<Back to Index>

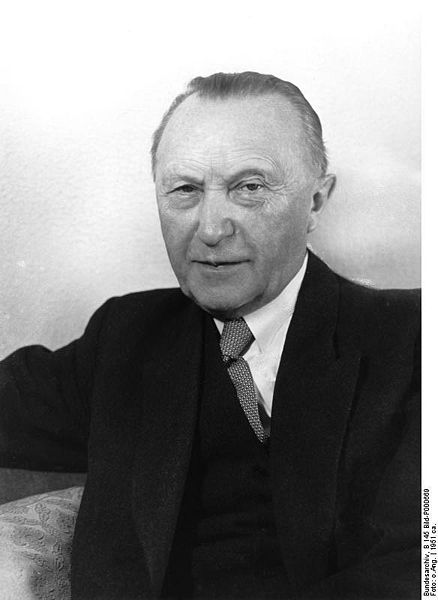

- Chancellor of Germany Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer, 1876

PAGE SPONSOR

Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer (5 January 1876 – 19 April 1967) was a German statesman. As Chancellor of Germany (West Germany) from 1949 to 1963, he led his country from the ruins of World War II to a powerful and prosperous nation that forged close relations with old enemies France and the United States. In his years in power Germany achieved prosperity, democracy, stability and respect. He was the first chancellor (head of government) of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG, called West Germany), 1949 – 63. He was the first leader of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), a coalition of Catholics and Protestants that under his leadership became and has since remained the most dominant in Germany.

Adenauer, dubbed "Der Alte" ("the old one"), belied his age as the oldest elected leader in world history by his intense work habits and his uncanny political instinct. He displayed a strong dedication to a broad vision of democracy, capitalism, and anti - Communism. A shrewd politician, Adenauer was deeply committed to a Western oriented foreign policy and restoring the position of West Germany on the world stage. He worked to restore the West German economy from the destruction in World War II to a central position in Europe, rebuilt its army and came to terms with France, helped make possible Western European unification, opposed rival East Germany, and made his nation a member of NATO and a firm ally of the United States.

A devout Catholic, he was a leading Centre Party politician in the Weimar Republic, he served as Mayor of Cologne (1917 – 1933) and president of the Prussian State Council (1922 – 1933).

Konrad Adenauer was born as the third of five children of Johann Konrad Adenauer (1833 – 1906) and his wife Helene (1849 – 1919) (née Scharfenberg) in Cologne, Rhenish Prussia. His siblings were August (1872 – 1952), Johannes (1873 – 1937), Lilli (1879 – 1950) and Elisabeth, who died shortly after birth in c. 1880. In 1894, he completed his Abitur and started to study law and politics at the universities of Freiburg, Munich and Bonn. He was a member of several Roman Catholic students’ associations under the K.St.V. Arminia Bonn in Bonn. He finished his studies in 1901 and afterwards worked as a lawyer at the court in Cologne.

As a devout Catholic, he joined the Centre Party

in 1906 and was elected to Cologne’s city council in the same year. In

1909, he became Vice - Mayor of Cologne, an industrial metropolis with a

population of 635,000 in 1914. Avoiding the extreme political movements

that attracted so many of his generation, Adenauer was committed to

bourgeois common sense, diligence, order, Christian morals and values,

and was dedicated to rooting out disorder, inefficiency, irrationality

and political immorality. From 1917 to 1933, he served as Mayor of Cologne.

Adenauer headed Cologne during the First World War, working closely with the army to maximize the city's role as a rear base of supply and transportation for the Western Front. He paid special attention to the civilian food supply, as the city financed large warehouses of food that enabled the residents to avoid the worst of the severe shortages that beset most German cities during 1918 – 1919. He set up giant kitchens in working class districts to supply 200,000 rations per day. In the face of the collapse of the old regime and the threat of revolution and widespread disorder in late 1918, Adenauer maintained control in Cologne using his good working relationship with the Social Democrats.

He was mayor during the postwar British occupation. He established a

good working relationship with the British military authorities, using

them to neutralize the workers' and soldiers' council that had become an

alternative base of power for the city's left wing. He flirted with Rhenish separatism (a Rhenish state as part of Germany, but outside Prussia). During the Weimar Republic,

he was president of the Prussian State Council (Preußischer Staatsrat)

from 1922 to 1933, which was the representative of the Prussian cities

and provinces.

