<Back to Index>

- Polymath Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov, 1711

- Aeronautical Engineer George Cayley, 1773

PAGE SPONSOR

Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov (Russian: Михаи́л Васи́льевич Ломоно́сов; November 19 [O.S. November 8] 1711 – April 15 [O.S. April 4] 1765) was a Russian polymath, scientist and writer, who made important contributions to literature, education and science. Among his discoveries was the atmosphere of Venus. His spheres of science were natural science, chemistry, physics, mineralogy, history, art, philology, optical devices and others. Lomonosov was also a poet, who created the basis of the modern Russian literary language.

Lomonosov was born in the village of Denisovka (later renamed Lomonosovo in his honor) in the Arkhangelsk Governorate, on an island not far from Kholmogory, in the Far North of Russia. His father, Vasily Dorofeyevich Lomonosov, was a prosperous peasant fisherman turned ship owner, who amassed a small fortune transporting goods from Arkhangelsk to Pustozyorsk, Solovki, Kola, and Lapland. Lomonosov’s mother was Vasily’s first wife, a deacon’s daughter, Elena Ivanovna Sivkova.

He remained at Denisovka until he was ten, when his father decided that he was old enough to participate in his business ventures, and Lomonosov began accompanying Vasily on trading missions.

Learning was young Lomonosov's passion, however, not business. The boy's thirst for knowledge was insatiable. Lomonosov had been taught to read as a boy by his neighbor Ivan Shubny, and he spent every spare moment with his books. He continued his studies with the village deacon, S.N. Sabelnikov, but for many years the only books he had access to were religious texts. When he was fourteen, Lomonosov was given copies of Meletius Smotrytsky's Modern Church Slavonic (a grammar book) and Leonty Magnitsky's Arithmetic.

In 1724, his father married for the third and final time. Lomonosov

and his stepmother Irina had an acrimonious relationship. Unhappy at

home and intent on obtaining a higher education, which Lomonosov could

not receive in Denisovka, he was determined to leave the village.

In 1730, at nineteen, Lomonosov joined a caravan traveling to Moscow. Not long after arriving, Lomonosov obtained admission into the Slavic Greek Latin Academy by falsely claiming to be a priest’s son. That initial falsehood would nearly get him expelled from the academy a few years later when discovered.

Lomonosov lived on three kopecks a day, living off only black bread and kvas, but he made rapid progress scholastically. After three years in Moscow he was sent to Kiev to study for one year at the Kyiv - Mohyla Academy. He quickly became dissatisfied with the education he was receiving there, and returned to Moscow several months ahead of schedule, resuming his studies there. He completed a twelve year study course in only five years, graduating at the top of his class. In 1736, Lomonosov was awarded a scholarship to Saint Petersburg State University. He plunged into his studies and was rewarded with a two year grant to study abroad at the University of Marburg, in Germany.

The University of Marburg was among Europe's most important universities in the mid 18th century due to the presence of the philosopher Christian Wolff, a prominent figure of the German Enlightenment.

Lomonosov became one of Wolff’s personal students while at Marburg.

Both philosophically and as a science administrator, this connection

would be the most influential of Lomonosov’s life.

Lomonosov quickly mastered the German language, and in addition to philosophy, seriously studied chemistry, discovered the works of 17th century English theologian and natural philosopher, Robert Boyle, and even began writing poetry. He also developed an interest in German literature. He is said to have especially admired Günther. His Ode on the Taking of Khotin from the Turks, composed in 1739, attracted a great deal of attention in Saint Petersburg.

During his residence in Germany, Lomonosov boarded with Catharina Zilch, a brewer’s widow. He fell in love with Catharina’s daughter Elisabeth Christine Zilch. They were married in June 1740. Lomonosov found it extremely difficult to maintain his growing family on the scanty and irregular allowance granted him by the Russian Academy of Science. As his circumstances became desperate, he resolved to return to Saint Petersburg.

Lomonosov returned to Russia in 1741. A year later he was named adjutant to the Russian Academy of Science in the physics department. In May 1743, Lomonosov was accused, arrested, and held under house arrest for eight months, after he supposedly insulted various people associated with the Academy. He was released and pardoned in January 1744 after apologizing to all involved.

