<Back to Index>

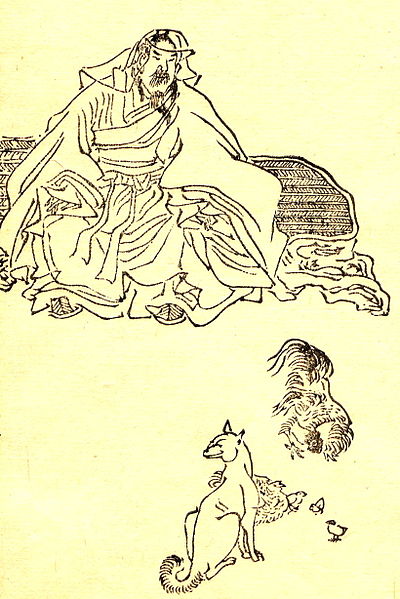

- Writer and Philosopher Ge Hong, 283

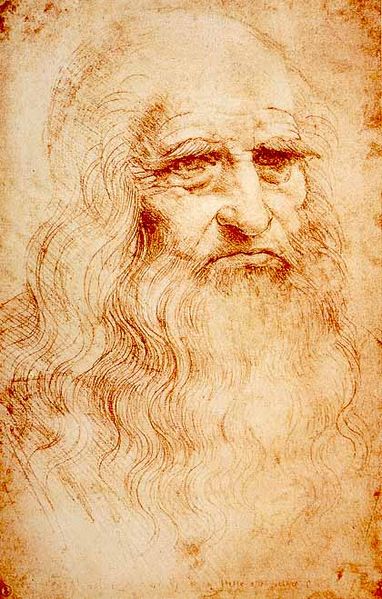

- Polymath Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci, 1452

PAGE SPONSOR

Ge Hong (Chinese: 葛洪; pinyin: Gě Hóng; Wade–Giles: Ko Hung, 283 – 343), courtesy name Zhichuan (稚川), was a minor southern official during the Jìn Dynasty (263 - 420) of China, best known for his interest in Daoism, alchemy and techniques of longevity. Yet religious and esoteric writing represents only a portion of Ge's considerable literary output, which as a whole, spans a broad range of content and genres.

Although a prolific writer of many literary styles, most of Ge's early work, such as rhapsodies (fu), verse (shi), historical commentary and biographies, are now lost. His surviving works consist of one volume of hagiographies, entitled Shenxian zhuan (Traditions of Divine Transcendents); and two volumes of essays and alchemical writing totaling seventy chapters, collectively entitled Baopuzi (抱朴子) or "The Master Who Embraces Simplicity", Ge’s sobriquet. In the Neipian (Inner Chapters) volume of the Baopuzi, Ge vigorously defends the attainability of divine transcendence or "immortality" through alchemy; the Waipian (Outer Chapters) volume is almost entirely given to social and literary criticism.

Most of Ge's surviving work demonstrates the influence of notable essayists and thinkers from the Han

period (206 BC- 220 AD) such as Sima Qian (c. 145 - 90 BC), and Wang

Chong (c. 27 - 97), as well as poets and literati from the post Han era,

such as Ji Kang (223 - 262) and Zuo Si (c. 253 - 309). Modern scholars

have recognized his influence on later writers, such as the Tang dynasty

(618 - 906) poet Li Bai (701 - 762), who was inspired by images of

transcendence and reclusion. Nevertheless, Ge’s work was never enshrined

in famous collections of essays and poetry, such as the Wenxuan (Selections of Refined Literature), as was Ji Kang’s essay, Yang sheng

(Nourishing Life), whose style Ge freely imitated. Reflecting the

complex intellectual landscape of the Jin period, Ge is essential

reading for an understanding of early medieval Chinese religion, culture

and society. Recent scholarly and popular translations of Ge’s writing

into English have ensured his inclusion in the swelling tide of

enthusiasm for esoteric and religious Daoism in the West.

Biographical sources for Ge are varied, but almost all of them are based either in whole or in part upon his autobiographical "Postface to the Outer Chapters". It is nearly impossible to judge the veracity of Ge’s account of his early family history as found in the postface. Following literary convention, he claims that his early ancestors were of a ruling house that adopted the name of their dynasty as a family name. A more recent ancestor who held the post of Regional Inspector of Jingzhou, during the Former Han, resisted the usurpation of the Han dynasty by "the bandit", Wang Mang (33 BC - 22 AD), and was exiled to Langya in modern Shandong province. The sons of this ancestor, Pu Lu and Wen, fought together to assist Emperor Guangwu of Han (reigned 25 - 57) in restoring the Han dynasty. Due to his official status in the government army, Pu Lu received rich rewards and a lofty official appointment while Wen, who followed his older brother into battle as a private soldier, did not. This situation was unacceptable to Pu Lu who, according to Ge’s account, eventually gave away his estate and position to his younger brother and retired south of the Yangtze River to become a farmer in Jurong, located in Jiangsu province, near present day Nanjing.

Ge’s family remained in the south for generations, and occupied official positions in the Kingdom of Wu (220 - 280), which ruled southeastern China after the final dissolution of the Han dynasty in the early 3rd century. According to Ge, his grandfather, Ge Xi, was an erudite scholar who governed several counties in modern Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces, including present day Hangzhou. He eventually rose to the rank of Junior Mentor to the crown prince of Wu, and occupied numerous posts within the central administration.

Ge describes his father, Ge Ti (died 295), in similar, laudatory terms as a scholarly gentleman of model conduct. Ge Ti served in various civil and military positions, and was eventually appointed Governor of Kuaiji prefecture. Around the time of this appointment, the Jin dynasty, which had already succeeded in unifying northern China around 265, invaded Wu under the command of the famous literatus and Jin general, Du Yu (222 - 284). Du Yu would return to the north and write a well known commentary to the Zuo zhuan (Zuo Commentary to the Spring and Autumn Annals) after the conquest of Wu in 280.

The Jin victory changed the fortunes of Ge’s family. Because the Jin

administration attempted to check the power of the southern gentry by

giving them positions of little authority, Ge Ti initially lost prestige

and power under Jin rule. He was appointed to various posts at the Jin

capital of Luoyang,

as well as positions in several counties. Ge Ti’s administrative skills

were eventually rewarded with a promotion, and he died while in office,

serving as the Governor of Shaoling in modern Hunan province, an area of relatively modest size.

Ge was born in 283 in Jurong, just three years after the Jin conquest of Wu. He was the youngest of three sons, but no information exists concerning his older brothers. By his own account, Ge possessed a serious demeanor as a child, declining to play with other children or to participate in activities such as chess, gambling or cock fighting. He was equally uninterested in serious study, and states that his indulgent parents never compelled him to pursue the kind of academic training that was probably expected for the offspring of an influential gentry family. Ge was only twelve years old when his father died in 295, an incident that seems to have inflicted some hardship on his family. He states that he personally engaged in plowing and planting, suffering from cold and hunger. The destruction of his father’s library by soldiers due to civil strife worsened Ge’s plight and, in one colorful passage from his postface, he describes how he used his meager income earned from chopping firewood to underwrite his education. Ge’s claim of extreme poverty is generally regarded as an exaggeration. It has been rightly observed that so distinguished a family, with such a long and prestigious record of government office, would not have declined so quickly into economic ruin.

It is probably true that the death of his father was a blow to Ge’s public aspirations, for it may have meant losing his father’s network of friends and allies that might have helped him find an official position. Several modern scholars have correctly pointed out that ordinary farmers could ill afford such luxuries as books or the leisure time to read them. The possibility that Hong subsidized a broad education with manual labor is remote at best. Regardless, it is not hard to imagine that, upon his father’s death, Ge’s family underwent a period of relative hardship, during which he may have personally supervised the family estate, an activity that took time away from his studies.

The impressive range of Ge Hong’s early education and his youthful literary endeavors also cast doubt on claims of extreme poverty. According to his biography in the Jin shu (History of the Jin Dynasty), it was during this early period that Ge began his study of the canon of texts, generally associated with ru jia, often translated simply as "Confucianism". Ge states that he began to read classics such as the "Shi jing" (Book of Odes) at fifteen, without the benefit of a tutor, and could recite from memory those books he studied and grasp their essential meaning. His extensive reading approached "ten thousand chapters", a number meant to suggest the dizzying scope of his education. The "ten thousand things" is used often in Daoist texts to describe the vast manifestations, life forms or types of matter in the reality of the Dao.

