<Back to Index>

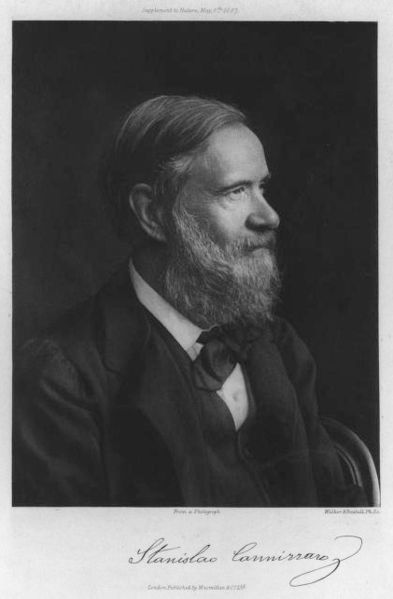

- Chemist Stanislao Cannizzaro, 1826

- Chemist William Odling, 1829

PAGE SPONSOR

Stanislao Cannizzaro, FRS (July 13, 1826 – May 10, 1910) was an Italian chemist. He is remembered today largely for the Cannizzaro reaction and for his influential role in the atomic weight deliberations of the Karlsruhe Congress in 1860.

Cannizzaro was born in Palermo. In 1841, he entered the university there with the intention of making medicine his profession, but he soon turned to the study of chemistry. In 1845 and 1846, he acted as assistant to Raffaele Piria (1815 – 1865), known for his work on salicin, and who was then professor of chemistry at Pisa and subsequently occupied the same position at Turin.

During the Sicilian revolution of independence of 1848, Cannizzaro served as an artillery officer at Messina and was also chosen deputy for Francavilla in the Sicilian parliament; and, after the fall of Messina in September 1848, he was stationed at Taormina. On the collapse of the insurgents, Cannizzaro escaped to Marseille in May 1849, and, after visiting various French towns, reached Paris in October. There he gained an introduction to Michel Eugène Chevreul's laboratory, and in conjunction with F.S. Cloez (1817 – 1883) made his first contribution to chemical research, in 1851, when they prepared cyanamide by the action of ammonia on cyanogen chloride in ethereal solution. In the same year, Cannizzaro accepted an appointment at the National College of Alessandria, Piedmont, as professor of physical chemistry. In Alessandria, he discovered that aromatic aldehydes are decomposed by an alcoholic solution of potassium hydroxide into a mixture of the corresponding acid and alcohol. For example, benzaldehyde decomposes into benzoic acid and benzyl alcohol, the Cannizzaro reaction.

In the autumn of 1855, Cannizzaro became professor of chemistry at the University of Genoa, and, after further professorships at Pisa and Naples, he accepted the chair of inorganic and organic chemistry at Palermo. There, he spent ten years studying aromatic compounds and continuing to work on amines, until in 1871 when he was appointed to the chair of chemistry at the University of Rome.

Apart from his work on organic chemistry, which includes also an investigation of santonin, Cannizzaro rendered great service to chemistry with his 1858 paper Sunto di un corso di Filosofia chimica, or Sketch of a course of chemical philosophy, in which he insisted on the distinction, previously hypothesized by Avogadro, between atomic and molecular weights. Cannizzaro showed how the atomic weights of elements contained in volatile compounds can be deduced from the molecular weights of those compounds, and how the atomic weights of elements of whose compounds the vapor densities are unknown can be determined from a knowledge of their specific heats. For these achievements, of fundamental importance to atomic theory, he was awarded the Copley Medal by the Royal Society in 1891.

In 1871, Cannizzaro's scientific eminence secured him admission to the Italian senate, of which he was vice - president, and as a member of the Council of Public Instruction and in other ways he rendered important services to the cause of scientific education in Italy.

He is best known for his contribution to the then - existing debate

over atoms, molecules, and atomic weights. He championed Amedeo

Avogadro's notion that equal volumes of gas at the same pressure and

temperature held equal numbers of molecules or atoms, and the notion

that equal volumes of gas could be used to calculate atomic weights. In

so doing, Cannizzaro provided a new understanding of chemistry.

William Odling, FRS (5 September 1829, Southwark, London - 17 February 1921, Oxford) was an English chemist who contributed to the development of the periodic table.

In the 1860s Odling, like many chemists, was working towards a periodic table of elements. He was intrigued by atomic weights and the periodic occurrence of chemical properties. William Odling and Lothar Meyer drew up tables similar, but with improvements on, Dmitri Mendeleev's original table. Odling drew up a table of elements using repeating units of seven elements, which bears a striking resemblance to Mendeleev’s first table . The groups are horizontal, the elements are in order of increasing atomic weight and there are vacant slots for undiscovered ones. In addition, Odling overcame the tellurium - iodine problem and he even managed to get thallium, lead, mercury and platinum in the right groups - something that Mendeleev failed to do at his first attempt.

Odling failed to achieve recognition, however, since it is suspected that he, as Secretary of the Chemical Society of London, was instrumental in discrediting John Alexander Reina Newlands'

efforts at getting his own periodic table published. One such

unrecognized aspect was for the suggestion he, Odling, made in a lecture

he gave at the Royal Institution in 1855 entitled The Constitution of Hydrocarbons in which he proposed a methane type for carbon (Proceedings of the Royal Institution, 1855, vol 2, p. 63 - 66). Perhaps influenced by Odling's paper, August Kekulé

made a similar suggestion in 1857, then in a subsequent paper later

that same year proposed that carbon is a tetravalent element.

Odling became a Chemistry Lecturer at St Bartholomew's Hospital Medical School and a Demonstrator at Guy's Hospital Medical School in 1850. Leaving St Bartholomew's in 1868 he became a Fullerian Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution. Later, in 1872 he left the Royal Institution and became a fellow of Worcester College, Oxford, where he stayed till his retirement in 1912.

Odling also served as a fellow (1848 – 1856), Honorary Secretary (1856 – 1869), Vice - President (1869 – 1872) and President (1873 – 1875) of the Chemical Society of London as well as a Censor (1878 – 1880 and 1882 – 1891), Vice - President (1878 – 1880 and 1888 – 1891) and President (1883 – 1888) of the Institute of Chemistry.

In 1859 he was made a fellow of the Royal Society of London and in 1875 he was granted an honorary PhD by Leiden University, Holland.