tests" in 1826 and established the basis of the physiological chemistry. In the field of digestive chemistry Gmelin later discovered more components of bile and introduced Gmelin's test. When Friedrich Wöhler worked on complex cyanogen compounds in 1822, Gmelin assisted him and discovered the Red prussiate.

From 1833 to 1838 Gmelin owned a paper mill in the north of Heidelberg situated in Schriesheim. He had taken it over in the hope of profit. However, the work in the mill proved very time- and money-consuming and at the expense of his academic activity.

In 1817 the first volume of Gmelins Handbook of Chemistry was published. Till 1843 it had grown in the fourth edition up to 9 volumes. In this edition Gmelin included the Atomic Theory and devoted much more space to the increasingly important organic chemistry. The terms Ester and Ketone were introduced by Gmelin. Until his death Gmelin worked on the fifth edition of the handbook. He also established the basis for the Gmelin system, which later was named after him, for unambiguous classification of inorganic substances.

At the age of 60 Gmelin suffered a first stroke. Another hit him in

August 1850. In both strokes the right half of his body was affected.

Even though able to recover from the paralysis, but remained

debilitated. In the spring of 1851 Gmelin applied for his retirement,

which was granted him a few months later. In the two following years he

suffered increasingly from the effects of a brain illness. At nearly 65

years Leopold Gmelin died on 13 April 1853 in Heidelberg and was buried

at the Mountain Cemetery in Heidelberg. The grave complex is located in

the department E. There also rests his wife Luise Gmelin and more family

members.

In his works Leopold Gmelin dealt with physiology, mineralogy and chemistry. His experimental work was marked by his very thorough and comprehensive way of working; some literally talent is also attributed to him.

Gmelin's first physiological work was his dissertation on the black pigment of oxen's and calves' eyes, whose coloring principle he tried to fathom. Despite the simplest chemical means he could describe the properties of the pigment and recognized the carbon rightly as the cause of staining. Gmelin's most important physiological work was the 1826 released digestion by experiments, which he made together with Friedrich Tiedemann. The work, which also described many new working techniques, contained groundbreaking insights into the gastric juice, in which they found hydrochloric acid, and bile, in which Gmelin and Tiedemann among others discovered cholesterol and taurine. Introduced by Gmelin, Gmelin's test enabled the detection of bile constituents in the urine of people suffering from jaundice. Furthermore, Gmelin and Tiedemann delivered a new, more refined view of the absorption of nutrients through the gastrointestinal tract; they were the founders of modern physiology.

The mineralogical works of Gmelin were analyses of various minerals, such as the Hauyne with which he made his habilitation in Göttingen, or the Laumontite and the Cordierite. In addition, Gmelin also analyzed mineral waters and in 1825 published the work try of a new chemical mineral system, since he knew that the time's usual division on outer or physical characteristics was inadequate. Leopold Gmelin's mineral system was criticized among experts, but the basic idea of an order based on the chemical composition proved to be useful.

Gmelin released the Handbook of theoretical chemistry, which was continued as the Gmelin Handbook of Inorganic Chemistry until 1997 in about 800 volumes by the Gmelin Institute, and it is continued by the Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker as a database. The manual, even during his lifetime his most important work, was initially intended to be a textbook, which should unite the whole chemical knowledge at that time. Due to the enormous increase in knowledge and the associated development of the handbook into a reference book, Gmelin published a compact textbook of chemistry in 1844. His chemical achievements include the discovery of the Croconic acid; he thus had synthesized the first cyclic organic compound, and the previously mentioned discovery of the red prussiate.

Leopold Gmelin besides also developed a forerunner of the Periodic table and improved chemical equipment.

Jean Baptiste André Dumas (14 July 1800 – 10 April 1884) was a French chemist, best known for his works on organic analysis and synthesis, as well as the determination of atomic weights (relative atomic masses) and molecular weights by measuring vapor densities. He also developed a method for the analysis of nitrogen in compounds.

Dumas was born in Alčs (Gard), and became an apprentice to an apothecary in his native town. In 1816, he moved to Geneva, where he attended lectures by M.A. Pictet in physics, C.G. de la Rive in chemistry, and A.P. de Candolle in botany, and before he had reached his majority, he was engaged with Pierre Prévost in original work on problems of physiological chemistry and even of embryology. In 1822, he moved to Paris, acting on the advice of Alexander von Humboldt, where he became professor of chemistry, initially at the Lyceum, later (1835) at the École polytechnique. He was one of the founders of the École centrale des arts et manufactures (later named École centrale Paris) in 1829.

In 1832 Dumas became a member of the French Academy of Sciences. From 1868 until his death in 1884 he would serve the academy as the permanent secretary for its department of Physical Sciences. In 1838, Dumas was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

After 1848, he exchanged much of his scientific work for ministerial posts under Napoléon III. He became a member of the National Legislative Assembly. He acted as minister of agriculture and commerce for a few months in 1850 - 1851, and subsequently became a senator, president of the municipal council of Paris, and master of the French mint, but his official career came to a sudden end with the fall of the Second Empire.

Dumas was a devout Catholic who would often defend Christian views against critics.

Dumas died at Cannes in 1884, and is buried at the Montparnasse

Cemetery in Paris, in a large tomb near the back wall. His is one of the

72 names inscribed on the Eiffel tower.

Dumas was one of the first to criticize the electro - chemical doctrines of Jöns Jakob Berzelius, which at the time his work began were widely accepted as the true theory of the constitution of compound bodies, and opposed a unitary view to the dualistic conception of the Swedish chemist. In a paper on the atomic theory, published in 1826, he anticipated to a remarkable extent some ideas which are frequently supposed to belong to a later period; and the continuation of these studies led him to the ideas about substitution (metalepsis) which were developed about 1839 into the theory (Older Style Theory) that in organic chemistry there are certain types which remain unchanged even when their hydrogen is replaced by an equivalent quantity of a halide element. Many of his well known researches were carried out in support of these views, one of the most important being that on the action of chlorine on acetic acid to form trichloroacetic acid - a derivative of essentially the same character as the acetic acid itself.

In an 1826 paper, he described his method for ascertaining vapor densities, and the redeterminations which he undertook by its aid of the atomic weights of carbon and oxygen proved the forerunners of a long series which included some thirty of the elements, the results being mostly published in 1858 - 1860. He showed "in all elastic fluids observed under the same conditions, the molecules are placed at equal distances".

In 1833, Dumas developed a method for estimating the amount of nitrogen in an organic compound, founding modern analysis methods.

Dumas showed that kidneys remove urea from the blood.

Dumas established new values for the atomic mass of thirty elements, setting the value for hydrogen to 1.

The classification of organic compounds into homologous series was advanced as one consequence of his researches into the acids generated by the oxidation of the alcohols.