Election gains of Nazi party candidates in municipal, state and national elections in 1930 and 1932 were significant. Adenauer, as mayor of Cologne and president of the Prussian State Council, still believed that improvements in the national economy would make his strategy work: ignore the Nazis and concentrate on the Communist threat. He was "surprisingly slow in his reaction" to the Nazi electoral successes, and even when he was already the target of intense personal attacks, he thought that the Nazis should be part of the Prussian and national governments based on election returns. Political maneuverings around the aging President Hindenburg then brought the Nazis to power on January 30, 1933.

By early February Adenauer finally realized that all talk and all attempts at compromise with the Nazis were futile. Cologne's city council and the Prussian parliament had been dissolved; on April 4, 1933 he was officially dismissed as mayor and his bank accounts frozen. "He had no money, no home and no job." After arranging for the safety of his family, he appealed to the abbot of the Benedictine monastery at Maria Laach for a stay of several months. His stay at this abbey, which lengthened to a full year, was cited by the abbot after the war when Adenauer was accused by Heinrich Böll and others of collaboration with the Nazis. According to Albert Speer in his book Spandau: The Secret Diaries, Hitler expressed admiration for Adenauer, noting his civic projects, the building of a road circling the city as a bypass, and a "green belt" of parks. However, both Hitler and Speer concluded that Adenauer's political views and principles made it impossible for him to play any role in Nazi Germany.

He was imprisoned briefly after the Night of the Long Knives in mid 1934. During the next two years, he changed residences often for fear of reprisals against him, while living on the benevolence of friends. With the help of lawyers in August 1937 he was successful in claiming a pension; he received a cash settlement for his house which had been taken over by the city of Cologne, his unpaid mortgage, penalties and taxes were waived. With reasonable financial security he managed to live in seclusion for some years. After the failed assassination attempt on Hitler in 1944, he was imprisoned for a second time as an opponent of the regime. He fell ill and credited Eugen Zander, a former municipal worker in Cologne and communist, with saving his life. Zander, then a section Kapo of a labor camp near Bonn discovered Adenauer's name on a deportation list to the East and managed to get him admitted to a hospital. Adenauer was subsequently rearrested (and so was his wife), but in the absence of any evidence against him was released from prison at Brauweiler in November 1944.

Shortly after the war ended the American occupation forces installed

him again as Mayor of heavily bombed Cologne. After the transfer of the

city into the British zone of occupation the Director of its Military

Government, General Gerald Templer, dismissed Adenauer for what he said was his alleged incompetence.

After his dismissal as Mayor of Cologne, Adenauer devoted himself to building a new political party, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), which he hoped would embrace both Protestants and Roman Catholics in a single party. In January 1946, Adenauer initiated a political meeting of the future CDU in the British zone in his role as doyen (the oldest man in attendance, Alterspräsident) and was informally confirmed as its leader.

Adenauer worked diligently at building up contacts and support in the CDU over the next years, and he sought with varying success to impose his particular ideology on the party. His was an ideology at odds with many in the CDU, who wished to unite socialism and Christianity; Adenauer preferred to stress the dignity of the individual, and he considered both communism and Nazism materialist world views that violated human dignity.

Adenauer's leading role in the CDU of the British zone won him a position at the Parliamentary Council of 1948, called into existence by the Western Allies to draft a constitution for the three western zones of Germany.

He was the chairman of this constitutional convention and vaulted from

this position to being chosen as the first head of government once the

new "Basic Law" had been promulgated in May 1949.

The first election to the Bundestag of West Germany was held on 15 August 1949, with the Christian Democrats emerging as the strongest party. Theodor Heuss was elected the first President of the Republic, and Adenauer was elected Chancellor (head of government) on 16 September 1949 with the support of his own CDU, the Christian Social Union and the liberal Free Democratic Party. At age 73, it was initially thought that he would only be a caretaker chancellor. However, he would go on to hold this post for 14 years, a period which spans most of the preliminary phase of the Cold War. During this period, the post war division of Germany was consolidated with the establishment of two separate German states, the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) and the German Democratic Republic (East Germany).