Lomonosov was made a full member of the Academy, and named professor of chemistry, in 1745. He established the Academy's first chemistry laboratory.

Eager to improve Russia’s educational system, in 1755, Lomonosov joined

his patron Count Ivan Shuvalov in founding the Moscow State University.

In 1756, Lomonosov tried to replicate Robert Boyle's experiment of 1673. He concluded that the commonly accepted phlogiston theory was false. Anticipating the discoveries of Antoine Lavoisier, he wrote in his diary: "Today I made an experiment in hermetic glass vessels in order to determine whether the mass of metals increases from the action of pure heat. The experiments – of which I append the record in 13 pages – demonstrated that the famous Robert Boyle was deluded, for without access of air from outside the mass of the burnt metal remains the same".

He regarded heat as a form of motion, suggested the wave theory of light, contributed to the formulation of the kinetic theory of gases, and stated the idea of conservation of matter in the following words: "All changes in nature are such that inasmuch is taken from one object insomuch is added to another. So, if the amount of matter decreases in one place, it increases elsewhere. This universal law of nature embraces laws of motion as well, for an object moving others by its own force in fact imparts to another object the force it loses" (first articulated in a letter to Leonhard Euler dated 5 July 1748, rephrased and published in Lomonosov's dissertation "Reflexion on the solidity and fluidity of bodies", 1760).

In 1762, Lomonosov presented an improved design of a reflecting telescope to the Russian Academy of Sciences forum. His telescope had its primary mirror adjusted at four degrees to telescope's axis. This made the image focus at the side of the telescope tube. There the observer could view the image with an eyepiece without blocking the image. However, this invention was not published until 1827, so this type of telescope has become associated with a similar design by William Herschel, the Herschelian telescope. Lomonosov was the first person to hypothesize the existence of an atmosphere on Venus based on his observation of the transit of Venus of 1761 in a small observatory near his house in Petersburg. Lomonosov was the first person to record the freezing of mercury. Believing that nature is subject to regular and continuous evolution, he demonstrated the organic origin of soil, peat, coal, petroleum and amber. In 1745, he published a catalogue of over 3,000 minerals, and in 1760, he explained the formation of icebergs.

Lomonosov's observation of iceberg formation led into his pioneering work in geography. Lomonosov got close to the theory of continental drift, theoretically predicted the existence of Antarctica (he argued that icebergs of the South Ocean could only be formed on a dry land covered with ice), and invented sea tools which made writing and calculating directions and distances easier. In 1764, he organized an expedition (led by Admiral Vasili Chichagov) to find the Northeast Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans by sailing along the northern coast of Siberia.

Lomonosov was proud to restore the ancient art of mosaics. In 1754, in his letter to Leonard Euler, he wrote that his three years of experiments on the effects of chemistry of minerals on their colour led to him become very involved into the mosaics art. In 1763, he set up a glass factory that produced the first stained glass mosaics outside of Italy. There were forty mosaics attributed to Lomonosov, with only twenty - four surviving to the present day. Among the best is the portrait of Peter the Great and the Battle of Poltava, measuring 4.8 × 6.4 meters.

In 1755, he wrote a grammar that reformed the Russian literary

language by combining Old Church Slavonic with the vernacular tongue. To

further his literary theories, he wrote more than 20 solemn ceremonial

odes, notably the Evening Meditation on the God's Grandeur.

He applied an idiosyncratic theory to his later poems – tender subjects

needed words containing the front vowel sounds E, I, YU, whereas things

that may cause fear (like "anger", "envy", "pain" and "sorrow") needed

words with back vowel sounds O, U, Y. That was a version of what is now

called sound symbolism. Lomonosov published a history of Russia in 1760.

In addition, he unsuccessfully attempted to write an epic about Peter

the Great, to be based on the Aeneid by Vergil. In 1761, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

In 1764, Lomonosov was appointed to the position of secretary of state.

He died one year later in Saint Petersburg. Most of his accomplishments were unknown outside Russia until long after his death.

His granddaughter Sophia Konstantinova (1769 – 1844) married Russian military hero and statesman General Nikolay Raevsky. His great - granddaughter was Princess Maria (Raevskaya) Volkonskaya, the wife of the Decembrist Prince Sergei Volkonsky.