In reality, his formal education probably began much earlier, as elsewhere in his autobiographical postface, Ge states that he had already begun to write poetry, rhapsodies, and other miscellaneous writings by the age of fourteen or fifteen (c. 298), all of which he later destroyed. Ge’s statements regarding early poverty and belated studies convey the sense that his education was largely the product of his own acumen and determination rather than his privileged social status. Such exaggerations may be regarded as literary conventions, intended to show the unique nature of his education in the face of financial difficulties brought on by his father’s death. Claims that he started his education as late as fifteen may also be an oblique literary reference to Confucius’ own statement in Lunyu (Analects) 2.4 that, "At fifteen, I set my heart on learning."

Around this time, or perhaps a little before (c. 297) Ge, then fourteen years old, entered into the tutelage of Zheng Yin, an accomplished classical scholar who had turned to esoteric studies later in life. According to Ge’s lengthy and colorful description of his teacher, Zheng was over eighty years old but still remarkably hale. He was a master of the so-called "Five Classics" who continued to teach the Li ji (Book of Rites) and the Shu (Documents), was a teacher of the esoteric arts of longevity, divination and astrology, and was even an accomplished musician! Zheng Yin’s instruction in the esoteric arts emphasized the manufacture of the "gold elixir" or jin dan, which he considered the only truly significant means to achieve transcendence. His influence is reflected in portions of Hong’s writings that endorse alchemy, but are critical of dietary regimens, herbs and other popular methods of longevity.

The process of learning alchemical recipes and receiving scriptures combined rituals, oral instruction and textual transmission. Ge states that his master carefully limited access to these texts among his more than fifty disciples. He was only permitted to copy out a few, but lists the titles of many more in his own writings. Indeed, Ge’s "Inner Chapters" is remarkable for its extensive bibliography of alchemical scriptures, most of which exist only in fragments today. Only to Ge did Zheng Yin transmit texts such as the Sanhuang neiwen (Esoteric Writings of the Three Sovereigns), which Zheng considered to be among the most important alchemical scriptures. Ge also received three scriptures from the Grand Purity (Taiqing 太清) tradition that originated in northern China, along with their accompanying esoteric, oral instructions. These texts were relatively unknown south of the Yangtze River, and their transmission to Ge may be regarded as a rare event that owed something to Zheng Yin’s close relationship to Ge’s family. Zheng Yin was the pupil of Ge’s granduncle Ge Xuan, who was in turn the pupil of the well known Han fangshi (occultist), Zuo Ci. Ge claims that these three texts were revealed through divine revelation to Zuo Ci, who later fled south to escape the chaos that followed the collapse of the Han dynasty.

References to canonical texts throughout Baopuzi raise the

possibility that Ge received a well rounded, if untraditional education,

from Zheng Yin, who was a teacher of both the orthodox Han literary

canon, as well as a master of esoteric studies. Ge’s description of his

tenure as one of Zheng Yin’s students recalls a private school, complete

with students doing work, such as sweeping the floors and chopping

firewood, in addition to their studies. Traditional education in the

so-called Confucian canon was out of fashion in Ge’s era. It may be the

case that Ge, deprived of his father’s instruction and furthermore

suffering the loss of his father’s library, attended a private school

that emphasized the non-canonical education, popular after the

dissolution of the Han. Zheng Yin’s close relationship to Ge’s family,

through Ge Xuan, might have naturally led to Ge Hong’s privileged

instruction in important esoteric texts.

Around 302, Zheng Yin, perhaps catching wind of the growing political turmoil, moved to Mount Huo in modern Fujian province to live in seclusion with a few select disciples. Ge did not accompany him, and reported that Zheng Yin’s exact whereabouts were unknown. In the following year, at the age of twenty, Ge began his official career with the military service, swept up in a tide of rebellion and warfare. He was appointed to the position of Defender Commandant, and ordered to raise a militia of several hundred to fight Shi Bing, an ally of the rebel, Zhang Chang, who sought to overthrow the Western Jin. Hong, who served under the command of Gu Mi, is not mentioned in official accounts of this conflict. In his autobiographical postface, for a literati he is unusually forthcoming about his battlefield heroics and abilities as a commander. Although he only admitted to killing two men and a horse by arrow, such accounts of Ge’s bravery is made all the more startling by his insistence that in his youth, he was so weak that he could not even draw a bow. Such self deprecating physical descriptions are probably best seen in the same light as his claims of early poverty. Based on his service record, it is more likely that Ge received military training in his youth, and was skilled in both the use of arms and strategy.

After Shi Bing’s force was destroyed, he was discharged and recognized for his service with the honorary title of "General Who Makes the Waves Submit". According to Ge’s account, soon after he left for the Jin capital of Luoyang to search for "unusual books". In reality, Ge’s journey may have been inspired by the more mundane desire to parlay his military honors into an official position at the capital. During this time, the so-called "War of the Eight Princes" consumed the area around Luoyang, a civil conflict that would eventually result in almost sixteen years of political chaos, prior to the collapse of the Western Jin in 317. To the southeast of Luoyang, the rebel, Chen Min, occupied a large swath of territory east of the Yangzi River, and declared himself the Duke of Chu. Owing to such a staggering degree of social upheaval, Ge found the way north impassable, and wandered in the south.

Around 306, Ge entered into the service of Ji Han (c. 262 - 306), a

relative of the poet and essayist, Ji Kang. At the time, Ji Han was

fighting several rebel groups in the south, and had just been appointed

Regional Inspector of Guangzhou.

Ge states that he saw employment with Ji Han as a means to move south,

and escape political and social chaos. It may also be that Ge and Ji Han

shared a bond of friendship, based on mutual interests and literary

aspirations. Like Ge, Ji Han was a military official who also excelled

in literature and dabbled in esoteric studies. Ji Han wrote the

"Rhapsody on Cold Victual Powder", which lauds the effectiveness of a

drug, popular with the literati during the Six Dynasties

era, as well as a tract, entitled "Description of Herbs and Plants of

the Southern Region" that is no longer extant. The period of Hong’s

employment with Ji Han was extremely brief, for Ji Han was killed while

en route to assuming his new position in Guangzhou. Ge, who had traveled

ahead of his new employer, was left in the south with neither job nor

political patron. Thus Ge’s early official career came to an abrupt and

unexpected end.

Rather than return north, Ge refused other honors and remained in the south, living as a recluse on Mount Luofu for the next eight years before returning to his native Jurong around 314. The decision meant that Ge avoided much of the political upheaval that ravaged the Jin state, as various contenders for the throne pillaged Luoyang over the next several years. It was probably during this time on Mt. Luofu that Ge began his relationship with Bao Jing (260 - 327). According to the biographies of both Bao Jing and Ge, Bao was an adept in a wide variety of esoteric studies, including medicine, and transmitted his techniques and knowledge to Hong. Conversely, Bao Jing "valued Ge very much, and married a daughter to him". Evidence for the precise timing of their initial meeting is largely circumstantial. Around 312, Bao was appointed Governor of Nanhai prefecture, not far from Mt. Luofu. Some sources suggest that Bao Jing often traveled to Mt. Luofu to study esoteric arts, during which time he would have certainly met Ge. While such accounts may be apocryphal, timing and proximity raise the possibility that the two men began their relationship while Ge lived in the far south.

This period of reclusion appears to have been a time of great literary productivity for Ge. In addition to a remarkable body of writing that is now sadly lost, he also composed those extant works for which he is known today, the Baopuzi, and the Shenxian zhuan. It is nearly impossible to narrow down precisely the dates of composition for Ge’s surviving work. Autobiographical statements within the Baopuzi seem to indicate quite clearly that by the end of his residence on Mt. Luofu, or soon thereafter, Ge had written the Baopuzi as it exists today, arranged into "Inner" and "Outer" sections of twenty and fifty chapters, respectively, and had moreover composed a work called Shenxian zhuan.

Several modern scholars (notably Chen Feilong) have speculated based

on close textual study that Ge revised or rewrote these twenty chapters

after his final retirement in 331, and that the "Inner Chapters"

mentioned here might be an altogether different edition of the work that

exists today by that title. This notion, whether or not it is correct,

points more generally to the difficulties of working in a textual

tradition, rich in editorial revision and forgery. Robert Campany’s

(2002) painstaking attempt to reconstruct the Shenxian zhuan illustrates many of the problems confronting modern scholars of Ge and early Chinese texts. According to Campany, the Shenxian zhuan

as it now exists, is riddled with amendments, errors, and later

additions. None of the current editions, collected within various encyclopedia of early texts, can be said to be the Shenxian zhuan, written by Ge. Campany’s study suggests that many problems of

authorship and editorial corruption in Ge’s surviving work remain to be

solved.