In the controversial selection for a "provisional capital" of the Federal Republic of Germany Adenauer championed Bonn over Frankfurt am Main. The British had agreed to detach Bonn from their zone of occupation and convert the area to an autonomous region wholly under German sovereignty; the Americans were not prepared to grant the same for Frankfurt.

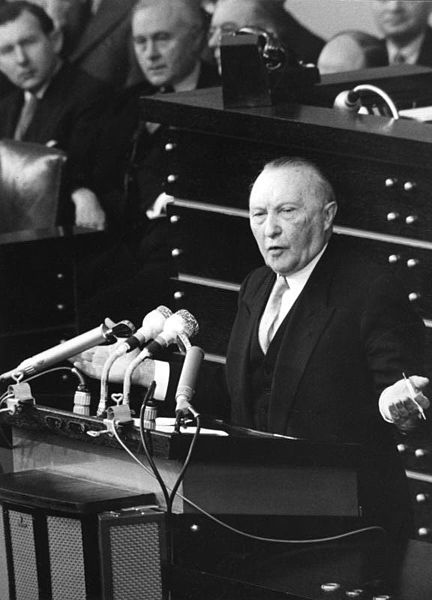

At the Petersberg Agreement in November 1949 he achieved some of the first concessions granted by the Allies, such as a decrease in the number of factories to be dismantled, but in particular his agreement to join the International Authority for the Ruhr led to heavy criticism. In the following debate in parliament Adenauer stated:

- The Allies have told me that dismantling would be stopped only if I satisfy the Allied desire for security, does the Socialist Party want dismantling to go on to the bitter end?

The opposition leader Kurt Schumacher responded by labeling Adenauer "Chancellor of the Allies".

When a rebellion in East Germany

was harshly suppressed by the Red Army in June 1953, Adenauer took full

advantage of the situation and was handily re-elected to a second term

as Chancellor.

The CDU / CSU came up one seat short of an outright majority. Adenauer

could have governed alone without the support of other parties, but

retained the support of nearly all of the parties in the Bundestag that

were to the right of the SPD.

The election of 1957 essentially dealt with national matters. Riding a wave of popularity from the return of the last POWs from Soviet labor camps, as well as an extensive pension reform, Adenauer led the CDU / CSU to the first — and as of 2011, only — outright majority in a free German election.

For a couple of weeks in 1959, Adenauer considered leaving the chancellorship and becoming Federal President. He initially believed that the office could be fulfilled in a more politically active way than president Heuss did. He reconsidered, among other reasons, because he was afraid that Ludwig Erhard would become the new chancellor of whom Adenauer thought little.

The mood had changed by election time in September 1961. Over the course of 1961, Adenauer had his concerns about both the status of Berlin and US leadership confirmed, as the Soviets and East Germans built the Berlin Wall. Adenauer had come into the year distrusting the new US President, John F. Kennedy. He doubted Kennedy's commitment to a free Berlin and a unified Germany and considered him undisciplined and naïve.

For his part, Kennedy thought that Adenauer was a relic of the past, stating "The real trouble is that he is too old and I am too young for us to understand each other." Their strained relationship impeded effective Western action on Berlin during 1961. Adenauer had tarnished his image when he announced he would run for the office of federal president in 1959, only to pull out when he discovered that under the Basic Law, the president had far less power than he did in the Weimar Republic. Additionally, the departing and respected Theodor Heuss had established the precedent that the president be nonpartisan, which clashed with Adenauer's vision. The construction of the Berlin Wall in August 1961 and the sealing of borders by the East Germans made his government look weak. His "reaction was ... lame;" he eventually flew to Berlin, but he appeared to have "lost his once instinctive, ultra - swift power of judgement." After failing to keep their majority in the general election 36 days after the wall went up, the CDU / CSU again needed to include the FDP in a coalition government. To strike a deal, Adenauer was forced to make two concessions: to relinquish the chancellorship before the end of the new term, his fourth, and to replace his foreign minister.

By 1949 the U.S. and Britain agreed that West Germany had to be rearmed

to strengthen the defenses of Western Europe against a possible Soviet

invasion. What was needed was a viable democratic German Army, free of

the militarism and outlook of its wartime predecessor. The idea was that

it would be essential for the defense of Germany and indeed all of

Western Europe. Adenauer was able to overcome grave French objections

and created the non - nuclear "Bundeswehr" based on democratic principles

and practices that met the Allies' criteria.