A lunar crater bears his name, as does a crater on Mars. In 1948, the underwater Lomonosov Ridge in the Arctic Ocean was named in his honor. Moscow State University was renamed ‘’M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University’’ in his honor in 1940.

The Lomonosov Gold Medal was established in 1959 and is awarded

annually by the Russian Academy of Sciences to a Russian and a foreign

scientists.

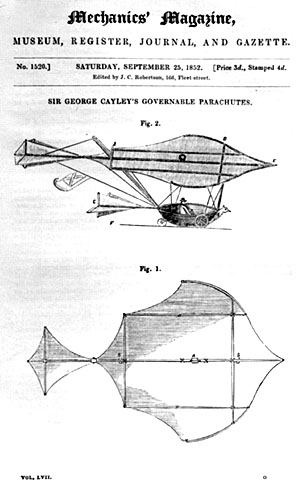

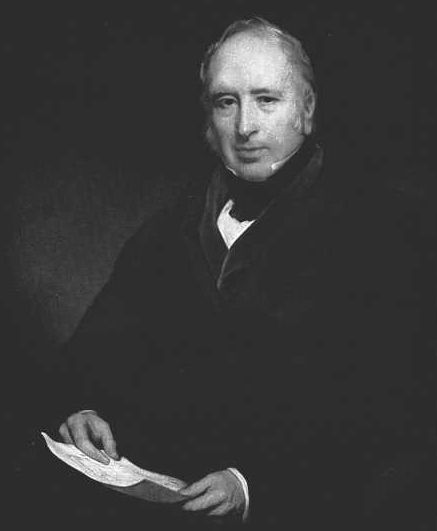

Sir George Cayley, 6th Baronet (27 December 1773 – 15 December 1857) was a prolific English engineer and one of the most important people in the history of aeronautics. Many consider him the first true scientific aerial investigator and the first person to understand the underlying principles and forces of flight. In 1799 he set forth the concept of the modern aeroplane as a fixed wing flying machine with separate systems for lift, propulsion, and control. He was a pioneer of aeronautical engineering and is sometimes referred to as "the father of Aerodynamics." Designer of the first successful glider to carry a human being aloft, he discovered and identified the four aerodynamic forces of flight: weight, lift, drag, and thrust, which act on any flying vehicle. Modern aeroplane design is based on those discoveries including cambered wings. He is credited with the first major breakthrough in heavier - than - air flight and he worked over half a century before the development of powered flight, being acknowledged by the Wright brothers. He designed the first actual model of an aeroplane and also diagrammed the elements of vertical flight. Cayley served for the Whig party as Member of Parliament for Scarborough from 1832 to 1835, and in 1838 helped found the UK's first Polytechnic Institute; the Royal Polytechnic Institution (now University of Westminster), serving as its chairman for many years. He was a founding member of the British Association for the Advancement of Science and was a distant cousin of the mathematician Arthur Cayley.

Cayley, from Brompton - by - Sawdon, near Scarborough in Yorkshire,

inherited Brompton Hall and its estates on the death of his father, the

5th baronet. Captured by the optimism of the times, he engaged in a

wide variety of engineering projects. Among the many things that he

developed are self - righting lifeboats, tension - spoke wheels, the

"Universal Railway" (his term for caterpillar tractors),

automatic signals for railway crossings, seat belts, small scale

helicopters, and a kind of prototypical internal combustion engine

fueled by gunpowder. He also contributed in the fields of prosthetics,

air engines, electricity, theater architecture, ballistics, optics and

land reclamation, and held the belief that these advancements should be

freely available.