Ge states that the Baopuzi, taken as a whole, constitutes his attempt to establish a single school (yi jia) of thought. The division of the Baopuzi into "Inner" and "Outer Chapters" speaks to Ge’s interest in both esoteric studies and social philosophy. According to Ge’s own account, he wrote the "Inner Chapters" to argue for the reality and attainability of divine transcendence, while the "Outer Chapters" blends Confucian and Legalist rhetoric to propose solutions for the social and political problems of his era. For a long time, the two parts of the text circulated independently, and were almost always categorized under different headings in officially sanctioned bibliographies.

The two volumes of the Baopuzi differ in style, as well as in content. Both adopt the convention of a fictional, hostile interlocutor who poses questions to the author and challenges his claims, although the "Inner Chapters" employs this style to a more significant degree. Ge’s thesis in the "Inner Chapters" is extremely focused, pursuing a single argument with great discipline and rigor. In contrast, the "Outer Chapters" is more diffused, addressing a variety of issues ranging from eremitism and literature to the proper employment of punishments, and a pointed criticism of the process of political promotions. The style of the "Outer Chapters" is very dense, reflecting the richness of the Chinese literary tradition through frequent literary and historical allusions, and diction, that at times recalls the most obscure rhyme prose of the Han era.

As a single work of philosophy, the two sections taken together reflect Ge’s desire to understand dao and ru, or Daoism and Confucianism, in terms of one another. In Ge’s terms, dao is the "root" and ru is the "branch". However, although he considered following the dao superior to the rules of social conduct associated with the Confucian tradition, Ge viewed each as appropriate within its proper sphere. According to his paradigm that is drawn from pre-Qin and Han sources, when the sage kings followed the dao, society was well ordered, and the natural world proceeded without calamities. As the dao declined, the ethical prescriptions of the ru arose to remedy the resulting social ills and natural disasters. Thus in Ge’s view, Daoism and Confucianism both possess an ethical and political dimension by bringing order to the human and natural world. However, because most people have difficulty following or understanding the dao, Confucianism (along with a healthy dose of Legalism) is necessary to enact social order.

On an individual level, Ge considered moral and ethical cultivation

of the so-called Confucian virtues to be the basis of divine transcendence. His philosophy does not advocate a rejection of the

material world on either an individual or a social level. Seekers of

longevity must first rectify and bring order to their own person before

achieving loftier ambitions. Ge appears to have made some effort to

embody this ideal, simultaneously holding political office, while

pursuing elixirs of transcendence.

In the Baopuzi, Ge places a high value on literature and regards writing as an act of social and political significance, equivalent to virtuous action, and at one point stating, "The relationship between writings and virtuous actions is [like that of two different names for one thing]". This sentiment reflects a trend, begun during the later Han, which saw literature as an increasingly significant tool with which an individual could establish an enduring legacy. In times of political uncertainty, when ambitious literati faced real dangers and obstacles to social or political advancement, this view of literature took on added significance.

The idea that writing was a fundamentally moral act may have

contributed to Ge’s high opinion of the literature of his era. Unlike

the classical scholars of the later Han period, who revered the writers

of antiquity with an almost fanatical reverence, Ge regarded the works

of his contemporaries (and by extension his own) as equal to, if not

greater than, the writers of the past: "Simply because a book does not

come from the sages [of the past], we should not disregard words within

it that help us to teach the dao." Ge concedes that the proliferation of

writing in his own time had led to many works of poor quality; in

particular, he criticizes contrived and overly ornamental prose that

obscures the intentions of the author. However, he rejects the idea that

established tradition alone speaks to the quality, utility, or virtue

of any literary work.

Shortly after emerging from reclusion and returning to his family home of Jurong around 314, Ge received an appointment as Clerk to the Prince of Langya, Sima Rui (276 - 322), who served as Prime Minister from 313 until 316. The exact date of the appointment is unclear, but it certainly occurred after Ge’s return to Jurong, and was probably early in Sima Rui’s tenure as Prime Minister. Sima Rui used the position of Clerk, which was for the most part an honorary appointment, to woo talented officials, and bring them into the fold of his administration. He appointed over one hundred people (some sources say 106) in this way, and the appointments were probably an indication of his growing political power. In 317, the Western Jin collapsed after years of civil conflict, and an invasion from non - Chinese people to the north. Sima Rui stepped into this power vacuum, moving the Jin court south to Jiankang (present day Nanjing), and taking the title of "King of Jin" as a preliminary step towards claiming the mantle of emperor.

The refugee court in Jiankang was eager to solidify its position among the southern gentry families upon whom it now depended for its survival and granted numerous official appointments and honorary titles. Ge was recognized for his previous military service with the honorary title of "Marquis of the Region Within the Pass", and awarded an income of two hundred households in Jurong. Finally, in 318, Sima Rui proclaimed himself Emperor Yuan (reigned 318 - 323), becoming the first ruler of the Eastern Jin (317 - 420).

Among the prerogatives of a new dynasty was writing the history of its predecessor. Around 318, the influential minister, Wang Dao (276 - 339), commissioned Gan Bao (the author of Soushen ji (In Search of the Supernatural)), Wang Yin, and Guo Pu (276 - 324) to write the Jin ji (Record of the Jin). Wang Dao, and others in his coterie, would exert considerable influence over Ge’s later official career. In 324, Wang Dao was made Regional Inspector of Yangzhou. Shortly thereafter, beginning in 326, Ge was summoned to fill a variety of appointments in Wang Dao’s administration, such as Recorder of Yangzhou, Secretary to the Minister of Education, and the military post of Administrative Advisor.

The fact that Ge’s official biography, and his autobiographical writing, do not mention any actual duties performed in these positions suggests that the appointments may have been honorary to some degree. It is also possible that he omitted mention of these positions in his own writings in order to preserve the veil of eremitism that obscures his autobiographical account. Wang Dao seems to have been a collector of famous recluses, perhaps out of a desire to project an image of virtuous authority. According to the official biography of Ge’s contemporary, Guo Wen (Jinshu 64), Wang built a garden in which Guo resided as a kind of hermit - in - residence, entertaining Wang Dao’s entourage with philosophical debate and clever conversation. Thus, in addition to his past services on behalf of the Jin court, Ge’s self consciously crafted image of eremitism may have contributed to his success within Wang Dao’s administration. Regardless, it seems clear that Wang Dao knew of Ge by reputation, and sought to bring him into the fold of his personal staff.

During his tenure within Wang Dao’s administration, Ge also came to the attention of the historian, Gan Bao. Gan seems to have recognized Ge’s literary acumen, and offered him several positions on his staff. He recommended Ge for the office of Senior Recorder, a position within the Bureau of Scribes (shi guan) that was in responsible for compiling the "Imperial Diary", as well as the office of Editorial Director, which would have involved Ge in writing of state sanctioned historiography. These recommendations may have come about as a result of Gan Bao’s charge to introduce talented men to high office, as well as mutual admiration between two decidedly eclectic scholars.

According to his official biography, Ge refused these positions on

Gan Bao’s staff. However, as with many details of Ge’s official life, it

is difficult to separate fact from literary persona. The bibliographic

treatise of the Sui shu (History of the Sui Dynasty) contains an entry for a work entitled, Hanshu chao (Notes on the History of the Former Han), a text that is now lost, by Senior Recorder Hong. Moreover, authorship of the Xijing zazhi

(Miscellanies of the Western Capital) — a collection of historical

anecdotes that probably dates from the Han period — was long ascribed to

Ge. It appears that Ge possessed some reputation for historical writing

during his own lifetime, and so the possibility that he accepted an

appointment on Gan Bao’s staff is not entirely out of the question.

Several events during this final period of Ge’s public life may have contributed to his eventual decision to relocate once again to the far south. Around 328, Su Jun’s (died 328) rebellion ravaged part of what is now modern Zhejiang province, exposing the fragility of political life under the Eastern Jin regime. Ge also suffered the death of his much admired contemporary, Guo Wen, in the same year, an event that may have impressed upon him the fleeting nature of life in uncertain times, which is a recurring theme in his surviving writing. According to several passages in the Baopuzi, his ultimate goal lay in following the tradition of cultural icons and seekers of immortality, such as Chi Songzi (Master Red Pine) by living in reclusion, and concocting elixirs of transcendence.

Although retirement for the purpose of pursuing transcendence was both a popular literary trope, and a widely used avenue of political retreat, works such as the Baopuzi "Inner Chapters", and Shenxian zhuan, demonstrate that Ge was relatively sincere in this desire, which seems to have been based on strong sectarian convictions. According to his official biography, in 331, at the age of forty - nine he requested an appointment on the periphery of the Jin state as District Magistrate of Julou, located in modern day Vietnam, an area that was reputed to possess the raw materials required for elixirs of transcendence. The emperor refused his initial request, but assented when Ge repeated the petition. His biography in the Jinshu states that Ge departed for the south with his sons and nephews.