However, contemporary critics accused Adenauer of cementing the division of Germany, sacrificing reunification and the recovery of territories lost in the westward shift of Poland and the Soviet Union. "In his view, he said with the greatest emphasis, full integration into Western Europe was a precondition of the reunification of Germany." During the Cold War, the United States was "aiming for a West German armed force, after their [U.S.] costly experience in the Korean War," and Adenauer linked this rearmament concept to West German sovereignty and entry into NATO. In 1952, the Stalin Note, as it became known, "caught everybody in the West by surprise." It offered to unify the two German entities into a single, neutral state with its own, non - aligned national army to effect superpower disengagement from Central Europe. Adenauer and his cabinet were unanimous in their rejection of the Stalin overture; they shared the Western Allies’ suspicion about the genuineness of that offer and supported the Allies in their cautious replies.

Adenauer’s flat rejection was, however, out of step with public opinion; he then realized his mistake and he started to ask questions. Critics denounced him for having missed an opportunity for German reunification. The Soviets sent a second note, courteous in tone. Adenauer by then understood that "all opportunity for initiative had passed out of his hands," and the matter was put to rest by the Allies. Given the realities of the Cold War, German reunification and recovery of lost territories in the east were not realistic goals as both of Stalin's notes specified the retention of the existing "Potsdam" - decreed boundaries of Germany. His re-election campaigns centered around the slogan "No Experiments."

As chancellor, Adenauer tended to make most major decisions himself, treating his ministers as mere extensions of his authority. While this tendency decreased under his successors, it established the image of West Germany (and later reunified Germany) as a "chancellor democracy."

The German student movement of the late 1960s was essentially a left wing protest against the conservatism that Adenauer — by then out of office — had personified. Radical student protesters and Marxist groups were further inflamed by strong Anti - Americanism fueled by the Vietnam War and opposition to the conservative Nixon administration.

During the early years of his chancellorship and with a broad consensus within the West German establishment in favor of amnesty and integration, Adenauer pressed for the ending of denazification efforts. The denazification process was viewed by the United States as counterproductive and ineffective, and its demise was not opposed. Adenauer’s intention was to switch government policy to reparations and compensation for the victims of NS rule (Wiedergutmachung), stating that the main culprits had been prosecuted.

As result, Germany started negotiations with Israel for restitution of lost property and the payment of damages to victims of the Nazi persecutions. In the Luxemburger Abkommen, Germany agreed to pay compensation to Israel. Jewish claims were bundled in the Jewish Claims Conference, which represented the Jewish victims of Nazi Germany. Germany then initially paid about 3 billion Mark to Israel and about 450 million to the Claims Conference, although payments continued after that, as new claims were made. Israel was divided in accepting the money.The agreement was condemned by some Israelis as simply an expedient whereby Germany would buy off Jewish survivors to regain credibility on the international stage, and Adenauer was criticized for being too lenient towards politically compromised individuals whose past treatment of Jews was at best questionable. But ultimately the fledgling state under David Ben Gurion agreed to take it, opposed by more radical groups like Irgun, who were against such treaties. Those treaties were cited as a main reason for the assassination attempt by the radical Jewish groups against Adenauer.

For a legal backup, the German German Restitution Laws (Bundesentschädigungsgesetz) were passed in 1956, allowing individuals and other ethnic groups than Jews to lay claims for compensation from the German state, if they were victims of Nazi prosecution. Aside from that, other global treaties for compensation were made with other European states in the following decades, to compensate for the Nazi crimes.

By 1951 laws were passed by the Bundestag ending denazification. Officials were allowed to retake jobs in civil service, with the exception of people assigned to Group I (Major Offenders) and II (Offenders) during the denazification review process. The amnesty legislation had benefited 792,176 people, among them:

- 3,000 functionaries of the SA, the SS, and the Nazi Party who participated in deporting victims to prisons and camps;

- 20,000 other Nazi perpetrators sentenced for "deeds against life" (presumably murder);

- 30,000 sentenced for causing bodily injury;

- 5,200 charged with "crimes and misdemeanors in office."