He is mainly remembered for his pioneering studies and experiments with flying machines, including the working, piloted glider that he designed and built. He wrote a landmark three part treatise titled "On Aerial Navigation" (1809 – 1810), which was published in Nicholson's Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts. The recent (2007) discovery of cartoons in Cayley's school notebooks (held in the archive of the Royal Aeronautical Society Library in London, England) reveal that even at school Cayley was developing his ideas on the theories of flight. It has been claimed that these images indicate that Cayley modeled the principles of a lift generating inclined plane as early as 1792. To measure the drag on objects at different speeds and angles of attack, he later built a "whirling arm apparatus" — a development of earlier work in ballistics and air resistance. He also experimented with rotating wing sections of various forms in the stairwells at Brompton Hall. These scientific experiments led him to develop an efficient cambered airfoil and to identify the four vector forces that influence an aircraft: thrust, lift, drag, and gravity. He discovered the importance of the dihedral angle for lateral stability in flight, and deliberately set the centre of gravity of many of his models well below the wings for this reason; these mechanics influenced the development of hang gliders. As a result of his investigations into many other theoretical aspects of flight, many now acknowledge him as the first aeronautical engineer. His emphasis on lightness led him to shift the forces in the landing gear wheel from compression to tension by using string as wires, in effect re-inventing the wheel. This wire wheel principle was (and is) later used by others for bicycles, cars and many other vehicles.

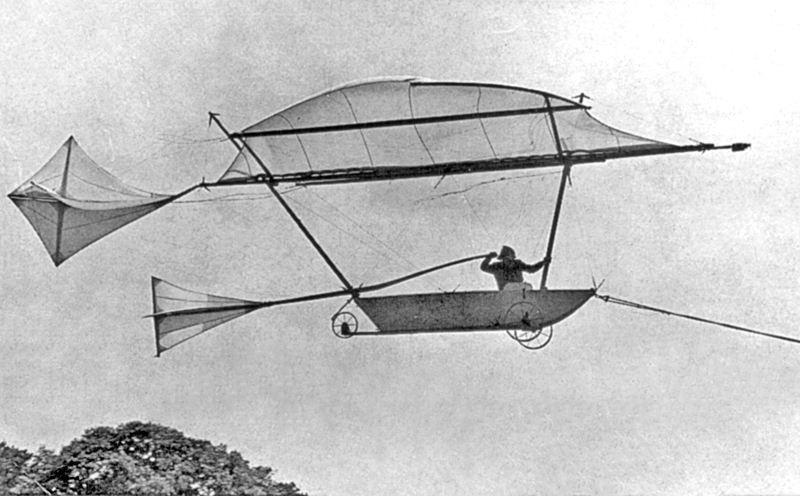

By 1804 his model gliders appeared similar to modern aircraft: a pair of large monoplane wings towards the front, with a smaller tailplane at the back comprising horizontal stabilisers and a vertical fin. Around 1843, he was the first to suggest the idea for a convertiplane, an idea which was published in a paper written that same year. During some point prior to 1849 he designed and built a biplane powered with "flappers" in which an unknown ten - year - old boy flew. Later, with the continued assistance of his grandson George John Cayley and his resident engineer Thomas Vick, he developed a larger scale glider (also probably fitted with "flappers") which flew across Brompton Dale in 1853. The first adult aviator has been claimed to be either Cayley's coachman, footman or butler: one source (Gibbs - Smith) has suggested that it was John Appleby, a Cayley employee — however there is no definitive evidence to fully identify the pilot. An obscure entry in volume IX of the 8th Encyclopædia Britannica of 1855 is the most contemporaneous account with any authority regarding the event. A 2007 biography of Cayley (Richard Dee's The Man Who Discovered Flight: George Cayley and the First Airplane) claims the first pilot was Cayley's grandson George John Cayley (1826 – 1878). Dee's book also reports the re-discovery of a series of doodles from Cayley's school exercise book which suggest that Cayley's first designs concerning a lift generating inclined plane may have been made as early as 1793.

A replica of the 1853 machine was flown at the original site in Brompton Dale by Derek Piggott in 1973 for TV and in the mid 1980s for the IMAX film On the Wing. The glider is currently on display at the Yorkshire Air Museum. Another replica, piloted by Allan McWhirter, flew in Salina, Kansas, just before Steve Fossett landed the Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer there again in March 2003, and later piloted by Richard Branson at Brompton in summer 2003.

Cayley is commemorated in Scarborough at the University of Hull, Scarborough Campus, where a hall of residence

and a teaching building are named after him. He is one of many

scientists and engineers commemorated by having a hall of residence and a

bar at Loughborough University named after him. There are display

boards and a video film at the Royal Air Force Museum London in Hendon,

honoring Cayley's achievements.