Ge’s party never reached their destination. In Guangzhou, a career military official named Deng Yue — who had become Regional Inspector of Guangzhou the year before in 330 — detained him indefinitely. The reason for Deng’s interest in Ge is unclear. Deng Yue may have been reluctant to allow an honored member of the gentry to pass beyond the limits of Jin state, or he may have seen the presence of a scholarly gentleman with Ge’s reputation as an addition to his own prestige. Deng Yue, a seasoned campaigner who entertained an ambitious agenda, may also have been attracted to Ge’s experience in military matters, and desired his services. In 336 and again in 339, Deng waged several successful campaigns in modern Yunnan and Sichuan provinces, and may have seen Hong as an asset to his staff. Sources are inconclusive, stating only that Hong was not allowed to continue south, and instead settled once again on Mt. Luofu.

Ge’s residence on Mt. Luofu marks the end of his public career. All sources indicate that he devoted his remaining years to scholarship, writing, and pursuing elixirs of transcendence. Deng Yue issued a memorial requesting that Hong fill the post of Governor of Dong Guan near Nanhai, but Hong adamantly refused the appointment. Deng instead gave the post of Secretarial Aid to the son of Ge's eldest brother, Ge Wang, but Ge never again filled an official position.

The nature of Ge’s literary activity during this period of time is unknown. Whether he devoted himself strictly to esoteric (nei xue) studies, edited the Baopuzi or any other of his earlier works, or even continued to write poetry, is entirely a matter of speculation. Although relatively speaking much of Ge’s work survives, with regards to his total effort, only a small fraction still exists. It is reasonable to assume that Ge continued to be a prolific author, even in retirement. The Tianwen zhi (Treatise on Astronomy) in the Jinshu reports that around the year 342, a certain Yu Xi from Kuaiji authored a work called Antian lun (Discussion on Complying with Heaven), which Ge supposedly criticized. No other information is available regarding Hong’s argument with the contents of this work, but the anecdote suggests that he was not living in an intellectual vacuum, despite his retirement from official life.

In 343, Hong died on Mt. Luofu. The account of his passing as found in his official biography is more hagiography than history. Supposedly, Ge sent a letter to Deng Yue, hinting at his approaching end. Deng rushed to Ge’s home, but found him already dead. Strangely, Ge’s body was light and supple, as if alive, and his contemporaries all supposed that he had finally achieved transcendence with the technique of shi jie, sometimes translated as "corpse liberation". His biography moreover follows a tradition that Ge was eighty - one when he died, an important number in Daoist numerology, but there is little doubt among modern scholars that this tradition is false, and Ge died at the age of sixty.

The fact that the end of his biography adopts the tone of religious hagiography suggests that Ge was primarily seen in terms of his esoteric studies as early as the Tang period. But Ge also possessed a legacy as a capable official who had the courage to serve in office during uncertain times. During the Yuan dynasty (1271 - 1368), the scholar Zhao Daoyi lauded Ge for "disregarding favor, but not forgetting his body". Zhao admired Hong for continuing to occupy official positions during a period when scholars "hid away and did not return".

More recently, the richness of Ge’s work has inspired many different avenues of academic research and popular interest. Not surprisingly, most studies of Hong, both in Chinese and in English, focus on his esoteric writings, such as the "Inner Chapters" and Shenxian zhuan. His position in the history of Daoism, as a whole, has been subject to considerable scrutiny and academic study. Recent surveys of the history of Daoism in Chinese have also emphasized Ge’s importance in the history of science, based on his detailed descriptions of alchemical processes, which are frequently studied in terms of modern chemistry. This view is largely based on the work of Joseph Needham, T.L. Davis, and other Western scholars. Although the significance of Hong’s alchemical and religious writing seems clear, little energy has been invested in his "Outer Chapters", despite its considerable length and complexity. Beyond Jay Sailey’s incomplete translation and appended study, most serious work on the "Outer Chapters" is scattered throughout general studies of literary criticism, political theory, or social history.

A temple dedicated to Ge stands in the hills north of West Lake

(Xihu) in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province. According to the monks and nuns

who live at the temple, it was on this site that Ge wrote Baopuzi,

and eventually attained transcendence. Ge supposedly answers prayers

from a Daoist worshiper with a healthy mind and body. Further south,

near Ningbo,

lies an eco-tourist destination that also claims to be the site of Ge’s

alleged transcendence. Visitors are rewarded with an exceptional hike

through a narrow gorge of remarkable natural beauty. These contradictory

claims, together with conflicting historical sources, reflect the

complexity of Ge’s legacy as a figure of continued religious,

historical and literary importance.

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (April 15, 1452 – May 2, 1519, Old Style) was an Italian Renaissance polymath: painter, sculptor, architect, musician, scientist, mathematician, engineer, inventor, anatomist, geologist, cartographer, botanist, and writer whose genius, perhaps more than that of any other figure, epitomized the Renaissance humanist ideal. Leonardo has often been described as the archetype of the Renaissance Man, a man of "unquenchable curiosity" and "feverishly inventive imagination". He is widely considered to be one of the greatest painters of all time and perhaps the most diversely talented person ever to have lived. According to art historian Helen Gardner, the scope and depth of his interests were without precedent and "his mind and personality seem to us superhuman, the man himself mysterious and remote". Marco Rosci points out, however, that while there is much speculation about Leonardo, his vision of the world is essentially logical rather than mysterious, and that the empirical methods he employed were unusual for his time.

Born out of wedlock to a notary, Piero da Vinci, and a peasant woman, Caterina, at Vinci in the region of Florence, Leonardo was educated in the studio of the renowned Florentine painter, Verrocchio. Much of his earlier working life was spent in the service of Ludovico il Moro in Milan. He later worked in Rome, Bologna and Venice, and he spent his last years in France at the home awarded him by Francis I.

Leonardo was and is renowned primarily as a painter. Among his works, the Mona Lisa is the most famous and most parodied portrait and The Last Supper the most reproduced religious painting of all time, with their fame approached only by Michelangelo's The Creation of Adam. Leonardo's drawing of the Vitruvian Man is also regarded as a cultural icon, being reproduced on items as varied as the euro, textbooks and T-shirts. Perhaps fifteen of his paintings survive, the small number because of his constant, and frequently disastrous, experimentation with new techniques, and his chronic procrastination. Nevertheless, these few works, together with his notebooks, which contain drawings, scientific diagrams, and his thoughts on the nature of painting, compose a contribution to later generations of artists only rivaled by that of his contemporary, Michelangelo.

Leonardo is revered for his technological ingenuity. He

conceptualized a helicopter, a tank, concentrated solar power, a

calculator,

the double hull, and he outlined a rudimentary theory of plate

tectonics. Relatively few of his designs were constructed or were even

feasible during his lifetime, but some of his smaller inventions, such as an automated bobbin winder and a machine for testing the tensile strength of wire, entered the world of manufacturing unheralded.

He made important discoveries in anatomy, civil engineering, optics and

hydrodynamics, but he did not publish his findings and they had no

direct influence on later science.

Leonardo was born on April 15, 1452 (Old Style), "at the third hour of the night" in the Tuscan hill town of Vinci, in the lower valley of the Arno River in the territory of the Medici ruled Republic of Florence. He was the out - of - wedlock son of the wealthy Messer Piero Fruosino di Antonio da Vinci, a Florentine legal notary, and Caterina, a peasant. Leonardo had no surname in the modern sense, “da Vinci” simply meaning “of Vinci”: his full birth name was "Lionardo di ser Piero da Vinci", meaning "Leonardo, (son) of (Mes)ser Piero from Vinci". The inclusion of the title "ser" indicated that Leonardo's father was a gentleman.

Little is known about Leonardo's early life. He spent his first five years in the hamlet of Anchiano in the home of his mother, then from 1457 he lived in the household of his father, grandparents and uncle, Francesco, in the small town of Vinci. His father had married a sixteen year old girl named Albiera, who loved Leonardo but died young. When Leonardo was sixteen his father married again, to twenty year old Francesca Lanfredini. It was not until his third and fourth marriages that Ser Piero produced legitimate heirs.

Leonardo received an informal education in Latin, geometry and mathematics. In later life, Leonardo only recorded two childhood incidents. One, which he regarded as an omen, was when a kite dropped from the sky and hovered over his cradle, its tail feathers brushing his face. The second occurred while exploring in the mountains. He discovered a cave and was both terrified that some great monster might lurk there and driven by curiosity to find out what was inside.