Adenauer was prepared to tolerate ex - Nazis in his administration provided their membership in the party had been inactive, or necessary for them to keep their job. Despite these claims he nominated people active under Nazi Germany to top ministerial positions, including Hans Globke,

Director of the Federal Chancellory of West Germany between 1953 and

1963 and one of the closest aides to Chancellor Konrad Adenauer. It was a

policy that attracted criticism; however, Adenauer started his

administration from absolute zero, and “it would have been folly to

deprive the fledgling republic of the services of [these civil servants

and professionals] for that reason alone.”

He made it clear for all, if they stepped out of line, they could

expect a case for de - Nazification to be reopened. To construct a

“competent Federal Government effectively from a standing start was one

of the greatest of Adenauer’s formidable achievements.”

Adenauer’s achievements include the establishment of a stable democracy in West Germany and a lasting reconciliation with France, culminating in the Élysée Treaty. His political commitment to the Western powers achieved a limited, but far - reaching sovereignty for West Germany by firmly integrating the country with the emerging Euro - Atlantic community (NATO and the Organisation for European Economic Cooperation). Adenauer is closely linked to the implementation of an enhanced pension system, which ensured unparalleled prosperity for retired people. Along with his Minister for Economic Affairs and successor Ludwig Erhard, the West German model of a "social market economy" (a mixed economy with capitalism moderated by elements of social welfare and Catholic social teaching) allowed for the boom period known as the Wirtschaftswunder ("economic miracle") that produced broad prosperity. The Adenauer era witnessed a dramatic rise in the standard of living of average Germans, with real wages doubling between 1950 and 1963. This rising affluence was accompanied by a 20% fall in working hours during that same period, together with a fall in the unemployment rate from 8% in 1950 to 0.4% in 1965. In addition, an advanced welfare state was established.

Adenauer ensured a truly free and democratic society which had been almost unknown to the German people before — notwithstanding the attempt between 1919 and 1933 (the Weimar Republic) — and which is today not just normal but also deeply integrated into modern German society. He thereby laid the groundwork for Germany to reenter the community of nations and to evolve as a dependable member of the Western world. It can be argued that because of Adenauer’s policies, a later reunification of both German states was possible; and unified Germany has remained a solid partner in the European Union and NATO.

In retrospect, mainly positive assessments of his chancellorship

prevail, not only with the German public, which voted him the "greatest German of all time" in a 2003 television poll,

but even with some of today’s left wing intellectuals, who praise his

unconditional commitment to western style democracy and European

integration.

- Made a historic speech to the Bundestag in September 1951 in which he recognized the obligation of the German government to compensate Israel, as the main representative of the Jewish people, for The Holocaust. This started a process which led to the Bundestag approving a pact between Israel and Germany in 1953 outlining the reparations Germany would pay to Israel.

- Opened diplomatic relations with the USSR, but refused to recognize East Germany and broke off diplomatic relations with countries (e.g., Yugoslavia) that established relations with the East German régime.

- Helped secure the release of the last German prisoners of war in 1955 (Forced labor of Germans in the Soviet Union).

- Reached an agreement for his "nuclear ambitions" with a NATO Military Committee in December 1956 that stipulated West German forces to be "equipped for nuclear warfare." Concluding that the United States would eventually pull out of Western Europe, Adenauer pursued nuclear cooperation with other countries. The French government then proposed that France, West Germany and Italy jointly develop and produce nuclear weapons and delivery systems, and an agreement was signed in April 1958. With the ascendancy of Charles de Gaulle, the agreement for joint production and control was shelved indefinitely. President John F. Kennedy, an ardent foe of nuclear proliferation, considered sales of such weapons moot since "in the event of war the United States would, from the outset, be prepared to defend the Federal Republic." The physicists of the Max Planck Institute for Theoretical Physics at Göttingen and other renowned universities would have had the scientific capability for in-house development, but the will was absent, nor was there public support. With Adenauer’s fourth term election in November 1961 and the end of his chancellorship in sight, his "nuclear ambitions" began to taper off.

- Oversaw the reintegration of the Saarland into West Germany in 1957.

- Briefly considered running for the office of Federal President in 1959. After his reversal he supported the nomination of Heinrich Lübke as the CDU presidential candidate whom he believed weak enough not to interfere with his actions as Federal Chancellor.

For all of his efforts as West Germany's leader, Adenauer was named Time magazine’s Man of the Year in 1953. In 1954, he received the Karlspreis (English: Charlemagne Award), an Award by the German city of Aachen to people who contributed to the European idea, European cooperation and European peace.