Leonardo's early life has been the subject of historical conjecture. Vasari,

the 16th century biographer of Renaissance painters tells of how a

local peasant made himself a round shield and requested that Ser Piero

have it painted for him. Leonardo responded with a painting of a monster

spitting fire which was so terrifying that Ser Piero sold it to a

Florentine art dealer, who sold it to the Duke of Milan.

Meanwhile, having made a profit, Ser Piero bought a shield decorated

with a heart pierced by an arrow, which he gave to the peasant.

In 1466, at the age of fourteen, Leonardo was apprenticed to the artist Andrea di Cione, known as Verrocchio, whose workshop was "one of the finest in Florence". Other famous painters apprenticed or associated with the workshop include Domenico Ghirlandaio, Perugino, Botticelli, and Lorenzo di Credi. Leonardo would have been exposed to both theoretical training and a vast range of technical skills, including drafting, chemistry, metallurgy, metal working, plaster casting, leather working, mechanics and carpentry as well as the artistic skills of drawing, painting, sculpting and modelling.

Much of the painted production of Verrocchio's workshop was done by his employees. According to Vasari, Leonardo collaborated with Verrocchio on his The Baptism of Christ, painting the young angel holding Jesus' robe in a manner that was so far superior to his master's that Verrocchio put down his brush and never painted again. On close examination, the painting reveals much that has been painted or touched up over the tempera using the new technique of oil paint, with the landscape, the rocks that can be seen through the brown mountain stream and much of the figure of Jesus bearing witness to the hand of Leonardo. Leonardo may have been the model for two works by Verrocchio: the bronze statue of David in the Bargello and the Archangel Raphael in Tobias and the Angel.

By 1472, at the age of twenty, Leonardo qualified as a master in the Guild of St Luke, the guild of artists and doctors of medicine, but even after his father set him up in his own workshop, his attachment to Verrocchio was such that he continued to collaborate with him. Leonardo's earliest known dated work is a drawing in pen and ink of the Arno valley, drawn on August 5, 1473.Florentine court records of 1476 show that Leonardo and three other young men were charged with sodomy and acquitted. From that date until 1478 there is no record of his work or even of his whereabouts. In 1478 he left Verrocchio's studio and was no longer resident at his father's house. One writer, the "Anonimo" Gaddiano claims that in 1480 he was living with the Medici and working in the Garden of the Piazza San Marco in Florence, a Neo - Platonic academy of artists, poets and philosophers that the Medici had established. In January 1478, he received his first of two independent commissions: to paint an altarpiece for the Chapel of St. Bernard in the Palazzo Vecchio and, in March 1481, The Adoration of the Magi for the Monks of San Donato a Scopeto. Neither commission was completed, the second being interrupted when Leonardo went to Milan.

In 1482 Leonardo, who according to Vasari was a most talented musician, created a silver lyre in the shape of a horse's head. Lorenzo de' Medici sent Leonardo to Milan, bearing the lyre as a gift, to secure peace with Ludovico il Moro, Duke of Milan. At this time Leonardo wrote an often quoted letter describing the many marvelous and diverse things that he could achieve in the field of engineering and informing Ludovico that he could also paint.

Leonardo worked in Milan from 1482 until 1499. He was commissioned to paint the Virgin of the Rocks for the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception and The Last Supper for the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie. Between 1493 and 1495 Leonardo listed a woman called Caterina among his dependents in his taxation documents. When she died in 1495, the list of funeral expenditures suggests that she was his mother.

Leonardo was employed on many different projects for Ludovico,

including the preparation of floats and pageants for special occasions,

designs for a dome for Milan Cathedral and a model for a huge equestrian

monument to Francesco Sforza,

Ludovico's predecessor. Seventy tons of bronze

were set aside for casting it. The monument remained unfinished for

several years, which was not unusual for Leonardo. In 1492 the clay

model of the horse was completed. It surpassed in size the only two

large equestrian statues of the Renaissance, Donatello's statue of

Gattemelata in Padua and Verrocchio's Bartolomeo Colleoni in Venice, and

became known as the "Gran Cavallo".

Leonardo began making detailed plans for its casting, however, Michelangelo insulted Leonardo by implying that he was unable to cast it. In November 1494 Ludovico gave the bronze to be used for cannon to defend the city from invasion by Charles VIII.

At the start of the Second Italian War in 1499, the invading French troops used the life size clay model for the "Gran Cavallo" for target practice. With Ludovico Sforza overthrown, Leonardo, with his assistant Salai and friend, the mathematician Luca Pacioli, fled Milan for Venice, where he was employed as a military architect and engineer, devising methods to defend the city from naval attack. On his return to Florence in 1500, he and his household were guests of the Servite monks at the monastery of Santissima Annunziata and were provided with a workshop where, according to Vasari, Leonardo created the cartoon of The Virgin and Child with St. Anne and St. John the Baptist, a work that won such admiration that "men and women, young and old" flocked to see it "as if they were attending a great festival".

In Cesena, in 1502 Leonardo entered the service of Cesare Borgia, the

son of Pope Alexander VI, acting as a military architect and engineer

and traveling throughout Italy with his patron. Leonardo created a map of Cesare Borgia's stronghold, a town plan of Imola

in order to win his patronage. Maps were extremely rare at the time and

it would have seemed like a new concept; upon seeing it, Cesare hired

Leonardo as his chief military engineer and architect. Later in the year, Leonardo produced another map for his patron, one of Chiana Valley,

Tuscany, so as to give his patron a better overlay of the land and

greater strategic position. He created this map in conjunction with his

other project of constructing a dam from the sea to Florence in order to

allow a supply of water to sustain the canal during all seasons.

Leonardo returned to Florence where he rejoined the Guild of St Luke on October 18, 1503, and spent two years designing and painting a mural of The Battle of Anghiari for the Signoria, with Michelangelo designing its companion piece, The Battle of Cascina. In Florence in 1504, he was part of a committee formed to relocate, against the artist's will, Michelangelo's statue of David.

In 1506 Leonardo returned to Milan. Many of his most prominent pupils or followers in painting either knew or worked with him in Milan, including Bernardino Luini, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio and Marco D'Oggione. However, he did not stay in Milan for long because his father had died in 1504, and in 1507 he was back in Florence trying to sort out problems with his brothers over his father's estate. By 1508 Leonardo was back in Milan, living in his own house in Porta Orientale in the parish of Santa Babila.

From September 1513 to 1516, Leonardo spent much of his time living in the Belvedere in the Vatican in Rome, where Raphael and Michelangelo were both active at the time.

In October 1515, Francis I of France recaptured Milan. On December 19,

Leonardo was present at the meeting of Francis I and Pope Leo X, which

took place in Bologna. Leonardo was commissioned to make for Francis a

mechanical lion which

could walk forward, then open its chest to reveal a cluster of lilies. In 1516, he entered François' service, being given the use of the manor house Clos Lucé

near the king's residence at the royal Château d'Amboise. It was here

that he spent the last three years of his life, accompanied by his

friend and apprentice, Count Francesco Melzi, and supported by a pension

totalling 10,000 scudi.

Leonardo died at Clos Lucé, on May 2, 1519. Francis I had become a close friend. Vasari records that the king held Leonardo's head in his arms as he died, although this story, beloved by the French and portrayed in romantic paintings by Ingres, Ménageot and other French artists, as well as by Angelica Kauffmann, may be legend rather than fact. Vasari states that in his last days, Leonardo sent for a priest to make his confession and to receive the Holy Sacrament. In accordance to his will, sixty beggars followed his casket. He was buried in the Chapel of Saint - Hubert in Château d'Amboise. Melzi was the principal heir and executor, receiving as well as money, Leonardo's paintings, tools, library and personal effects. Leonardo also remembered his other long time pupil and companion, Salai and his servant Battista di Vilussis, who each received half of Leonardo's vineyards, his brothers who received land, and his serving woman who received a black cloak "of good stuff" with a fur edge.

Some 20 years after Leonardo's death, Francis was reported by the goldsmith and sculptor Benevenuto Cellini

as saying: "There had never been another man born in the world who knew

as much as Leonardo, not so much about painting, sculpture and architecture, as that he was a very great philosopher."

Florence, at the time of Leonardo's youth, was the center of Christian Humanist thought and culture. Leonardo commenced his apprenticeship with Verrocchio in 1466, the year that Verrocchio's master, the great sculptor Donatello, died. The painter Uccello, whose early experiments with perspective were to influence the development of landscape painting, was a very old man. The painters Piero della Francesca and Fra Filippo Lippi, sculptor Luca della Robbia, and architect and writer Leon Battista Alberti were in their sixties. The successful artists of the next generation were Leonardo's teacher Verrocchio, Antonio Pollaiuolo and the portrait sculptor, Mino da Fiesole whose lifelike busts give the most reliable likenesses of Lorenzo Medici's father Piero and uncle Giovanni.

Leonardo's youth was spent in a Florence that was ornamented by the works of these artists and by Donatello's contemporaries, Masaccio, whose figurative frescoes were imbued with realism and emotion and Ghiberti whose Gates of Paradise, gleaming with gold leaf, displayed the art of combining complex figure compositions with detailed architectural backgrounds. Piero della Francesca had made a detailed study of perspective, and was the first painter to make a scientific study of light. These studies and Alberti's Treatise were to have a profound effect on younger artists and in particular on Leonardo's own observations and artworks.

Massaccio's "The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden"

depicting the naked and distraught Adam and Eve created a powerfully

expressive image of the human form, cast into three dimensions by the

use of light and shade

which was to be developed in the works of Leonardo in a way that was to

be influential in the course of painting. The humanist influence of

Donatello's "David" can be seen in Leonardo's late paintings,

particularly John the Baptist.

A prevalent tradition in Florence was the small altarpiece of the Virgin and Child. Many of these were created in tempera or glazed terracotta by the workshops of Filippo Lippi, Verrocchio and the prolific della Robbia family. Leonardo's early Madonnas such as The Madonna with a carnation and The Benois Madonna followed this tradition while showing idiosyncratic departures, particularly in the case of the Benois Madonna in which the Virgin is set at an oblique angle to the picture space with the Christ Child at the opposite angle. This compositional theme was to emerge in Leonardo's later paintings such as The Virgin and Child with St. Anne.

Leonardo was a contemporary of Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio and Perugino, who were all slightly older than he was. He would have met them at the workshop of Verrocchio, with whom they had associations, and at the Academy of the Medici.

Botticelli was a particular favorite of the Medici family, and thus

his success as a painter was assured. Ghirlandaio and Perugino were both

prolific and ran large workshops. They competently delivered

commissions to well satisfied patrons who appreciated Ghirlandaio's

ability to portray the wealthy citizens of Florence within large

religious frescoes, and Perugino's ability to deliver a multitude of

saints and angels of unfailing sweetness and innocence.

These three were among those commissioned to paint the walls of the Sistine Chapel, the work commencing with Perugino's employment in 1479. Leonardo was not part of this prestigious commission. His first significant commission, The Adoration of the Magi for the Monks of Scopeto, was never completed.

In 1476, during the time of Leonardo's association with Verrocchio's workshop, the Portinari Altarpiece by Hugo van der Goes arrived in Florence, bringing new painterly techniques from Northern Europe which were to profoundly affect Leonardo, Ghirlandaio, Perugino and others. In 1479, the Sicilian painter Antonello da Messina, who worked exclusively in oils, traveled north on his way to Venice, where the leading painter Giovanni Bellini adopted the technique of oil painting, quickly making it the preferred method in Venice. Leonardo was also later to visit Venice.

Like the two contemporary architects Bramante and Antonio da Sangallo the Elder

Leonardo experimented with designs for centrally planned churches, a

number of which appear in his journals, as both plans and views,

although none was ever realized.

Leonardo's political contemporaries were Lorenzo Medici (il Magnifico), who was three years older, and his younger brother Giuliano who was slain in the Pazzi Conspiracy in 1478. Ludovico il Moro who ruled Milan between 1479 – 1499 and to whom Leonardo was sent as ambassador from the Medici court, was also of Leonardo's age.

With Alberti, Leonardo visited the home of the Medici and through them came to know the older Humanist philosophers of whom Marsiglio Ficino, proponent of Neo Platonism; Cristoforo Landino, writer of commentaries on Classical writings, and John Argyropoulos, teacher of Greek and translator of Aristotle were the foremost. Also associated with the Academy of the Medici was Leonardo's contemporary, the brilliant young poet and philosopher Pico della Mirandola. Leonardo later wrote in the margin of a journal "The Medici made me and the Medici destroyed me." While it was through the action of Lorenzo that Leonardo received his employment at the court of Milan, it is not known exactly what Leonardo meant by this cryptic comment.

Although usually named together as the three giants of the High Renaissance,

Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael were not of the same generation.

Leonardo was twenty - three when Michelangelo was born and thirty - one when

Raphael was born.

Raphael only lived until the age of 37 and died in 1520, the year after

Leonardo, but Michelangelo went on creating for another 45 years.

Within Leonardo's lifetime, his extraordinary powers of invention, his "outstanding physical beauty", "infinite grace", "great strength and generosity", "regal spirit and tremendous breadth of mind" as described by Vasari, as well as all other aspects of his life, attracted the curiosity of others. One such aspect is his respect for life evidenced by his vegetarianism and his habit, according to Vasari, of purchasing caged birds and releasing them.

Leonardo had many friends who are now renowned either in their fields or for their historical significance. They included the mathematician Luca Pacioli, with whom he collaborated on a book in the 1490s, as well as Franchinus Gaffurius and Isabella d'Este. Leonardo appears to have had no close relationships with women except for his friendship with the two Este sisters, Beatrice and Isabella. He drew a portrait of Isabella while on a journey which took him through Mantua, and which appears to have been used to create a painted portrait, now lost.

Beyond friendship, Leonardo kept his private life secret. His

sexuality has been the subject of satire, analysis, and speculation.

This trend began in the mid 16th century and was revived in the 19th and

20th centuries, most notably by Sigmund Freud.

Leonardo's most intimate relationships were perhaps with his pupils

Salai and Melzi. Melzi, writing to inform Leonardo's brothers of his

death, described Leonardo's feelings for his pupils as both loving and

passionate. It has been claimed since the 16th century that these

relationships were of a sexual or erotic nature. Court records of 1476,

when he was aged twenty - four, show that Leonardo and three other young

men were charged with sodomy

in an incident involving a well known male prostitute. The charges were

dismissed for lack of evidence, and there is speculation that since one

of the accused, Lionardo de Tornabuoni, was related to Lorenzo de'

Medici, the family exerted its influence to secure the dismissal.

Since that date much has been written about his presumed homosexuality

and its role in his art, particularly in the androgyny and eroticism

manifested in John the Baptist and Bacchus and more explicitly in a number of erotic drawings.

Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno, nicknamed Salai or Il Salaino ("The Little Unclean One" i.e., the devil), entered Leonardo's household in 1490. After only a year, Leonardo made a list of his misdemeanors, calling him "a thief, a liar, stubborn and a glutton", after he had made off with money and valuables on at least five occasions and spent a fortune on clothes. Nevertheless, Leonardo treated him with great indulgence, and he remained in Leonardo's household for the next thirty years. Salai executed a number of paintings under the name of Andrea Salai, but although Vasari claims that Leonardo "taught him a great deal about painting", his work is generally considered to be of less artistic merit than others among Leonardo's pupils, such as Marco d'Oggione and Boltraffio. In 1515, he painted a nude version of the Mona Lisa, known as Monna Vanna. Salai owned the Mona Lisa at the time of his death in 1525, and in his will it was assessed at 505 lire, an exceptionally high valuation for a small panel portrait.

In 1506, Leonardo took on another pupil, Count Francesco Melzi, the son of a Lombard

aristocrat, who is considered to have been his favorite student. He

traveled to France with Leonardo and remained with him until Leonardo's

death. Melzi inherited the artistic and scientific works, manuscripts and collections of Leonardo and administered the estate.

Despite the recent awareness and admiration of Leonardo as a scientist and inventor, for the better part of four hundred years his fame rested on his achievements as a painter and on a handful of works, either authenticated or attributed to him that have been regarded as among the masterpieces.

These paintings are famous for a variety of qualities which have been

much imitated by students and discussed at great length by connoisseurs

and critics. Among the qualities that make Leonardo's work unique are

the innovative techniques that he used in laying on the paint, his

detailed knowledge of anatomy, light, botany and geology, his interest

in physiognomy

and the way in which humans register emotion in expression and gesture,

his innovative use of the human form in figurative composition, and his

use of the subtle gradation of tone. All these qualities come together

in his most famous painted works, the Mona Lisa, the Last Supper and the Virgin of the Rocks.

Leonardo's early works begin with the Baptism of Christ painted in conjunction with Verrocchio. Two other paintings appear to date from his time at the workshop, both of which are Annunciations. One is small, 59 centimetres (23 in) long and 14 centimeters (5.5 in) high. It is a "predella" to go at the base of a larger composition, in this case a painting by Lorenzo di Credi from which it has become separated. The other is a much larger work, 217 centimeters (85 in) long. In both these Annunciations, Leonardo used a formal arrangement, such as in Fra Angelico's two well known pictures of the same subject, of the Virgin Mary sitting or kneeling to the right of the picture, approached from the left by an angel in profile with rich flowing garment, raised wings and bearing a lily. Although previously attributed to Ghirlandaio, the larger work is now generally attributed to Leonardo.