In his last years in office, Adenauer used to take a nap after lunch and, when he was traveling abroad and had a public function to attend, he sometimes asked for a bed in a room close to where he was supposed to be speaking, so that he could rest briefly before he appeared.

Adenauer found relaxation and great enjoyment in the Italian game of bocce and spent a great deal of his post political career playing this game. His favorite holiday place to do this was in Cadenabbia, Italy, in a rented villa overlooking Lake Como, which has since been acquired as a conference center by the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, the political foundation established by Adenauer's political party Christian Democratic Union (CDU).

When, in 1967, after his death at the age of 91, Germans were asked

what they admired most about Adenauer, the majority responded that he

had brought home the last German prisoners of war from the USSR, which

had become known as the "Return of the 10,000".

On 27 March 1952, a package addressed to Chancellor Adenauer exploded in the Munich Police Headquarters, killing one Bavarian police officer. Two boys who had been paid to send this package by mail had brought it to the attention of the police. Investigations led to people closely related to the Herut Party and the former Irgun armed organization. The West German government kept all proof under seal in order to prevent antisemitic responses from the German public. Five Israeli suspects identified by French and German investigators were allowed to return to Israel.

One of the participants, Eliezer Sudit, later revealed that the alleged mastermind behind this assassination attempt was Menachem Begin who would later become the Prime Minister of Israel. Begin had been the former commander of Irgun and at that time headed Herut and was a member of the Knesset. His goal was to put pressure on the German government and prevent the signing of the Reparations Agreement between Israel and West Germany, which he vehemently opposed.

David Ben - Gurion, Prime Minister of Israel, appreciated Adenauer’s response in playing down the affair and not pursuing it further, as it would have burdened the relationship between the two new states.

In June 2006 a slightly different version of this story appeared in one of Germany's leading newspapers, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, quoted by The Guardian.

Begin had offered to sell his gold watch as the conspirators ran out of

money. The bomb was hidden in an encyclopedia and it killed a

bomb disposal expert, injuring two others. Adenauer was targeted because of the Reparations Agreement between Israel and West Germany,

signed at that time, which was violently opposed by Begin. Sudit, the

story's source, explained that the "intent was not to hit Adenauer but

to rouse the international media. It was clear to all of us there was no

chance the package would reach Adenauer". The five conspirators were

arrested by the French police, in Paris. They "were [former] members of the ... Irgun" (the organization had been disbanded in 1948, 4 years earlier).

In October 1962, a scandal erupted when police arrested five Der Spiegel journalists, charging them with high treason for publishing a memo detailing weaknesses in the West German armed forces. Adenauer had not initiated the arrests, but initially defended the person responsible, Defense Minister Franz Josef Strauss, and called the Spiegel memo "Abgrund von Landesverrat" (abyss of treason). After public outrage and heavy protests from the coalition partner FDP he dismissed Strauss, but the reputation of Adenauer and his party had already suffered.

Adenauer managed to remain in office for almost another year, but the

scandal increased the pressure he was under to fulfill his promise to

resign before the end of the term. Adenauer was not on good terms with

his economics minister Ludwig Erhard

and tried to block him from the chancellorship. Adenauer failed, and in

October 1963 he turned the office over to Erhard. He did remain

chairman of the CDU until his resignation in December 1966.

Adenauer died on 19 April 1967 in his family home at Rhöndorf. According to his daughter, his last words were "Da jitt et nix zo kriesche!" (Cologne dialect for "There's nothin' to weep about!")

Konrad Adenauer's state funeral in Cologne Cathedral was attended by a large number of world leaders, among them United States President Lyndon B. Johnson. After the Requiem Mass and service, his remains were brought upstream to Rhöndorf on the Rhine aboard Kondor, with Seeadler and Sperber as escorts, three Jaguar class fast attack craft of the German Navy, "past the thousands who stood in silence on both banks of the river." He is interred at the Waldfriedhof [Forest Cemetery] at Rhöndorf.

Adenauer was the main motive for one of the most recent and famous gold

commemorative coins: the Belgian 3 pioneers of the European unification

commemorative coin, minted in 2002. The obverse side shows a portrait

with the names Robert Schuman, Paul-Henri Spaak and Konrad Adenauer.