In the smaller picture Mary averts her eyes and folds her hands in a

gesture that symbolised submission to God's will. In the larger picture,

however, Mary is not submissive. The girl, interrupted in her reading

by this unexpected messenger, puts a finger in her bible to mark the

place and raises her hand in a formal gesture of greeting or surprise. This calm young woman appears to accept her role as the Mother of God

not with resignation but with confidence. In this painting the young

Leonardo presents the humanist face of the Virgin Mary, recognising

humanity's role in God's incarnation.

In the 1480s Leonardo received two very important commissions and commenced another work which was also of ground breaking importance in terms of composition. Two of the three were never finished, and the third took so long that it was subject to lengthy negotiations over completion and payment. One of these paintings is that of St. Jerome in the Wilderness. Bortolon associates this picture with a difficult period of Leonardo's life, as evidenced in his diary: "I thought I was learning to live; I was only learning to die."

Although the painting is barely begun, the composition can be seen and it is very unusual. Jerome, as a penitent, occupies the middle of the picture, set on a slight diagonal and viewed somewhat from above. His kneeling form takes on a trapezoid shape, with one arm stretched to the outer edge of the painting and his gaze looking in the opposite direction. J. Wasserman points out the link between this painting and Leonardo's anatomical studies. Across the foreground sprawls his symbol, a great lion whose body and tail make a double spiral across the base of the picture space. The other remarkable feature is the sketchy landscape of craggy rocks against which the figure is silhouetted.

The daring display of figure composition, the landscape elements and personal drama also appear in the great unfinished masterpiece, the Adoration of the Magi, a commission from the Monks of San Donato a Scopeto. It is a complex composition, of about 250 x 250 centimeters. Leonardo did numerous drawings and preparatory studies, including a detailed one in linear perspective of the ruined classical architecture which makes part of the backdrop to the scene. But in 1482 Leonardo went off to Milan at the behest of Lorenzo de' Medici in order to win favor with Ludovico il Moro, and the painting was abandoned.

The third important work of this period is the Virgin of the Rocks

which was commissioned in Milan for the Confraternity of the Immaculate

Conception. The painting, to be done with the assistance of the de

Predis brothers, was to fill a large complex altarpiece, already

constructed. Leonardo chose to paint an apocryphal moment of the infancy of Christ when the infant John the Baptist,

in protection of an angel, met the Holy Family on the road to Egypt. In

this scene, as painted by Leonardo, John recognizes and worships Jesus

as the Christ. The painting demonstrates an eerie beauty as the graceful

figures kneel in adoration around the infant Christ in a wild landscape

of tumbling rock and whirling water. While the painting is quite large, about 200 × 120 centimeters,

it is not nearly as complex as the painting ordered by the monks of St

Donato, having only four figures rather than about fifty and a rocky

landscape rather than architectural details. The painting was eventually

finished; in fact, two versions of the painting were finished, one

which remained at the chapel of the Confraternity and the other which

Leonardo carried away to France. But the Brothers did not get their

painting, or the de Predis their payment, until the next century.

Leonardo's most famous painting of the 1490s is The Last Supper, painted for the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria della Grazie in Milan. The painting represents the last meal shared by Jesus with his disciples before his capture and death. It shows specifically the moment when Jesus has just said "one of you will betray me". Leonardo tells the story of the consternation that this statement caused to the twelve followers of Jesus.

The novelist Matteo Bandello observed Leonardo at work and wrote that some days he would paint from dawn till dusk without stopping to eat and then not paint for three or four days at a time. This was beyond the comprehension of the prior of the convent, who hounded him until Leonardo asked Ludovico to intervene. Vasari describes how Leonardo, troubled over his ability to adequately depict the faces of Christ and the traitor Judas, told the Duke that he might be obliged to use the prior as his model.

When finished, the painting was acclaimed as a masterpiece of design

and characterization, but it deteriorated rapidly, so that within a

hundred years it was described by one viewer as "completely ruined".

Leonardo, instead of using the reliable technique of fresco, had used

tempera over a ground that was mainly gesso, resulting in a surface

which was subject to mold and to flaking.

Despite this, the painting has remained one of the most reproduced

works of art, countless copies being made in every medium from carpets

to cameos.

Among the works created by Leonardo in the 16th century is the small portrait known as the Mona Lisa or "la Gioconda", the laughing one. In the present era it is arguably the most famous painting in the world. Its fame rests, in particular, on the elusive smile on the woman's face, its mysterious quality brought about perhaps by the fact that the artist has subtly shadowed the corners of the mouth and eyes so that the exact nature of the smile cannot be determined. The shadowy quality for which the work is renowned came to be called "sfumato" or Leonardo's smoke. Vasari, who is generally thought to have known the painting only by repute, said that "the smile was so pleasing that it seemed divine rather than human; and those who saw it were amazed to find that it was as alive as the original".

Other characteristics found in this work are the unadorned dress, in which the eyes and hands have no competition from other details, the dramatic landscape background in which the world seems to be in a state of flux, the subdued coloring and the extremely smooth nature of the painterly technique, employing oils, but laid on much like tempera and blended on the surface so that the brushstrokes are indistinguishable. Vasari expressed the opinion that the manner of painting would make even "the most confident master ... despair and lose heart." The perfect state of preservation and the fact that there is no sign of repair or overpainting is rare in a panel painting of this date.

In the painting Virgin and Child with St. Anne

the composition again picks up the theme of figures in a landscape

which Wasserman describes as "breathtakingly beautiful" and harkens back

to the St Jerome picture with the figure set at an

oblique angle. What makes this painting unusual is that there are two

obliquely set figures superimposed. Mary is seated on the knee of her

mother, St Anne. She leans forward to restrain the Christ Child as he

plays roughly with a lamb, the sign of his own impending sacrifice.

This painting, which was copied many times, influenced Michelangelo,

Raphael and Andrea del Sarto, and through them Pontormo and Correggio. The trends in composition were adopted in particular by the Venetian painters Tintoretto and Veronese.

Leonardo was not a prolific painter, but he was a most prolific draftsman, keeping journals full of small sketches and detailed drawings recording all manner of things that took his attention. As well as the journals there exist many studies for paintings, some of which can be identified as preparatory to particular works such as The Adoration of the Magi, The Virgin of the Rocks and The Last Supper. His earliest dated drawing is a Landscape of the Arno Valley, 1473, which shows the river, the mountains, Montelupo Castle and the farmlands beyond it in great detail.

Among his famous drawings are the Vitruvian Man, a study of the proportions of the human body, the Head of an Angel, for The Virgin of the Rocks in the Louvre, a botanical study of Star of Bethlehem and a large drawing (160 × 100 cm) in black chalk on colored paper of The Virgin and Child with St. Anne and St. John the Baptist in the National Gallery, London. This drawing employs the subtle sfumato technique of shading, in the manner of the Mona Lisa. It is thought that Leonardo never made a painting from it, the closest similarity being to The Virgin and Child with St. Anne in the Louvre.

Other drawings of interest include numerous studies generally referred to as "caricatures" because, although exaggerated, they appear to be based upon observation of live models. Vasari relates that if Leonardo saw a person with an interesting face he would follow them around all day observing them. There are numerous studies of beautiful young men, often associated with Salai, with the rare and much admired facial feature, the so-called "Grecian profile". These faces are often contrasted with that of a warrior. Salai is often depicted in fancy dress costume. Leonardo is known to have designed sets for pageants with which these may be associated. Other, often meticulous, drawings show studies of drapery. A marked development in Leonardo's ability to draw drapery occurred in his early works. Another often reproduced drawing is a macabre sketch that was done by Leonardo in Florence in 1479 showing the body of Bernardo Baroncelli, hanged in connection with the murder of Giuliano, brother of Lorenzo de'Medici, in the Pazzi Conspiracy. With dispassionate integrity Leonardo has registered in neat mirror writing the colors of the robes that Baroncelli was wearing when he died.Renaissance humanism recognized no mutually exclusive polarities between the sciences and the arts, and Leonardo's studies in science and engineering are as impressive and innovative as his artistic work. These studies were recorded in 13,000 pages of notes and drawings, which fuse art and natural philosophy (the forerunner of modern science), made and maintained daily throughout Leonardo's life and travels, as he made continual observations of the world around him.

Leonardo's writings are mostly in mirror image cursive. The reason

may have been more a practical expediency than for reasons of secrecy as

is often suggested. Since Leonardo wrote with his left hand, it is

probable that it was easier for him to write from right to left.

His notes and drawings display an enormous range of interests and preoccupations, some as mundane as lists of groceries and people who owed him money and some as intriguing as designs for wings and shoes for walking on water. There are compositions for paintings, studies of details and drapery, studies of faces and emotions, of animals, babies, dissections, plant studies, rock formations, whirlpools, war machines, helicopters and architecture.

These notebooks — originally loose papers of different types and sizes, distributed by friends after his death — have found their way into major collections such as the Royal Library at Windsor Castle, the Louvre, the Biblioteca Nacional de España, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan which holds the twelve volume Codex Atlanticus, and British Library in London which has put a selection from its notebook BL Arundel MS 263 online. The Codex Leicester is the only major scientific work of Leonardo's in private hands. It is owned by Bill Gates and is displayed once a year in different cities around the world.

Leonardo's notes appear to have been intended for publication because

many of the sheets have a form and order that would facilitate this. In

many cases a single topic, for example, the heart or the human fetus,

is covered in detail in both words and pictures on a single sheet. Why they were not published within Leonardo's lifetime is unknown.

Leonardo's approach to science was an observational one: he tried to understand a phenomenon by describing and depicting it in utmost detail and did not emphasize experiments or theoretical explanation. Since he lacked formal education in Latin and mathematics, contemporary scholars mostly ignored Leonardo the scientist, although he did teach himself Latin. In the 1490s he studied mathematics under Luca Pacioli and prepared a series of drawings of regular solids in a skeletal form to be engraved as plates for Pacioli's book De Divina Proportione, published in 1509.

It appears that from the content of his journals he was planning a series of treatises to be published on a variety of subjects. A coherent treatise on anatomy was said to have been observed during a visit by Cardinal Louis 'D' Aragon's secretary in 1517. Aspects of his work on the studies of anatomy, light and the landscape were assembled for publication by his pupil Francesco Melzi and eventually published as Treatise on Painting by Leonardo da Vinci in France and Italy in 1651 and Germany in 1724, with engravings based upon drawings by the Classical painter Nicholas Poussin. According to Arasse, the treatise, which in France went into sixty two editions in fifty years, caused Leonardo to be seen as "the precursor of French academic thought on art".

A recent and exhaustive analysis of Leonardo as scientist by Frtijof Capra argues that Leonardo was a fundamentally different kind of scientist from Galileo, Newton

and other scientists who followed him. Leonardo's experimentation

followed clear scientific method approaches, and his theorising and

hypothesising integrated the arts and particularly painting; these, and

Leonardo's unique integrated, holistic views of science make him a

forerunner of modern systems theory and complexity schools of thought.

Leonardo's formal training in the anatomy of the human body began with his apprenticeship to Andrea del Verrocchio, who insisted that all his pupils learn anatomy. As an artist, he quickly became master of topographic anatomy, drawing many studies of muscles, tendons and other visible anatomical features.

As a successful artist, he was given permission to dissect human corpses at the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence and later at hospitals in Milan and Rome. From 1510 to 1511 he collaborated in his studies with the doctor Marcantonio della Torre. Leonardo made over 200 pages of drawings and many pages of notes towards a treatise on anatomy. These papers were left to his heir, Francesco Melzi, for publication, a task of overwhelming difficulty because of its scope and Leonardo's idiosyncratic writing. It was left incomplete at the time of Melzi's death more than fifty years later, with only a small amount of the material on anatomy included in Leonardo's Treatise on painting, published in France in 1632. During the time that Melzi was ordering the material into chapters for publication, they were examined by a number of anatomists and artists, including Vasari, Cellini and Albrecht Dürer who made a number of drawings from them.

Leonardo drew many studies of the human skeleton and its parts, as well as muscles and sinews. He studied the mechanical functions of the skeleton and the muscular forces that are applied to it in a manner that prefigured the modern science of biomechanics. He drew the heart and vascular system, the sex organs and other internal organs, making one of the first scientific drawings of a fetus in utero. As an artist, Leonardo closely observed and recorded the effects of age and of human emotion on the physiology, studying in particular the effects of rage. He also drew many figures who had significant facial deformities or signs of illness.

Leonardo also studied and drew the anatomy of many animals,

dissecting cows, birds, monkeys, bears, and frogs, and comparing in his

drawings their anatomical structure with that of humans. He also made a

number of studies of horses.

During his lifetime Leonardo was valued as an engineer. In a letter to Ludovico il Moro he claimed to be able to create all sorts of machines both for the protection of a city and for siege. When he fled to Venice in 1499 he found employment as an engineer and devised a system of moveable barricades to protect the city from attack. He also had a scheme for diverting the flow of the Arno River, a project on which Niccolò Machiavelli also worked. Leonardo's journals include a vast number of inventions, both practical and impractical. They include musical instruments, hydraulic pumps, reversible crank mechanisms, finned mortar shells, and a steam cannon.

In 1502, Leonardo produced a drawing of a single span 720 foot (220 m) bridge as part of a civil engineering project for Ottoman Sultan Beyazid II of Constantinople. The bridge was intended to span an inlet at the mouth of the Bosporus known as the Golden Horn. Beyazid did not pursue the project because he believed that such a construction was impossible. Leonardo's vision was resurrected in 2001 when a smaller bridge based on his design was constructed in Norway. On May 17, 2006, the Turkish government decided to construct Leonardo's bridge to span the Golden Horn.

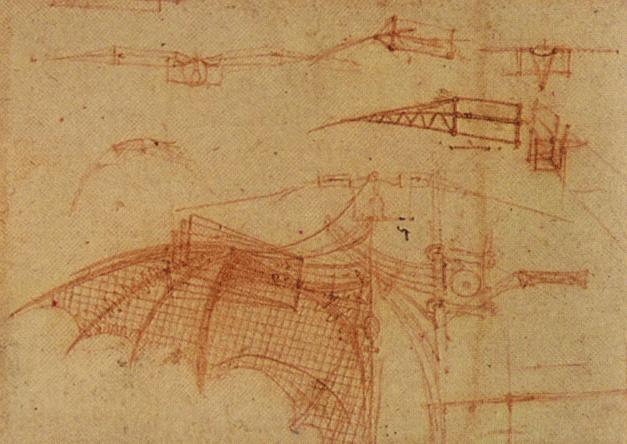

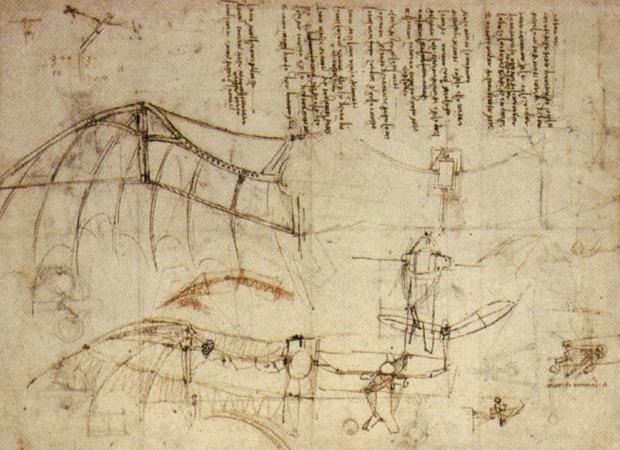

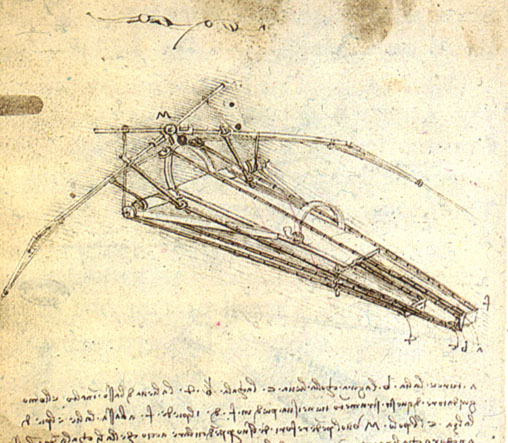

For much of his life, Leonardo was fascinated by the phenomenon of

flight, producing many studies of the flight of birds, including his

c. 1505 Codex on the Flight of Birds, as well as plans for several

flying machines, including a light hang glider and a machine resembling a helicopter. The British television station Channel Four commissioned a documentary Leonardo's Dream Machines, for broadcast in 2003. Leonardo's machines were built and tested according to his original designs. Some of those designs proved a success, whilst others fared less well when practically tested.